The Wall Street Journal, in its lead story, features various economists debating how how long the central bank should keep interest rates high in order to bring inflation from just over 3% to the Fed target of 2%. Most US consumers are likely to challenge the notion that inflation really is at that level, and as we’ll soon discuss, wage demands support the idea that the supposedly paramount factor of inflation expectations are higher than experts, or at least the ones the Journal consulted, believe.

Let us first point out that the Journal tacitly accepts the bad conventional wisdom that the Fed deserves credit for inflation falling from 9.1% to 3.2%. As we and others pointed out, the inflation resulted from supply constraints, particularly in key sectors like automobiles, and other Covid-related demand whipsaws, such as consumers spending what would have been vacation dollars on home improvement projects. The big accelerant of inflation was sanctions blowback, particularly increased in energy prices. Again, the Fed can’t take credit for them falling back in the US to something approaching old normal levels. From Finder:

Indeed, the central bank got a lucky break with the recent performance of the Chinese economy. Most experts assumed a fast rebound once Zero Covid restrictions ended. That would have put pressure on energy prices. But that isn’t what happened. From the New York Times last month:

China’s economy slowed markedly in the spring from earlier in the year, official numbers released on Monday showed, as exports tumbled, a real estate slump deepened and some debt-ridden local governments had to cut spending after running low on money.

The new gross domestic product data for the second quarter — from April through June — underlined what has been apparent for weeks: China’s recovery after abandoning its extensive “zero Covid” measures will be harder to achieve than Beijing and many analysts had hoped.

The sagging renminbi points to even more weakness in China. That means the Fed’s spell of good fortune on energy and potentially other commodity prices continues.

Let us not forget another wild card: the in-progress increase in Covid cases and sighting of new variants that look pretty likely to escape prior vaccinations and infection-induced immunity. If things get worse, it could dent activity in many ways, from workplace absences lowering output to the more-Covid cautious refraining from traveling and cutting back on restaurant spending. And that’s not even considering possibly more extreme action, like halts in international flight to countries deemed to have dangerous infection levels.

Another challenge to the Fed’s contribution to the moderation of price increases comes via a new article in Barron’s, which points out that the Fed’s models said the central bank would have to keep the high interest rate choke chain on much longer to wring inflation out of the economy. Since inflation moderated so much faster, if you believe those models, you’d have to concede something in addition to Fed action produced the results. From Barron’s:

When the Federal Reserve began to raise interest rates from zero in March 2022, the unemployment rate was at a near-historical low of 3.6%. The labor market had recovered almost all of its losses from the pandemic…Getting back to low and stable inflation, the story went, would require a severe recession and rising unemployment.

Fast-forward to today. Inflation is still higher than the Fed’s 2% target, but prices are rising far slower than they were a year ago….And yet the latest unemployment rate is still 3.6%, exactly the same as when the Fed’s rate hikes started…We’re seeing disinflation, but no recession; if anything, real growth is accelerating.

The recent sunny path of the economy stands in stark contrast to last year’s stormy forecasts from some of the biggest names in macroeconomics. Former Treasury Secretary Lawrence Summers predicted it would take “five years of unemployment above 5%” to contain inflation….

In a paper by economists Laurence Ball, Daniel Leigh, and Prachi Mishra presented at the high-profile Brookings Papers on Economic Activity conference last September, the authors estimated a model in which inflation was determined by labor market slack, inflation shocks, and inflation expectations. The implications of their paper for the inflation trajectory were dire. Even under highly optimistic assumptions, inflation was likely to remain high unless unemployment rose significantly or job vacancies fell.

During the conference discussion of this paper, Frederic Mishkin, a former member of the Fed’s Board of Governors, implored central bankers to not blink in the face of a recession if that’s what it would take to fight inflation. “The bottom line is that the recession is probably going to be a serious recession,” he said. Robert Gordon, an economist at Northwestern University, worried that inflation expectations would spiral out of control and the traditional relationship between job vacancies and unemployment might not return back to its prepandemic state. “Sell your stocks, folks, I think we’re in for a difficult ride,” he said.

Based on the paper, former White House Council of Economics Advisers Chair Jason Furman said it could take two years of 6.5% unemployment to return inflation to 2%.

If you had any doubts about the degree to which economists remain wedded to a 1970s picture of inflation, with rising wages producing too much demand and therefore leading to even higher wages, is sorely outdated. The nearly 50 year campaign to weaken labor bargaining power has been remarkably successful (the Barron’s article also points out flaws in the standard models). The chart below from Axios shows that workers weren’t able to demand pay increases in line with inflation, despite famed worker shortages, until very recently, and that’s due mainly to the recent sharp plunge in inflation.

Nevertheless, the debate in the Wall Street Journal centers on how hawkish the central bank should be, with some pushing for more hair-shirt wearing, others advocating for kinder treatment, and yet another cohort calling for the inflation target to be 3%. The latter is not a new idea; during the secular stagnation era, several papers argued a 4% inflation target would produce better results over time than 2%.

