Yves here. Hubert Horan summarizes the state of play with Uber after 2024.

By Hubert Horan, who has 40 years of experience in the management and regulation of transportation companies (primarily airlines) and has been publishing analysis of Uber since 2016. Horan has no financial links with any urban car service industry competitors, investors or regulators, or any firms that work on behalf of industry participants.

Uber and Lyft both reported full year GAAP profits for 2024. Both companies reported their 2024 financials earlier this month. After correcting the results for known issues, this paper will explain how Uber achieved an $8 billion P&L improvement after losing $33 billion in its first 13 years. It will also discuss the huge divergence in Uber/Lyft stock performance, and why neither stock improved after releasing strong 2024 P&L results. It will also cover why autonomous vehicles—a business both companies abandoned—have once again become a major focus.

Uber Is Earning Small Profits but Continues to Mislead Investors About its Financial Performance

Uber had an operating profit of $2.8 billion and an operating margin of 6.4% in 2024. This was up from $1.1 billion (3.0%) in 2023, the first year Uber ever reported profits. It reported a 2024 net profit of $9.8 billion (22.4% margin; up from $1.9 billion (5.1%) in 2023) but, as will be discussed below, badly misrepresents the actual 2024 performance of its ongoing operations

As this series has documented, Uber includes multi-billion dollar items in its quarterly/annual operating results that have nothing to do with the current performance of ongoing business operations, and makes no effort to lay out the actual P&L of ongoing operations.

Uber’s most dubious practice is including its estimate of the changes of value in untradeable securities it received after shutting down operations that had been hopelessly unprofitable These include shares in larger companies that had driven Uber out of the market (Didi in China, Yandex in Russia, Grab in Southeast Asia) and in Aurora, which acquired Uber’s failed autonomous vehicle development efforts. This practice dates to its IPO prospectus, when it used the alleged appreciation of untradeable securities to inflate its bottom-line 2018 profitability by $5 billion, in the hope of creating the impression of robust, rapidly improving profitability. [1] Uber’s 2024 and 2023 “net profitability” were each inflated by $1.8 billion thanks to the claimed value of paper associated with discontinued operations.

$6.4 billion of Uber’s fourth quarter 2024 bottom line was due a tax valuation release. Thanks to Uber’s staggering 2010-23 losses (over $33 billion) it had deferred tax assets it could not report until there was some reasonably likelihood of positive income to offset. Uber claims it has over $41 billion in deferred tax assets, primarily from net operating losss carryforwards, research and development credits and from fixed and intangible assets where the tax basis exceeds book value.[2] Presumably Uber’s 4Q 24 $6.4 billion claim accords with IRS regulations.

The issue is how investors are supposed to interpret Uber’s 2024 P&L. Its SEC filings include a one sentence footnote mentioning the tax valuation release but do not explain where it came from, what specific events triggered the 4Q 24 claim, why it was $6.4 billion, or whether investors should expect similar tax asset impacts in the future.

And while Uber could not report the $6.4 billion until specific criteria had been met, it obviously has nothing to do with Uber’s 4Q 24 business performance. Uber faced a similar problem when it recorded $5 billion in stock based compensation expense as a 2Q 19 event, even though it covered work performed over multiple years. Then, as now, Uber’s published financials made no attempt to isolate these items so investors could not determine the true P&L results for current periods.

The graph above illustrates the gap between Uber’s reported net profit margin, and a net margin corrected to only include items related to its ongoing business operations during the reported time period. Uber overstated current P&L performance by 18 points in 2024 and 5 points in 2023, and overtime Uber rendered GAAP net profitability meaningless for any investor that was trying to track profit improvement over time. Even when Uber was producing massive losses its P&L did not have the huge volatility that its reported numbers suggested.

Uber produced meaningless GAAP net profit numbers because they wanted investors and other outsiders to focus on its even more bogus “Adjusted EBITDA Profitability” metric, which measures neither EBITDA nor profitability.[3] Since 2019 Uber has excluded over $21 billion of expenses from this “EBITDA Profitability” metric other than interest, taxes, depreciation and amortization.

This practice allows Uber PR to claim a “profit margin” 10-12 points higher than its corrected GAAP net margin in the last three years. Prior to the pandemic when Uber was desperate to mask how far the company was from GAAP breakeven it was claiming a profit margin 24-32 points higher.

