Today we will give a high-level look at part one of Jonathon Sine’s The Rise and Fall of LGFVs. Sine’s article is very detailed, yet written with an eye to holding reader interest. Here Sine succeeds by going through the history of how these vehicles, which have are the mechanism for blowing China’s real estate bubble so big and creating serious economic/investment distortions.

I hope to limit how much I recap the evolution of the LGFVs and instead focus on how they’ve created tremendous leverage in these structures, along with (in many cases) so much complexity that they would be difficult to unwind even if someone were so bold as to attempt that.

What leaps out of Sine’s account are three major destructive features of the Global Financial Crisis: Hyman Minsky-esque Ponzi finance, leverage on leverage, and complexity. This resemblance becomes more disconcerting in light of the scale of the LGFVs: their total assets are roughly 120% of Chinese GDP and their liabilities, 75%.

As disconcerting is that they’ve been growing at a markedly higher rate than overall economic growth, even at their current large size. LGFVs will eat the economy! Wellie not but they sure are trying:

Let us return to the first big alarm bell, the fact that the LGFVs are nearly all an exercise in Ponzi financing. For those of you who missed the discussion during the financial crisis years, here is a summary of economist Hyman Minsky’s theory and terminology, from a 2007 post:

Hyman Minsky, an economist who studied speculative behavior in the wake of the 1929 crash, observed that creditors become more lax about lending standards during times of stability. He divided borrowers into three types: the upstanding sort that can pay principal and interest; speculative borrowers (or “units”), who can pay interest but have to keep rolling the principal into new loans; and “Ponzi units” which can’t even cover the interest, but keep things going by selling assets and/or borrowing more and using the proceeds to pay the initial lender. Minsky’s comment:

Over a protracted period of good times, capitalist economies tend to move to a financial structure in which there is a large weight of units engaged in speculative and Ponzi finance.

What happens? As growth continues, central banks become more concerned about inflation and start to tighten monetary policy,

….speculative units will become Ponzi units and the net worth of previously Ponzi units will quickly evaporate. Consequently units with cash flow shortfalls will be forced to try to make positions by selling out positions. That is likely to lead to a collapse of asset values.

Again, keep in mind the key feature of Ponzi finance being unable to pay interest in full, and having to rely on asset sales or yet more borrowing to meet obligation. From Sine:

