Early in the pandemic, a 28-year-old customer service representative and portrait painter caught COVID-19.

She had a high fever for a few days and trouble breathing. Her sense of smell and taste disappeared. But by mid-April 2020, she had recovered enough to start working from home.

It wasn’t until June, when she saw her family for the first time since her illness, that she realized she’d lost something else. She could no longer recognize her own father or distinguish him from her uncle.

“My dad’s voice came out of a stranger’s face,” she later told researchers.

It’s not clear how many people have developed face blindness after having COVID-19. But the woman, whom researchers identified only as “Annie” to protect her privacy, was one of more than 50 long COVID patients who reported to Dartmouth College researchers in a new study they were having trouble identifying faces after their infection.

Some people are born with face blindness, called prosopagnosia, while others lose the ability to identify faces from brain damage, typically caused by a stroke or brain injury.

Although facial recognition ability lies along a spectrum, another recent study found that more than 1% of people struggle to recognize even those they’ve met many times.

At the most extreme, some with the condition can’t even recognize themselves, apologizing for bumping into a person in the mirror. Others can’t identify familiar people if they’re in an unexpected context or wearing a hat. Some can’t follow television plot lines because the characters look too much alike.

Prosopagnosia can cause substantial social problems, said Joseph DeGutis, who led the second study and co-founded the Boston Attention and Learning Laboratory.

“When you recognize people it’s like, ‘Oh, you’re important to me,'” he said. People with face blindness unintentionally send the opposite message.

What causes long COVID? Researchers have clues about strange symptoms

‘Only beginning’: Doctors struggle to identify treatments for long COVID

What is prosopagnosia?

Six areas on each side of the brain participate in facial recognition. Damage to any one of these areas, particularly on the brain’s right side, is likely to impair facial recognition. In many cases, DeGutis said, the problem seems to be a lack of communication among the relevant areas.

About 1 in 200 people are so severely impaired they won’t recognize someone close to them, like a spouse, when they’re out of context. Roughly 2 in 100 will have mild cases, though these can worsen with age or in situations of social anxiety, said DeGutis, also an investigator at the VA Boston Healthcare Systemand an assistant professor at Harvard Medical School.

People with autism have a two- or three-fold higher chance of also having prosopagnosia compared to the general population.

Those with prosopagnosia can typically identify emotion on a face and judge the person’s gender, age and attractiveness. They just can’t seem to put the pieces together to recognize the whole.

It can be hard to identify face blindness in oneself, DeGutis said. Women seem to be more aware of their weakness than men, making up more than 70% of research volunteers, though the deficit appears equally in both sexes.

Self-awareness seems to improve in adulthood. Children and teens ages 10 to 17 were “really bad at knowing how good they were at face recognition,” DeGutis said, but adults get better in their early- to mid-20s.

Sara Axelbaum, 40, of Westchester, New York, didn’t realize she had a problem until she watched “Game of Thrones” with her husband. While he was able to keep all the characters apart, to her they were all indistinguishable bearded men.

Axelbaum’s later diagnosis explained why she had never been able to tell her mother from identical twin aunt, though others seemed to be able to make the distinction.

“I honestly had no idea that people could remember how to describe the shape of someone’s eye,” she said, referencing the time she witnessed a crime and was unable to identify the perpetrator. “I was like, ‘Wait, what?'”

Desiree Leader, now 59, grew up in a small town, so she didn’t notice how bad she was at faces until adulthood.

The first time she realized it was when she flew to Arkansas for a close friend’s wedding. The friend she was traveling with had only met the bride a few times but recognized her right away, while Leader struggled to find the bride in the crowd.

Years later when Leader joined the local Rotary club in Princeton, Massachusetts, she was expected, as the newest member, to take attendance. Panicked, she told another member about her problem, and he made a joke that maybe she had this thing he’d just read about called face blindness.

“I looked it up and I’m like, ‘Oh my God,'” she said. “I’m not stupid. I’m not self-centered.”

When was prosopagnosia recognized?

Prosopagnosia wasn’t recognized as a condition until the internet became popular in the mid-1990s. Suddenly, people began sharing this quirky deficit with others who had the same problem. Researchers got interested.

In many people, it’s also linked to other problems.

“Annie,” who developed face-blindness after COVID-19, also suddenly struggled to find the milk in her neighborhood grocery store or remember where her car was in the parking lot. She could still recognize the car but she was no longer able to form a map in her brain.

She also has common symptoms of long COVID, including fatigue, difficulty concentrating, brain fog, balance issues and frequent migraines, according to the study.

The Dartmouth researchers, Brad Duchaine and Marie-luise Kieseler,surveyed 54 others with long COVID to see if they also reported changes in facial recognition. Many did.

Similarly, those in the long COVID group self-reported new troubles navigating their environment, remembering phone numbers and tracking characters on TV shows. A few even noticed they were less able to perceive color.

Leader, who was not in the study, said she has never been able to “find my way out of a paper bag.”

She also remembers in words, not pictures.

“When I close my eyes, I don’t see anything. I didn’t realize other people do until recently,” she said. “When I read – and I love to read – I go past the description. It makes no sense to me.”

