Yves here. Keep in mind that a big reason that economists, alone among social scientists, got a seat at the policy table, was concern about the way Russia managed to industrialize within a generation, something no bourgeois/market economy had achieved. The fear was that a command and control system could indeed outproduce a free enterprise economy, hence the need for the tender stewardship of experts to make sure those Commies didn’t outdo private capital. In other words, indirectly supporting Rob Urie’s thesis, the measure of success of both systems was their productive output. Until the US went hog wild for offshoring, that meant the level and efficiency of industrialization.

By Robert Urie, author of Zen Economics, artist, and musician who publishes The Journal of Belligerent Pontification on Substack

In the US, within the context of a never-ending Cold War, ideology is put forward as the dividing line between nations and peoples. As is the case with religion, social practices that are claimed to be radically different, or even oppositional, share most of their central characteristics between them. In terms of political economy, the major ideologies of fascism, capitalism, and communism have long been claimed to be oppositional— and they often have been militarily by way of competing economic interests, as each reflected different strategies for industrializing.

American claims against Soviet economic development in the twentieth century were over the form of industrialization, not the fact of it. Like ‘science,’ the fact of industrialization has long been considered ideologically neutral, even as its particular forms were considered antithetical, even irreconcilable. However, the purpose of this piece isn’t to reconcile competing ideologies, but rather to look through to the facts which industrialization imposes. While V.I. Lenin laid imperialism at the feet of capitalism, this piece argues that industrialization sets in motion a global contest for industrial inputs, and with it, political violence.

Graph: while apples-to-apples GDP comparisons between countries can be complicated by currency fluctuations and inflation rates, this graph of China’s versus the US’s GDP (in PPP terms) is generally representative of the relationship, irrespective of these complications. After trailing US GDP for decades, China moved ahead of the US during the Great Recession. Given that ‘economic competition’ is the US’s stated rationale for war with Russia and China, the Great Recession appears to have spelled the end of American economic hegemony. Now ‘we’ get war. Source: St. Louis Federal Reserve.

The world’s best living economist, Michael Hudson, whose focus of inquiry has long been Western imperialism, has in recent years, and following from Lenin, devoted significant effort to distinguishing financial capitalism from its industrial predecessor. Supporting his thesis has been the fact that the most capitalist nation on earth, the US, has also been the most aggressively imperialistic. However, with China having now industrialized while still claiming ideological difference with the West, the global race to secure industrial inputs threatens to reignite global imperialist wars.

This isn’t to argue that China’s industrialization is in-and-of-itself motivating renewed imperial tensions. It is to argue that by way of the industrial process, competition for industrial inputs is doing so. While Americans respond with patriotic fervor to misleading nonsense about ‘freedom versus tyranny,’ industrial production provides the material basis for conflict between industrialized nations. Before age, isolation, and intellectual brittleness melted their brains, US officials clearly stated that the US motive for war with Russia was the threat that the Nord Stream LNG pipelines from Russia to Germany posed to ‘American’ interests.

To understand the conundrum from the American perspective, there is no space between the views of Joe Biden and Donald Trump regarding the US ‘right’ to seize industrial resources from sovereign nations. Mr. Trump has said so explicitly on multiple occasions. Mr. Biden defers to the Cold War canard of ‘freedom versus tyranny’ to claim a moral basis for his Hitlerian moves to light the world on fire. But the US also has a material basis for this conflict in the political control that is bought through the control of industrial inputs.

Since the mid-nineteenth century, industrialization has taken place in fits and starts around the world. Oddly (not), different ideological forms of political economy, e.g. communism, capitalism, fascism, didn’t challenge the logic of industrialization. For instance, amongst the participants in WWI, several were early to industrialize (US, Britain) and several were later to industrialize (Germany, Russia). The emergence of communism in 1917, with the Bolshevik Revolution, challenged capitalist economic organization, but not the imperative to industrialize.

That this imperative both preceded and followed WWI is hardly an accident. WWI was the first industrial war. Machine guns mowed down soldiers by the tens of thousands. Aerial bombardment facilitated the distribution of chemical and biological weapons. Monstrous machines were pitted against one another in scenes reminiscent or earlier portrayals of hell. For any nation that wanted to launch a war, or just protect itself from the imperial ambitions of others, industrialization was imperative.

