Mr. Market was not much impressed with Trump’s pep rally in the form of his address to a Joint Session of Congress. And as the tone of commentary is turning decidedly downbeat, which is also leading to renewed concern about leverage and credit crunch/crisis risk. We’ll turn in due course to a Wall Street Journal article, They Crashed the Economy in 2008. Now They’re Back and Bigger Than Ever, about the expectation of a big uptick in structured credit deals in 2025.

We’ll explain the critical gap in the piece, that the sort of structured credit showcased in this piece isn’t what caused the crisis, and the piece is not inquisitive about the real issue….why the boomlet? What might be driving this froth?

We’ll also briefly look at some of the other of debt discussed recently as potentially crisis-inducting, and finally cover the one that strikes us as much more dangerous: lending to private equity-owned companies. It has many of the key features, such as leverage on leverage and opacity, which were key to the 2008 crisis became as severe as it was.

Note that the Journal story assumes that projected structured credit volumes for 2025 pan out. It may also be that big uptick in enthusiasm for structured credit was a Trump trade, and they are fading fast.

Some of the dour financial media headlines over the last two days:

US stocks sink on tech weakness and tariff confusion Financial Times

Trump’s Golden Age Begins With a Brutal Trade War Wall Street Journal

‘It’s like a whipsaw’: Donald Trump’s tariff U-turns unnerve businesses and investors Financial Times

The Recession Trade Is Back on Wall Street Wall Street Journal. Lead story Thursday.

Dow futures drop 400 points as selling returns to Wall Street on Trump tariff confusion: Live updates CNBC. As of 6:45 AM EST

US stocks struggle as ‘America First’ bets backfire Financial Times

Is the White House trying to engineer a recession? This Wall Street pro explains the vision. MarketWatch

Global bond sell-off deepens as Germany jolts markets Financial Times. Note the swoon is the result of a big German spending package, which the article oddly does not mention is to a fair degree due to Trump-driven armament plans. US equity future are trading down on this development.

As we indicated, the only way Trump’s economic policies make sense, if you rule out his extreme need to dominate and cognitive capture by strong form libertarian crackpottery, is that he intends rerun a Russia-in-the-1990s economic train wreck so as to facilitate squillionaire asset grabs. His fondness of announcing alarming overkill measures, some of which he partly retreats from as Mr. Market has a hissy, and his aggressive Federal bureaucracy breaking (some of which is being checked by courts, some of which is being quietly reversed due to excessive collateral damage) are producing a tremendous amount of uncertainty. Trump clearly loves uncertainty since it gives him maximum operating room. But businesses and consumer, unless they are financial speculators, do not. They tend to curb spending and investment out of an entirely rational fear of new downside risk.

Even before the enthusiasm for Trump’s economic policies started going into reverse, many experts and even laypeople were concerned about high debt levels, so again, a sudden demand for structured credit at this juncture in the cycle seems mighty odd. Remember that the underlying assets in a structured credit deal could just as easily be used as collateral for a plain vanilla bond or loans. There is a multi-decade history of exotic-seeming assets serving in that role, from David Bowie’s catalogue to high end art serving as security for loans. The big reason for securitization, in this blogger’s humble opinion, is to create more AAA rated paper. The AAA tranches in most securitizations account for 70% to 80% of face value. And the reason for the increase in demand of that, at least in the pre-crisis period, was to secure derivatives positions. From ECONNED:

Some have argued that the parabolic increase in demand for repos was due in large measure to borrowing by hedge funds. Indeed, Alan Greenspan reportedly used repos as a proxy for the leverage used by hedge funds.16 Others believe that the greater need for repos resulted from the growth in derivatives. But since hedge funds are also significant derivatives counterparties, the two uses are related.

Brokers and traders often need to post collateral for derivatives as a way of assuring performance on derivatives contracts. Hedge funds must typically put up an amount equal to the current market value of the contract, while large dealers generally have to post collateral only above a threshold level. Con- tracts may also call for extra collateral to be provided if specified events occur, like a downgrade to their own ratings.17 (Recall that it was ratings downgrades that led AIG to have to post collateral, which was the proximate cause of its bailout.) Cash is the most important form of collateral.18 Repos can be used to raise cash. Many counterparties also allow securities eligible for repo to serve as collateral.

Due to the strength of this demand, as early as 2001, there was evidence of a shortage of collateral. The Bank for International Settlements warned that the scarcity was likely to result in “appreciable substitution into collateral having relatively higher issuer and liquidity risk.”

