Yves here. While this study’s findings on income-related exposure to pollution are interesting, there is still more than a bit of drunk looking under the headlight for his keys at work here. The authors used air pollution levels, where air pollution is more diffuse than toxins in water. Think the chemical alley in the lower Mississippi, the damaged aquifers and resultant benzene and other nasties in water near fracking sites, or Flint, Michigan, as a few of many examples. Admittedly, even in urban areas, pollution levels are generally the worst near major thoroughfares. But air quality is also often worst in major urban centers where rich people often live or at least work.

By Jonathan Colmer, Suvy Qin, John Voorheis, and Reed Walker. Originally published at VoxEU

Economic disparities have long been suspected to be a root cause of environmental inequality. But is this really the case? This column links data on income and wealth with data on air pollution exposure over 40 years to provide new evidence on the relationship between economic wellbeing and environmental quality in the US. The authors find that (1) the relationship between income, wealth, and pollution exposure is relatively weak, (2) non-Hispanic Black individuals face significantly higher pollution exposure than non-Hispanic white individuals at every income percentile of the distribution, and (3) large income windfalls lead to modest, though persistent, reductions in pollution exposure. The findings challenge the notion that reducing income inequality alone would significantly reduce environmental inequality.

While it is well established that disparities in environmental quality exist, it is less clear why these disparities exist. Understanding the relative importance of causes is critical if we hope to be effective in addressing environmental inequalities (Banzhaf et al. 2019). Social scientists have long posited that environmental inequality may be rooted in various forms of economic inequality. Hence, a reduction in economic inequality would provide the necessary income for individuals to access less polluted neighbourhoods, narrowing pollution exposure gaps. But is this true?

Previously, our understanding of the relationship between economic wellbeing and environmental exposures has been relatively cursory, largely due to data constraints. In our recent paper (Colmer et al. 2025), we combine 40 years of administrative microdata linking individual-level information on income and wealth for the near population of the US to high-resolution data on air pollution concentrations to provide systematic evidence on the relationship between pollution exposure and economic wellbeing. We document new descriptive facts about the relationship between income and ambient air pollution exposure, how these relationships differ by race and ethnicity, and how these income–pollution gradients have changed over time. We then identify a sample of individuals who experienced a one-time, plausibly exogenous windfall in income (most likely from lottery winnings) to examine the causal effect of changes in income on air pollution exposures.

We highlight three main findings:

- The relationship between income, wealth, and pollution is relatively weak.

- Black individuals are exposed to significantly higher levels of air pollution than white individuals at every single income percentile.

- Large increases in income lead to persistent but small reductions in air pollution exposure.

These findings challenge the idea that reductions in income inequality itself will significantly reduce environmental inequality.

New Evidence on the Income–Pollution Relationship

Historically, the correlation between income and air pollution exposure has been approximately zero. We found that in 1984, individuals at the top of the income distribution were, on average, exposed to similar pollution concentrations as those at the median or bottom of the income distribution. While air quality has improved substantially in the intervening decades, with pollution concentrations declining by more than 60% and the income–pollution gradient becoming more negatively sloped, the relationship between income and air pollution remains relatively flat.