Capitalist explainers tend to focus on the ‘stuff’ of industrial production, consumer goods and labor-saving devices (capital). Capitalist economists (aka ‘economists’) begin their explanations of capitalism with either imagined or real human wants (‘demand’), or sui generis economic production (‘supply’). But why would capitalists and communists both rely on the methods of industry even as they derided the competing ideological forms of social organization imagined to circumscribe it? Again, ideological difference was reflected in the form of social organization around industrialization, and not its material facts.

The Western critique of communist industrialization centered on the relative inefficiency of the communist form of industry (state direction), not on the shared imperative to industrialize. But the value of industrial output is socially determined. Capitalists long focused on creating consumer societies while the communists educated their people and provided healthcare. One can debate the merits of either vision, but both used industry as a central method to realize it.

In a broad sense, industrialization represents a path to generating certain types of wealth. Resources are gathered, and through the industrial process, are transformed into ‘wealth.’ Theories were developed to explain why certain types of wealth (‘capital’) are necessary to create other types of wealth (e.g. consumer goods). Institutional relationships were created through the industrialization process. In this way, industrial inputs aren’t ‘capitalist’ in the sense of being universally distributed. They exist in some geographic locations and not in others.

Contemporary Western economics places industrial dependencies in markets, ignoring the long history of imperialist wars to secure industrial inputs. WWI was the prime example of this tendency. Nations battled one another to control ‘wealth,’ including the industrial inputs that kept them in the fight. A later example from WWII illustrates this tendency. Japan entered WWII with an industrial economy but no secure supply of oil to keep it running. Understanding this, the Americans set up a naval blockade in the Pacific to prevent oil-laden ships from delivering oil to Japan. The Japanese faced the choice of shutting down their war machine or trying to end the naval blockade by bombing Pearl Harbor. They chose the latter.

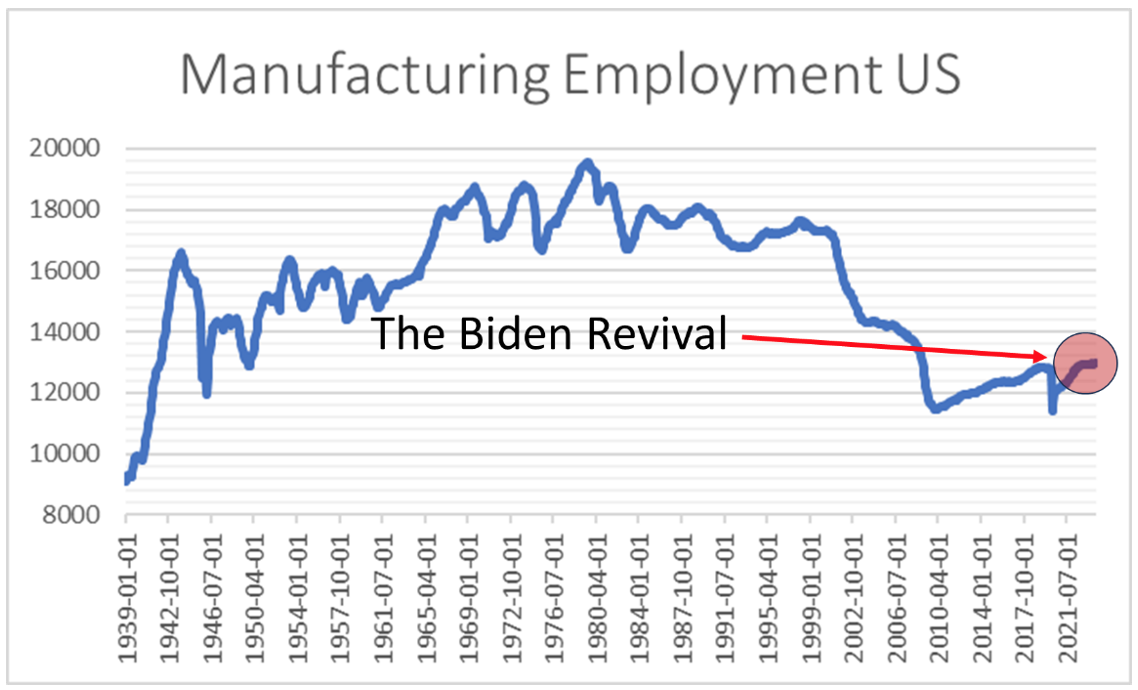

This slice of history was brought into the present when the US purposely and significantly deindustrialized over the last half century. While this isn’t evident in the dollar value of US industrial output, it is evident in what types of industrial goods are being made, and the greatly shrunken level of manufacturing employment (graph below). The US is also currently engaged in two hot wars (Ukraine, Israel), and just launched a third (by letting Israel bomb the Iranian consulate in Damascus, Syria). Irrespective of differences in their forms of social organization, Chinese, German, and American industries all need resources that they don’t control.