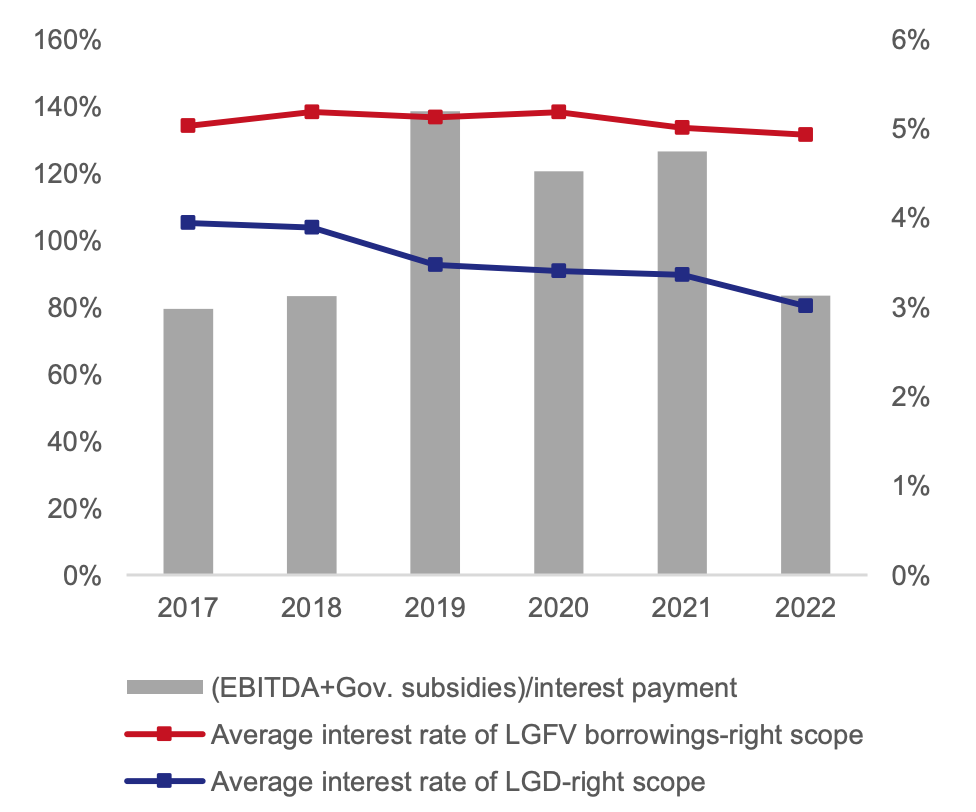

LGFV’s financial situation is, to put it frankly, very bad. In aggregate, earnings (before interest, taxes, and depreciation, i.e., EBITDA) do not cover even their interest payments. Including government subsidies only occasionally pushes the interest coverage ratio above one. Moreover, the average borrowing cost for LGFVs, 5% or so, far outpaces their 1% return on assets, posing obvious sustainability problems.

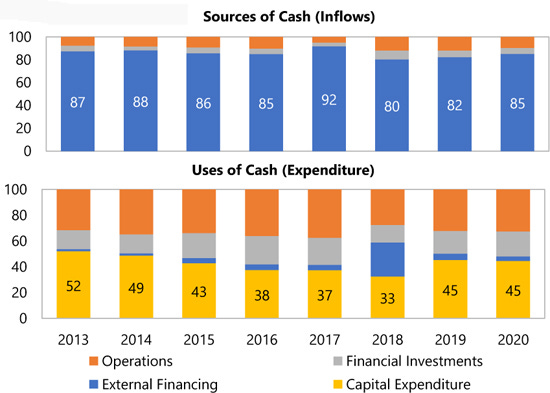

Cash flows paint an equally troubling portrait. Every year 80 to 90 percent of LGFV spending is funded by new debt. On the whole, LGFVs operating inflows do not come close to covering operating expenses. New debt is routinely added simply to make up the gap and sustain current operations.