That is code for “dealers will probably start accepting lower-quality collateral for repos.” And they did, with that collateral including complex securitized products that banks were obligingly creating.

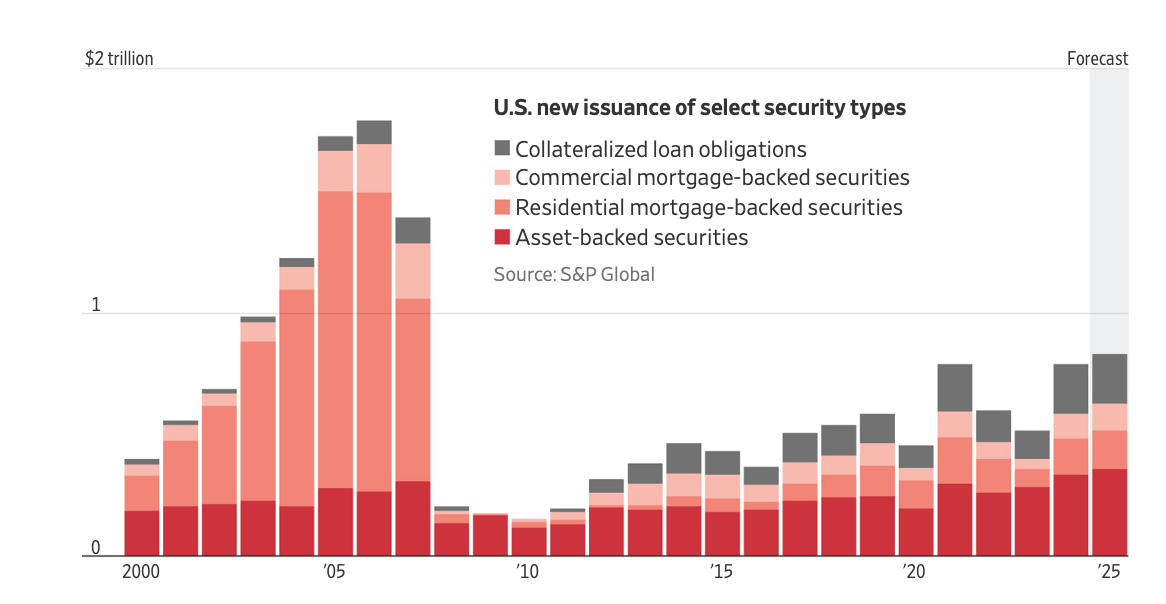

Keep in mind GDP is now 2x as large as before the crisis, so in relative terms, the projected amount of structured credit issuance is still not as large as right before the crisis. But that 2025 jump is striking.

We were too polite back then. Another way to tell the story is “Greenspan’s ‘Let a thousand flowers bloom’ approach to derivatives led to a kudzu-like proliferation and excessive risk-taking.

Mind you, yours truly has no idea what is producing the demand surge the structured credit industry anticipates (which as indicated may not materialize given the Trump-induced market tsuiris). But the Journal story does not explain what is generating this pattern:

Mind you, I am not a fan of unnecessary complexity, since it enables structurers to pull out more fees than for plain vanilla products, can support the general tendency towards overdiversification as a bizarre counter to a fondness for unduly tailored exposures (basically fund manager busywork which again adds to false perceptions of value added and too many fees), and is often useful in getting chumps to eat too much risk for too little return.

But press commentary seldom addresses the big system-wide drag of fostering yet more unproductive financialization. Instead they focus on the public’s hot buttons and in the process, often help perpetuate financial services industry information fogging.

As much as readers might not like hearing it, most of the structured credit products in the chart above were tested in the crisis and got through unscathed, such as collateralized loan obligations (a pretty conservative structure) and commercial real estate MBS (which unlike subprime, have loans big enough that services can work out if they go back, and thus servicers are paid to do modifications).

By contrast, subprime mortgage backed securities had always been trouble. There had been a much smaller subprime market in the 1990s which hit the wall for essentially the same reasons as the 2000s versions. The structured paper didn’t pay enough to cover the risks and provide enough in fees to the intermediaries for putting them together to sell them. The “solution” had been to shortchange the lowest rated tranche, the BBB/BBB- tranche, in terms of yield and other protections. That was only a small part of the total face value, 3% to 4%. But there weren’t enough stuffees for this paper. So like making sausage out of less desired pig bits, they were rolled into CDOs, with enough better-looking assets to make them minimally appetizing. Again, the top tranche of CDOs was rated AAA but traded at more like AA yields (as in investors recognized the AAA ratings were a stretch).

