We pointed out last year during the Silicon Valley Bank and similarly-situated “too many supersized deposits” mini-panic that the bank tsuris was entirely the Fed’s creation. That bad spell of indigestion did not in and of itself point to a widespread crisis. The immediate cause (aside from inadequate supervision of deposit flight risk) was too many years of super low interest rates, which had lulled banks and investors into complacency about interest rates, followed by the worst possible action imaginable: a series of unprecedentedly fast increases in interest rates.

Despite these bad conditions, we didn’t think in and of themselves they were portents of more widespread bank industry distress. The Fed created yet another emergency liquidity scheme. But we mistakenly thought it would recognize the systemic risk of keeping rates high (by recent standards) for much longer and would back as quickly as possible out of its overly aggressive stance.1

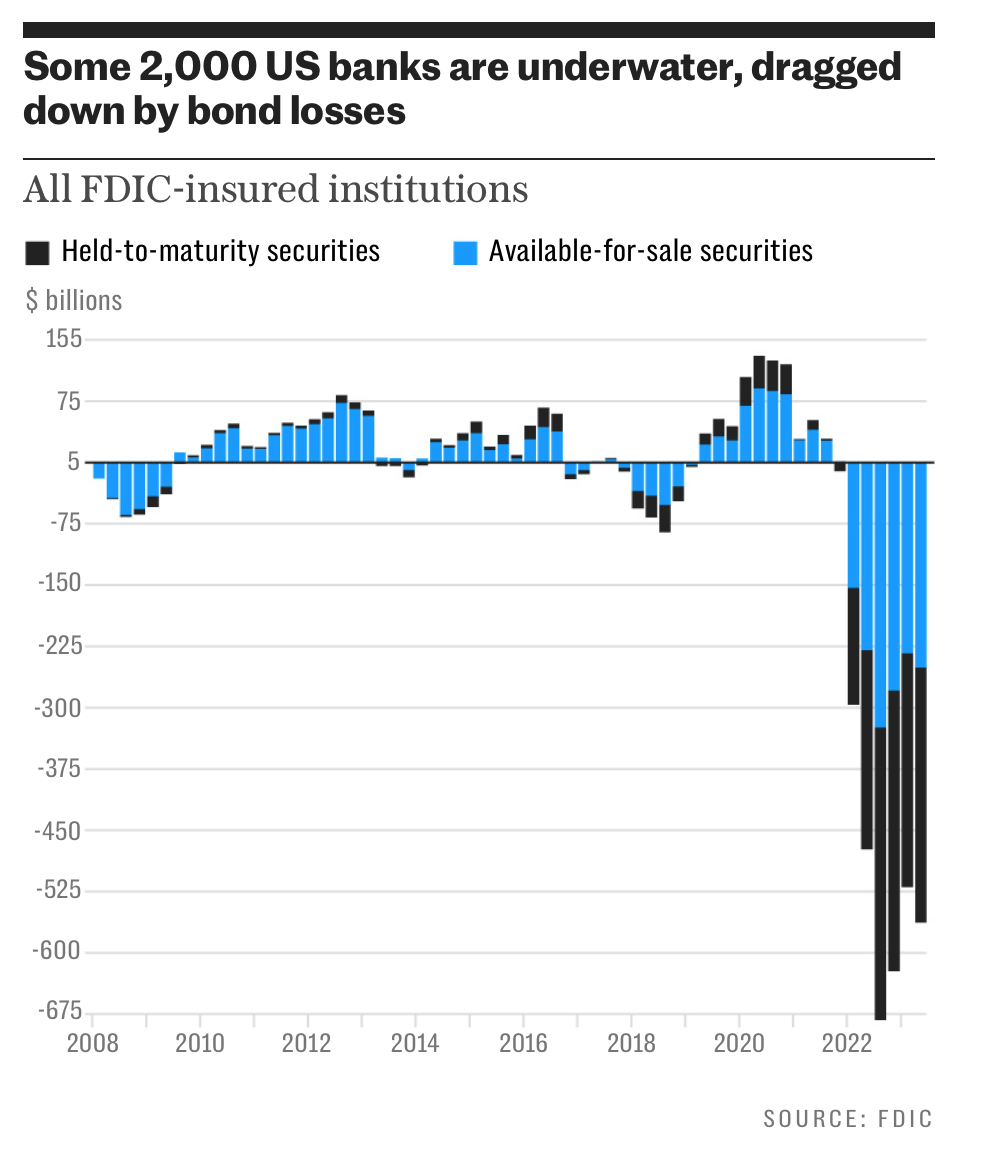

The fact that the Fed has been able to “emergency liquidity program” its way out of every major problem it created or at least could have prevented has made the Fed insensitive to the risk of blowing up banks. And so problems that could have been tamped down via corrective action a year ago are instead metastasizing. We’ll discuss two recent articles that provide supporting evidence, one a new piece at the Financial Times on expected losses at the biggest US banks, the second a much broader-scope look by Ambrose Evans-Pritchard, based on an NBER paper, on how continuing high interest rates plus too many cubicle denizens refusing to turn up at the shop every weekday is devastating the value of big city office space, particularly in less than prime buildings.