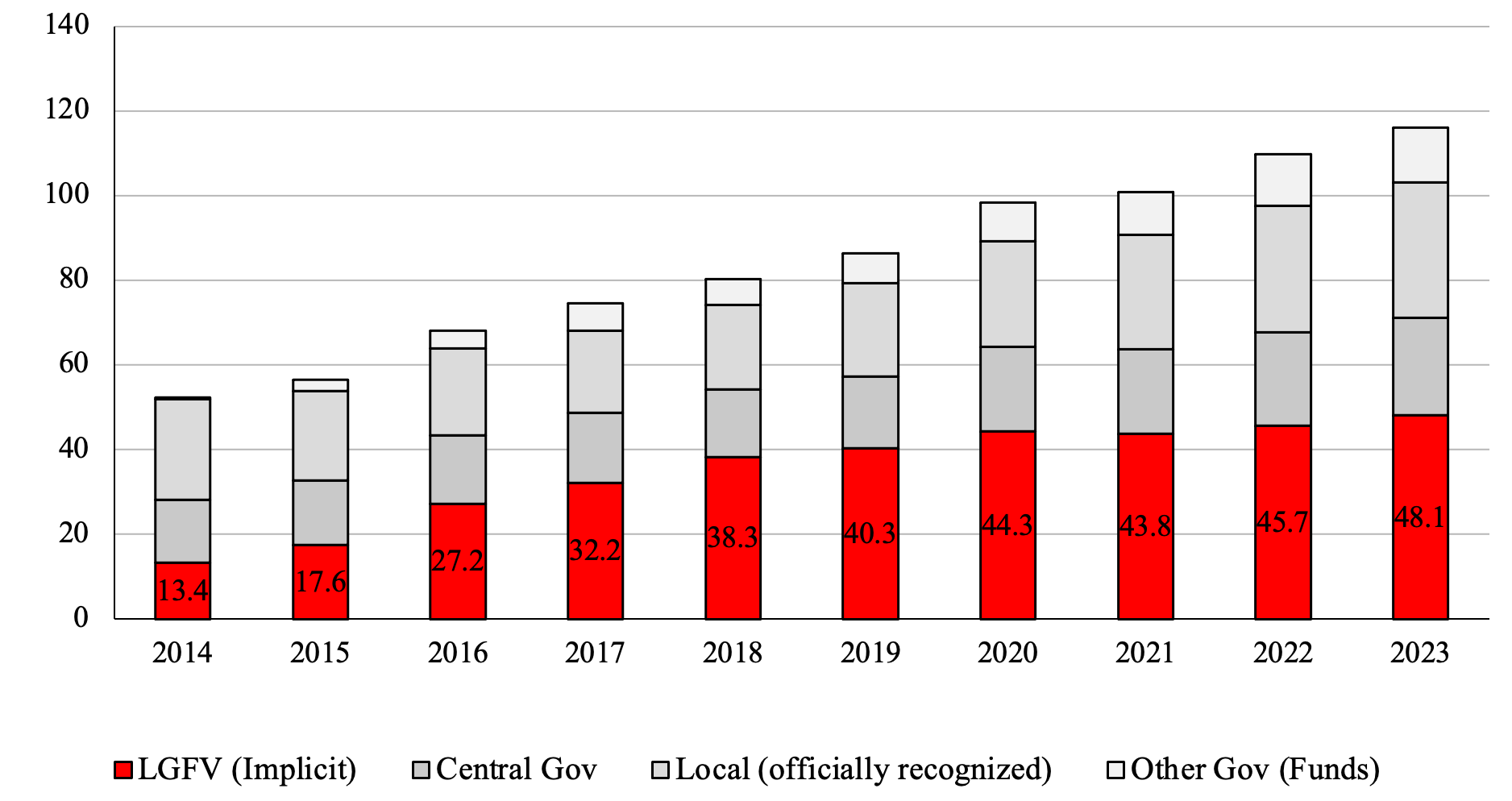

As is predictable from the above financials, the stock of interest-bearing LGFV debt has just about unceasingly expanded.4 According to statistics from the IMF, LGFV’s interest-bearing debt has grown from 13% of GDP, or RMB 8.7 trillion, in 2014 to 48% of GDP, or RMB 60.4 trillion, in 2023.

LGFV interest-bearing debt is even larger than the IMF data above suggests. An unavoidable limitation of assessing LGFVs via bottom up data, as all of the above sources do, is that it only captures the 2-3,000 LGFVs that have issued bonds and published associated financials. Another 9-10,000 smaller LGFVs have never accessed the bond market and are therefore simply missing from the data.6 A simple way of trying to estimate the rest of the interest-bearing LGFV debt is to assume LGFVs follow a Pareto distribution.7 Doing so suggests IMF estimates probably understate debt by 25%. A more reasonable, if still likely conservative, estimate of interest bearing LGFV debt is probably 60% of GDP, or RMB 75 trillion, in 2023.

We’ll skip over the first part of Sine’s in-depth history of how the LGTVs came to be. A short and highly simplified version is that Chinese government was exceptionally decentralized, which in the post-Mao, pro-market era became a problem as the role of state-owned enterprises and tax revenues shrank. Beijing, to restore its power, implemented a system in the early 1990s very much akin to Richard Nixon’s revenue sharing, but more so: the central government collected tax receipts and distributed them to local entities to spend, with the funds sometimes going through complex channels. Goods and services taxes account for about 60% of the total, with only about 6.5% from income taxes.

So the local governments got around the central government revenue constraints by creating off-budget liabilities. And the LGTV was devised by experts at the China Development Bank.