Confirming this view, a careful paper by central bank connected economists (who had to have harbored no love for subprime) contained the finding that the authors found surprising: that the AAA and other high rated tranches of subprime mortgage securitization had performed well. It was the lower rated tranches where the defects lay.

So to truncate a much fuller telling of this tale, the problem was not asset backed securities per se but picking assets to securitize in bulk that were really not well suited to the exercise, and then “solving” that problem with a leverage-on-leverage scheme, the asset-backed-securities CDO, colloquially called the subprime CDO. Leverage on leverage on any scale is a ticking time bomb. Similarly highly leveraged trust of trusts (and trusts of trusts of trust) precipitated the Great Crash of 1929. For more detail on the critical role of credit default swaps and how subprime shorts created them in bulk using CDOs, driving demand to the very worst mortgages, see this post.

Please note we are looking past the the massive problem, which we discussed at excruciating length back in the day, that residential mortgage securitizations pay servicers to foreclose, not to modify mortgages, which (in unduly simplified terms) gave them incentives to foreclose, while back in the day when banks retained the mortgages they originated, they had incentives to modify mortgage. The evidence it that modifications minimize lender/investor losses, but the servicers were not paid to harbor such tender concerns.

Now perhaps some of these structured credit products have had their features tweaked to make them more hazardous over time. But we hear nothing of the kind from the Journal. It instead showcases the giddy mood at SFVegas, annual structured-finance conference. For instance:

The convention halls at the Aria Resort & Casino on the Las Vegas Strip were packed for four days this past week with bankers and their clients, in uniforms of Italian sportscoats and office sneakers. They fist bumped greetings as they strode to their next meetings, giving off the feel of a joyous reunion.

The hotel’s sky suites were booked. Citigroup bankers set up more than 900 meetings. A panel on data centers was so popular, attendees sat on the floor…The last time it boomed like this was 2006 and 2007. Mortgage bonds were selling like crazy, and this crowd was flying high.

We don’t hear much about the presumed investor demand:

Today, big investors want to buy these types of securities because they think they are relatively safe and yield more than government-backed bonds. Banks are mostly middlemen because regulations instituted after 2008 curtailed their lending. That has opened the way for giant fund-management companies like KKR, Apollo Global Management and Ares Management to muscle in and make loans with their own capital…

Sales of securitized debt have been surging since the Covid-19 pandemic, when the Fed lowered rates and investors were awash with cash and looking for investments, Flanagan said. “Everything is going to end up here,” he said.

This section is misleading. KKR, Apollo and Ares have indeed moved in on bank syndication of corporate loans, aka leveraged loans. They often do wind up in collateralized loan obligations, which as mentioned, is a conservative structure. Apollo and Ares are also big commercial real estate players, so they could also be intermediating commercial real estate debt. As you will see below, office space is only one type in a much bigger commercial mortgage business.

Now mind you. we DO think private equity related lending is going to cause a world of hurt. And there is leverage on leverage, to the degree outsiders can’t determine the total debt burden of PE funds and their holdings. That does NOT indict CLOs. That DOES indict investors tolerating private equity barons using too many ruses to load more debt onto their funds, not just on the companies they bought….but even the unspent capital commitments of the investors!

The “too much cash looking for a home” is a weak echo of the “wall of liquidity” of the runup to the crisis. Then, every credit product was underpriced relative to the risk. We don’t seem to be there yet, but the structured credit confab could be a warning sign. But in 2007-2008, we were later able to unpack why. Derivatives and other leverage-on-leverage (later called the shadow banking system) were big drivers.

Other Candidates for the Next Credit Unwind

Keep in mind that a sovereign currency issuer like the US can never become insolvent; we can always create more dollars. A sovereign currency issuer can generate too much inflation, particularly if its government spending either does not go much at all towards or is very inefficient about increasing productive capacity.