The Journal piece mentions the elephant in the room, how Fed action would impact Biden/Democratic party prospects in 2024. Recall that Bush the Senior attributed his 1992 election loss to Greenspan waiting 6 months longer than he should have to drop interest rates in short but pretty nasty 1991-1992 recession. My recollection is Greenspan did not deny the charge. From the Journal:

Some had concluded years ago that, because of more frequent spells in which the Fed couldn’t cut interest rates once they were lowered to zero, the 2% inflation target was too low. With a higher target of 3%, interest rates would be higher in good times, giving the Fed more scope to counteract downturns by cutting them…

“The inflation target…is not meant to be an absolute rule,” said Adam Posen, a former Bank of England policy maker who now runs the Peterson Institute for International Economics. “We should be understandably reluctant about crushing the economy to get from 3.5% to 2.25% inflation.”

A higher target is also popular among Democrats concerned that rising unemployment or a recession would threaten President Biden’s re-election prospects.

The goal of 2% inflation “is not a science. It’s a political judgment they have to make,” said Rep. Ro Khanna (D., Calif.) “I don’t see why having a particular number as the Holy Grail…is the right way to get that judgment.”

It is striking to see the Peterson Institute voting against Fed hawkishness.

But the central bank is wedded to the idea that sticking to its sacrosanct 2% target is critical to managing inflation expectations. Again from the Journal:

Central banks have used explicit inflation targets to help convince the public that inflation would remain low and stable because the banks were signaling, in advance, how they would react in periods of higher inflation.

Powell made clear he won’t consider raising the target with inflation running above it, because it risks undercutting the entire strategy. “We’re not going to be considering that under any circumstances,” he said last fall. He repeated that view to a skeptical lawmaker in March. “This is not a time at which we can start talking about changing it,” Powell said.

Richmond Fed President Tom Barkin argued that Mr. Market expects the Fed to stick to and attain its 2% goal, and setting a higher target would lead to a bond selloff. Powell and some other Fed governors reportedly believe that the current level of interest rates is already restrictive and the Fed does not need to do more unless it sees signs of accelerating activity or price increases.

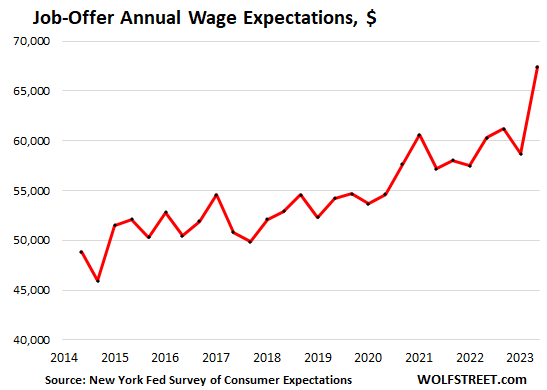

Barkin and other Fed officials believe they have reset expectations lower. Wolf Richter’s latest post argues the reverse, that workers want meaningful wage increases, markedly above the Fed’s pet level. From Wolf Richter in Powell’s Inflation Nightmare: Job Seekers, incl. the Employed, Suddenly Expect Massively Higher Wages in Job Offers:

Wages of job offers received by job seekers, and expectations for wages by job seekers surged in July…

The wages that job seekers – not just the unemployed, but also the employed looking for another job – expect to get in their job offers spiked by $7,105, or by 11.8%, from a year ago to $67,400 on average, according to the New York Fed’s Survey of Consumer Expectations (SCE) this morning. This portion of the SCE is conducted three times a year, in July, November, and March.

It was the biggest spike in job-offer wage expectations in the data of the SCE, which goes back to 2014…:

Even more important, workers on average are getting pay increases that exceed curren levels of inflation:

The average full-time wage of job offers that job seekers actually received spiked by $8,711 year over year, or by 14%, to a record $69,500 in July, according to the SCE.

The lowest wages that job seekers would be willing to accept to take a new job – the average reservation wage – jumped by 7.9% year-over-year, to $78,600.

These are massive increases in what job seekers expect, and what they were offered. And it comes amid the still unfolding scenario of unions pushing for much higher wages, and not shying away from labor action to underscore their demands. Minimum wages in states, counties, and cities that have them have also been raised, in some cases substantially.

Now this may be employers having to throw in the towel to pay more in the face of widespread workers shortages. Perhaps some establishments have hit the limit of workarounds.

But if our view is correct, that Covid, and particularly Long Covid, is a big unacknowledged driver of the employee shortage, that’s not getting any better unless and until effective Long Covid treatments are developed, tested, and launched. But there seems to be no urgency to respond, perhaps because admitting the severity of the Long Covid problem problem means also admitting how badly the officialdom has mismanaged the pandemic. Yet more and more research suggests that repeat Covid infections make Long Covid more likely.

The data on Long Covid incidence is terrible due among other things the absence of decent data on who has gotten Covid in the first place. But let’s assume the odds of getting Long Covid after a Covid infection is 10%, which is lower than the 14% odds that Science reported for Omicron. We will also charitably assume that reinfection does not increase the odds of getting Long Covid.

With those assumptions, cumulative probability says the odds of getting Long Covid after 4 infections is 35%.1 So I would bet on continued labor market tightness and more employers having to pay up for hired help. If that’s how this plays out, it’s pretty pathetic that it will have taken a lasting pandemic to shore up labor bargaining power. But the historically-minded will point out that was one of the few upsides of the Black Plague.

_____

1 Sticklers will point out that this result does not allow for what happens to people who get an active Covid case while also having Long Covid. The state of search engines plus the apparent lack of inquiry into this topic means I could not find an answer. However, I think it’s not crazy to exclude reinfection among active Long Covid cases because most sound as if they are so sick as to be largely isolated and thus at less risk of reinfection while suffering from Long Covid.