Later in this piece, we will republish in full a fine, recent Wolf Richter post,

Office CMBS Delinquency Rate Spikes to 10.4%, Just Below Worst of Financial Crisis Meltdown. Fastest 2-Year Spike Ever and up front, discuss how it contrasts with the Wall Street Journal’s attempt to depict the commercial office space market as on the mend.

Mind you, Wolf and the Journal are discussing two different markets, even though tenant payments on office leases are a big common element in their economics. But the commercial real estate mortgage securities are composed of pools of loans from banks. These structures are much better than the ones for residential mortgages. A key difference is because these are fewer and bigger loans, the servicer is authorized and paid to renegotiate loans when a borrower gets in trouble

However, it is important to keep in mind that banks generally keep their best loans for themselves and sell most of the others. They may retain some exposure to the loans they sell to securitizers. So you would expect much lower delinquency rates on the bank-owned mortgages than on commercial real estate mortgage bonds, o CMBS.

The Journal’s coverage has tended to focus on the performance of commercial real estate loans held by banks, while it has in the post-Covid era, stories focused on the health of the big office market. That can be confusing for readers since commercial real estate extend beyond office properties and includes categories like malls and warehouses. The health, or lack thereof, of the office market has become a big class warfare story as workers told to operate from home continue to fight having to turn up every day. Even though many big companies have tried tightening the screws, occupancy rates in major cities are still way down. And that has in turn has had knock-on effects to the vibrancy of cities, the viability of many retailers and small businesses that catered to commuters, and urban tax receipts.

Commercial real estate lending got more attention due to its potential to intensive problems at banks that had badly wrong-footed the interest cycle, as well as being of perennial interest to bank stock investors.

To turn now to some of Wall Street Journal’s recent pieces, it has usefully reported that even though smaller community banks were thought to more at risk, that turned out not to be true. From the Journal in July, on data analyses as of the end of the first quarter:

Such things as credit-card loans are pretty standardized, but real estate is fuzzier. Is it a new-construction loan or one on an existing building? Is the borrower the property’s main tenant or is it looking to lease the building out? Is it an office tower, a medical facility, a strip mall or a warehouse? Is it a big loan split between banks, or a smaller one held by one bank? And so on….

The trouble is at big banks and their loans to properties that are intended to be leased to third parties. For CRE loans involving properties that aren’t owner-occupied and are held by banks with over $100 billion in assets, more than 4.4% were delinquent or in nonaccrual status in the first quarter. That was up over 0.3 percentage point from the prior quarter. Meanwhile, in each of the size categories of banks below $100 billion in assets, as well as for those bigger banks’ owner-occupied loans, the rate was below 1% in the first quarter.

Attentive readers might note that these lagged figures are way below what Wolf is reporting in his new piece. One possible reason for the difference is the presumed higher quality and therefore lower losses on loans retained by banks. But the big one is the outsized poor performance of the office loans and how they have deteriorated markedly:

One can anticipate that delinquencies on bank-retained loans will follow a similar trajectory, if much less steep. But a 3rd quarter report from S&P includes some grim numbers from big banks. These figures are non-performing loans, which typically means delinquent for more than 90 days, so a much more severely impaired loan than delinquent:

Nonperforming office loans trended down at several major office lenders but rose sharply for others in the third quarter.

Wells Fargo reported $29.0 billion in office loans, 3.2% of its gross loans held for investment. Its office portfolio was 12.2% nonperforming, down slightly from the second quarter’s 12.3%. The company raised reserves against the portfolio to 8.3% from 8.0%.

PNC’s office loans of $7.2 billion, or 2.2% of loans held for investment, rose to 12.5% nonperforming from 11.0% the prior quarter. In tandem, reserves against them rose a percentage point to 11.3% from 10.3%.

Citizens Financial Group Inc. had the highest reserve ratio in the analysis at 12.1% of its general office portfolio.

Nonperforming loans (NPLs) at Regions Financial Corp. accounted for 14.5% of total office loans, the largest proportion of the 13 banks with available data. However, that ratio dropped from 15.1% in the prior quarter, and office reserves rose to 6.8% from 6.4%. The company’s office loans of $1.6 billion account for only 1.6% of gross loans held for investment.

First Citizens BancShares Inc. recorded the second-highest nonperforming ratio, with NPLs accounting for 13.6% of its general office segment, a decrease of 2.4 percentage points from the prior quarter.

Independent Bank Corp.’s NPLs as a proportion of total office loans rose 5.2 percentage points quarter over quarter to 7.1%.

These are the ugliest from an analysis of 26 big banks, and “ugly” is no understatement.

Now to the happy talk from an October 29 Wall Street Journal story, Bosses Are Calling Workers Back to the Office. That’s Good News for Landlords:

More companies are backing away from the looser workplace policies they adopted during the early years of the pandemic as executives increasingly recommit to promoting an office culture….