Financial crises result from excessive private sector debt. A partial listing of worries:

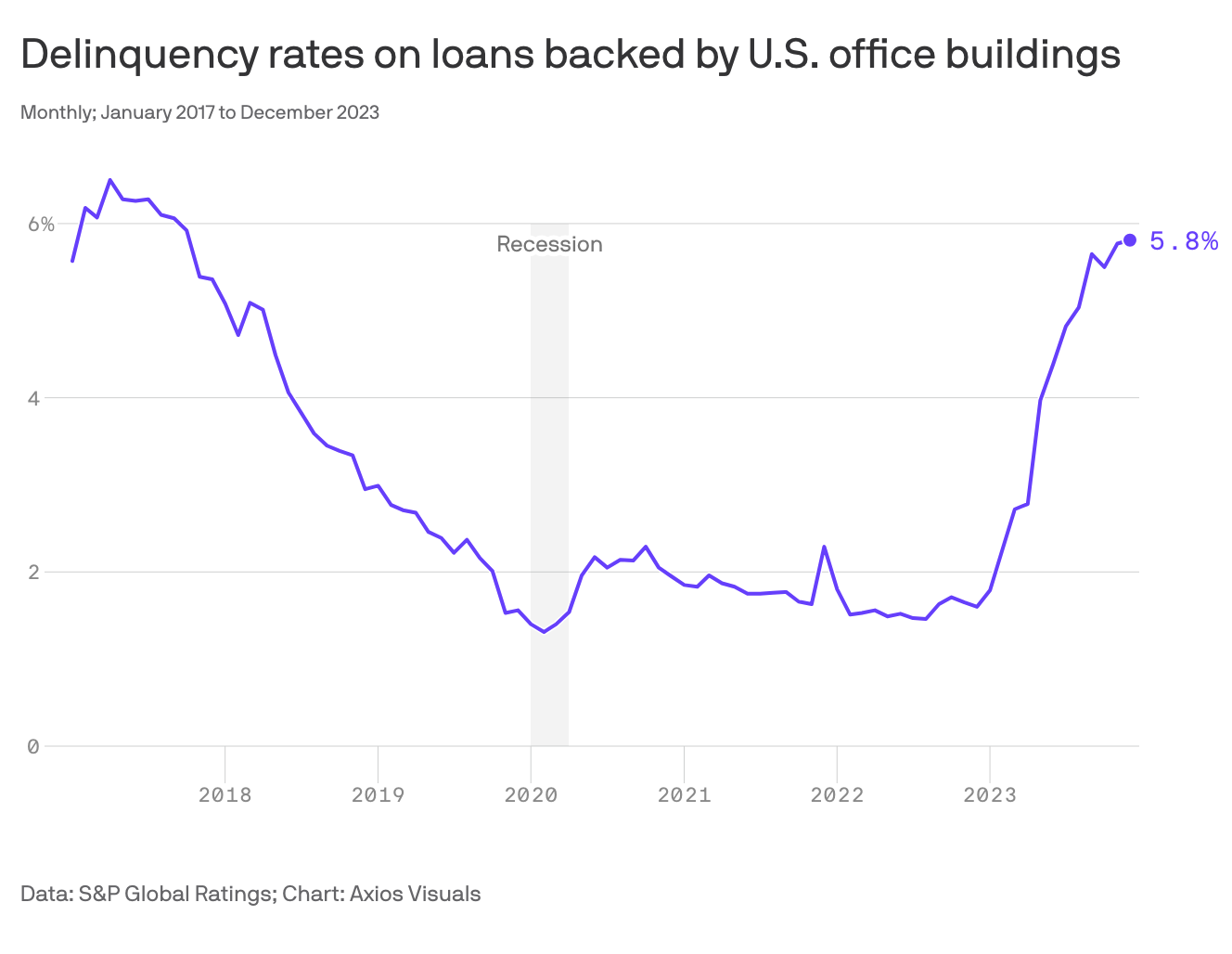

Loans to commercial office space. Total office debt was $920 billion as of October 2023, versus (depending on if you counted Alt-As) subprime debt of $1.3 to $2.0 trillion before the crisis. And recall, as we explained long form in ECONNED, that the US housing market bubble was not big enough to cause a near global financial system failure (for a short version, see here). CDOs made substantially of credit default swaps created 4-6 times the exposure of the riskiest rated tranches of mortgage bonds and concentrated these exposures at highly leveraged, systemically important financial institutions. The 2008 meltdown was a derivatives crisis, not a mortgage crisis.

Having said that, commercial mortgage unwinds have produced serious regional downturns and intensified recessions. The particularly nasty but short 1991-1992 recession is generally described as the result of the S&L crisis, but its severity diverted attention from another meltdown, that of LBO loans. Oh, and remember that Citigroup needed to be rescued? One of its big sins was having made a lot of junior mortgages to commercial development projects in the oil patch that turned out to be “see through” buildings (as in no tenants).

