BBC / Mike Wendling

BBC / Mike WendlingKris Burlingame got a surprise on testing day.

A long-time election volunteer and former clerk in the Wisconsin village of Alma Center, she is well-versed in election law, including the routine requirement to invite the public to watch tests of voting machines.

Usually, nothing happens. No member of the public had actually taken up such an invitation, she said – until one man showed up during the most recent test on 1 August.

“He had just moved into the area and he was belligerent, angry,” Ms Burlingame said.

The middle-aged man started taking pictures and asking questions – how did the machines work? Were the machines connected to the internet? (They weren’t, but he insisted on being shown the internet connections).

“These are the machines that changed everyone’s votes,” the man said, repeating a widely spread and debunked conspiracy theory about a particular brand of voting machine.

“I said, ‘There’s no way they can do that’,” Ms Burlingame recalls. “He was not happy with me.”

Eventually the man left, but the incident gave her pause.

“It made me nervous. I wasn’t afraid… but it did make me stop and think, what is the election going to be like? Are we going to have more of this?”

Incidents like the one in Alma Center, a village of around 500 people in largely rural Jackson County in western Wisconsin, have become increasingly common throughout the country in recent years, experts say.

As a result, officials are preparing for another high-stakes election on 5 November by bolstering security to keep workers safe at polling places. They are also working to protect against possible intimidation of voters or tampering with the voting process.

Threats against election workers have increased since the 2020 presidential election which Donald Trump and his allies falsely claimed to have won.

Conspiracy theories about the voting process led to threats against election workers, and culminated in the 6 January 2021 riot at the US Capitol.

Now, suspicion about elections has become so pervasive that it has moved well beyond urban areas with large vote-counting operations and crept into places like Jackson County. Wisconsin is a battleground state which President Joe Biden won by fewer than 21,000 votes four years ago.

Election workers are on the frontlines.

BBC / Mike Wendling

BBC / Mike WendlingA survey earlier this year by the Brennan Center, a non-partisan but left-leaning think tank, found 38% of local election officials had experienced threats, harassment or abuse.

More than half were concerned about the safety of their colleagues or staff, a level of anxiety that has remained more or less constant since the 2022 midterm elections.

“People are scared,” says Melissa Kono, the elected town clerk in Burnside, Wisconsin.

Ms Kono travels around Wisconsin delivering state-mandated election training to volunteer poll workers.

She says the kinds of scenarios she’s being asked about have changed dramatically over the last five years, to the point where she’s increasingly included material in her sessions about dealing with threats.

“I’m concerned for the clerks and the election workers,” she said.

Ms Kono told the BBC that she and other elections officials are considering scenarios that were unthinkable just a few years ago, such as planning for active shooters at voting places.

Her handouts to local workers now include a list of emergency numbers, useful in the case of extreme weather and natural disasters, but also threats of violence.

“When people perceive the stakes as being very high, they’re willing to do extreme actions in order to win,” she said during a break in one of the sessions at the courthouse in Black River Falls which, with a population of 3,500, is the largest settlement in Jackson County.

“It’s one thing to prepare workers for the things that are in the election day manual, such as, how do you process absentee ballots? What are the photo ID requirements?

“But it’s all these things that I just can’t even anticipate,” she said. “I worry that I didn’t prepare them to be safe.”

BBC / Mike Wendling

BBC / Mike WendlingMs Kono and other election officials’ shared their concerns as the threat of further political violence looms over this year’s election.

Donald Trump himself narrowly escaped an assassination attempt on his life in Pennsylvania in July, and avoided a second attempt at his golf course in Florida in September.

Among other incidents, elections officials have been sent white powder in the post, and have been subjected to “swatting” – anonymous emergency calls about fictional crimes, designed to draw armed police into people’s homes.

At the same time, Trump and his allies have continued to sow doubts about the integrity of the US voting system, which is marked by a patchwork of rules, regulations and methods, making November’s vote less of a national ballot than an interlocking network of thousands of local elections.

In 2016, he said – with no real evidence – that millions of votes had been fraudulently cast, but the conspiracy theories reached a fever pitch in 2020, when the Covid pandemic prompted many states to change laws to make it easier to vote early and by mail or absentee ballot.

Although the 2022 midterms were mostly peaceful, experts say false information about elections has persisted and has the potential to instigate disruption or even violence.

“When I served as an election official, I didn’t receive death threats,” says Elizabeth Howard, a director at the Brennan Center and a former deputy commissioner of elections in Virginia.