This PR strategy has been successful. Media and financial analyst reports almost exclusively evaluate Uber profitability based on the bogus “Adjusted EBITDA Profitability” and only mention reported GAAP net profits in passing.

Additionally, Uber’s SEC reporting is designed to make it impossible for outsiders to determine what drove observed changes to bottom line results. Uber only publishes a single demand metric (“trips”) making it impossible to determine the relative growth rates by product (car services and food delivery) or geographic markets or to determine how unit costs and unit revenues have changed. This measure does not distinguish between a 10 block trip and a 50 mile trip.

Uber also makes it very difficult to evaluate changes in how gross customer payments are split between Uber and its drivers. A first approximation of driver revenue can be gleaned by subtracting “Uber Revenue” from “Gross Revenue” but most driver bonuses and incentive payments are buried within Uber’s “Cost of Revenue” and “Sales and Marketing” expense lines. Uber also never isolated expenses related to potential future lines of business (e.g. autonomous vehicles, freight, flying cars) so one could not accurately identify the cost of its current operations.

While Miniscule, 2024 Saw Lyft’s First-Ever Reported Profit.

Lyft had a small operating loss ($112 million, negative 2% margin) in 2024 but eked out a $22 million net profit (0% margin). This was a notable year-over-year improvement. It had a negative 8% operating margin and a negative 12% margin in 2023.

Lyft’s SEC reporting is less opaque than Uber’s, and car services are its only business. The overwhelmingly biggest factor driving its year-over-year P&L improvement was that it managed to increase its share of gross customer payments from 32% to 36%. This was a labor to capital wealth transfer of $634 million. Lyft’s revenue per trip increased by 12% while gross driver receipts per trip fell by 6%. As will be discussed below Lyft’s 2024 improvements mimic gains Uber achieved in 2022. Had this “take rate” not improved, Lyft would have lost twice as much money as they did in 2023 and had a negative 12% net margin

Lyft conducted a major cost reduction program in late 2022, and 2023 costs per ride fell 26%. But these impacts seem to have dissipated as 2024 unit costs increased by 4%.

Three Major Changes Drove Uber’s $8 Billion Annual 2019-2024 Profit Turnaround

As discussed above, reported net earnings are useless for analyzing how Uber’s performance has changed over time due and must be corrected to eliminate major distortions (which significantly inflated net earnings in 2018,21,23 and 24 and depressed them somewhat in 2022 and 22) and accounting timing problems (which badly understated 2019 earnings and significantly overstated 2024 earnings).

The corrected numbers show that Uber was losing $5-6 billion a year (negative 43-47 margin) before the pandemic. It then achieved a $4 billion improvement by 2022 (nearly 40 margin points) when it lost $2 billion (negative 6% margin) and then achieved further $2 billion improvements (5-7 margin points) in both 2023 and 2024.

| ($ billions) | 2018 | 2019 | 2022 | 2023 | 2024 | |

| Reported Net Income [4] | ($4,033) | $997 | ($496) | ($9,142) | $1,887 | |

| Reported Net Margin | 9% | (60%) | (29%) | 5% | 22% | |

| After eliminating discontinued ops and Timing issues | ||||||

| Corrected Oper Income | (3,424) | (6,115) | (1,832) | 1,110 | 2,799 | |

| Corrected Oper Margin | (30%) | (43%) | (6%) | 3% | 6% | |

| Corrected Net Income | (5,338) | (6,025) | (1,929) | 73 | 2,022 | |

| Corrected Net Margin | (47%) | (43%) | (6%) | 0% | 5% |

Three major factors appear to have driven these improvements: Uber has been keeping a larger share of each passenger dollar (and giving drivers less), it eliminated major corporate costs during the pandemic, and developed more sophisticated price discrimination tools allowing it to charge higher fares to customers more likely to accept them and to reduce compensation offers to the minimum they thought specific drivers would accept.

