By Lambert Strether of Corrente.

The balance between the length of this post and the reseach done to write it turned out to be a little off, but hopefully readers will find it useful in any case. I will cover the following topics, mostly by trusting the literature I have been able to curate: The history of the two Mpox outbreaks, Mpox wastewater readings in the United States (some cause for optimism), Mpox R0 (contagiousness), and whether Mpox is airborne (it is, although the usual suspects along the Covid minimizers and some in our lazy and credulous press are denying it). Here goes:

The History of Mpox

On the 2003, 2022 and 2023 outbreaks, from The Royal Society (PDF), “Quantifying the basic reproduction number and underestimated fraction of Mpox cases worldwide at the onset of the outbreak“:

The mpox (formerly known as monkeypox) is a viral zoonotic disease caused by an orthopoxviral infectious agent (known as mpox virus, MPV) that results in a smallpox-like disease in humans and some other animals and is recognized as the most critical orthopoxviral infection after the eradication of smallpox. It is endemic in Western and Central Africa, and cases outside of Africa have emerged only in recent years, including the 2003 outbreak in the United States in which all infections were related to contacts with infected animals. During the 2022 outbreak, mpox disproportionately impacted the community of men who have sex with men (MSM), which is a term that refers to a subset of individuals defined by their sexual behaviour rather than their sexual orientation or identity. This term was coined by prominent epidemiologists and is primarily used in public health contexts to address sexual health issues and risks without specifically labelling the sexual orientation of these individuals. The MSM community is incredibly diverse and may include gay and bisexual men (known as gbMSM), as well as men who do not identify as gay or bisexual but who still engage in sexual acts with other men (known as heterosexually identified MSM or hMSM). While there may be overlap, the MSM category is distinct from the broader 2SLGBTQIAP+community, which includes people of diverse sexual orientations and gender identities, encompassing lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer or questioning, intersex, asexual, pansexual and Two-Spirit individuals, focusing more on identity rather than specific sexual behaviours.

The first mpox cases were confirmed in early April–May 2022 in the United Kingdom, subsequently spreading to several countries on almost all continents, according to the World Health Organization (WHO) and the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) data. However, it seems that cases were already spreading in Europe much earlier. Since then, mpox cases around the globe have increased at a rapid rate. However, at the beginning of the 2022 mpox epidemic, the scale of the outbreak in several countries, including the United States, was bigger than what the CDC and WHO data showed, probably owing to the ineffectiveness of the testing system (testing was limited and slow), as well as to individuals’ willingness to get tested and report their results.

(See here for the story of Nigeria’s Bolaji Otike-Odibi, instrumental in bringing the 2022 Mpox outbreak to the world’s attention.) Here is detail on the 2024 outbreak, a different and more virulent clade (approximate with “variant) which has moved beyond the MSM category and the 2SLGBTQIAP+[1] community and infected children. From Nature, “Sustained human outbreak of a new MPXV clade I lineage in eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo“:

In September 2023, the first-ever mpox cases were detected in Kamituga Health Zone, a densely populated mining area in South Kivu Province in eastern DRC. Initial sequencing of six cases from January 2024 by Masirika et al.12,13 revealed the presence of a divergent lineage of clade I. In this Brief Communication, we describe the results of an investigation into this outbreak, including detailed genomic analysis of cases dating back to September 2023, to elucidate the origins and nature of this event.

Among individuals with PCR-confirmed mpox, the majority were female (56/108, 51.9%) and the median age was 22 years (interquartile range 18–27) (Fig. 1b). Children <15 years constituted 14.8% (16/108) of confirmed cases, individuals aged 15–30 years accounted for 67% (73/108), and 17.6% (19/108) of cases were individuals 30–49 years. Additionally, 28.7% (31/108) of the confirmed cases and 29.5% (71/241) of all suspected cases indicated sex work as their profession during the survey conducted by the provisional health authorities (Methods). None among individuals with confirmed mpox had been vaccinated against smallpox, which was eliminated in the DRC in 1971 with vaccination campaigns ending in 1980 (ref. 14).

Note the halting of smallpox vaccination as the efficient cause for Mpox). More:

The sustained spread of clade I MPXV in Kamituga, a densely populated, poor mining region, raises important concerns. The local healthcare infrastructure is ill-equipped to handle a large-scale epidemic, compounded by limited access to external aid. The 241 reported cases are probably an underestimate of the true incidence of mpox cases occurring in the area. In conversations with local healthcare workers, they reported that many additional people in the community had mpox symptoms but did not seek care.

