Getty Images

Getty ImagesA trial has begun in California to decide whether Stanford University can keep the diaries of a top Chinese official, in a case that is being framed as a fight against Chinese government censorship.

The diaries belong to the late Li Rui, a former secretary to Communist China’s founder Mao Zedong.

Following Li’s death in 2019, his widow sued for the documents to be returned to Beijing, claiming they belong to her.

Stanford rejects this. It says Li, who had been a critic of the Chinese government, donated his diaries to the university as he feared they would be destroyed by the Chinese Communist Party.

The diaries, which were written between 1935 and 2018, cover much of the Chinese Communist Party’s (CCP) rule. In those eight tumultuous decades, China emerged from impoverished isolation to become indispensable to the global economy.

“If [the diaries] return to China they will be banned… China does not have a good record in permitting criticism of party leaders,” Mark Litvack, one of Stanford’s lawyers, told the BBC before the trial began.

The BBC has contacted lawyers representing Zhang Yuzhen, Mr Li’s widow, for comment.

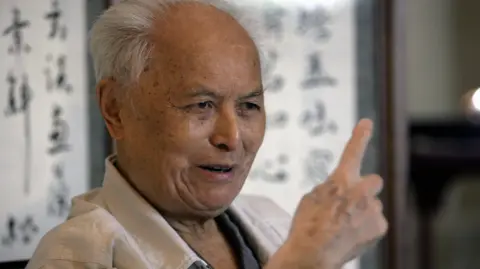

A prominent CCP figure known for his reformist views, Mr Li was both venerated and shunned by the party.

As a young outspoken cadre he caught the eye of Mao who made him one of his personal secretaries in the mid-1950s. But the position was shortlived.

When Li criticised Mao’s views at a political meeting, he was ousted from the party and spent years in prison. He was among hundreds of party officials and public figures, including close allies of Mao, who fell foul of the mercurial leader.

Like some of them, Li returned to prominence after Mao died in 1976. He oversaw the ministry of hydroelectric power and a CCP department that selected officials for key positions. Within the party, he was allied with the more liberal, open-minded faction advocating for reform.

After his retirement, he continued to lobby the party for reform. But his unsparing, sharp-tongued criticism of leaders, including President Xi Jinping – whom he dismissed as “lowly-educated” – needled the government. His writings were censored and his books banned in China.

As a party elder, however, he continued to be treated with respect and enjoyed privileges. When he died he was given a state funeral.

Throughout, as he navigated the echelons of power, he meticulously recorded observations about party politics and key events in his diaries.

These include his account of the Tiananmen Massacre, which he witnessed from a balcony overlooking the square and labelled as “Black Weekend” in English in his diary. It is a highly sensitive issue that is rarely discussed in China.

His daughter, Li Nanyang, began donating his documents, including the diaries, to Stanford’s Hoover Institution in 2014, when he was still alive.

In a 2019 interview with BBC Chinese after his death, she said this fulfilled her father’s wishes.

That year Ms Zhang filed a lawsuit against Li Nanyang – her stepdaughter – in China.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesMs Zhang, who was Li Rui’s second wife, argued that he wanted her to decide which of his documents would be made public and they were wrongfully given to Stanford, according to reports.

The widow said the diaries contained “deeply personal and private affairs” of her life with Li. As the diaries can be accessed by the public at Stanford, she said their display caused her “personal embarrassment and emotional distress”.

A Beijing court ruled in Ms Zhang’s favour and ordered the diaries to be handed over to her.

Stanford has rejected this ruling. Its lawyers have argued that “Chinese courts are not impartial in politically-charged cases such as this” and that the university was not given a chance to defend itself.

The trial that began in California on Monday is over a separate lawsuit launched by the university against Ms Zhang in the US.

Stanford is asking the California court to declare the university as the lawful owner of the diaries.

Its lawyers argue that Li Rui wanted to donate his papers to Stanford because “he understood that the regime would seek to suppress his account of modern Chinese history” and he “feared that the materials would be destroyed”.

Stanford has been allowed to retain copies of the diaries, but it is arguing to keep the original documents as well, to comply with Li’s wishes.

“Li Rui wanted his diaries, including his originals, at Hoover,” Mr Litvack said. “That’s why they are at Hoover and we have fought to keep them at Hoover.”