Race-Specific Differences

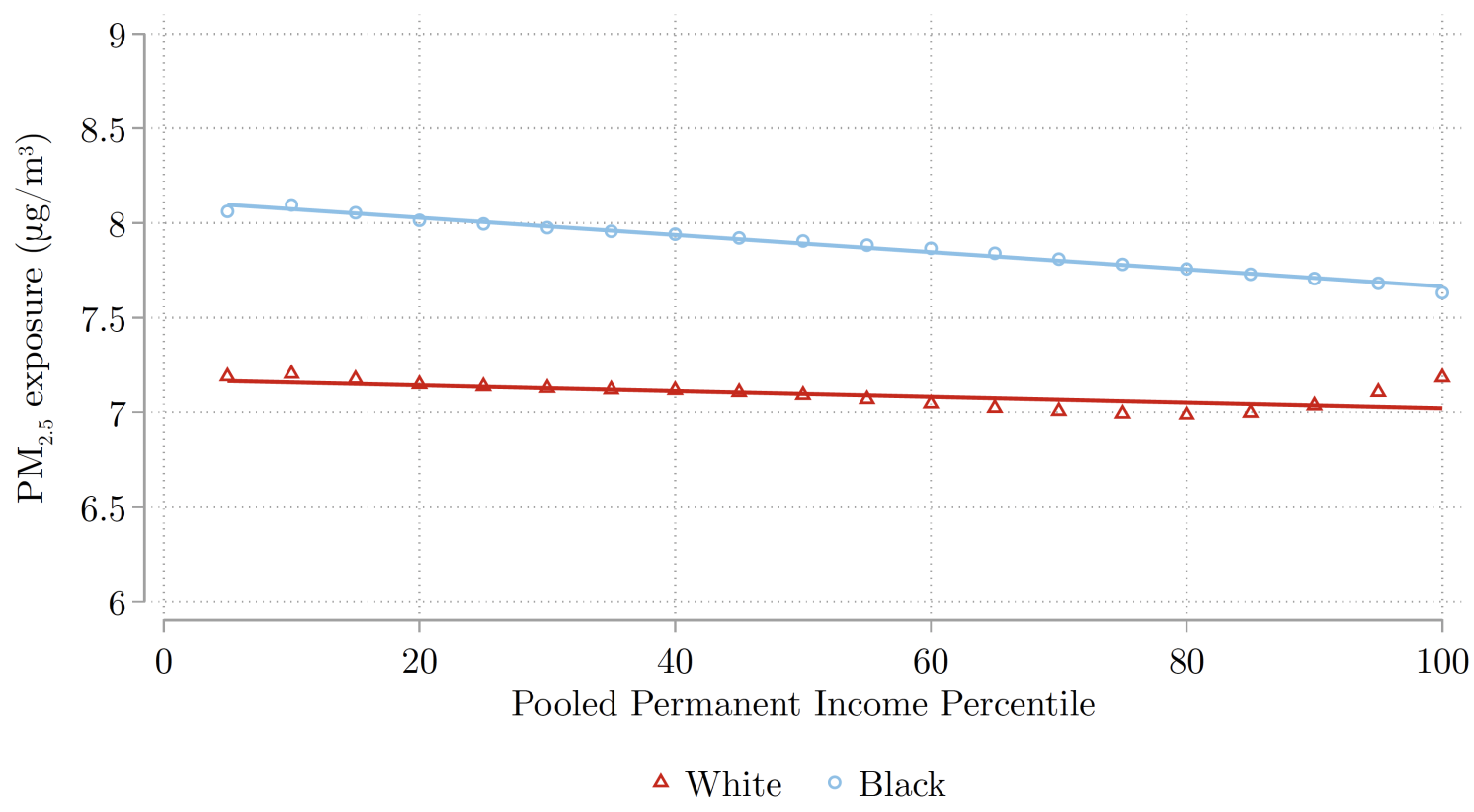

It is possible, however, that the income–pollution relationship might differ across demographic groups. To explore this possibility, we estimate income–pollution relationships separately by race. Similar to our overall estimates, we find that the income–pollution relationships are relatively flat and similar across demographic groups. However, Black individuals are exposed to higher pollution concentrations than white individuals at every single percentile of the national income distribution. This means that the richest Black individuals are, on average, exposed to worse air quality than the poorest white individuals. Again, this pattern has persisted over time, despite overall improvements in US air quality. We also show that these findings hold in every single location type (central cities, rural areas, suburban areas) and even within metro areas. Across different measures of pollution, different measures of income or wealth, different places, and different time periods, a simple fact endures: racial minorities are, on average, exposed to higher levels of air pollution at every single income percentile.

Figure 1 The relationship between permanent income and PM2.5 exposure, by race

a) 1984

b) 2016

Note: These figures plot the average PM2.5 concentration by permanent income percentile for a given year, separately by race. The income percentiles are constructed from all prime-aged US tax filers in a given year who report positive adjusted gross income. The plotted line represents the best linear fit to these conditional means.