One-third of all companies required workers to be in the office five days a week in the third quarter, up from 31% in the second quarter, according to Flex Index, which tracks workplace strategies.

That terminated a streak over the previous five quarters when that rate had steadily fallen. One reason for that decline was because low unemployment gave employees leverage when pressing for more remote work. Now, the white-collar workforce isn’t growing as much, shifting the balance of power back to managers.

No one sees workplaces returning to prepandemic patterns, but most believe the worst is likely over for the office sector.

“We looked like we were on a path that we were going to see a drop continue quarter after quarter,” said Rob Sadow, chief executive of Flex Index. “All of a sudden in the third quarter we saw a shift in direction.”

Note that Flex Index only tracks “strategies,” not outcomes. Will some employers make quiet concessions?

Only at this point does the story concede that this amount to at best a small amount of improvement from a low baseline:

These signs of stabilization hardly signal an end to office-market turmoil.

The vacancy rate is stabilizing at a near record level of 13.8%, up from 9.4% in the fourth quarter in 2019. Since the second quarter of 2020, U.S. office tenants have vacated close to 209 million square feet of space, the highest amount ever for a four-and-half-year period, according to data firm CoStar Group.

A lot of the current empty office space is now considered obsolete. It may never be filled.

Defaults and other missed payments also continue to rise. In September, the delinquency rate of office loans converted into securities increased to 8.36%, the highest rate since November 2013, according to data firm Trepp.

Trepp is the same source for Wolf’s 10.4% figure. So the Journal was hardly doing readers and investors a favor by finding a robin and declaring it to be spring.

As you’ll see in Wolf’s post below, swathed of empty office buildings is a structural problem. There are secondary locations, like Madison Avenue in the 30s that will probably never come back. In Wall Street, when the center of the finance industry moved to midtown, enough building had water views from two sides and small enough footprints to allow for them to be converted to residential space. Office buildings with large central footprints, and often worse with at most one side having reasonable views, are big white elephants.

Now to Wolf.

By Wolf Richter, editor at Wolf Street. Originally published at Wolf Street

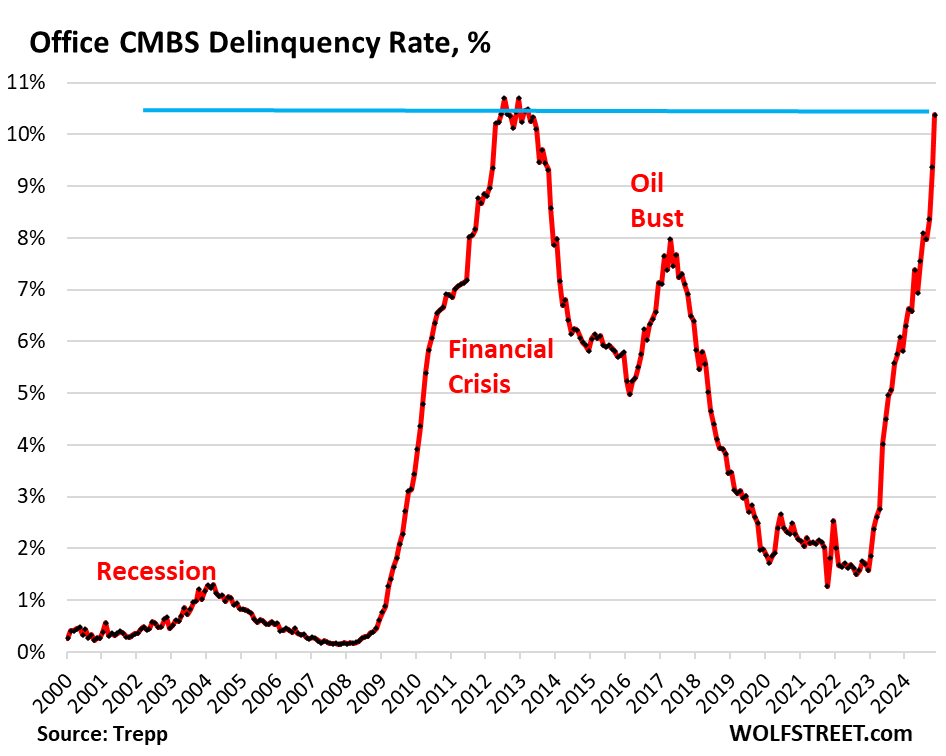

The delinquency rate of office mortgages that have been securitized into commercial mortgage-backed securities (CMBS) spiked by a full percentage point in November for the second month in a row, to 10.4%, now just a hair below the worst months during the Financial Crisis meltdown, when office CMBS delinquency rates peaked at 10.7%, according to data by Trepp, which tracks and analyzes CMBS.