In theory China has a different form of political economy (‘communist’) than the US (‘capitalist’). And it certainly seems (so far) to have avoided some of the pitfalls of financial capitalism via its state-banking system. With V. I. Lenin’s claim of the relationship of late-stage capitalism to imperialism in mind, will China respond differently (than the US) to being cut out of industrial resources through Western militarism? In other words, were the US to conduct a regime change operation in a nation that Chinese industry is dependent upon for industrial inputs, will China act militarily to regain control of the needed resources?

In more generic terms, will the revival of crude capitalist imperialism by the Biden administration result in a global race by nations to 1) militarize, in order 2) to secure industrial inputs? As discussed below, Europe has little choice but to do these or perish. The US ended relative energy security for Europe when it blew up the Nord Stream pipelines. Americans who question how reliable Russian LNG (liquified natural gas) really was need to take a hard look in the mirror. The Nord Stream pipelines were destroyed without a Plan B by the Americans, the people who blew it up. Whereas the Russians 1) had a plan and 2) the infrastructure to bring it to fruition, the Americans have a ten-year time frame for securing LNG deliveries to Europe.

Graph: the Biden administration’s much- touted revival of US manufacturing has gotten manufacturing employment in the US back to where it was before the Covid-19 epidemic began in 2020. It still remains far below levels prior to 2001. Given that ‘economic competitiveness’ is the rationale for the US war against Russia in Ukraine, Mr. Biden is now in theory ‘trying’ to get back the jobs that his support for NAFTA in the early – mid 1990s, eliminated. Source: St. Louis Federal Reserve.

The base question here: is industry possible without imperialism? The decision of the US to deindustrialize, or more precisely, to outsource some industrial production, complicates assessments. As the US deindustrialized from the 1980s to the Great Recession, but particularly from the moment that China was elevated within the WTO (2001), the Americans became increasingly predisposed to a benign view of industrial competition. Now, having woken up from this imperial slumber, the US 1) lacks to ability to manufacture the weapons it will need 2) to fight the wars that it has already started.

This isn’t to overstate the case. The bipartisan George W. Bush-era war against Iraq was likely the least strategically coherent, most murderous, imperial adventure in post-WWII history. The list of nations destined for US regime change operations obtained by retired US General Wesley Clark in 2003 indicated no diminution in American blood-lust or imperial ambitions. The particular idiocy of the present is that the US gave away the industrial base that it now needs to pursue its renewed imperial ambitions.

Prior to the start of Russia’s SMO (Special Military Operation, now war) in Ukraine, developed Europe was buying LNG (liquified natural gas) from Russia at a discounted price. European industry benefitted from this arrangement because the discounted price raised profits. The arrangement ultimately gave Russia substantial political control over Europe because the withdrawal of Russian LNG would remove an instantiated source and would force European industry to pay a market price for LNG.

The destruction of the Nord Stream pipelines proceeded without the requisite planning needed to avoid an economic catastrophe for Europe. The American ‘plan,’ if it can be called that, is to spend several billion dollars over the next decade to build the infrastructure needed to deliver LNG produced by US based producers to Europe at twice or more the price that it had been paying to Russia. This price difference will render energy-intensive industries in Europe economically unviable, and slash profits for the industries that remain by the amount of the difference between the price of the ‘American’ LNG and the discounted price charged by the Russians.

