It is also a major victory for Wall Street. But what could it mean for China’s trade relations with Latin America, in particular the US’ largest trade partner Mexico?

Midway through last week, as the economic reverberations from Trump’s latest round of tariffs spread around the world, the Hong Kong-based (and Cayman Islands-registered) conglomerate CK Hutchinson Holdings caught global markets off guard. Straight out of the blue, the company announced that it was selling 80% of its subsidiary Hutchinson Port Holdings, including its 90% stake in the Balboa and Cristobal docks at either end of the Panama Canal, to BlackRock, the world’s largest investment manager.

An Associated Press article reported that the sale effectively puts “the ports under American control after President Donald Trump [had] alleged Chinese interference with the operations of the critical shipping lane.” In a speech to the US Congress on March 4, Donald Trump bragged:

To further enhance our national security, my administration will be reclaiming the Panama Canal. And we’ve already started doing it.

Just today, a large American company announced they are buying both ports around the Panama Canal, and lots of other things having to do with the Panama Canal, and a couple of other canals.

CK Hutchison’s decision to sell up its port holdings company in a deal valued at nearly $23 billion, including $5 billion in debt, gives the BlackRock consortium control over dozens of ports in more than 20 countries. They include the Panamanian ports of Balboa and Cristobal, four ports in Mexico, 13 in Europe, 12 in the Middle East and Africa, and 11 in East Asia and the Pacific. Unsurprisingly, Hutchison will retain control of its 10 docks in China, including two in Hong Kong.

The move was driven by one main concern, reports the South China Morning Post — geopolitics:

CK Hutchison Holdings’ decision to sell its port operations in the Panama Canal and elsewhere is to mitigate against geopolitical risks even though it framed it as a purely commercial move, analysts and sources said, urging Hong Kong’s other major companies to also prepare for unparalleled global uncertainties.

There can be no denying it: the deal represents a geopolitical victory for the Trump administration as well as a setback for China’s belt-and-road ambitions, with some 6% of global trade passing through the Panama Canal. While this move will not fully wipe out China’s economic influence in Panama, it does represent a diplomatic recalibration and a shift towards closer alignment with Washington. It is also a major victory for Wall Street, as Benjamin Norton noted in his Geopolitical Economy Report:

BlackRock is the world’s biggest investment company. It managed a record high of $11.6 trillion in assets in the fourth quarter of 2024. (The top 500 investment managers on Earth together held $128 trillion in assets at the end of 2023.)

The Associated Press reported that the BlackRock-led consortium now controls at least 43 ports in 23 countries. The Wall Street giant’s subsidiary Global Infrastructure Partners was central to the US government-sponsored Partnership on Global Infrastructure and Investment (PGI), which was launched by the Joe Biden administration and the G7.

BlackRock’s billionaire CEO Larry Fink was invited to sit with Western heads of state at the G7 summit in Italy in 2024, where he called for “public-private partnerships” to help Wall Street firms buy up global infrastructure, especially in poor, formerly colonized countries.

BlackRock has enjoyed a very close relationship with the US government, under both Democrats and Republicans. Fink said before the US presidential election in November 2024 that it “really doesn’t matter” who wins, because both parties would benefit Wall Street.

Bloomberg reported that Fink personally called Trump and asked him to help BlackRock purchase the Panama Canal ports. The financial media outlet noted that the billionaire CEO bragged of BlackRock’s deep links with governments worldwide, stating, “We are increasingly the first call”.

Trying to Halt a 25-year Trend

As we have documented in numerous posts since the summer of 2021, the US’ apex strategic rival, China, has not only gained a foothold in the US’ backyard in the past three decades but has even begun to win the race for economic supremacy in the region. China is already South America’s largest trade partner, and as we saw with the recent opening of the Chinese-funded and controlled mega-port in Chancay, Peru, its Belt and Road Initiative promises to further cement that position.

Besides Hutchinson’s controlling stake of Panama’s two main ports since 2015, the Trump administration’s main bone of contention with the Central American nation was the fact that its government, like most governments in Latin America, had signed the Belt and Road Initiative. In fact, Panama was the first Latin America country to do so, in 2017. Since then, 20 other countries in the region have signed the initiative, including Venezuela, Chile, Uruguay, Ecuador, Bolivia, Costa Rica, Cuba, Perú, Nicaragua and Argentina.

