Getty Images

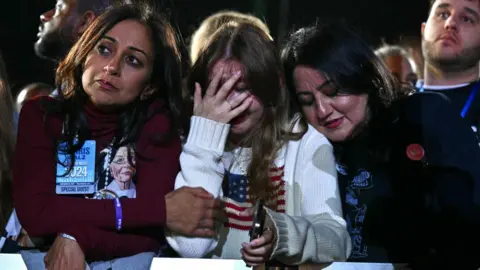

Getty ImagesIn an election full of uncertainties, one thing at least felt likely – women across the US were going to turn out for Kamala Harris.

Just as months of relentless polling showed Harris in a virtual tie with Donald Trump, many of those same surveys told the story of a yawning gender gap.

It was a strategy Harris’s team was betting on, hoping that an over-performance among women could make up for losses elsewhere.

It didn’t happen.

Across the country, the majority of women did cast their ballots for Harris, but not by the historic margins she needed. Instead, if early exit polls bear out, Harris’s advantage among women overall – around 10 points – actually fell four points short of Joe Biden’s in 2020.

Democrats suffered a 10 point drop among Latino women, while failing to move the needle among non-college educated women at all, who again went for Trump 63-35, preliminary data suggests.

The shortfall was not for lack of trying.

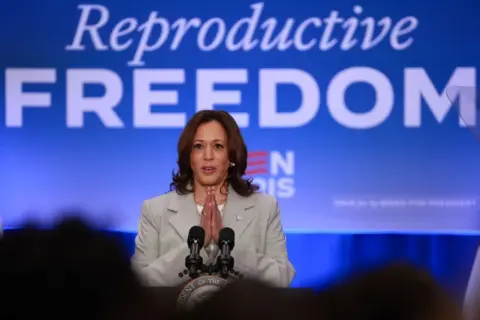

Throughout her 15-week campaign, much of Harris’s messaging was aimed directly at women, most obviously with her emphasis on abortion.

On the trail, Harris made reproductive rights a cornerstone of her pitch. She repeatedly reminded voters that Trump had once bragged about his role in overturning Roe v Wade – a ruling that ended the nationwide right to an abortion.

“I will fight to restore what Donald Trump and his hand-selected Supreme Court justice took away from the women of America,” Harris said at her closing address in DC last week.

Her most powerful advertisements featured women who had suffered under state abortion bans – deemed “Trump abortion bans” by Harris – including those who said they were denied care for miscarriages.

The strategy, it seemed, was to harness the same enthusiasm for abortion access that drove Democrats’ unexpected success in the 2022 midterms.

Abortion rights remain broadly popular – this Gallup poll in May suggested only one in 10 Americans thought it should be banned.

And even these election results seemed to underline that. Seven out of the 10 states where abortion was on the ballot voted in favour of abortion rights.

But that support did not translate into support for Harris.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesAbortion did matter to women, it just didn’t matter enough, said Evan Roth Smith, a pollster and campaign consultant.

“Voters – particularly the women – who feel strongest about abortion are already voting for Democrats,” he said. But Democrats were unable to raise the importance of abortion for women who didn’t yet see it as a pressing issue.

“The abortion argument did not penetrate at all with non-college educated women, did not move them an inch. And they lost ground with Latinos,” Mr Smith said.

For many, the decisive issue proved to be the economy.

In pre-election surveys and preliminary exit data, inflation and affordability continued to top lists of voters’ concerns. And for these voters, Trump was the overwhelming favourite.

Jennifer Varvar, 51, an independent from Grand Junction, Colorado said she had not even considered a vote for Harris because of the financial stress she faced over the past four years.

“For me and my family, we’re in a worse position now than we ever have been financially. It’s a struggle. I have three boys to put food on the table for,” she said. Things had been better under Trump, she said, and that’s why she voted for him.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesBut if gender didn’t divide the electorate in the way some expected, it still played a part in the Harris defeat, say some analysts.

There have been many explanations offered for Trump’s resounding victory but for some there is one thing that stands out.

“I do think that the country is still sexist and is not ready for a woman president,” said Patti Solis Doyle, who managed Hillary Clinton’s 2008 presidential campaign, to Politico.

Unlike Clinton, who explicitly leaned into her gender and the history-making potential of her campaign, Harris was noticeably reluctant to do the same.

There is a widespread belief that the country is more ready for a woman president now than when Clinton ran a second time in 2016. But it’s still an open question.

A Reuters/Ipsos poll in October suggested 15% of those surveyed would not be able to vote for a female president.

And Donald Trump, who doubled down on masculinity in this election, may have played a part in exploiting that.

“He framed being president as being a tough guy in a dangerous world… he framed that as the job description,” said Mr Smith.

“And that’s one of the hardest possible job descriptions for a woman to successfully meet, in the minds of many Americans.”