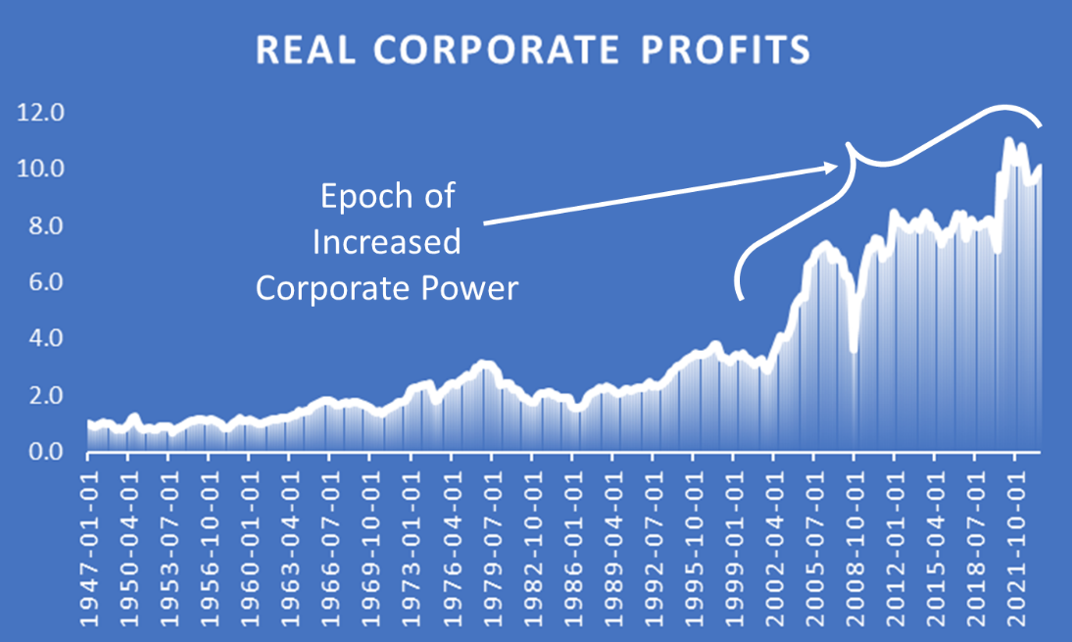

Graph: the term ‘greedflation’ is the case where corporate power has allowed corporations to unilaterally raise prices, thereby raising their profits. In capitalist economics, competition and regulation are supposed to prevent this. In fact, regulators long ago abandoned placing limits on corporate power, trusting— against history and economic logic, that ‘markets’ would prevent the accrual of market power. While the Biden administration has revived some anti-trust activity, its economic policies continue to favor economic consolidation in the hands of the oligarchs. Source; St. Louis Federal Reserve.

The question for which a satisfactory answer has yet to be given is why Europe went along with the American project in Ukraine? The ‘East versus West’ coalitions formed from it feature a cooperative East versus a vicious, petty, and tired West. The political misleaderships of Europe may be acceding to US plans to control the volume and price of energy inputs into European industry in the near-term, but doing so in the longer term will mean a severe decline for European industry. Moreover, simple geography argues against the success of the American plan. By geography alone, Russian LNG is the ‘efficient’ choice to transport.

Having jettisoned its basic industries, the US has no coherent plan to rebuild its own industrial base. The Biden administration came into office promising that its plan to build out EVs (electric vehicles) would jump start a global effort to solve mounting environmental woes. But its plan wasn’t to build EVs. The plan was to propose tax incentives for ‘green’ companies to build EVs. It was quickly determined that without building out the infrastructure needed to support the use of EVs, that few people— including auto manufacturers and electric utility executives, were on board with the build out. Rather than quickly moving to build the necessary infrastructure, the Biden administration simply backed away from its EV effort.

With the US currently engaged in two-plus wars, with no realistic way of manufacturing the weapons and materiel to fight them, and having primary responsibility for most of the environmental woes now accumulating, and no social interest in realistically addressing them, the future looks bleak. However, the West exists on the same planet as the collective East. Much like industries that lack industrial resources, producing toxic environmental effects on a shared planet is untenable in the longer term. Both suggest future geopolitical conflict.

Economist Michael Hudson, following from V.I. Lenin, has long argued that financial capitalism is a burden imposed on industrial capitalism via rent extraction and imperialism. While agreeing with Hudson on the point regarding financial capitalism, industrial capitalism produces its own burdens. Chinese officials have spent the last forty years scouring the earth to secure the inputs (resources) needed for Chinese industrial production. During this time the Americans have launched massively destructive wars in Nicaragua, El Salvador, Guatemala, Serbia, Iraq, Afghanistan, Libya, Yemen, Syria, and now Russia, Gaza, and Iran.