First to the Financial Times story, Largest US banks set to log sharp rise in bad loans:

Non-performing loans — debt tied to borrowers who have not made a payment in at least the past 90 days — are expected to have risen to a combined $24.4bn in the last three months of 2023 at the four largest US lenders — JPMorgan Chase, Bank of America, Wells Fargo and Citigroup, according to a Bloomberg analysts’ consensus. That is up nearly $6bn since the end of 2022…

The current level of non-performing loans is still below the $30bn peak of the pandemic. The big banks have indicated they think the rise in unpaid debts could slow soon. A number of banks cut the amount of money they put away for future bad loans, so-called provisions, in the third quarter….

More recently though, delinquencies have been rising on consumer loans, particularly credit cards and car debt. That has made some analysts nervous, especially because what the banks are putting away for loan-loss reserves now is considerably smaller than what they set aside when bad loans were rising at the start of the pandemic.

Bank stock prices are rising, which for now offers considerable protection against a widespread crisis. When financial firms become distressed, their borrowing costs shoot up, which is an immediate problem since a lot of their funding is short-tern. So increase in borrowing costs can translate very quickly into losses and in a more dire scenario, an inability to secure debt funding in needed volumes. Lenders want the sick borrower to raise more equity so they have better protection against borrower losses. But when banks are having liquidity problems, their stock prices plummet, so that raising new equity becomes catastrophically costly (assuming it can be done at all…).

The very fact that big banks cheekily are not putting away as much as they have been to cover for possible loan losses can be viewed as a sign of confidence. Lower loan loss reserves also boost current profits.

But banks and investors are essentially betting on the Fed easing off on interest rates. That is not a given. December job growth was much better than forecast, but in and of itself, that sign of economic peppiness wasn’t enough to rouse interest rate worry-warts. However, the stock jockeys are arguably underestimating the odds of Red Sea shipping disruption blowback. From Business Insider (hat tip BC):

Inflation cooled rapidly across the world last year, but it might be a touch too early for a victory lap….

Shipping companies including MSC, Maersk, and Hapag-Lloyd, as well as oil-and-gas giants such as BP, have responded to the [Houthi] attacks by diverting their vessels away from the Suez Canal, the waterway that connects Asia with Europe and the US.

That means container ships are sailing around Africa’s Cape of Good Hope, making journey times about 40% longer, according to The New York Times….

The Houthis’ attacks are already driving up big shipping companies’ costs.

Drewry’s World Container Index, which tracks global container rates, jumped 61% over the first week of 2024, with the maritime research consultancy attributing the spike to the ongoing chaos in the Red Sea…

Journeys from Singapore to Rotterdam in the Netherlands were most likely to be affected by the disruption, with freight costs jumping 115% to as much as $3,600 per forty-foot box.

As well as causing significant delays, the threat posed by the Houthis has forced shipping companies to pay more for marine insurance – and they could respond by upping their prices in a bid to pass higher costs onto consumers.

The wild card is oil. Analysts so far have not expected Houthi action in the Red Sea to have more than a $3-$4 a barrel impact on oil prices. Experts think the Houthis would not threaten the Strait of Hormuz, which would presumably make Iran unhappy as well as seriously jack up oil prices. But what if the Houthis hit a tanker and make Middle East oil much pricier via both much higher insurance costs and shipper reluctance to transit while the area was too hot for their liking?

I remember all too well in January 2007 when the subprime crisis was supposedly over and parties that should have known better tried to catch that falling safe by buying subprime servicers.