Skipping over the mechanisms the local governments used, the funding came from banks….which increasingly were newly-created, locally controlled banks. Not hard to see where this is going…

To fast forward to the global financial crisis, recall that China engaged in very large scale stimulus while the rest of the world underspent. As Sine notes:

When the center boldly announced its RMB 4 trillion stimulus plan to ward off recession, it did not intend to fund the stimulus directly but instead turned to local governments, now replete with bank licenses and financing vehicle. To this day we don’t know exactly how much China actually spent on its stimulus, though its clear the vast majority came off-budget via LGFVs….

Predictably, Beijing quickly lost what little control it had of the LGFV expansion process. Not only was the credit expansion much greater than Beijing intended, but LGFVs institutional role expanded and embedded deeper into the sinews of China’s economy.

The central government became unhappy with how the LGFVs had gotten too big for their britches, first running intrusive audits, then creating lists of shaky-looking LGFVs and pressing banks not to lend to them.

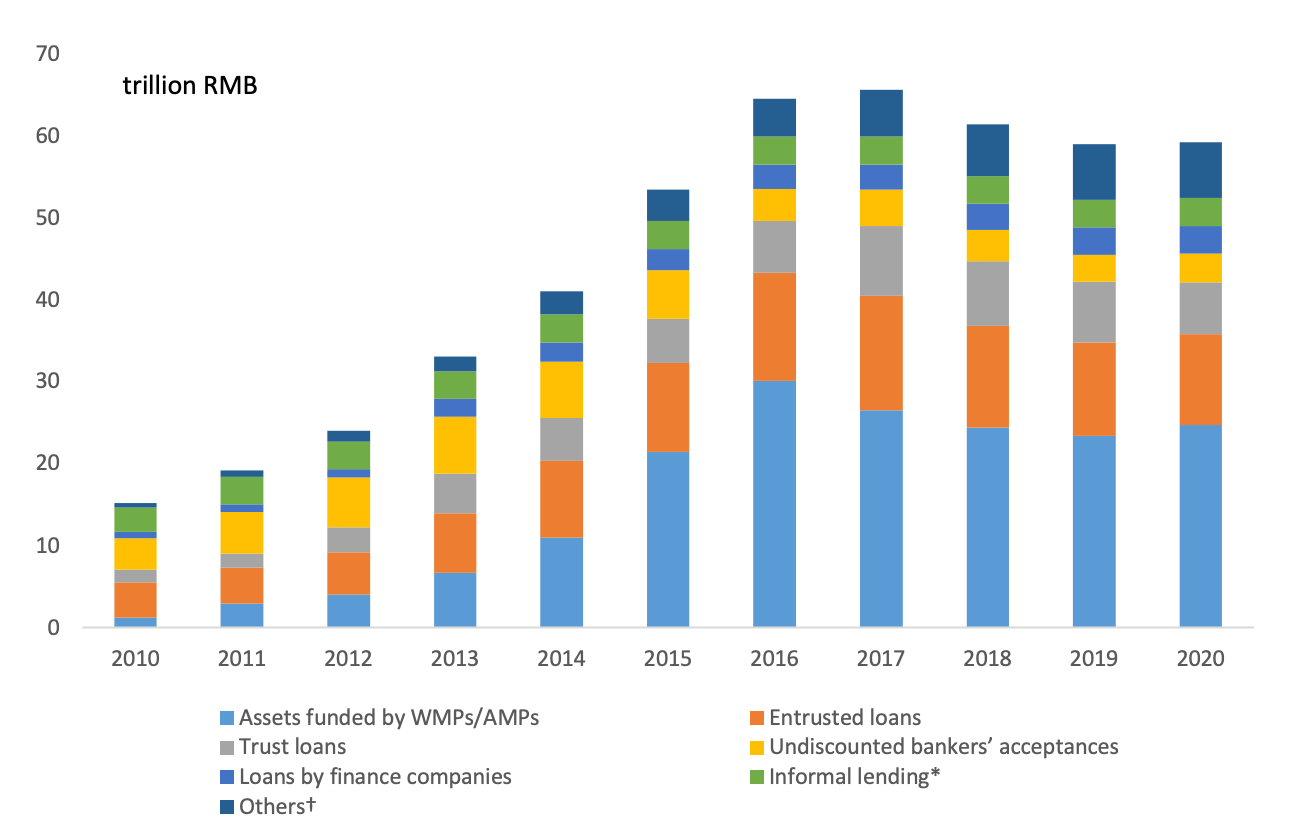

So the LGFVs found new money sources: municipal corporate bonds, which by 2018 had become 1/3 of all corporate bonds, and shadow banking.

Another echo of the crisis comes in the half-pregnant status of the corporate municipal bonds. Again from Sine:

…..most “bond buyers preferred LGFV bonds because they offered higher yields than corporate debt, but were considered government guaranteed, even though they funded projects that typically had no capacity to repay the debt.”

Remember how Fannie and Freddie debt were considered to be government guaranteed, until Freddie looking green at the gills forced the recognition that they weren’t, legally? And then Treasury put both Fannie and Freddie into conservatorship to contain market upset?

Sine points out that both the corporate municipal bonds and the shadow banking, which consists mainly of so-called wealth management products, actually do wind up back at banks, in ways that circumvent regulations:

Wealth Management Products (WMPs), or special funds set up to skirt regulations on deposit rates, are the most important shadow banking product. WMPs invested heavily in municipal corporate bonds. Chen and He et al calculate that 62% of all MCB proceeds came from WMPs. And it was banks that created those WMPs, of course with money that ultimately belongs to household depositors/lenders.

There are additional flavors of LGFV-financing regulatory arbitrage, such as entrusted loans and trust companies.

Let us now turn to a second concern, leverage on leverage. That was what set up the Roaring Twenties boom to end in the Great Crash (with trusts of trusts of trusts and CDO-like structure) and the Financial Crisis (in which, as we showed in ECONNED, CDOs created spectacular leverage). Sine provides an example:

Zunyi is relatively unremarkable, a city of middling population and economic development, firmly in the 3rd tier of China’s unofficial city ranking system. One recent development, however, has once again brought attention to the city: the increasingly urgent Party-state effort to deal with LGFV debt. Zunyi Road and Bridge Construction (遵义道桥建设) is the star of the show. A snapshot of Zunyi’s corporate structure offers hints at some of the poblems.61

Zunyi Road and Bridge, like most LGFVs, is fully-owned by the local, in this case city-level, State Asset Supervision and Administrative Commission (SASAC).62 Established in 1993 and with registered capital of RMB3.6 billion, it is the second largest of of Zunyi SASAC’s 40+ holdings, many of which also appear to be LGFVs. Zunyi Road and Bridge is itself a holding company with at least 10 companies under its umbrella. Many of these firms are also LGFVs. Its largest holdings include: Zunyi Daoqiao Agricultural Expo Park Co., Ltd., Zunyi Daoqiao Hotel Management Co., Ltd., Zunyi New District Construction Investment Group Co., Ltd., and Zheng’an County Urban and Rural Construction Investment Co., Ltd.

Zunyi Road and Bridge Holdings

Zunyi Road and Bridge holding structure, 遵义道桥建设(集团)有限公司, 股权穿透图, via 爱企查 https://aiqicha.baidu.com/company_detail_69261055076241