Nevertheless, the office picture is not pretty. The first chart from Axios is a bit dated (to year end 2023) but you can see the trend:

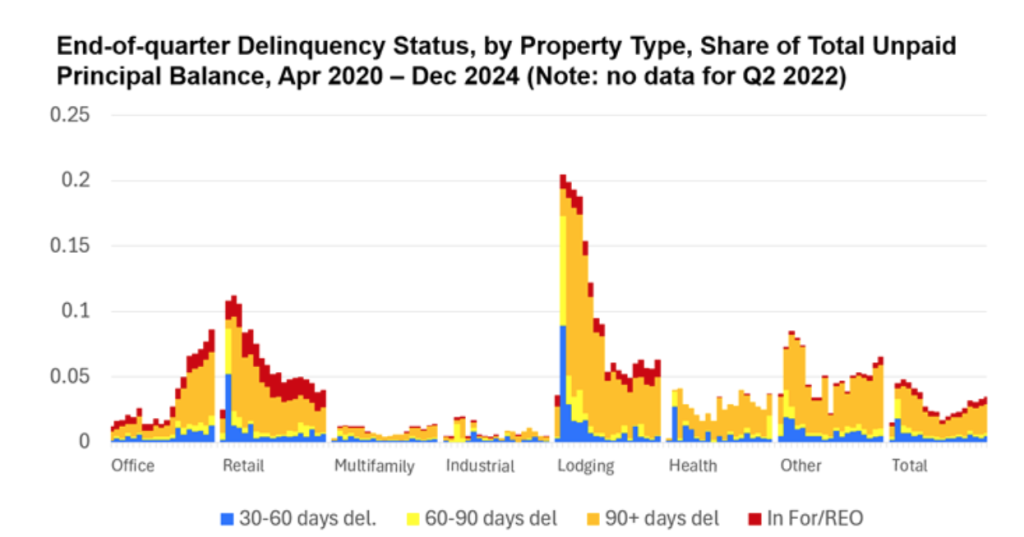

This one, from the Mortgage Banker’s Association through year end 2024, shows the office mortgage picture has only worsened. The itty bitty scaling winds up underplaying the severity of the situation:

And the raw delinquency level isn’t the whole story. Aside from serious knock-on effects, such as to municipal budgets, the damage to lenders is set to be larger than “normal” due to the persistence of work from home resulting in lower recoveries on foreclosures and workouts. Some properties will not be salvageable, particularly so-called B and C office space.

Emerging economy debt. Former UN economist Jomo Kwame Sundaram has been warning for well over a year of the parlous state of many emerging economies and how Western policies are making matters worse and thus increasing the odds of a crisis. Keep in mind that if one decent-sized country gets in trouble, the odds of contagion are high because lenders and investors will cut back reflexively. Moreover, the IMF insistence that lenders be repaid in the Asian crisis led all the economies in the region, including China (which did not take an IMF “program” but could see what was happening) to adopt even more aggressive trade surplus policies so as to accumulate a war chest of foreign exchange reserves so they would not need to submit to the tender ministrations of the IMF again.

As we have pointed out repeatedly, BRICS in its Kazan Declaration reaffirmed the role of the IMF as the country-bailouter-in-chief. So there’s no kinder-gentler Global South rescue program in the offing if a weak country his the wall.

Vonfirming Jomo’s regular troubled updates, from the IMF in February:

Many emerging markets and developing economies face elevated debt vulnerabilities and financing needs. Following the 2020-21 surge in debt levels associated with the COVID-19 shock, and the subsequent tightening in global financial conditions, many emerging markets and developing economies (EMDEs)1 are grappling with rising debt service burdens that squeeze the space available for development spending. Pandemic-induced deficits have declined, and debt levels have stabilized and are projected to remain stable or slightly decline under staff’s baseline assumptions. However, many EMDEs are confronting high costs of financing, large external refinancing needs, and a decline in net external flows amid important investment and social spending needs.

Mind you, these conditions existed before the Trump tariff actions and impact on supply chains were on the radar. See this Bloomberg story released after the IMF study: Asian Currencies Face Renewed Headwinds as Tariff Fears Escalate. Weaker currencies mean more difficulty in servicing foreign currency debts. Even if the countries were smart and did not (much) go there, if there are no capital controls, odds are decent that some large companies did.1

Are US and Western institutions exposed? Perhaps plugged-in readers like Colonel Smithers will opine, but the short answer is that the assumption that they aren’t is often disproven by events. The reason Volcker relented sooner than he wanted in driving US interest rates to the moon is that Latin American crisis was threatening US banks. The early 1990s bailout of Mexico using the US Exchange Stabilization fund was actually a bailout of Morgan Stanley and some other derivatives fellow travelers. No one knew LTCM was systemic until it came unglued, the unwind accelerated by the Russian financial crisis of 1998.