Uber increased its reported “take rate” from 22% of each dollar of customer payments in 2018-19 to 28% since 2022. In 2024 its ridesharing take rate exceeded 30%. Uber reduced the driver share of gross revenue from 78% to 72%. Most of this wealth transfer occurred in 2022, when Uber revenue increased (and driver revenues decreased) by $6.5 billion. If the take rate had remained at 22% Uber’s corrected net loss in 2022 would have been $8.5 billion with a negative 34% net margin. This value increased to $8 billion in 2024, given growth in trip volumes. Perhaps more detailed data could produce a more precise measure of Uber/driver revenue shares but Uber is unwilling to share that data.

As the earliest pieces in this series explained, car services face major structural problems that limit service quality and efficiency, such as extreme demand peaking and empty backhauls. With pre-Uber traditional taxis these costs were effectively shared between drivers and car owners. Uber’s business model did not reduce any of these costs, it simply shifted all of them onto the shoulders of the drivers.

During the pandemic Uber also eliminated marginal operations and many expenses not directly related to current car or food delivery services. Prior to the pandemic Uber flooded cities with capacity at low fares as it pursued market dominance and very high growth rates.

But due to empty backhauls, demand peaking and other issues much of this capacity was especially unprofitable, and Uber made big cuts. Again, Uber is unwilling to share data that would allow outsiders to calculate unit cost and utilization/productivity changes.

Even when corrected for discontinued operations and timing issues, the simple ratio of total Uber expenses per trip is 24% higher in 2024 than it was in 2019 even though trip volumes increased 63%, and Uber eliminated major tranches of unproductive costs (e.g. autonomous vehicle development, low margin trips).

One plausible guess is that this cost cutting (which should have been largely exhausted by 2022) reduced losses by roughly 10 margin points, based on the comparison of actual 2019 margins (negative 43%) and the negative 34% 2022 margins that would have been seen if Uber’s take rate had remained at the 2019 22% level.

Uber’s algorithmic pricing and driver payment practices replaced pre-pandemic systems where these were linked to trip time and distance and drivers could see the relationship of their payment to what the passenger had paid. Uber now puts payment offers for rides out to drivers, who if they fail to accept low offers run the risk of failing to meet utilization targets and being locked out of the system.

While there is abundant anecdotal evidence from drivers about how this has depressed their earnings there is no way to estimate the impacts on Uber’s P&L or aggregate driver compensation, and Uber is especially zealous about hiding the effects from drivers and investors. It presumably helped drive Uber’s ridesharing take rate increase (27% to 30%) between 2022 and 2024, which was worth over $2.5 billion annually.

Uber Could Not Have Achieved Profitability Without Massive Anti-Competitive Market Power

Looking at the bigger picture, the real driver of Uber’s profit turnaround is that it has achieved large and sustainable levels of anti-competitive market power.

Uber is totally immune from any threat of discipline from either marketplace competition or laws or regulations established by democratically elected governments designed to protect general public interests or the specific interests of consumers or workers. With that unconstrained market power, Uber has been able to raise fares with impunity and impose algorithmic pricing systems because passengers will never see competitive offerings and will have no legal/regulatory protections against discriminatory or deceptive pricing practices.

Uber has thus been able to transfer billions from drivers into its own pockets, since no competitor will offer better terms, and Uber can overwhelm any judicial or legislative efforts to enforce minimum standards. Without that unconstrained market power, Uber would still be losing billions every year, and would have no plausible path to breakeven.

Three major factors, working in combination, created and will continue to sustain this anti-competitive market power. The first was that Uber demonstrated a willingness to employ predatory pricing to a level that would have made Rockefeller and Carnegie blush. The investors who controlled Uber were always totally focused on achieving quasi-monopoly power because this was the only way they could ever achieve returns on the $13 billion they had invested. Even when Uber was losing $6 billion a year and enduring scandals and bad publicity it was universally understood that Uber would use its massive cash position to crush any potential competitive challenge. This barrier to entry became even more impregnable once Uber achieved positive cash flow.

The second factor was Uber’s willingness to employ scorched earth techniques to crush any attempt to place any external constraints on its market power. Uber effectively achieved total deregulation of urban car services totally outside the democratic processes that established public oversight.