To placate Washington’s demands, the Panamanian President José Raúl Mulino said he would not renew Panama’s Belt-and-Road membership when it comes up for review, becoming the first country in the region to leave Beijing’s global infrastructure initiative. He also mentioned the possibility of his government reconsidering the concession granted to Hutchinson Ports. The move sparked an unusually sharp rebuke from Beijing slamming Washington’s “Cold War mentality” in Latin America.

From Al Jazeera:

A spokesperson for the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the People’s Republic of China on Friday hit out at the United States for sabotaging the global infrastructure programme.

Beijing “firmly opposes the United States using pressure and coercion to smear and undermine Belt and Road cooperation,” said Lin Jian in a statement. “The US side’s attacks … once again expose its hegemonic nature.”

Referring to a visit this week to the region by Marco Rubio, Lin said the US Secretary of State’s comments “unjustly accuse China, deliberately sow discord between China and relevant Latin American countries, interfere in China’s internal affairs, and undermine China’s legitimate rights and interests”.

A Different Vision of Multipolarity

With Trump back in power, the US may have finally accepted the multipolar reality of today’s world but, as Conor noted in his recent post, The Empire Rebrands: Foreign Policy Under Trump 2.0, the Washington’s vision of multipolarity differs markedly from the one envisioned by China, Russia and other countries in the so-called “Global South”:

As many have pointed out, the US seeks win-lose transactions, and this is nothing new under Trump. As Glenn Diesen states:

In a multipolar world, security is enhanced by reducing the security competition between the great powers, while a mutually beneficial peace can exist under a balance of power and acceptance of the status quo. Even small- and medium-sized states can obtain more political autonomy from the great powers by cooperating with all great powers to diversify their economic connectivity. However, the US appears to be attempting to defeat China as its main rival, and coerce small and medium states into spheres of influence to ensure political and economic obedience.

This is now playing out in Latin America. It is no coincidence that the US’ new Secretary of State Marco Rubio’s first international tour was to the five Central American countries of Panama, El Salvador, Guatemala, the Dominican Republic and Costa Rica. Officially speaking, Rubio was visiting these countries for three main reasons: to stop mass illegal immigration to the US; to fight the “scourge of transnational criminal organizations and drug traffickers”; and “to counter China, and deepen economic partnerships to enhance prosperity in our hemisphere.”

