By Dana Drugmand. Originally published at The New Lede

Hazardous air pollutants emitted in the manufacturing of biofuels is nearly as bad as air pollution stemming from oil refineries, and for several types of dangerous pollutants such as formaldehyde the emissions from biofuel production are far greater, a new report finds.

The assessment, which was conducted by researchers with the environmental watchdog group Environmental Integrity Project (EIP), looked at emissions generated by 275 ethanol, biodiesel and renewable diesel facilities in the United States. The researchers found that the facilities frequently violated air pollution permits while at the same time benefiting from legal exemptions and federal policy supports such as fuel-blending mandates.

As the biofuels industry continues expanding with more than 30 new facilities under construction or proposed, the industry should be seen as a threat to public health, the report warns. Stronger regulatory oversight from the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) is needed, according to EIP.

“Despite its green image, the biofuels industry releases a surprising amount of hazardous air pollution that puts local communities at risk – and this problem is exacerbated by EPA’s lax regulation” Courtney Bernhardt, EIP director of research, said in a statement.

According to the EIP report released on Wednesday, biofuels manufacturing generated 12.9 million pounds of hazardous air pollutants in 2022. That compares to 14.5 million pounds of hazardous air pollutants emitted by oil refineries that year, according to data from EPA’s Toxic Release Inventory.

(Source: Environmental Integrity Project report)

Emissions from biofuel factories were significantly higher than oil refineries for four types of hazardous pollutants – formaldehyde, acetaldehyde, acrolein, and hexane, according to the EIP report. In 2022, biofuel facilities reported releases of nearly 7.7 million pounds of hexane, over 2.1 million pounds of acetaldehyde, 235,125 pounds of formaldehyde, and 357,564 pounds of acrolein. By comparison, oil refineries that year emitted 2.6 million pounds of hexane, 10,420 pounds of acetaldehyde, 67,774 pounds of formaldehyde, and zero pounds of acrolein.

Formaldehyde is carcinogenic to humans (according to the International Agency for Research on Cancer) and acetaldehyde is a probable human carcinogen, according to EPA. Acrolein is “toxic to humans following inhalation, oral or dermal exposures” and can cause upper respiratory tract irritation, nausea, vomiting and shortness of breath, while hexane exposure can affect the central nervous system and cause irritation of the eyes and throat.

As the new report explains, these “same four pollutants also contribute to the formation of ground-level ozone, or smog, which is linked to a wide variety of respiratory ailments; as well as microscopic, soot-like particulates that can trigger heart and asthma attacks.”

The biofuels industry is the largest source of acrolein emissions in the US, and Cargill’s ethanol plant located in Blair, Nebraska is the nation’s single biggest acrolein emitter. In 2022 this facility reported releases of 34,489 pounds of the toxic pollutant, according to EIP. Researchers also found that the largest single industrial emitter of hexane in the country is the Archer-Daniels Midland (ADM) ethanol and grain processing facility located in Decatur, Illinois. The plant released 2.2 million pounds of the pollutant in 2022.

Neither ADM nor Cargill responded to a request for comment.

Geoff Cooper, CEO of the Renewable Fuels Association, took issue with the EIP report, saying it was “fundamentally flawed” in its understanding of the US renewable fuels industry, and was conflating ethanol, biodiesel and renewable diesel production. He said, for example, that hexane is not used at all in the ethanol production process anywhere in the US, yet the “falsely attributes hexane emissions to fuel ethanol.” Moreover, he said, the companies listed with the largest emissions are not ethanol plants per-se, but rather wet mills where ethanol is only one of several products. More than 90% percent of fuel ethanol is produced at dry mills, according to Cooper.

“Further, US ethanol facilities are tightly regulated on their emissions, and producers are in compliance with all federal and state emissions limits. When violations have been noted, which is very rare, producers have immediately taken corrective action and quickly moved into compliance,” he said.