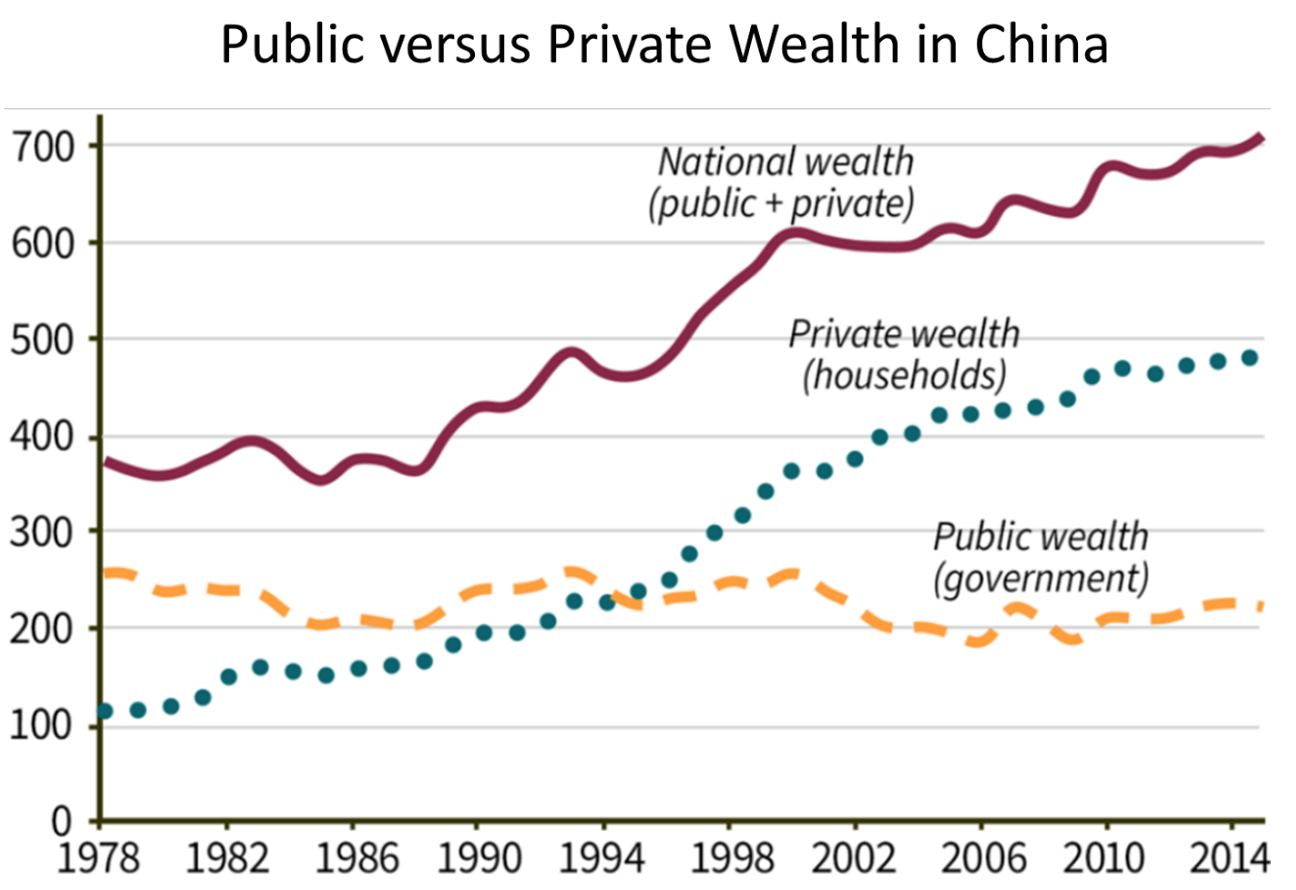

The question then is whether imperialism is idiosyncratic, or a function of industrialization and / or capitalism? Lenin’s argument depends in part on his theory of the genesis of state under capitalism. In this theory (following from Marx), the state exists to serve the interests of powerful capitalists. However, the nominally communist Chinese state promotes the interests of ‘Chinese’ industries through locating and negotiating for industrial inputs under the theory that doing so benefits the state via an integrated theory of the state (graph below).

A historical difference between this (implied) Chinese view and the view in capitalist states that private ownership and control of industry is efficient, is that the latter (US) relies on the state to launch imperial wars and squeeze international competitors using state power. For instance, blowing up the Nord Stream pipeline produced no conceivable benefit for the American people and put us in direct conflict with a nuclear armed power (Russia).