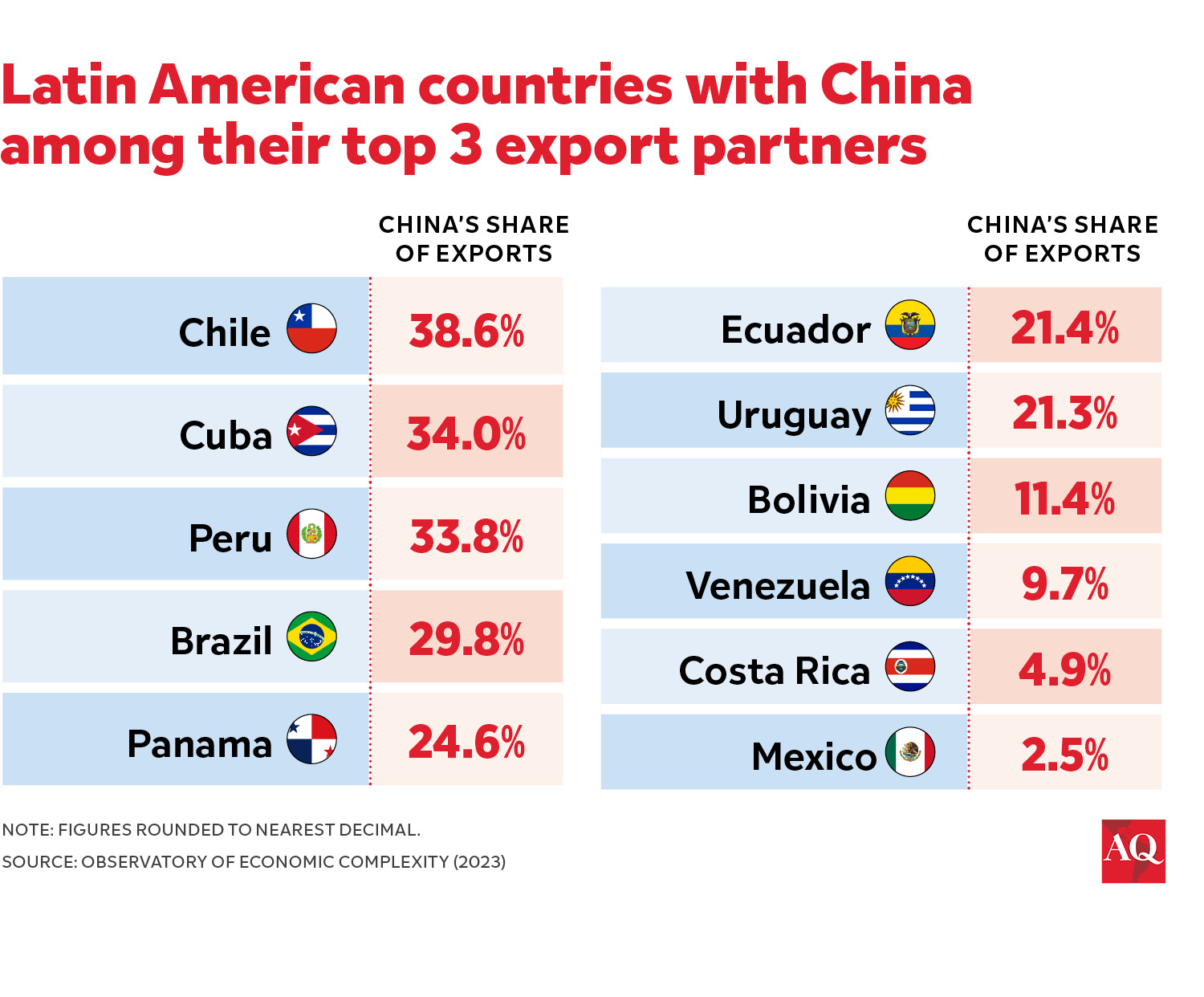

As a trading power, the US continues to holds significant sway over Central America. Pound for pound, it is still Latin America and the Caribbean’s largest trading partner. But that is predominantly due to its huge trade flows with Mexico, which account for a whopping 71% of all US-LatAm trade. As Reuters reported in 2022, if you take Mexico out of the equation, China has already overtaken the US as Latin America’s largest trading partner.

Meanwhile, China’s trade with Mexico, as with most parts of Central America, is growing fast, or at least was. And it is this trend that the Trump administration wants to halt, or even reverse. In order to achieve that, Trump 2.0 is, according to the Washington Post, “reviving” the two-centuries old Monroe Doctrine:

Long-attuned to U.S. slights both perceived and real, few [policy makers in the region] missed Trump’s throwaway line during his signing of executive orders just hours after his inauguration. Relations with Latin America “should be great,” he told reporters in the Oval Office. “They need us much more than we need them. We don’t need them.”

“What is the point of saying that?” asked the senior South American official, who spoke on the condition of anonymity to avoid drawing unwanted attention to his country. “It’s destroying trust. … Instead of inviting us to a new vision, he doesn’t invite anybody. There are only threats.”

Of course, the Monroe Doctrine never went away, it has just waxed and waned. During the first two decades of this century, it took a back seat as Washington focused on executing its War on Terror in the Middle East. As it squandered trillions of dollars spreading mayhem and death and breeding a whole new generation of terrorists, China began snapping up Latin American resources, in particular food, petroleum and strategic minerals like lithium.

But even during this time Washington was able to organise a failed coup d’état against Hugo Chavez’s government in Venezuela (2002) and a successful coup against Manuel Zelaya’s government in Honduras (2009). There was another unsuccessful coup against Venezuela’s Chavista government in 2019 as well as a successful one in Bolivia. The partly self-inflicted downfall of Peru’s socialist leader Pedro Castillo in 2022 also got the prior blessing from Washington’s ambassador in Lima and former CIA agent, Lisa Kenna .