Over the past two years, the delinquency rate for office CMBS has spiked by 8.8 percentage points, far faster than even the worst two-year period during the Financial Crisis (+6.3 percentage points in the two years through November 2010).

The office sector of commercial real estate has entered a depression, and despite pronouncements earlier this year by big CRE players that office has hit bottom, we get another wakeup call:

Amid historic vacancy rates in office buildings across the country, more and more landlords have stopped making interest payments on their mortgages because they don’t collect enough in rents to pay interest and other costs, and they can’t refinance maturing loans because the building doesn’t generate enough in rents to cover interest and other costs, and they cannot get out from under it because prices of older office towers collapsed by 50%, 60%, 70%, or more, and with some office towers becoming worthless and the property going for just land value.

Mortgages count as delinquent when the landlord fails to make the interest payment after the 30-day grace period. A mortgage doesn’t count as delinquent if the landlord continues to make the interest payment but fails to pay off the mortgage when it matures, which constitutes a repayment default. If repayment defaults by a borrower who is current on interest were included, the delinquency rate would be higher still.

Loans are pulled off the delinquency list when the interest gets paid, or when the loan is resolved through a foreclosure sale, generally involving big losses for the CMBS holders, or if a deal gets worked out between landlord and the special servicer that represents the CMBS holders, such as the mortgage being restructured or modified and extended. And there has been a lot of extend-and-pretend this year, which has the effect of dragging the problem into 2025 and 2026.

Of the major sectors in CRE, office is in the worst shape with a delinquency rate of 10.4%, far ahead of lodging (6.9%), permanently troubled retail (6.6%), and multifamily (4.2%). Industrial, such as warehouses and fulfillment centers, is still in pristine condition (0.3%) due to the continued boom in ecommerce.

The problem with office CRE isn’t a temporary blip caused by a recession or whatever, but a structural problem – a massive glut of useless older office buildings – that won’t easily go away. The glut is a result of years of overbuilding and industry hype about the “office shortage” that led companies to hog office space as soon as it came on the market in order to grow into it later. But during the pandemic, they realized they don’t need this still unused office space, and they put it on the market for sublease, adding to the glut.

The motto in 2024 was “survive till 2025,” driven by hopes that the Fed would unleash massive rate cuts and drive rates to the bottom.

A lot of CRE loans are floating-rate loans whose interest rates adjust with short-term rates, such as x percentage points over SOFR. And pushing interest rates back down to rock bottom might give some of these properties a chance.

The Fed has cut interest rates, but its five short-term policy rates are still between 4.5% and 4.75%, and SOFR was at 4.57% on Friday, amid lots of talk from the Fed about slowing the cuts and stopping them earlier than expected, while long-term rates have risen since the first rate cut on renewed inflation fears.

But whatever rate cuts the Fed will eventually get done cannot address the structural issues that office CRE faces. Owners of nearly empty older office towers won’t be able to make the interest payments even at lower interest rates.

The current “flight to quality” is making the fate of older office towers even worse. High vacancy rates in the latest and greatest buildings allow companies to move from an old office tower to the latest and greatest tower, some downsizing in the process, and they’re doing it, thereby speeding up the demise of the older tower.

Conversions of old office towers to residential are taking place, and the numbers are growing but minuscule because many office towers cannot be converted for a variety of reasons, including their large square floorplates and the costs of conversion to where it would be cheaper to tear them down and start from scratch with a modern building.

In 2019, across the US, 56 office buildings were converted into residential, based on their dates of completion, according to data from CBRE, cited by the WSJ. That pace continued in 2020 and 2021. By 2023, the pace ticked up to 63 conversions. And in 2024, 73 conversions were completed and 30 conversions are under way. In 2025, 94 conversions are expected to get completed with another 185 planned, for a total of 279 conversions.

There are now 71 million square feet of conversions planned or under way. But that’s a drop in the bucket. That would account for just 7.9% of the 902 million square feet of vacant office space in the US, according to estimates by Moody’s.

Thankfully for the US banking system, a big part of office mortgages has been broadly spread across investors around the world and across foreign banks, not just US banks. For years, there was this assumption that you cannot lose money in real estate, especially office CRE in prime US markets, and investors around the globe piled into it.

Office mortgages are held by CMBS and CLO investors, such as bond funds, by insurers, by private or publicly traded office REITs and mortgage REITS, by PE firms, by private credit firms, and other investment vehicles, and by foreign banks. Those mortgages pose no threat to the US banking system.

US banks have some exposure to office mortgages, and there have been some big write-offs already, and lots of extend-and-pretend under the motto “survive till 2025.” Some smaller US banks have concentrations of office mortgages on their books, and so they have to deal with them, take the losses, crush their shareholders, etc., and some might eventually choke to death on their office mortgages. But none have so far.