People with face blindness also develop compensatory skills. Axelbaum said she’s the one who always notices when people get a haircut or are missing an earring.

Leader could tell her friends’ identical twins apart when no one else could because she remembered which one had a freckle under one eye.

“I try to be more observant, because I have to be,” said Leader, who has since gone back to college.

How is face blindness diagnosed?

To be diagnosed with prosopagnosia requires an hours-long battery of tests and a low score on at least two. The process requires ruling out bad vision or bad memory, DeGutis said, to be sure the problem really is a lack of recognition.

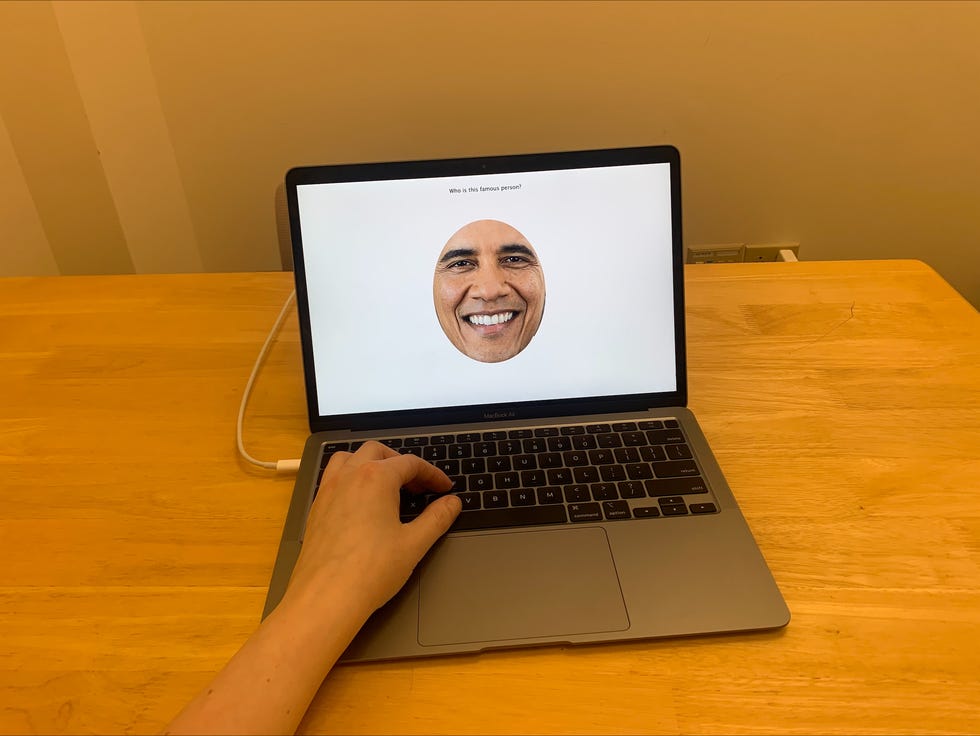

The classic diagnostic tests require learning new faces, perhaps seen in different lighting or from different angles, or identifying familiar faces, often celebrities.

In a test of celebrity faces, for instance, “Annie” correctly identified only about 30%, whereas people typically identify 84%. She also performed worse than more than 99% of the population on a test that required her to remember a new face for a short period of time.

Despite the lack of clear treatments, it remains helpful to get diagnosed, DeGutis said, because it provides insight into how poor someone is at face recognition – whether they are at the lower end of normal or truly at a disadvantage.

DeGutis said many of his patients make friends, whether consciously or unconsciously, with distinctive-looking people who are easier to recognize. “They see a 7-foot tall person at a party and say, ‘I’m going to be your friend,'” he said.

People tend to compensate for prosopagnosia by relying on others, or tricks. When she worked as a classroom assistant, Leader said she always called her students “honey,” “dear” or “sweetheart,” so she wouldn’t have to remember their names.

Axelbaum said she’s “armed” herself with people who know about her condition, so they whisper a name of a friend as they approach or introduce themselves quickly, so the other person will respond.

How is prosopagnosia treated?

It’s not that people with prosopagnosia can’t ever recognize a face, but it takes a lot more exposures for that face to become familiar, said Duchaine, a professor of psychological and brain sciences.

One man with the condition talked about being able to recognize President Bill Clinton only during his second term in office – it took more than four years to see his face enough times to stick.

It is possible to improve facial recognition with practice, DeGutis said, though it’s not a cure and it’s not easy.

Leader can now recognize the people in her rotary club, though she recently introduced herself to a friend from the Chamber of Commerce who’d come to speak at the club.

She said she doesn’t mind the embarrassment, or the fact that she has to plan around her face blindness whenever she goes out.

But she can’t stand hurting other people’s feelings.

When she was a teaching assistant, Leader once went on a ski trip with several classes from her school. While helping one boy who had broken his shoulder, she failed to recognize him as her favorite from class.

“You could see the pain on his face,” Leader said. “For me, that’s definitely the hardest part.”

Contact Karen Weintraub at kweintraub@usatoday.com.

Health and patient safety coverage at USA TODAY is made possible in part by a grant from the Masimo Foundation for Ethics, Innovation and Competition in Healthcare. The Masimo Foundation does not provide editorial input.