By the early 2020s, it was clear that Washington had begun rejigging the Monroe Doctrine, a 202-year old US foreign policy position that opposed European colonialism on the American continent, in order to apply it to its most important strategic rivals of today, including China, Russia, Iran and even Hezbollah. Just this past week, a bipartisan bill titled the “No Hezbollah in Our Hemisphere Act” was introduced to the US Congress seeking to counter the Lebanese terrorist group’s influence in the region.

But it is China’s rapid rise in the US’ own “backyard” that is of greatest concern in Washington. Unlike the US, Beijing offers win-win trade and investment deals to national governments in the region. It also does not tend to meddle in internal politics, or at least hasn’t until now, preferring to let the money do the talking. As the former US Treasury Secretary Laurence Summers once admitted, “When a Latin American head of state asked me for something, I lectured them. While I was preaching, the Chinese were building airports.”

When it comes to international trade, win-win strategies tend to work far better than the zero sum games pursued by Washington. As China’s influence in the region has grown, it is the US military that has done a lot of the talking. In January 2023, General Laura Richardson, the then-Commander of US Southern Command (USSOUTHCOM), reminded the Atlantic Council of just how important Latin America’s resources are as well as the need to “box out” China and Russia from them.

[embedded content]

In other words, despite what the Washington Post may claim, the Trump Administration’s attempted shakedown of small and mid-sized Latin American countries does not represent the revival of the Monroe Doctrine. That said, it does represent a significant escalation in that trend, and one that many countries in the region and beyond will be keeping a close eye on — including, of course, China.

This time around, China’s government is taking a much harder line against Trump’s aggressive foreign and trade policy, including on the American continent. Last month, the country’s foreign minister Wang Yi warned that Latin America is not the “backyard” of any country amid attempts by the Trump administration to browbeat reengage with countries in the region.

“Latin America is the home of the Latin American people, not the backyard of any country,” Wang told Sosa, according to a statement released by Beijing. “China supports Latin American countries in defending their sovereignty, independence, and national dignity.”

If anything, China is seeking to intensify its strategic relations with countries in the region, particularly in South America. As the Mexican expert in international relations Brenda Estefan recently wrote last month for American Quarterly, the US may have notched up an early victory in Panama but convincing other countries, particularly in South America, to leave China’s orbit is likely to be more challenging:

Beijing currently maintains “strategic partnerships” with 10 of the 11 South American nations it engages with, with Guyana being the only exception, as it maintains only standard bilateral relations…

In January, during a visit to Beijing, I met with Chinese business leaders whose inclination to deepen their investments in Latin America, particularly in Mexico, was unmistakable. Our discussions revealed China no longer perceives Latin America as a resource supplier but as a pivotal part of its ambitious global economic agenda…

… Brazil—Latin America’s largest economy—is largely a lost cause for Washington, as it has significantly deepened its ties with Beijing. Chinese firms have invested in major infrastructure projects ranging from ports and railways to power grids. China is now Brazil’s largest trading partner, absorbing most of its exports, including soy, beef, coffee, and iron. In 2023, bilateral trade reached a record $181 billion. Moreover, Brazil and China have strengthened their geopolitical ties through BRICS, further complicating Washington’s ability to exert influence.

Of all the countries in the region, Peru draws the highest level of Chinese investment relative to GDP. The most significant of these investments was the recently inaugurated deep-water port at Chancay, which is intended to serve as a direct trade link between China and South America. After Trump’s electoral triumph, one of his advisors even proposed imposing tariffs on goods passing through Chancay.

Argentina is another interesting case. Before coming to power in late 2023, President Javier Milei talked openly about cutting all ties with China’s “murderous” dictatorship, only to backtrack once in office. There was a simple reason for this: since 2009 Argentina has had a currency swap arrangement with Beijing which has helped to ensure some degree of exchange rate stability for Argentina while also deepening trade between the two countries.

Given the sorry state of Argentina’s finances, Milei was in no position to turn his nose up at any outside financing. Indeed, by October 2024, almost exactly a year after telling Tucker Carlson that he would never trade with China due to its government’s left-wing, authoritarian proclivities, Javier Milei had nothing but fond words for the US’ main strategic rival today.