Frequent travel occurs between Kamituga and the nearby city of Bukavu, with subsequent movement to neighboring countries such as Rwanda and Burundi. Moreover, sex workers operating in Kamituga represent several nationalities and frequently return to their countries of origin. Although there is no current evidence of wider dissemination of the outbreak, the highly mobile nature of this mining population poses a substantial risk of escalation beyond the current area and across borders. The international spread of clade I MPXV is particularly concerning due to its higher virulence compared to clade II.

(The recent Swedish case was Clade 1.) As a result, from Vox, “Mpox never stopped spreading in Africa. Now it’s an international public health emergency. Again“:

The new international spread of mpox clade I is spurring concerns that a deadlier mpox pandemic might be on the horizon and triggered the Africa Centres for Disease Control and Prevention and the World Health Organization to designate the ongoing mpox outbreaks as health emergencies.

Africa CDC is the public health agency of the African Union, which represents 55 African states. It is the first time the agency has designated any outbreak a continental emergency. Other African countries are also facing resurging mpox outbreaks caused by the clade II virus. In May, there were a total of 465 mpox cases documented across all African countries and in June there were 567, a 22 percent increase.

“We declare today this public health emergency of continental security to mobilize our institutions, our collective will, and our resources to act swiftly and decisively,” said Africa CDC Director General Jean Kaseya in a press briefing Tuesday.

Outbreak response efforts in the DRC and other African countries have once again been hamstrung by the same challenges health officials faced during previous outbreaks and pandemics, including Covid: a lack of global solidarity and an unwillingness to share life-saving resources. While vaccine doses were rapidly disseminated in the US and Europe in 2022, vaccines are only now starting to trickle into the DRC. But even so, only a couple hundred thousand vaccines will be available for a population of more than 100 million people.

Slowly, national governments and multinational organizations such as the African Union are working to improve domestic public health infrastructure and technical capacity and to reduce dependency on donor countries. While Africa CDC’s unprecedented move to designate the mpox outbreaks a regional health emergency signals a continuation of these efforts, it is unclear if the designation will help spur the rapid influx of resources needed to respond to the mpox outbreaks.

But we’ll certainly buy up the gold from “artisanal miners” in Kamituga!

Mpox Wastewater Readings in the United States (So Far)

Here is the CDC’s Mpox Wastewater map:

Actually encouraging. I do wish that detecting Mpox was part of CDC’s traveller’s program, as with Covid.

Mpox R0

Here is a 2023 R0 calculation from the 2022 outbreak, from the Journal of Medical Virology, “Monkeypox: Early estimation of basic reproduction number R0 in Europe“:

Starting from our new surveillance system EpiMPX open data, we defined an early R0 measure, using European ECDC confirmed cases from the epidemic start to the end of August 2022; our early R0 pooled median is 2.44, with high variability between countries. We observed the higher R0 in Portugal and Germany, followed by Italy, Spain, and France. Anyway, these high estimates refer to the MSM group rather than to the general population.

MSM = Men who have Sex with Men.

Here is a second 2024 R0 calculation, also from the 2022 outbreak, again from The Royal Society (PDF). They built a model that includes the fact that sexual transmission of Mpox (MSM, prositution) leads to under-reporting. The result:

Estimated R0 ranged between 1.37 (Canada) and 3.68 (Germany).

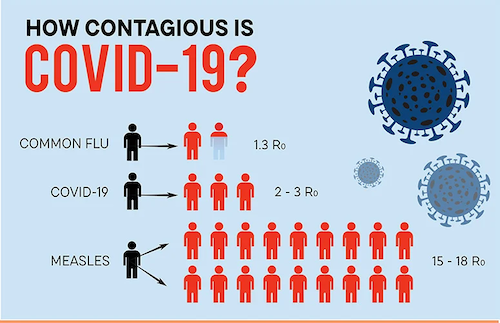

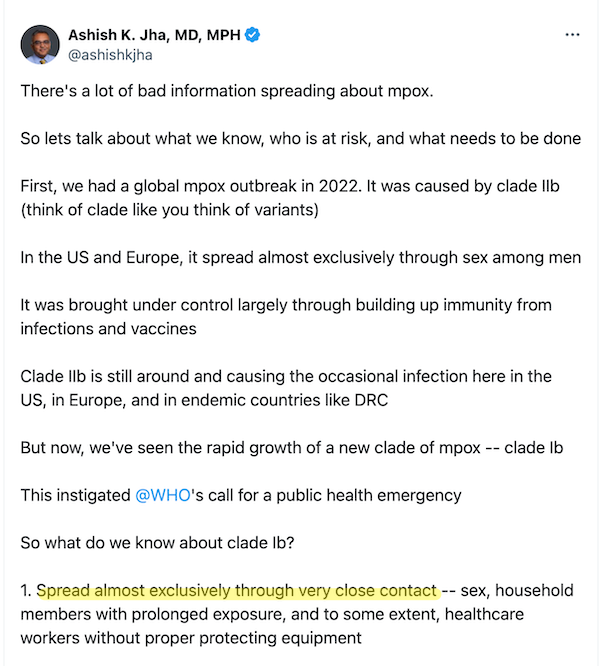

For reference, here is R0 for the flu, Covid-19, and the measles:

Caveats from Harvard Global Health Institute: “R0 values can be helpful in gauging outbreak severity, but a high R0 value does not guarantee a world-wide spread, or a pandemic. It is a calculation of an average value that is based on estimates of averages. When early R0 values are produced, they should be circulated with care and guidance on how to interpret them.” And CDC: “R0 is rarely measured directly, and modeled R0 values are dependent on model structures and assumptions. Some R0 values reported in the scientific literature are likely obsolete. R0 must be estimated, reported, and applied with great caution because this basic metric is far from simple.”

Is Mpox Airborne?

First, let me fire off a salvo of quotes from the Lancet, which has been all over this since 2022. You will notice that the answer to “Is Mpox Airborne?” shifts from “Needs more research,” to “possibly,” to “yes” over time. Neither I nor any of the authors claim that Mpox is exclusively transmitted “through the air”; there are several modes of transmission, including touching the lesions.

The Lancet (August 2022), “Clinical features and management of human monkeypox: a retrospective observational study in the UK“:

Several of the patients experienced prolonged viraemia and upper respiratory tract viral shedding after crusting of all cutaneous lesions, leading to extended isolation in hospital.

The infection control implications of upper respiratory tract viral shedding should be considered in future outbreaks.

The Lancet (December 2022), “Air and surface sampling for monkeypox virus in a UK hospital: an observational study“:

Three (75%) of four air samples collected before and during a bedding change in one patient’s room were positive (Ct 32·7–36·2). Replication-competent virus was identified in two (50%) of four samples selected for viral isolation, including from air samples collected during bedding change. These data show contamination in isolation facilities and potential for suspension of monkeypox virus into the air during specific activities.

IOW, as we might say, “airborne fomites” (from particles in the bedding). This is how many HCWs concepualize and limit airborne transmission, similarly to Aerosol Generating Procedures, limited to specific places like surgical theatres or dentist’s offices, and not moving like smoke through the entire facility.

The Lancet (April 2023), “Mpox respiratory transmission: the state of the evidence“:

The relative contribution of the respiratory route to transmission of mpox (formerly known as monkeypox) is unclear. We review the evidence for respiratory transmission of monkeypox virus (MPXV), examining key works from animal models, human outbreaks and case reports, and environmental studies. Laboratory experiments have initiated MPXV infection in animals via respiratory routes. Some animal-to-animal respiratory transmission has been shown in controlled studies, and environmental sampling studies have detected airborne MPXV. Reports from real-life outbreaks demonstrate that transmission is associated with close contact, and although it is difficult to infer the route of MPXV acquisition in individual case reports, so far respiratory transmission has not been specifically implicated. Based on the available evidence, the likelihood of human-to-human MPXV respiratory transmission appears to be low; however, studies should continue to assess this possibility.

(“Close contact” should be banned as a term of art, since it conflates fomite transmission (touch) with airborne transmission (breathing, talking). Both are “close.”)

The Lancet (January 2023, not cited in the article above), “Monitoring monkeypox virus in saliva and air samples in Spain: a cross-sectional study“:

We did a cross-sectional study in patients with monkeypox confirmed by PCR who attended two health centres in Madrid, Spain. For each patient, we collected samples of saliva, exhaled droplets within a mask, and aerosols captured by air filtration through newly developed nanofiber filters. We evaluated the presence of monkeypox virus in the samples by viral DNA detection by quantitative PCR (qPCR) and isolation of infectious viruses in cell cultures.

The identification of high viable monkeypox virus loads in saliva in most patients with monkeypox and the finding of monkeypox virus DNA in droplets and aerosols warrants further epidemiological studies to evaluate the potential relevance of the respiratory route of infection in the 2022 monkeypox virus outbreak.

The Lancet (June 2023), “MPXV and SARS-CoV-2 in the air of nightclubs in Spain.” I implore to erase the term “sex room” from your mind, and conceptualize this study as a typical case of a 3Cs space: Closed, crowded, close contact:

We monitored SARS-CoV-2 and MPXV genomes in the air in six bar areas and one dark room (sex room) in Madrid nightclubs frequently visited by MSM during four weekend days in 2022 (July 8, July 16, Aug 8, and Nov 5). To sample aerosols, air samples were collected in nanofibre filters3 located behind the club bar or in a central location of the dark room away from customers (>2 m distance), and viral genomes were detected by quantitative PCR (appendix p 2).