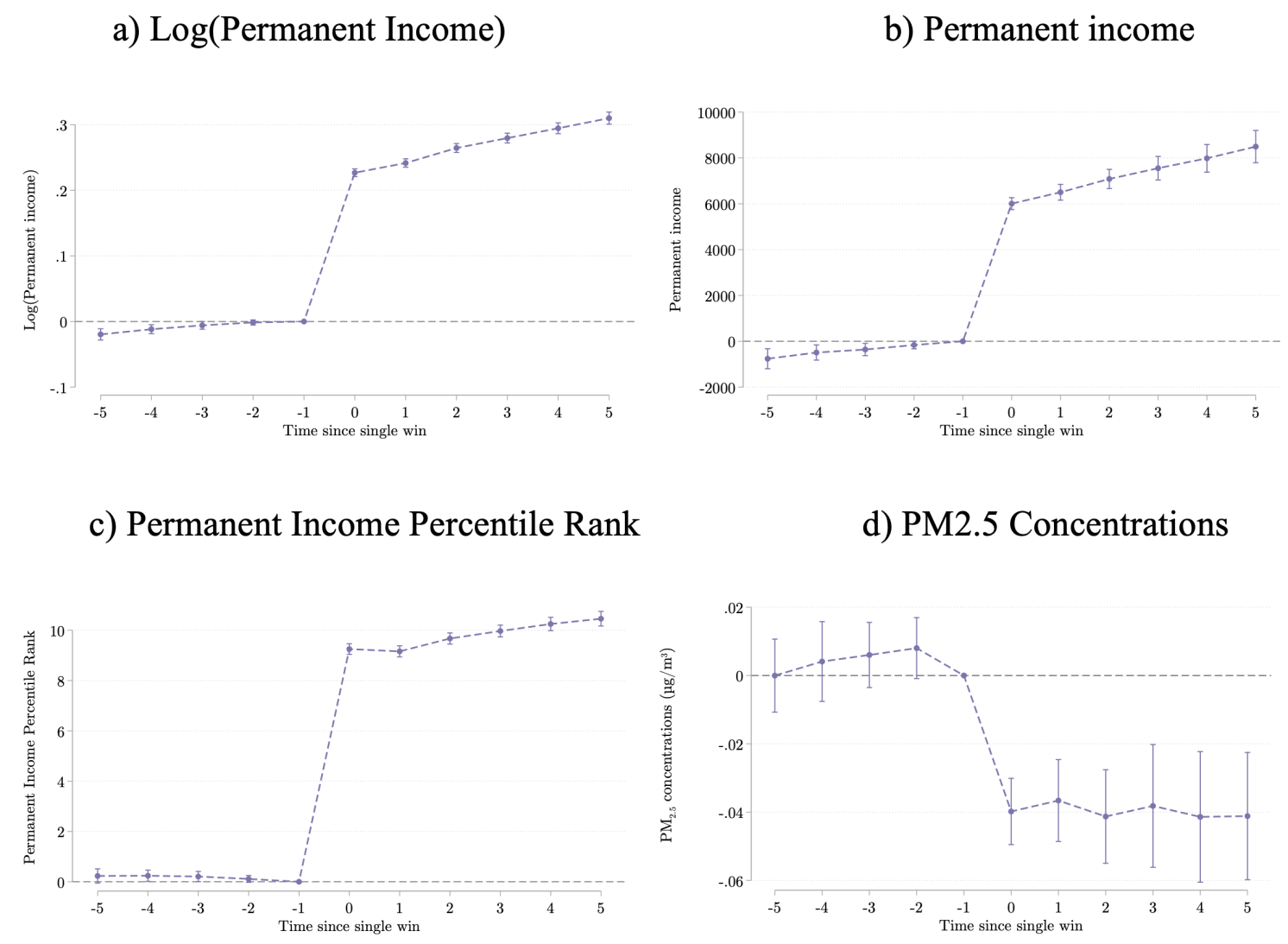

What Happens When People Get More Money?

While these facts tell us about equilibrium outcomes, they do not tell us the extent to which relative improvements in income or wealth may lead to relative improvements in air quality. To better understand the causal effect of income or wealth on air pollution exposure, we leverage a set of individuals in our data who experienced a large one-time income gain. We find that an average windfall of $90,000 is associated with a persistent 0.04 ug/m3 reduction in PM2.5 concentration – a small effect.

Figure 2 The effects of income windfall events

What Does This Imply for Environmental Inequality?

Our findings suggest a fundamental limitation of income-based approaches in addressing environmental inequality: reducing income inequality alone will not eliminate disparities in pollution exposure. Using our empirical estimates, simple back-of-the-envelope calculations suggest that harmonising median income between Black and white individuals would be associated with a 10% reduction in the overall Black–white PM2.5 gap in 2016. We note, however, that our conclusions do not reflect various ways in which aggregate changes to the income or wealth of a community or group may affect environmental exposures, not simply through mobility, but through channels such as political engagement and/or collective action (Banzhaf 2012, Banzhaf et al. 2019). Understanding how these broader social processes influence relative environmental exposures remains an interesting and important area for future research.

Rethinking the Link Between Economic and environmental Inequality

While income inequality and environmental inequality are connected, the link appears less robust than researchers have historically theorised. We find that the relationship between an individuals’ income and air pollution exposure was approximately zero in 1984 and has become more negative since then, but it remains quite flat. At every single income percentile, Black individuals are exposed to higher levels of pollution than white individuals. While individuals with higher incomes tend to live in cleaner neighbourhoods within metro areas, racial gaps in pollution exposure persist. Even large increases in income appear to have little effect on an individuals’ pollution exposure. The fundamental driver of environmental inequality is not solely rooted in income inequality, but requires further inquiry.

Authors’ note: Any opinions and conclusions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not represent the views of the U.S. Census Bureau.

See original post for references