Sign up for notifications to the latest Insight features via the BBC Sport app and find the most recent in the series here.

Hundreds of years ago, the Native people of Alaska’s coastal whaling settlements had a unique way of communicating when a hunt had been successful.

The vast, icy plains had few hills, so it was possible to see for miles on a clear day.

Once there had been a successful catch, a messenger would run inland towards their village and, when within sight, would jump and kick both feet into the air. The village then knew it was time to jump into action and help bring the catch home.

But kicks were not always used to convey good news. One could be used to sound the alarm if someone was injured.

The passage of time and technological advances meant that these forms of long-distance communication eventually disappeared. But, once a year, the tradition is revived as a community comes together.

On 12 July 2023, thousands will flock to watch the one and two-footed high-kicks, alongside events such as the ear pull, seal hop, and Indian stick pull, in the World Eskimo-Indian Olympics (WEIO) in Fairbanks, Alaska.

WEIO was born in 1961 after two non-Native airline pilots, Bill English and Tom Richards Sr, encountered the traditional games while flying over Alaska’s outlying communities.

By then the dominant American culture had started encroaching into these communities, threatening to homogenise local customs out of existence.

“These gentlemen, who were not Native, could see where some of these traditions could be endangered,” WEIO board chairperson Gina Kalloch tells the BBC.

Native athletes and dancers from a handful of villages were brought into Fairbanks and the first WEIO took place on the banks of the Chena River. Since then it has grown, with as many as 3,000 spectators expected to flock to the Big Dipper Ice Arena this year to watch Alaska’s finest Native athletes compete.

The games all have origins in Native villages and go beyond living memory, explains Kalloch, who is of Koyukon Dena and Creole descent.

“You tell stories to pass down the history of your people and to teach lessons. You pass down the games to build and hone the skills you need to live a subsistence lifestyle, to live in a very harsh environment and be able to survive. They are survival skills,” she says.

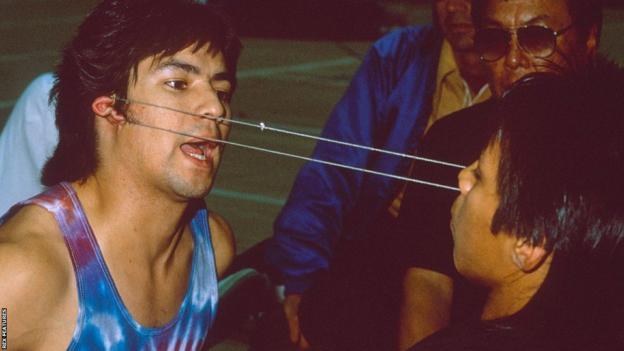

The objective of the ear pull – essentially tug-of-war with your ears – is to pull the sinew off your opponent’s ear or force them to submit. It is a game of stamina, with the winner illustrating they can withstand pain, a trait needed to survive the harsh realities of rural Alaska.

The four-man carry tests how far a single competitor can carry four volunteers draped across them. It harks back to a time when hunters had to lug their hefty catches long distances in freezing temperatures.

The Indian stick pull is a test of grip, with competitors attempting to wrench a short, greased stick from their rival. It replicates holding onto to freshly-hooked fish by the tail.

The Eskimo stick pull meanwhile involves a longer stick and relies more on strength, the same strength needed to haul a seal from a hole in the ice.

Kalloch first took part in WEIO as an impromptu competitor in the Indian stick pull in the early 1980s. She was soon winning medals in the Alaskan high kick, which requires athletes to successfully kick a suspended target while maintaining balance.

She eventually moved into coaching before becoming a member of the WEIO board.

These unique sports are growing in popularity, despite the lure of ice hockey and basketball for young people in Alaska, Kalloch says. The games have also played a powerful role in both preserving Native Alaskan culture, helping younger people reconnect with their roots and helping those recovering from substance abuse. Historically, Native Alaskans have some of the highest rates of drug and alcohol abuse in the country.

“Some of the people we worked with were at risk or recovering from battling drugs and alcohol – young people, high-school-age people. We would actively recruit them to come and learn the games,” Kalloch says.

“My fondest memories would be when we’d get someone who was at risk and barely spoke to you – didn’t really want to be there, with an attitude. Then they would discover there was something in their culture that they were good at, that they could practise, and could give them a lot of pride in themselves and their culture.”

Matthew Chagluak, 16, whose family are from the Yup’ik and Cup’ik culture, will be taking part in a wide range of events across the week.

Some of his earliest memories are with his father playing Native sports in the family home, but as he got older he focused more on basketball and wrestling. In recent years he has increasingly been drawn back to traditional games like the seal hop, partly down to the unique sense of camaraderie inherent to Native Alaskan games.

There are no age categories in WEIO – although athletes must be at least 12 years old – which means grandchildren have been known to compete alongside their grandparents. It’s common for the more experienced athletes to give technical advice to their younger rivals mid-competition.

“If we’re doing the Alaskan high kick, say it’s me and one person left and he’s on his third attempt, I would go out there and help him as much as I could so we can kick it together. It’s not so much competitive, it’s competing against yourself rather than others,” Chagluak says.

Chagluak, who now works at the Alaska Native Heritage Centre in Anchorage, says his culture has become increasingly important to him as he’s aged, and the games are a way of expressing that pride.

Miley Kakaruk, a 15-year-old Inupiaq girl, will be taking part in several WEIO categories including the Inuit stick pull, Alaskan high kick and kneel jump.

Kakaruk says travelling across Alaska to compete has led to her deepening connections within her communities.

“I have family around Alaska, but I wouldn’t have been able to know as many people if it wasn’t for these sports,” she says.

Kakaruk says she imagines her ancestors playing the same games hundreds of years ago, watched by village elders assessing who to include in their next hunting party. Each event has its own story and background in that history.

“I have learned a lot more about my culture and the origins and background of the games. Each event has a specific meaning behind it. For example, the scissor broad jump was to tell if you could jump across the ice caps.

“These games were played to help keep my ancestors in shape,” she says.

For Kalloch, this is why the preservation of Native Alaskan sport is so important.

“I think any culture across the world, if you touch base with the origins of your people and find something that speaks to you personally – that could be artistically, physically, academically – it can enrich your life to the point where you change your life,” she says.

“For indigenous people whose culture can be endangered, finding something that connects you closely to that which has been there for thousands of years, that you can personally be involved with, is an amazing gift.”