To cite one of many examples, when the California Supreme Court established rules for determining when outside contractors were truly independent and thus were not entitled to employee labor law protections, and the California legislature codified these rules into law, Uber led a $200 million effort known as Proposition 22 to overturn them. Uber outspent supporters of the independent contractor legislation by a 10:1 margin and falsely claimed that a big majority of Uber drivers opposed the rules. But by crushing the California judiciary and legislature Uber achieved the power that made the $6 billion in annual labor to capital wealth transfers that drove its path to breakeven possible. [4] The stock market, which fully understood the importance of using market power to suppress driver compensation to the lowest level possible, immediately raised the market capitalization of Uber by $36 billion (over 60%) even though passenger payments were still covering less than 70% of Uber’s actual costs.

The third factor was Uber’s extraordinary narrative development/promulgation skills, which hugely contributed to the first two factors. Unlike most “tech” startups at that time, Uber made spending on PR and lobby a top corporate priority from day one. Its original messaging, copied directly from longstanding libertarian efforts, blamed all of the problems of traditional taxis on corrupt regulators. Since anyone concerned about consumers, workers or the efficient operation of urban transport infrastructure was corrupt and evil, the capital accumulators how had invested in Uber should be given the “freedom” to do whatever they thought might maximize their investment returns.

This narrative positioned Uber as a heroic disruptor, whose innovative technology could solve all of the problems that had plagued urban car services for a hundred years. Even though urban transport had never attracted the interest of capital markets, Uber claimed it would soon achieve Amazon-like meteoric demand and valuation growth. None of these claims about industry problems and solutions were backed with any supporting evidence and Uber’s PR narratives remained powerful even after it accumulated $33 billion in losses, and even after its post-pandemic fares have proven to be much higher than the traditional taxis they “disrupted” had charged. [5]

Uber’s narrative/PR power also rendered the mainstream and business media pliant. They meekly accept Uber’s preferred framings (regulators were corrupt, drivers didn’t want legal protections, Adjusted EBITDA is a legitimate measure of profit), make no effort to investigate service, pricing and working condition changes, to explain why Uber lost $33 billion or how it achieved $8 billion in profit improvement.

Uber illustrates the magnitude of damage the rest of society can suffer when capital accumulators can destroy market competition. A handful of Uber investors and executives have become fabulously wealthy. But they destroyed a functioning taxi industry (and the capital and workers it employed) and replaced it with car service that is more limited and higher cost while reducing wages and job security. Transit systems (and the taxpayers funding them) suffered major losses thanks to traffic diverted by Uber’s predatory uneconomical fares. Traditional taxis were resilient but Uber and Lyft will be free to ignore any marketplace forces they might find inconvenient.

Uber, Lyft stock prices have been behaving quite differently since mid-2022

Like the other “tech unicorns” of the past couple decades, Uber and Lyft were never designed along Finance 101 lines where they would attract investors with business plans that demonstrated strong likelihood of future profits, and where share prices reflected the market’s judgement about the stream of risk-adjusted future profits.

Capital markets had become fixated on the possibility that selected companies could become super high flyers, producing meteoric demand growth and equity appreciation, making its founders and early investors stratospherically wealthy. Financial analysts and journalists paid almost no attention to the specific business model of startups like Uber and Lyft or the industry they were seeking to enter, or to whether their economics were like previously successful unicorns (Google, Facebook, Amazon, et.al.) or whether early results demonstrated they were on track to deliver on their promises. The emphasis was totally on narrative, buzzwords (disruption, platforms, innovation, etc.) and the personalities of the top executives and venture capital investors.

Both Uber and Lyft went public in the first half of 2019, with (as this series documented) IPO prospectuses that documented huge losses and provided no credible evidence of sustainable profits in the future. Uber’s prospectus highlighted that it expected to become the “Amazon of Transportation”, that its investment in autonomous cars would fuel long-term growth and that investors’ expectations about the future should recognize that it currently served less than 1% of its “addressable market” (global trips within urban areas). The two IPOs created $80 billion in corporate value ($65 bn Uber, $15 bn Lyft) although they had been seeking $150 billion ($120 bn Uber, $30 bn Lyft). [6]