Ms Howard said the nearly two-fifths of election workers facing threats represent “very concerning numbers”.

“Not surprisingly, these threats are leading to election officials leaving the profession,” she said.

In 2021 the US justice department set up a task force to investigate threats against election workers, and has since examined more than 2,000 threats. But only a small number of cases – 20, at the last count – have resulted in criminal charges.

Ms Howard noted that recent threats are not a partisan issue, with the vast majority of election officials taking steps to increase security since 2020.

The most common measure being taken is collaborating with law enforcement, she said, but some polling places have installed panic buttons, bullet-resistant glass panels or electronic security measures.

“Election officials on both sides of the aisle have been threatened,” she said.

That includes Republican Bill Gates – no relation to the Microsoft founder – who as supervisor of Maricopa County, Arizona, found himself on the receiving end of threats in 2020 and 2022.

“It’s something that people talk about all the time,” he said, noting that people have been spotted taking pictures of election workers and their licence plates outside the county tabulation centre in the state’s largest city, Phoenix.

“People are still questioning the 2020 election almost every day,” he told the BBC.

“If you take a look at my X account, it’s just constant.

“I’ll type something like ‘I had a sandwich today’ and (someone will respond) ‘You stole the election in 2020’.”

“It shouldn’t be like this,” he said. “People who are in elections should not be subjected to this vitriol, to the insults… it’s just crazy.”

Gates suffered from post-traumatic stress and for a variety of reasons is not running for re-election as Maricopa supervisor this year.

Getty Images

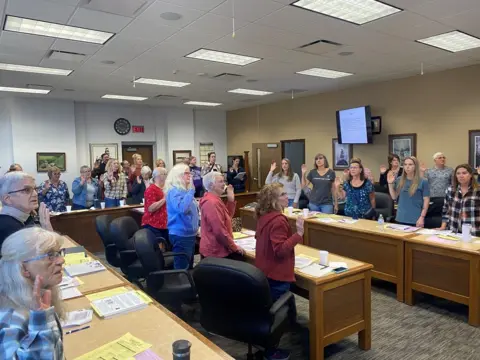

Getty ImagesBack in Wisconsin, around 50 Jackson County election volunteers crowded into a courthouse room lightly adorned with paintings and prints of local rural scenes to attend one of Ms Kono’s training sessions in early October.

“No one is allowed to be disruptive,” she told them, explaining the regulations around partisan poll watchers, or “election observers” as they are called in Wisconsin. “Observers have some rules they have to follow” – they can’t wear buttons or hats in support of a candidate, and they have to stay in a designated area.

“You don’t have to make them comfortable, right?” one volunteer asked.

“I don’t think the election manual says,” Ms Kono responded, smiling as chuckles broke out around the room. “Well, I wouldn’t feed them.”

There are dozens of slides on election procedures and rules, and talk to threats and security. Ms Kono explained the difference between a “true threat” – threatening an election official is illegal in Wisconsin – and an angry, but legal, comment. She distributed the packets that she had prepared with local emergency contacts and other useful phone numbers.

“You should really be aware of a lot of things on election day,” she told the group.

Not everyone in Black River Falls is so worried about the safety of election workers.

BBC / Mike Wendling

BBC / Mike WendlingIn the local Republican County office, a short walk down Main Street, Republican county chairman Bill Laurent was more sanguine.

“This is the kind of place where you go to the polls and the workers will have a cookie or a piece of cake for you,” he said. “I haven’t heard of much trouble.”

But reflecting the views of national party leadership, Mr Laurent said he was not confident that voting would be fair beyond Jackson County – citing in particular his fears of dirty tricks in Democratic strongholds in Wisconsin’s two biggest cities, Madison and Milwaukee.

Meanwhile the potential for escalating threats to affect voting was playing on the minds of several of the volunteers here, including Ms Burlingame, who dealt with the aggressive voting machine sceptic in August.

Prior to 2020, she said, she would have put the chances of disruption on election day near zero.

“Now I think it’s kind of four or five,” on a ten-point scale, she said.

“I don’t think anything’s going to happen, but I’m not going to have a blind eye,” she said. “There’s just some people that I just don’t feel I could trust, and that scares me.”

North America correspondent Anthony Zurcher makes sense of the race for the White House in his twice weekly US Election Unspun newsletter. Readers in the UK can sign up here. Those outside the UK can sign up here.