Yves here. Rajiv Sethi describes a fascinating, large-scale study of social media behavior. It looked at “toxic content” which is presumably actual or awfully close to what is often called hate speech. It found that when the platform succeeded in reducing the amount of that content, the user that had amplified it the most both reduced their participation overall but also increased their level of boosting of the hateful content.

Now I still reserve doubts about the study’s methodology. It used a Google algo to determine what was abusive content, here hostile speech directed at India’s Muslim population. Google’s algos made a complete botch of identifying offensive text at Naked Capitalism (including trying to censor a post by Sethi himself, cross posted at Naked Capitalism), to the degree that when challenged, they dropped all their complaints. Maybe this algo is better but there is cause to wonder without some evidence.

What I find a bit more distressing is Sethi touting BlueSky as a less noxious social media platform for having rules for limiting content viewing and sharing that align to a fair degree with the findings of the study. Sethi contends that BlueSky represents a better compromise between notions of free speech and curbs on hate speech than found on current big platforms.

I have trouble with the idea that BlueSky is less hateful based on the appalling treatment of Jesse Singal. Singal has attracted the ire of trans activists on BlueSky for merely being even-handed. That included falsely accusing him of publishing private medical records of transgender children. Quillette rose to his defense in The Campaign of Lies Against Journalist Jesse Singal—And Why It Matters. This is what happened to Singal on BlueSky:

This second round was prompted by the fact that I joined Bluesky, a Twitter alternative that has a base of hardened far-left power users who get really mad when folks they dislike show up. I quickly became the single most blocked account on the site and, fearful of second-order contamination, these users also developed tools to allow for the mass-blocking of anyone who follows me. That way they won’t have to face the threat of seeing any content from me or from anyone who follows me. A truly safe space, at last.

But that hasn’t been enough: They’ve also been aggressively lobbying the site’s head of trust and safety, Aaron Rodericks, to boot me off (here’s one example: “you asshole. you asshole. you asshole. you asshole. you want me dead. you want me fucking dead. i bet you’ll block me and I’ll pass right out of existence for you as fast as i entered it with this post. I’ll be buried and you won’t care. you love your buddy singal so much it’s sick.”). Many of these complaints come from people who seem so highly dysregulated they would have trouble successfully patronizing a Waffle House, but because they’re so active online, they can have a real-world impact.

So, not content with merely blocking me and blocking anyone who follows me, and screaming at people who refuse to block me, they’ve also begun recirculating every negative rumor about me that’s been posted online since 2017 or so — and there’s a rich back catalogue, to be sure. They’ve even launched a new one: I’m a pedophile. (Yes, they’re really saying that!)

Mind you, this is only the first section of a long catalogue of vitriolic abuse on BlueSky.

IM Doc did not give much detail, but a group of doctors who were what one might call heterodox on matters Covid went to BlueSky and quickly returned to Twitter. They were apparently met with great hostility. I hope he will elaborate further in comments.

Another reason I am leery of restrictions on opinion, even those that claim to be mainly designed to curb speech, is the way that Zionists have succeeded in getting many governments to treat any criticism of Israel’s genocide or advocacy of BDS to try to check it as anti-Semitism. Strained notions of hate are being weaponized to censor criticism of US policies.

So perhaps Sethi will consider the reason that BlueSky appears more congenial is that some users engage in extremely aggressive, as in often hateful, norms enforcement to crush the expression of views and information in conflict with their ideology. I don’t consider that to be an improvement over the standards elsewhere.

By Rajiv Sethi, Professor of Economics, Barnard College, Columbia University &; External Professor, Santa Fe Institute. Originally published at his site

The steady drumbeat of social media posts on new research in economics picks up pace towards the end of the year, as interviews for faculty positions are scheduled and candidates try to draw attention to their work. A couple of years ago I came across a fascinating paper that immediately struck me as having major implications for the way we think about meritocracy. That paper is now under revision at a flagship journal and the lead author is on the faculty at Tufts.

This year I’ve been on the alert for work on polarization, which is the topic of a seminar I’ll be teaching next semester. One especially interesting new paper comes from Aarushi Kalra, a doctoral candidate at Brown who has conducted a large-scale online experiment in collaboration with a social media platform in India. The (unnamed) platform resembles TikTok, which the country banned in 2020. There are now several apps competing in this space, from multinational offshoots like Instagram Reels to homegrown alternatives such as Moj.

The platform in this experiment has about 200 million monthly users and Kalra managed to treat about one million of these and track another four million as a control group.1 The treatment involved replacing algorithmic curation with a randomized feed, with the goal of identifying effects on exposure and engagement involving toxic content. In particular, the author was interested in the viewing and sharing of material that was classified as abusive based on Google’s Perspective API, and was specifically targeted at India’s Muslim minority.