“China is a very interesting trading partner,” said Javier Milei, who just a year earlier had described the Chinese government as as “assassin.” They “do not make demands, the only thing they ask is that they not be bothered.”

Mexico, Between a Rock and a Hard Place

There can be no doubt that the US’s main priority is to drive a very large wedge between Mexico, its largest trade partner, and China, its second largest. According to Norwegian logistics firm Xeneta, the Mexico-China trade route is now the fastest-growing in the world, as China has sought to use Mexico’s fast-growing industrial base as a stepping stone for the US market. Given the extent of economic integration between the US and Mexico, Washington is determined to put an end to this trend.

And so far, Mexico has buckled each time the US has applied pressure. Last April, the AMLO government announced hundreds of “temporary” tariffs on imports from countries with whom it does not have a trade agreement. The tariffs were imposed on 544 imported products, including footwear, wood, plastic, electrical material, musical instruments, furniture, and steel, and ranged from 5% to 50% in size. They had one clear target in mind: imports from China though the word “China” was not mentioned once in the decree.

While the growing deployment of protectionist measures in Mexico, largely at the behest of the US, has elicited rare criticism in the Mexican business press, it seems that the Claudia Sheinbaum government is poised to continue this policy. From Bloomberg:

Mexican President Claudia Sheinbaum said her country would review tariffs on Chinese shipments, a move that could give the Trump administration a win in its push to build a “Fortress North America” that blocks shipments from the Asian nation.

“We have to review the tariffs that we have with China,” Sheinbaum said at a press conference Thursday.She pointed to Mexico’s problems in textile and shoe production, saying: “Much of the entry of Chinese products into Mexico caused this industry to fall in our country.”

The comments come after President Donald Trump offered major reprieves to Mexico and Canada, the US’s two largest trading partners, by exempting goods from those nations that are covered by the North American trade agreement known as USMCA from his 25% tariffs.

There’s a clear logic behind this. For a start, the economies of Mexico and the US are already so intertwined that trying to disentangle them will be an ungodly task. A staggering 83% of Mexico’s exports, many of which are goods assembled by US manufacturers in Mexican maquiladoras, go to the US. If a large part of those supply chains was threatened, the result for Mexico would be a deep economic crisis with millions losing their jobs, which in turn would endanger the ruling party MORENA’s entire economic project.

As I’ve noted in previous pieces, Mexico is caught in the middle of a titanic duel between the world’s two rival economic superpowers. While Brazil’s Lula may have invited Claudia Sheinbaum to the next BRICS meeting, the chances of Mexico becoming a BRICS nation any time soon is still razor thin, even as the Trump administration does everything it can to dynamite the USMCA trade deal, and its constituent economies.

For one thing, it will take years for Mexico to pivot its economy away from the US. Also, as AMLO said last year, Mexico’s geographic reality simply means it has little choice in the matter:

We cannot shut ourselves off, we cannot break up, we cannot isolate ourselves. It is a fact that we have 3,800 kilometres of shared border, for reasons of geopolitics (presumably in reference to the US’ invasion, occupation and appropriation of more than half of Mexico’s territory in the mid-19th century). With all due respect, we are not a European country, nor are we Brazil. We have this neighbourhood and, furthermore, if we agree on things, as we have done, we can help each other out…

However, helping out the US essentially means hitching Mexico’s economy to a declining superpower that appears to be on the verge of inflicting upon itself — and by extension, large parts of the world — a severe economic crisis while at the same time adopting an increasingly belligerent approach to adversaries and allies alike.

Also, this time around, China is adopting a much tougher response to US and broader Western provocations. Just a few days ago, Beijing imposed a 100% tariff on Canadian rapeseed oil, oilcake and peas and a 25% tariff on aquatic products and pork from Canada as a retaliation for Ottawa’s escalating tariffs on Chinese-made electric cars and other products.

While Mexico’s exports to China are negligible, representing just over 2% of the total, a chill on diplomatic relations with China will mean even greater dependence on the big neighbour to the North, which is just how Washington wants it.