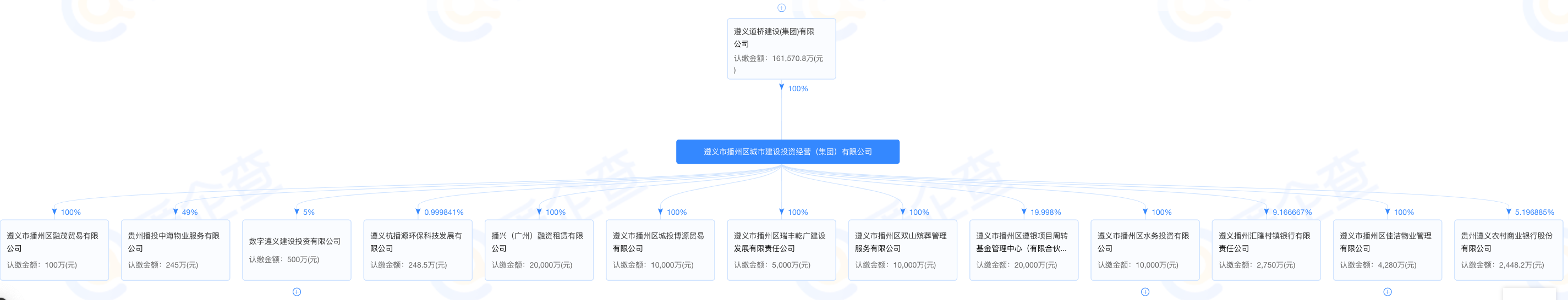

Road and Bridge’s subsidiaries also have subsidiaries. Take for example, its largest subsidiary: Zunyi City Baozhou District Urban Construction and Investment (遵义市播州区城市建设投资经营), with registered capital of RMB 1.6 billion. Baozhou Urban Construction itself fully-owns a diverse array of 10+ businesses, ranging from a funeral service company, to a financial leasing company seemingly focused on industrial equipment, to a water services management company, as well as a 49% stake in a property management company and a 5% stake in another diversified LGFV holding company.Holdings of Road and Bridge Largest Subsidiary, Baozhou Urban Construction

Zunyi City Baozhou District Urban Construction Investment Management (Group) Co. (遵义市播州区城市建设投资经营(集团)有限公司), 股权穿透图, via 爱企查 https://aiqicha.baidu.com/company_detail_62311309937102

The financing practices to go along with such a web of holdings have been similarly convoluted. One company may acquire loans or go to the bond market only to on-lend to its affiliated entities. There are hundreds, perhaps thousands, of LGFVs like Zunyi Road and Bridge and like the one in Dashan County mentioned earlier. These conglomerate LGFVs undertake what economist David Daokui Li describes as a “nested layering approach” to leverage. Companies at one level borrow funds, use that borrowed capital to secure additional loans at the next subsidiary level, and amplify debt layer by layer. All the while moving into more and more lines of business.

Needless to say, multi-entity enterprises, all lashed together with cross-ownership and debt, are well-nigh impossible to analyze accurately, let alone unwind. AIG had a similar bird’s nest of exposures in its property and casualty subsidiaries, with cross-ownership, cross-guarantees, and different fiscal year end dates too. Recall that when AIG was effectively nationalized, the plan was to sell its various entities. That never happened. The cross-exposures were a big reason why.