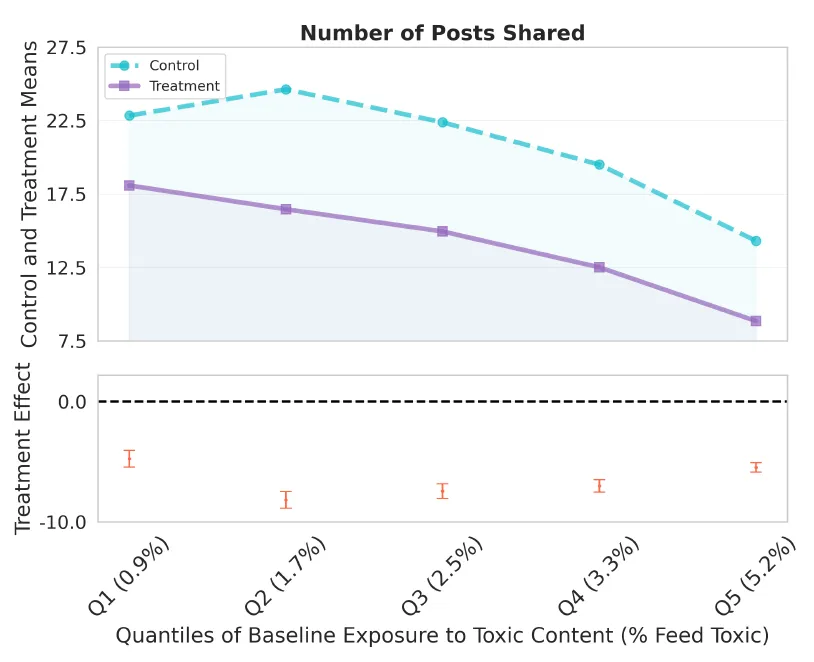

The results are sobering. Those in the treated group who had previously been most exposed to toxic content (based on algorithmic responses to their prior engagement) responded to the reduction in exposure as follows. They lowered overall engagement, spending less time on the platform (and more on competing sites, based on a subsequent survey). But they also increased the rate at which they shared toxic content conditional on encountering it. That is, their sharing of toxic content declined less than their exposure to it. They also increased their active search for such material on the platform, thus ending up somewhat more exposed than treated users who were least exposed at baseline.

Now one might argue that switching to a randomized feed is a very blunt instrument, and not one that platforms would ever implement or regulators favor. Even those who were most exposed to toxic content under algorithmic curation had feeds that were predominantly non-toxic. For instance, the proportion of content classified as toxic was about five percent in the feeds of the quintile most exposed at baseline—the remainder of posts catered to other kinds of interests. It is not surprising, therefore, that the intervention led to sharp declines in engagement.

You can see this very clearly by looking at the quintile of treated users who were leastexposed to toxic content at baseline. For this set of users, the switch to the randomized feed led to a statistically significant increase in exposure to toxic posts:

Source: Figure 1 in Kalra (2024)

These users were refusing to engage with toxic content at baseline, and the algorithm accordingly avoided serving them such material. But the randomized feed did not do this. As a result, even these users ended up with significantly lower engagement:

In principle, one could imagine interventions that degrade the user experience to a lesser degree. The author uses model-based counterfactual simulations to explore the effects of randomizing only a proportion of the feed for selected users (those most exposed to toxic content at baseline). This is interesting, but existing moderation policies usually target content rather than users, and it might be worth exploring the effects of suppressed or reduced exposure only to content classified as toxic, while maintaining algorithmic curation more generally. I think the model and data would allow for this.

There is, however, an elephant in the room—the specter of censorship. From a legal, political, and ethical standpoint, this is more relevant for policy decisions than platform profitability. The idea that people have a right to access material that others may find anti-social or abusive is deeply embedded in many cultures, even if it is not always codified in law. In such environments the suppression of political speech by platforms is understandably viewed with suspicion.

At the same time, there is no doubt that conspiracy theories spread online can have devastating real effects. One way to escape the horns of this dilemma may be through composable content moderation, which allows users a lot of flexibility in labeling content and deciding which labels they want to activate.

This seems to be the approach being taken at Bluesky, as discussed in an earlier post. The platform gives people the ability to conceal an abusive reply from all users, which blunts the strategy of disseminating abusive content by replying to a highly visible post. The platform also allows users to detach their posts when quoted, thus compelling those who want to mock or ridicule to use (less effective) screenshots instead.

Bluesky is currently experiencing some serious growing pains.2 But I’m optimistic about the platform in the long run, because the ability of users to fine-tune content moderation should allow for a diversity of experience and insulation from attack without much need for centralized censorship or expulsion.

It has been interesting to watch entire communities (such as academic economists) migrate to a different platform with content and connections kept largely intact. Such mass transitions are relatively rare because network effects entrench platform use. But once they occur, they are hard to reverse. This gives Bluesky a bit of breathing room as the company tries to figure out how to handle complaints in a consistent manner. I think that the platform will thrive if it avoids banning and blocking in favor of labeling and decentralized moderation. This should allow those who prioritize safety to insulate themselves from harm, without silencing the most controversial voices among us. Such voices occasionally turn out, in retrospect, to have been the most prophetic.

________

1

The statistical analysis in the paper is based only on Hindi language users who were active in the baseline period, reducing the sample size to about 232 thousand from 5 million. Of these, about 63 thousand were in the treatment group. I find this puzzling—with random assignment to treatment, the share of treated users in the subsample should be about 20 percent, as in the full sample, but it is above 27 percent. Perhaps I’m missing something obvious, and will update this footnote once I figure this out.

2

See, for example the reaction to Kevin Bryan’s announcement of a new AI assistant designed to enhance student learning. I have been exploring this tool (with mixed results) but it already seems clear to me that rather than putting teaching assistants out of work, such innovations could reduce drudgery and make the job more fulfilling.