Yves here. It’s always perilous to take issue with some of the theories advanced in a book second-hand, as in a review. However, one of the contentions that Tom Neuburger recaps from the Alfred McCoy book, To Govern the Globe, looks to be at a high level of McCoy’s argument and plainly stated, so our disagreement does not seem liked to be based on a misapprehension.

McCoy argues for the durability, albeit with less ability to force compliance than empires, of what he calls world order. He depicts the British imperial order starting in 1815 as distinct from the “Washington world system” that began in 1945.

However, the period of US dominance depended heavily upon the system and (one hates to say it) values of the British empire, particularly when one sets the start date at the end of the Napoleonic Wars, which happens to be when the UK had entered the Industrial Revolution and so the power of landowners was being displaced by the power of merchants and industrialist.

The shared element of both world orders includes:

Common law legal systems with a very large number of similar principles, such as the status of legal contracts, fiduciary duty and limited liability companies

Professional bureaucracies. Before Niall Ferguson started losing his mind, he wrote a fine book, The Cash Nexus, in which he attributed the UK’s ability to punch above its weight in military terms against France was its ability to borrow money in international markets at lower rates. That in turn resulted from England having professional (as in salaried) tax collectors, versus France’s corrupt tax “farmers”

Embrace of financial capitalism as opposed to industrial capitalism; with that came fierce opposition to Communism

Use of English as the lingua franca

Protestantism and Protestant values, particularly deferred gratification; a distaste for mysticism and Orientalism; proselytizing as an aid in influencing/controlling vassal territories

Sea powers that invested in protecting trade routes (admittedly the US later also became an air power but the UK had started down that path)

Those of you who have read McCoy are encouraged to tell me if and how he addresses issues like these. But absent an explanation, yours truly is predisposed to see the Washington era as an adaptation of the British model, and not a new world order.

By Thomas Neuburger. Originally published at God’s Spies

As we enter the next phase of the imperial Western experiment … as we wait for announcements that will firm up our understanding of the pivot our President takes … as we watch dismantled what should never, perhaps, have been built, it’s useful to take a long view of what we’ve done, how long we’ve done it, and how America’s turn as king of the place was thought out and managed. Until it wasn’t — wasn’t thought out; wasn’t very well managed.

This story is different than what you may have heard. You might have thought, for example, that Obama’s claim to have created the fracking boom was just his ego speaking. Or that his final push for TPP was just a beg for post-official wealth. Yes, they were likely those things; but they were both more. Obama had a grand strategy that died when he left office, one that matches the recommendations of the 19th Century naval officer Alfred Thayer Mahan and has been followed by U.S. minds from before, during, and after World War II.

That strategy: Control the combined “big island” of Europe and Asia by controlling its coasts and inland population. It’s why, before World War II, our Western forward bases were at Asia’s front door.

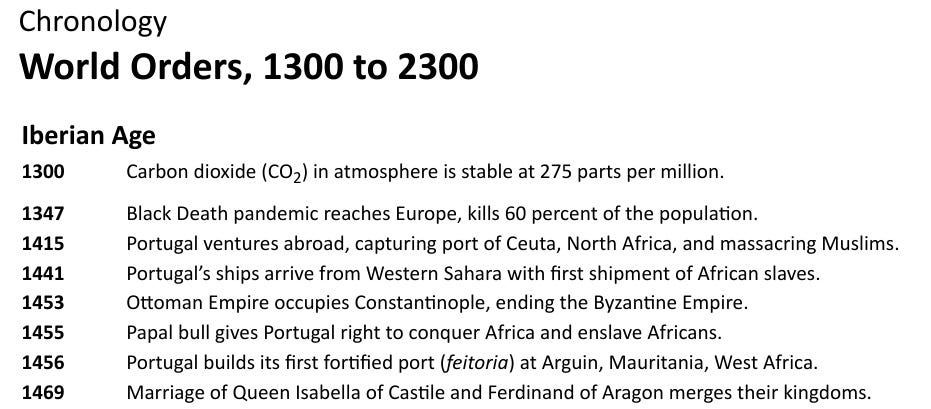

To do this, we’ll take long looks over the next several weeks at the book pictured above: Alfred McCoy’s To Govern the Globe. It’s a massive history of what I’ve called above the “imperial Western experiment.” It covers all the “world orders”: the Iberian, birthed in Portugal and Spain; the British, with which we’re familiar; the American, which sadly few of us understand; and the next, what’s coming for us, the wolf or the Chinese, whichever, and probably both.