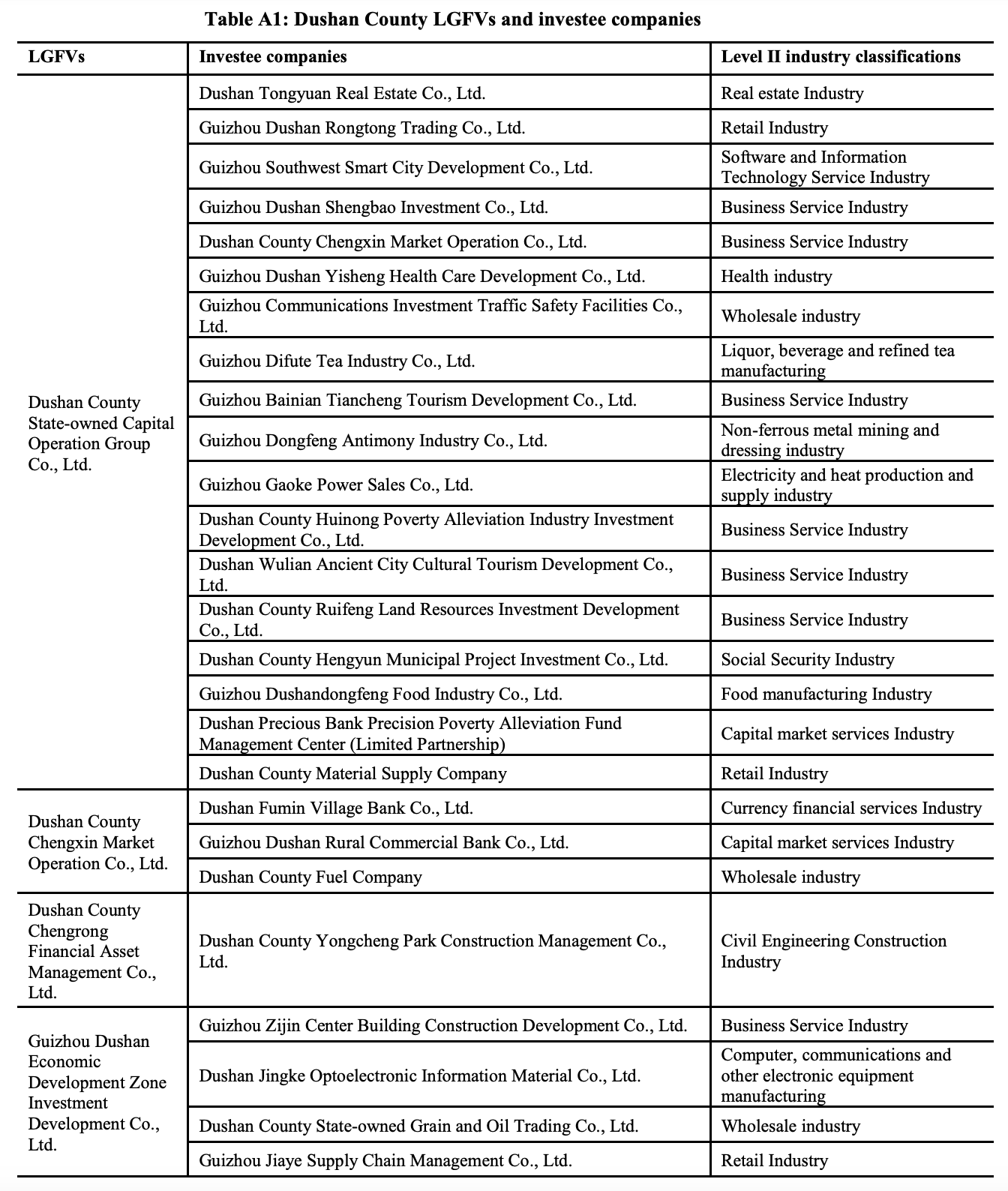

To keep the post to a manageable length, and not over-hoist from Sine, we are giving comparatively short shrift to the third worrisome sign, complexity. You can easily see the organizational and financial complexity of the Zunyi Road and Bridge entities. We have skipped over the complexity of the businesses that the LGFVs get into. An extract from a longer discussion:

As they expanded, LGFVs moved out well beyond their initial infrastructural and land development remit. One analogy is that LGFVs have become akin to twelve thousand little Huarongs. Huarong, the country’s largest asset management company, was established just a year after the first LGFV in 1999. Colloquially referred to as a “bad bank” because it was set up to take non-performing loans off the Industrial and Commercial Bank of China’s balance sheet. Initially an asset recovery firm, Huarong metastasized into a massive conglomerate with dozens of subsidiaries involved as many different industries. The crazed expansion got so crazed under former Chairman Lai Xiaomin that the CPC decided to execute him.

See this example:

Now this entire mess would seem primed for a very bad end. Yet many commentators have been predicting bad ends for China’s real estate bubble and its myriad financing mechanisms for some time, and no crisis has occurred.

However, another outcome from a big debt overhang is zombification: too much money going to refinancing what would otherwise be bad debt, at the expense of better uses.

Herbert Stein famously said, “That which can’t continue, won’t.” But he was silent on when “won’t” might come to pass.