The Western ‘we’ involved in doing so is an abstraction. US state actions to support large-scale oil and gas producers (e.g. Chevron, ExxonMobil) miss that the concern isn’t reciprocal— the people who run these companies see Americans as prey, cannon fodder, and an annoyance, not fellow travelers. ‘American’ producers of LNG have destroyed aquifers across the nation with fracking waste. And the methane leaking from current and retired gas wells greatly increases US responsibility for climate change.

While American officials appear to be finally seeing some of the economic consequences of the neoliberal epoch, there appears to be little understanding of how these consequences actually came about. This is almost certainly because the same officials charged with seeing the consequences in the present didn’t anticipate them when they were proposing the policies that produced them. Additionally, class relation in the West have it that rich Westerners benefit from policies that harm the rest of us. Corporate profits rise in proportion to the environmental harms that rich Americans unload on the rest of us.

Graph: the growth of wealth in China in recent decades has largely been a function of growth in private wealth. The richest ten percent in China own nearly as much of the national wealth as in the US. A central difference is that the rich in China don’t control the Chinese government (yet), like they do in the US. Will the Chinese government stand idly by if foreign imperialists (US) threaten this private wealth through resource imperialism? And given China’s foresight in securing contracts for industrial inputs, how will it react when the US moves to take these resources (think: Iraq 2003)? Source: Stanford University.

While Wall Street may be the most powerful cheerleader for gratuitous slaughter in the world today, bringing it to heel would likely do little to reduce the imperialist impulse that is currently driving US wars abroad. In capitalist terms, financialization can be understood as a method of transferring wealth from the people that created it to its newly minted owners via economic rent extraction and financial gamesmanship. The question then: is this also the purpose of China’s state-banking system? In other words, did China’s new ownership class create the wealth that it owns, or did financial gamesmanship simply place this ownership in its hands?

As with much in life, the answers are likely 1) partially and 2) yes, respectively. As metaphor, years ago yours truly was able to get unsecured ‘inside’ funding at a rate of one-quarter of one-percent at a time when credit card borrowers were paying 19.99%. The difference was proximity to the dealer desks on Wall Street. Given that both loan types (credit cards and the inside rate) were unsecured, the risks to the lenders were similar. Absent the proximity to power, the rates should have been the same. In this sense, financial capitalism is a way to make the rich and powerful, richer and more powerful. In this example, the money saved in interest charges (19.99 – 0.25 = 19.74%) represents a transfer of wealth to the rich (I didn’t keep the difference, it was passed along).

The American rhetorical ‘pivot’ from markets to war began about when China’s GDP eclipsed that of the US during the Great Recession (top graph above). In fact, without China’s massive fiscal expansion while the US and EU were in neoliberal-inspired austerity (2010 – 2015), ‘the West’ never would have recovered. And while American wars tend to be explained in geostrategic terms, both World Wars featured races to control industrial inputs to support the burgeoning industrialization of the epoch.

Here’s the problem: given the advent of industrial warfare, any nation that doesn’t want to be invaded and controlled by other nations has no choice but to industrialize. This truth promoted both aggressive and defensive industrialization. Those bent on world domination (US, Brits, Nazis), saw industrialization as a race to control the resources that serve as industrial inputs. And the nations that can shove their environmental harms onto others most effectively see a benefit in terms of national product / profits.

The conclusion here has yet to be written. Unlike the US, China hasn’t engaged in military conquest to secure industrial inputs in modern history. Looking forward, possibly it will and possibly it won’t. There are particulars, like the US existing between two vast oceans, that may well have led its political ‘leaders’ to develop skewed assessments of the potential risks and rewards of overseas military action. And US hatred of Russia is both racist (anti-Slav) and a residual of the imperial ambitions of the American ruling class in the lead up to WWI.

The goal here isn’t to charge China, or any other nation, with actions that it has not taken. It is to argue that the circumstances that might lead it to do so are rapidly accumulating. The material basis of this conflict is the resources that serve as industrial inputs. As ‘the East’ has reacted to American imperial ambitions with Russia’s SMO, now war, against NATO in Ukraine, the US is dangerously flailing about. So, to the point made above, with little to no interest in engaging in imperialist conflagrations, will the other nations of the world respond to American imperialism abroad militarily? Would doing so make them imperialist? Is this a distinction without a difference?