The story begins in the early 1400s and starts like this:

If you read that carefully, you see how brutality is the key to success.

1415 Portugal ventures abroad, capturing port of Ceuta, North Africa, and massacring Muslims.

1441 Portugal’s ships arrive from Western Sahara with first shipment of African slaves.

The Pope gave permission in 1455, and the race (and the rape) was on.

About World Orders

There’s a difference between world orders and world empires. Empires are things created; they come and go. Orders are ideas; they tend to persist. McCoy:

[From Chapter 1]

Despite their aura of awe-inspiring power, empires tend to be ephemeral creations of an individual conqueror like Alexander the Great or Napoleon Bonaparte that fade quickly after their death or defeat. By contrast, world orders are much more deeply rooted, resilient global systems created by a convergence of economic, ideological, and geopolitical forces. On the surface, they entail diplomatic agreement among the most powerful nations, which are usually those with formal empires or international influence. Lacking the sovereignty of nations and the raw power of empires, world orders are essentially broad agreements about relations among nation-states and their peoples, lending them an amorphous, even elusive quality.

At a deeper level, however, world orders entwine themselves in the cultures, commerce, and values of countless societies. They influence the languages people speak, the laws that order their lives, and the ways they work, worship, and even play. They are woven into the fabric of an entire civilization, with a consequent capacity to far outlive the empires that formed them. If the economic globalization of the past two centuries was a process, then the current world order is its ultimate product. World orders have much less visible power than empires, but they are more pervasive and persistent. To uproot such a deeply embedded global system takes an extraordinary event, even a catastrophe. Across the span of five continents and seven centuries, a series of calamities—from the devastating epidemics of 1350 through the coming climate crisis of 2050—has produced a relentless succession of rising empires and fading world orders.

… Since the start of the age of exploration in the fifteenth century, some 90 empires, major and minor, have come and gone.23 In those same five hundred years, however, there have been just three world orders, all arising in the West—the Iberian age after 1494, the British imperial era from 1815, and the Washington world system from 1945 to perhaps something like 2030. [emphasis mine]

“Age of exploration” is polite. “Age of exploitation” is more accurate, since, as you’ll see, that’s the most common thread. Man’s inhumanity to man, globally expressed.

Why Study World Orders?

We’re looking at this now because it’s interesting. But more than that, we stand at a pivot from one order to the next, or worse, from one order to none, to dis-integration.

• What do these orders look like? On what strategies are they based? Why is the Pacific integral to them all?

• What’s America’s contribution? What makes the U.S. unique?

• And perhaps the biggest questions of them all: Was the whole thing, the project, worth doing to start with? And why did it start in the West?

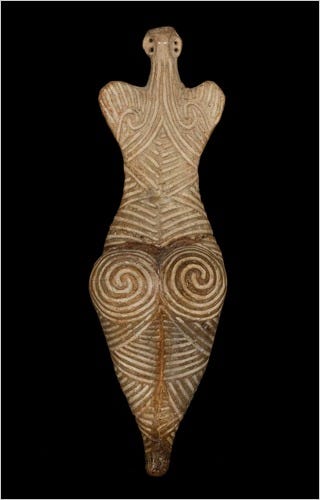

Perhaps the original sin, as it were, was the existence of the proto-Indo-European “sky father” god, Dyḗus ph₂tḗr (Deus phter, “Zeus pater” to the Romans), who led a conquering people of the steppes as they swept before them neolithic humans who worshiped creatures they honored with statues like this:

What’s Special About the West?

Was a conquering male-godded people the start of it all? Is that why the West has followed a murdering course? Or did the West just get lucky, get started earlier?

The Mongols, people of the steppes, a conquering tribe, took armies through half the world; the Han Chinese did not, nor did they want to. The Spanish and other Europeans had steel in their hands and cruel hearts; the people they met in what we now call America were far less evil-minded. There are many tales along the Oregon Trail of how Original Americans were shocked at the behavior of the whites they met, even to each other (a post for another day).

We won’t answer all of these questions in this on-and-off series, but we’ll touch on them. We’re about to see new aggression against nations bordering the Pacific (the reason for studying Mahan and the “American century”), and we’ll see how it plays out. I hope, through our reading of Alfred McCoy, we’ll see context as well.