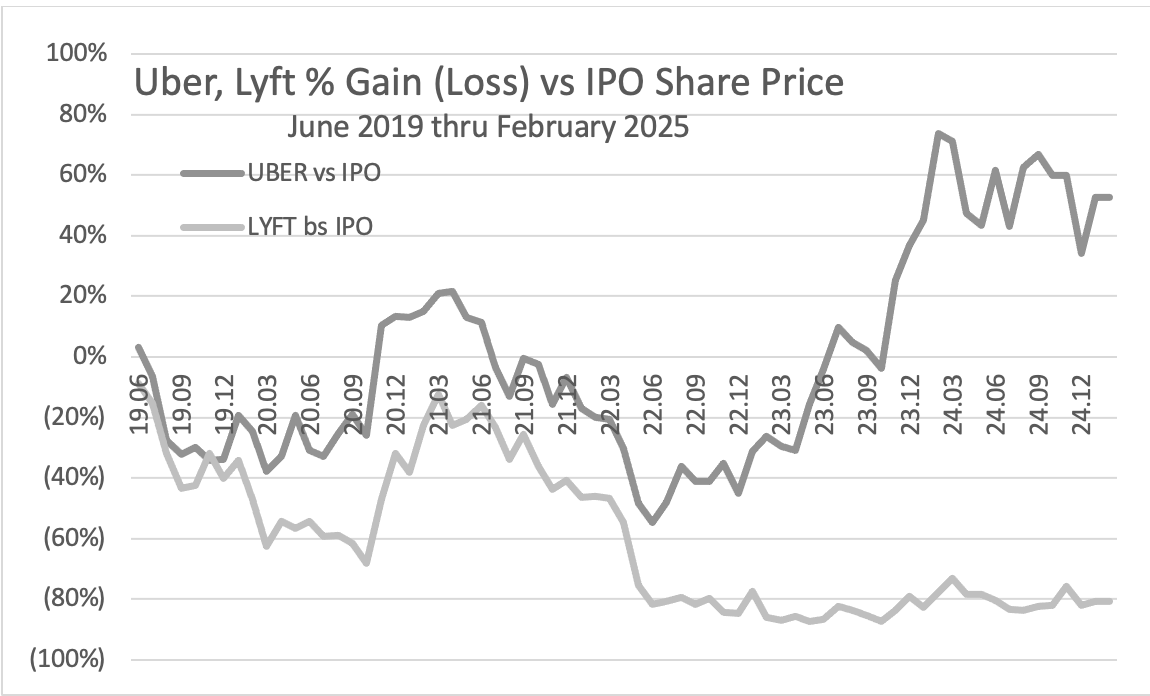

As the two graphs below illustrate the stock prices of Uber and Lyft quickly fell below their IPO levels and failed to appreciate in line with general “tech” indices. Oddly, the huge pandemic demand collapse did not have a major impact on either stock. Until mid-2022 Uber stock clearly did a bit better than Lyft’s although they roughly tracked each other, including serious declines in 2021-22. But in mid-2022 the paths of the two stocks dramatically diverged.

Lyft, which had been trading roughly 20% below its IPO price ($72) in 2021 fell to roughly 80% below in mid-2022 and has remained at that level ever since. The mid-2022 equity collapse coincides with major declines across a wide range of so-called disruptive tech-based startup stocks as investors appeared to be growing tired of companies who were burning cash in pursuit of rapid growth but did not have a clear path to sustainable profitability. These companies lived in what one observer called “the enchanted forest of the unicorns” where your valuation is whatever you say it is and received little serious scrutiny when they went public and only avoided collapse because of investors “consensual hallucination” (and low interest rates). The major restructuring efforts Lyft announced in the 2nd quarter of 2023, the recovery of pandemic traffic declines and its subsequent reduction in losses have had had little impact on its share price. [7]

Uber equity began appreciating again just at the point when Lyft equity fell to its lowest levels, triggered by Uber’s big $36 billion gain following its Proposition 22 victory over the California judicial and legislative efforts to prevent the misclassification of many drivers as independent contractors.

Between mid-2022 and early 2024 Uber’s appreciation roughly tracked broad indices of “tech” stocks, although with a larger gap then was seen following its IPO. Uber’s share price has fluctuated between a 40% and 60% premium over its IPO price for the past five quarters. [8]

Wall Street clearly celebrates companies who can use artificial market power to suppress wages, but Uber’s California triumph cannot explain why Uber stock began appreciating in line with “tech” indices while Lyft remained in the doldrums. Both companies employ the exact same ridesharing business model, and Lyft received the same Proposition 22 benefits that Uber did.