Ambrose Evans-Pritchard is more dire, as in his wont, but he also provides much more substantial analysis than the pink paper did. His recent article, Fed rate cuts come too late to avert a fresh wave of US bank failures, relies heavily on a granular analysis published by the NBER, Monetary Tightening, Commercial Real Estate Distress, and US Bank Fragility. Its authors contend that (quelle suprise!) banks have been understating the severity of their current and pretty likely losses on loans to office buildings. Lower interest rates will not bail them out of this distress by much, since it is driven by the lasting shift to work-at-home and the impossible economics of repurposing these assets. From their abstract:

We focus on commercial real estate (CRE) loans that account for about quarter of assets for an average bank and about $2.7 trillion of bank assets in the aggregate. Using loan-level data we find that after recent declines in property values following higher interest rates and adoption of hybrid working patterns about 14% of all loans and 44% of office loans appear to be in a “negative equity” where their current property values are less than the outstanding loan balances. Additionally, around one-third of all loans and the majority of office loans may encounter substantial cash flow problems and refinancing challenges. A 10% (20%) default rate on CRE loans – a range close to what one saw in the Great Recession on the lower end — would result in about $80 ($160) billion of additional bank losses. If CRE loan distress would manifest itself early in 2022 when interest rates were low, not a single bank would fail, even under our most pessimistic scenario. However, after more than $2 trillion decline in banks’ asset values following the monetary tightening of 2022, additional 231 (482) banks with aggregate assets of $1 trillion ($1.4 trillion) would have their marked to market value of assets below the face value of all their non-equity liabilities.

Ouch.

The authors depict this problem as savings & loan crisis level, not Great Financial Crisis level. However, what most choose to forget is the S&L crisis was expected to produce a much longer period of distress and slow growth than it actually did. The reason for less-than-expected damage was that Alan Greenspan succeeded in engineering a very steep yield curve, with the Fed dropping short-term rates dramatically while the yields on longer-term assets remained relatively high. That enabled the banks to earn much-higher-than-normal easy dumb profits by their classic strategy of borrowing short and lending long. They rebuilt their balances sheets comparatively quickly and were able to resume normal levels of lending.

Evens-Pritchard provides his usually fine, colorful exposition. From his account:

Emergency lending by the US federal authorities has bathed America’s struggling regional banks in short-term liquidity, disguising the slow-burn damage of the US commercial property slump…

“It’s not a liquidity problem; it’s a solvency problem,” said Professor Tomasz Piskorski, a banking specialist at Columbia University, and one of the lead authors [of the NBER paper]. “Temporary measures have calmed the market but half of all US banks are running short of deposits with assets worth less than their liabilities, and we are talking about $9 trillion,” he said.

“They are bleeding capital and could not survive if something triggers a sudden loss of confidence. It is a very fragile situation and the Federal Reserve is watching it closely”….

Property developers must refinance their debts into the most hostile lending market in living memory, while falling rents and soaring insurance costs are eroding their revenue streams. Almost $1.5 trillion comes due by the end of next year.

A Long Island developer and New York Fed board member Scott Rechler described to Evans-Prichard that the best office space, so-called Class A buildings, were still holding their value, but there was carnage in the next tier, Class B and C. He remarked: “It’s stuff that’s competitively obsolete: side-streets, dark buildings. You can’t give them away.”

Understand the implications of distress in these lower-quality buildings. A restructuring might result in a 50% loss on the loan value. And the real estate indices that most investors rely on are slow to register price declines and here are understating them more by following only the prices of Class A space.

And you can’t fix problems like this with lower interest rates or emergency facilities:

More cheery information from Evans-Pritchard:

The paper estimates that 300 banks risk “solvency runs”. The trouble may not stop there: contagion could trigger “a widespread run by uninsured depositors, unravelling a fragile equilibrium in the banking system.”

The Fed and Treasury also believed that worked could be compelled to return to work, so that office rents would return to old-normalish levels. So the regulators are likely in denial about the severity of this slow-motion but very painful unwind.

So downside risk to banks is understated. But there are still enough in the way of wild cards to have much confidence as to how things will play out.

____

1 We do not have the time today to relitigate the matter of interest rate increases being the wrong remedy for the current inflation. The Fed has become the inflation first responder, which the result of mission creep plus the Administration and Congress being derelict in their duty of managing the economy. A simple thought experiment for now: how will Fed interest rates cure the high price of eggs? Sanctions blowback? Worker shortages? Oh, ultimately the central bank can prevail by killing the economy stone cold dead….but that’s not a great idea. The failure of the Fed for decades to advocate for more countercyclical spending programs suggests it may be delighted to play an outsized role, even when it can’t perform it properly.

And as to broader Fed culpability: the central bank knew by 2014 (and contacts say even earlier) that its super low interest rate policy had become counterproductive. Yet Bernanke lost his nerve when faced with the so-called taper tantrum.