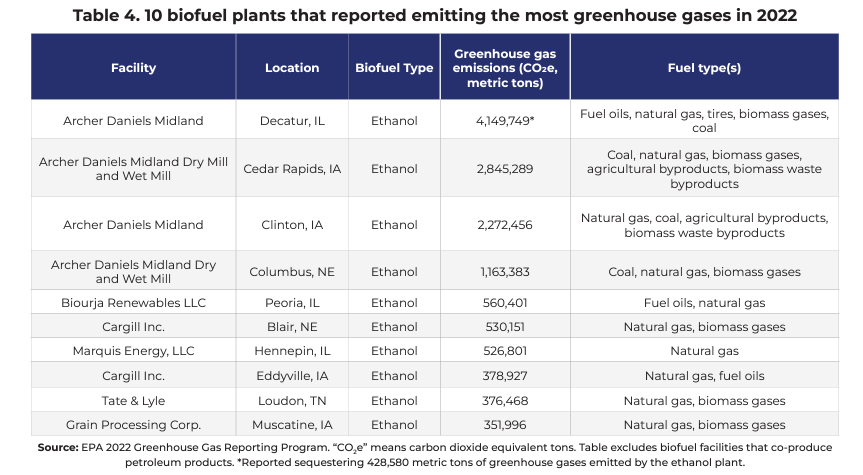

In addition to hazardous air pollutants, biofuels production generates greenhouse gas emissions that are driving dangerous climate change. US biofuels plants emitted over 33 million metric tons of this climate pollution in 2022, the report found, which is comparable to more than eight coal-fired power plants operating around the clock. “That’s a notable amount for an industry that portrays itself as climate friendly and environmentally sustainable,” Bernhardt said during a Wednesday press briefing.

Previous research has also cast doubt on the perception of these plant-based fuels as a greener alternative to petroleum. A 2022 study for example suggested that corn-based ethanol production is no less carbon-intensive, and may be even more so, than gasoline, particularly when considering the full lifecycle impacts including fertilizer consumption and land-use conversion.

(Source: Environmental Integrity Project report)

The US is the world’s largest producer of biofuels, with 18.5 billion gallons produced in 2022 alone (about 40% of the global total). The vast majority of that production, about 15 billion gallons, was ethanol, which is made primarily from corn and also from soybeans. As the report notes, almost half of all soybeans and more than a third of all corn grown goes not towards food, but rather for fuel production.

Supported by billions of dollars in government subsidies and dozens of federal policies and incentives, the US biofuels industry has grown rapidly over the last several decades. And the industry continues to expand, with at least 32 new or expanded facilities under construction or proposed that could increase production capacity 33% over 2023 levels, according to the EIP report. Much of this planned new production is for so-called “sustainable aviation fuels” made from wood or plant feedstock.

But existing biofuels facilities, the new research suggests, have a poor track record of environmental compliance and are considerable contributors to climate and hazardous air pollution that risks endangering the health of the largely rural residents living near or downwind of these factories.

The ADM plant in Illinois, one of the largest biofuels facilities in the country, was the industry’s biggest polluter in 2022, releasing 4 million metric tons of greenhouse gases and around 3 million pounds of hazardous air pollutants.

“People near Decatur, IL, are constantly exposed to air pollution that can harm their brains and cause dizziness and nausea. ADM’s ethanol plant also emits more greenhouse gases than places like oil refineries in Illinois,” said Robert Hirschfeld, director of water policy at the Prairie Rivers Network, an Illinois-based environmental organization.

Eliot Clay, land use director at the Illinois Environmental Council, contended during the press briefing that the industrial agriculture sector “continues to greenwash biofuels.” He said the new report helps expose the truth that people in central and southern Illinois “live with an alarming level of exposure to toxic industrial emissions.”

And yet, as the report explains, biofuels are exempt from more stringent air pollution controls, as the EPA in 2007 removed corn-based ethanol from the list of facilities subject to stricter pollution thresholds under the Clean Air Act. The report also found that over a third of biofuel plants (with available data) failed Clean Air Act air pollution compliance as measured through “stack tests” and that 41 percent of facilities violated their air pollution control permits at least once between July 2021 and May 2024.

In addition to better enforcement, the EIP report recommends that federal regulators end permitting exemptions for ethanol manufacturers, improve monitoring and control of hazardous air pollutants from biofuels facilities, require that producers enhance the accuracy of their emissions reporting, and calls for an end to biofuels subsidies and mandates such as the Renewable Fuel Standard.

“The environmental benefits of these government supports are questionable at best,” Bernhardt said.