It is perhaps useful to see Uber as a “memestock”—not in the sense of companies like GameStop or AMC who saw huge valuation changes purely due to viral social media posts, but along the lines of dot-com stocks and other major market fads. Thanks to its powerful PR/propaganda messaging over the years, Uber convinced many that it was a high-growth “tech” stock like Amazon, with years of profitable Amazon-like expansion into new businesses. Uber was never seen as risky as Lyft and the many other smaller “tech” companies now trading at a fraction of their IPO prices. To some extent Uber’s ruthless, predatory behavior may have created the image of a 900 pound gorilla impervious to normal economic laws not dissimilar to corporate behemoths like Amazon.

Uber equity value continues to depend on the widespread impression that it is still a high-flying growth stock, which cannot be explained in objective financial terms. A share price above IPO levels and growing steadily implies that investors believe that Uber will enjoy years of robust demand and profit growth, and Lyft will not.

While the high-flying growth image certainly helps senior executives achieve bonuses based on stock price increases, those executives will face a major challenge producing the rapid, profitable growth investors are hoping for. Most things Uber could do to boost growth (lower prices, more capacity) would be unprofitable and would reverse its post-pandemic efficiency gains. The things Uber has been doing to increase margins (reduce capacity, raise fares, squeeze drivers, eliminate speculative spending on new businesses) would cut growth. Uber’s stock price has never been sensitive to incremental P&L improvements did not meaningfully respond when it actually achieved its first profits in 2023-24.

Despite the seemingly positive P&L numbers, the stocks of both Uber and Lyft both fell (7% and 5% respectively) after their 2024 financial reports. Press reports blamed both on weaker-than-expected demand forecasts for the balance of the year, illustrating the importance of growth expectations. [9] Analyst questions to the CEOs ignored issues like the risks of Uber-Lyft price wars, or where Uber’s $6 billion tax credit came from and focused instead on how they would realize the growth potential of autonomous vehicles, a previous market fad that both companies had abandoned but now appears to have come back to life.

Both CEO’s made general claims about how could provide a wonderful platform for any future AV operators, while sidestepping the questions of how a future AV industry might actually develop. This strategy assumes the ridesharing companies could establish a quasi-monopoly middleman position in the future AV industrty (akin to Google’s dominance of search or Facebook’s social media position) when no other urban transport companies see it as a useful middleman. [10] Uber and Lyft have survived because they can impose whatever terms and conditions they want on their fragmented, subservient drivers. Working with the owners of multi-billion dollar AV fleets (including companies as large as Tesla and Waymo) might pose more difficult challenges.

______

[1] “Can Uber Ever Deliver? Part Nineteen: Uber’s IPO Prospectus Overstates Its 2018 Profit Improvement by $5 Billion” Naked Capitalism, April 15, 2019, A similar $3.2 billion overstatement of 2021 performance was discussed in Can Uber Ever Deliver? Part Twenty-Nine: Despite Massive Price Increases Uber Losses Top $31 Billion, Naked Capitalism February 11, 2022.

[2] Hinde Group, Uber’s Tax Attributes Are Worth Billions, June 2023

[3] “Adjusted EBITDA Profitability” excludes Uber’s huge stock-based compensation expenses. “Segment Adjusted EBITDA Profitability” which Uber press releases emphasize when discussing the separate performance of car services and food delivery also excels billions in IT, legal, lobbying and other expenses that cannot be directly linked to specific customer requests.

[4} The campaign against the legislative protections for independent contractors, known as Proposition 22, was orchestrated by Uber chief counsel Tony West, who also led Uber’s efforts to cover up attacks on a woman who had been raped by an Uber driver, and the Obama Department of Justice’s refusal to prosecute any financial institutions for their role in the 2008 economic collapse, and ensured that Kamal Harris’ presidential campaign was dedicated to the interest of tech oligarchs. Can Uber Ever Deliver? Part Thirty-Four: Tony West’s Uber Legacy and the Kamala Harris Campaign, Naked Capitalism, February 5, 2025

[5] This series has long claimed that Uber’s propaganda based narrative construction/promulgation skills were its only real competitive advantage, and that its only real “innovation” was adopting longstanding partisan political propaganda techniques to a corporate developms