All air samples from July were positive for SARS-CoV-2, with 12 (86%) of 14 samples containing more than 50 genomes per m3, and three samples even reaching more than 1000 genomes per m3 (appendix pp 4, 5). These findings were consistent with epidemiological data that showed a high prevalence of COVID-19 among people older than 60 years in Spain at the time. All except one of the air samples from August and November were negative for SARS-CoV-2. On July 8, which coincided with the gay pride parade in Madrid, MPXV DNA was undetectable in the air, with the exception of one sample, and on July 16, it was detected in two samples. MPXV in the air had increased considerably on Aug 8, with four (57%) of seven positive samples containing more than 100 genomes per m3, or even more than 1000 genomes per m3 in one case; this date coincided with the peak incidence of mpox in Spain. High viral loads in the air were detected in the dark room but also in bar areas, sometimes even at higher concentrations. MPXV was undetectable in November. Carbon dioxide concentrations were very high in all nightclubs, indicating poor ventilation and a high risk of airborne transmission (appendix p 5).

To our knowledge, this is the first evidence of airborne SARS-CoV-2 and MPXV in nightclubs. Aerial virus monitoring corresponded with epidemiological incidence, indicating that it is a reliable tool to evaluate environmental risks of infection. MPXV was previously detected in the air of health centre consulting rooms, and we showed high virus levels in the air of indoor public spaces, presumably exhaled from people who were infected with MPXV. This finding suggests that MPXV exposure occurs beyond skin or sexual contact, and future studies to address airborne monkeypox virus transmission are warranted. If COVID-19 or mpox cases rise in the future, people attending mass events or indoor public entertainment venues should be made aware of the risk of airborne exposure to these viruses.

I believe in the precautionary principle, so this is enough for me to answer “Yes, it’s airborne,” even though no contact tracing was done.

The Lancet (May 2023, citing to the above, and summarizing others), “Airborne transmission of MPXV and its aerosol dynamics under different viral load conditions“:

The estimated minimum sizes of respiratory particles carrying MPXV, based on reported viral loads in respiratory fluids, are sufficiently small to generate viral aerosols.

This analysis based on aerosol dynamics with viral load data is in harmony with two sets of experimental findings in The Lancet Microbe. Susan Gould and colleagues3 detected infectious MPXV in air samples collected during a bedding change for patients in a UK hospital. The authors also detected MPXV DNA in air samples collected at distances of more than 1·5 m from the beds of patients.3 Furthermore, Hernaez and colleagues4 reported that from 40 to about 9×103 MPXV genomes per m3 were detected in air samples collected at two health centres in Spain. Therefore, these novel findings and the analysis with aerosol dynamics show that aerosols carrying MPXV could be present in environments where patients have resided and that airborne transmission of MPXV can occur. As to the stability of the virus in air, it was reported that the viability of the airborne MPXV was maintained for 90 h under artificial test conditions in a rotating chamber.

Although the binding affinities of MPXV to human cells are unclear, the airborne transmission route must be considered as a possible transmission mode under the conditions of current experimental and analytical findings. Therefore, monitoring airborne viruses as well as non-pharmaceutical interventions (ventilation, aerosol control, or respirator), will help control the spread of MPXV.

(Note that “90 h” figure, even if the conditions were artificial.)

So CNBC is wrong to write:

Mpox transmits through close physical contact, including sexual contact, but there is no evidence that it spreads easily through the air.

Granted, “easily,” but I think that adverb is doing a lot of work. Smallpox, like monkeyox, is an orthopoxvirus, and smallpox is airborne.

Ditto AP:

Unlike COVID-19 or measles, mpox is not airborne and typically requires close, skin-to-skin contact to spread.

And of course:

Adverbs working hard here, too.

Conclusion

On the bright side, I like those low wastewater readings. Long may they continue! Further on the bright side, I have seen no reports of neurological or vascular damage from Mpox (though some of the reports of lesions from Africa are horrific). Even brighter, it’s easy to do brunch when the lethal pathogen you’re breathing into the air you share with other people is invisible, but not so easy when your skin is covered with visible pustules (though perhaps we should go long face stickers). So perhaps Mpox will stimulate the PMC, at long last, to investigate/invest in non-pharmaceutical interventions!

On the less bright side, this is a disease I don’t ever want to get (though, ancient as I am, my childhood smallpox vaccination may give me a measure of protection; something to investigate). And on the dark side, nothing in our institutional response to Mpox gives me confidence that we have learned anything at all from Covid (except how to repeat our mistakes, if indeed they were mistakes[2]). Stay safe out there!

NOTES

[1] An acronym like “2SLGBTQIAP+” seems to me to call for a measure of reconceptualization.

[2] See NC in 2022 for “CDC Rigs Its Own Monkeypox Case Reports by Not Including Questions on Airborne Transmission.”