Unlike the runup to the 2007-2008 crisis, US consumers look to be in not-bad shape, at least in terms of debt levels, as opposed to routine budget stress. Household debts, bankruptcies, foreclosures, credit card debt , and auto loans are all at tame levels. Obviously, sudden big job losses could change the story. But there’s no big worries here.

Private Equity Lending: Opacity and Leverage on Leverage

Given the length of this post, I am going to go light on burgeoning private equity borrowing, which we have been writing about for years, and refer readers to an excellent one-stop shopping piece from the Financial Times: How private equity tangled banks in a web of debts. It is hardly a secret that most private equity funds load up the companies they buy with a lot of debt. It is less well known that they increase what is called “operating leverage” by, when possible, sell company-owned real estate to third-party investors, with the value of the property reflecting the lease payments the company (often a retailer or hospital chain) now has to pay. Of course, the lease payments are set high to goose the sales price.

A third practice even less well known is subscription line borrowing, not at the level of the companies, but at the level of the fund, creating leverage on leverage. And what secures that? The remaining, unspent capital commitments of the investors! Note that it isn’t just private equity funds that use this subscription line financing. Private credit funds do too!

The Financial Times article hones in on a key question: how much are banks exposed? Recall that in the 2007-2008 crisis (to simplify a very long story) many of those nasty CDOs we discussed above wound up being owned by systemically important and highly leveraged banks, vitiating the myth that more elaborate risk-parsing and risk-selling would distribute it better….and importantly, away from the critical-to-commerce banks. From the story:

At the centre of this sprawling web of debt are some of the global financial system’s most critical institutions: banks. They now have multiple connections with the industry — including lending to buyout-owned companies, the funds that acquire them, the firms that manage them and the investors that back them.

As higher interest rates put pressure on borrowers, regulators are asking an important question: could the private equity industry pose a risk to the wider financial system?

The article has a very nice graphic showing where different types of borrowing occur. Importantly, it makes clear that banks and regulators have no idea what the total exposures are:

The only people with a birds-eye view of the total borrowing across a firm, its funds and their portfolio companies are the general partners.

“There should not be a pocket of the market that touches on so much of the economy in such a sizeable way, where we can say, oh there’s leverage, and then very few of us can explain what that leverage means and why it might — or might not — be risky”, said Victoria Ivashina, a professor at Harvard Business School specialising in private capital.

Different types of lending are led by different teams within a bank, and often different banks altogether. The lack of oversight has regulators worried about whether lenders can really know just how exposed they are.

The inability to get a good view of total exposures and where they lie is very reminiscent of the runup to the crisis, where even good reporters and an active econoblogosphere, with lots of subject matter experts, could not get to the bottom of it. This time around, we have even less transparency and inquiry.

And the private equity industry is now struggling to deliver returns, to the degree that assets under management are shrinking, which has not occurred since 2005. Thatwns the incentive to use overly aggressive borrowing to try to satisfy investors is even higher than ever. From the Financial Times yesterday:

Even during the 2008 financial crisis, the private equity industry recorded modest asset growth, underscoring the magnitude of the challenges currently facing buyout groups.

Fundraising has slowed sharply as private equity groups have struggled to sell assets and return cash to investors, causing large pension funds and endowments to retrench, said Hugh MacArthur, chair of Bain’s global private equity practice…

The lack of distributions has squeezed pension funds, which need regular cash payouts to fund their commitments to retired workers.

In 2024, the distributions from the private equity industry as a percentage of net assets fell to their lowest in more than a decade at just 11 per cent, Bain found.

Investors have responded by resisting new fund commitments…

“It won’t all be better in 2025,” MacArthur said. “It’s a three- or four-year problem.”

How ugly this gets is anyone’s guess. But as a friend often says, “If you want a happy ending, watch a Disney movie.”

______

1 A fresh whistling-past-the-graveyard article which looks intended to counter the IMF release in particular calls out the country where I am now as a reassuring indicator of the sound condition of emerging economies. This cheery take contrasts with detailed descriptions of why that ain’t so in the local media (this level of candor is unusual, suggesting it is an open secret locally; see another downbeat recent take) and reports from local bank connected colleagues.