The U.S. intelligence community published its 2025 annual threat assessment on March 25. For the first time in more than a decade climate change didn’t make the cut. That’s not entirely surprising considering the Trump Administration’s ideological leanings, yet one could argue it is being prioritized in other ways — and rather than mitigation, it is acceleration that is the focus.

Geopolitics have almost always trumped any concern over climate change, but the economic war against China drives that point home with an exclamation point. That’s because Beijing went all in on clean energy technology in recent years — to the point China now has the capacity to lead a global energy transformation — only for the US, EU, and others to essentially say they don’t want it.

They are instead turning to a combination of de-risking and going dirty in what amounts to coordinated rug pull from underneath Beijing’s strategy to lead the world in clean energy technology.

The Washington-instigated trade war might end up harming the US the most (if Trump stays the course, which is never certain), will inflict damage on China too, and it will also inflict major damage on the effort to at least slow global CO2 emissions.

In a way it is reminiscent of what’s long been US strategy: when in doubt, set things ablaze and sit back in the safety of the North American island and watch people tear each other apart.

This time, however, Washington is weaponizing the global economy and climate. The effects will be global and, in the case of climate damage, long-lasting. Essentially the US is embracing climate change as the ultimate destabilizer — as long as it means weakening China.

I’ll look here at China’s clean tech strategy and how the economic war calls it into question. A Wednesday post will focus more on clean energy effects in the “Global South” and the “West.”

China’s “Overcapacity”

According to CarbonBrief, in 2023, 39 percent of all Chinese investment was in clean-energy manufacturing, and a gargantuan 40 percent of China’s GDP growth came from clean-energy sectors. That means the industry is now front and center to China’s wider economic and industrial development strategy.

Beijing enacted a wave of initiatives in recent years to drive local deployment of clean tech while simultaneously restricting foreign competition in the Chinese market. Like other industries, Chinese clean-energy manufacturers quickly became national players and then global players.

Now, all this clean tech comes with all the usual caveats about it not being a fix to what’s coming. It is, after all, a capitalist economic competitiveness strategy, which includes other items like building energy intensive, environmentally destructive data centers and leading the world in attempts to drive human labor extinct through automation. Even in China with all this capacity it’s not all good news as far as emissions are concerned. According to the Transnational Institute:

This does not mean, however, that clean energy has displaced fossil fuels in China’s energy mix. While fossil fuels now make up less than half of the country’s installed generation capacity, compared to two-thirds a decade ago, in absolute terms the use of fossil fuels – coal, most importantly – has continued to rise, albeit at a slower rate. China’s energy shift is defined more by expansion than transition.

But it’s hard to conclude that China’s investments aren’t better than nothing:

China’s investments in clean tech have dramatically lowered costs around the world, including across the Global South.

If China hadn’t made these investments, how much aid would the Global South have needed to achieve similar levels of clean energy growth?

Chart source:

The… pic.twitter.com/FFVvGlIUcq— Kyle Chan (@kyleichan) November 14, 2024

Western leaders say that China is behaving poorly by subsidizing its clean tech industry and is undercutting Western competitors. It’s an argument overflowing with hypocrisy. Again from the Transnational Institute:

First, western elites had no problem with cheap Chinese imports when the products were low-down the value chain, and thus no threat to their corporations, which in any case have directly benefited from cheap Chinese labour for decades. Only now that high-value Chinese technology threatens to dominate western competitors is their concern about ‘dumping’. Second, all governments accept that climate change requires at least some degree of state intervention to hasten the advance of zero-carbon technologies. Given the urgency of climate action, concerns about ‘overcapacity’ should be seen as a red-herring. Finally, as we will discuss further below, the EU and especially the US have also rolled-out subsidies for the development of their own green tech firms, just like China, and have sought to protect their market leaders in many industry sectors, in the US case most famously in semiconductors. In reality, the tariffs on Chinese green tech have little to do with fairness and a lot to do with geopolitical competition: western politicians and CEOs know that their companies cannot compete with cheaper and higher-quality Chinese clean-energy goods.

Even Larry Summers apparently gets it:

I’m normally not a big fan, but this is an absolutely brilliant answer by Larry Summers to the oft-repeated argument that China is somehow “cheating” in trade.

In fact it’s probably the best answer I’ve ever heard on this.

It goes back to the point I was making… pic.twitter.com/bnqRykzTGK

— Arnaud Bertrand (@RnaudBertrand) April 10, 2025

Meanwhile, Team Trump opts for fossil fuels and tariffs while the previous American administration went with tariffs on Chinese clean tech and the fantasy that the US could lead a global green transition.

Last August, Brian Deese – Director of the White House National Economic Council from 2021 to 2023 – called last year for a Clean Energy Marshall Plan in the pages of Foreign Affairs. Despite China’s enormous lead and tangible progress, Deese (and other Biden officals) were pushing the line that the US should be the one playing China’s role if anyone plays it. It was astonishing hubris, even by US standards. From Adam Tooze:

[Deese’s] truly bamboozling proposition is that what the world really needs is American clean energy technology! The obvious question is simply, what American clean energy technology?

…As Deese gamely observers: “The good news is that most of the technologies necessary, from solar power to battery storage to wind turbines, are already commercially scalable.” Yup! this is true. But the problem from Washington’s point of view is that it is not the US that is leading that commercialization. But China. On a huge scale. Against US resistance.

What are the technologies that Deese sees his Clean Energy Marshall Plan promoting? They are a strange list: geothermal, hydrogen, carbon capture, nuclear. At this point the verbal slight of hand becomes evident. What Deese is promoting is indeed a “Clean Energy” Marshall Plan, not a Green energy Plan.

Though some of Deese’s preferred technologies may matter in the long-term, none of them is widely expected to play an important part in the energy transition in the near term. And the fact that the US is a serious player in hydrogen, geothermal and carbon capture is not by accident. What they all have in common is that they are the favored “clean technologies” of US fossil fuel industries and widely regarded with suspicion with those interested in a comprehensive green energy shift.

The minor differences between the Biden and Trump plans highlight much. As usual the Democrat’s plan is a dressed up horrid roadmap but while the Trump version rips away the niceties. Boiled down, they are both visions for a future that include a climate ravaged planet with America still reigning supreme. And so here we are with Trump doubling down on “drill, baby, drill” and building upon Biden’s tariffs on the Chinese clean tech industry.

The hope — as 350.org points out — is that the US manages only to hurt itself and not derail global minimal efforts at emissions reduction. From The Guardian:

Analysis by the climate campaign group 350.org has found that despite rising costs and falling green investment in the US, Trump’s trade war will not affect the energy transition and renewables trade globally.

It said the US was already “merely a footnote, not a global player” in the race to end the use of fossil fuels. Only 4% of China’s clean tech exports go to the US, it said, in a trade sector where sales volume grew by about 30% last year.

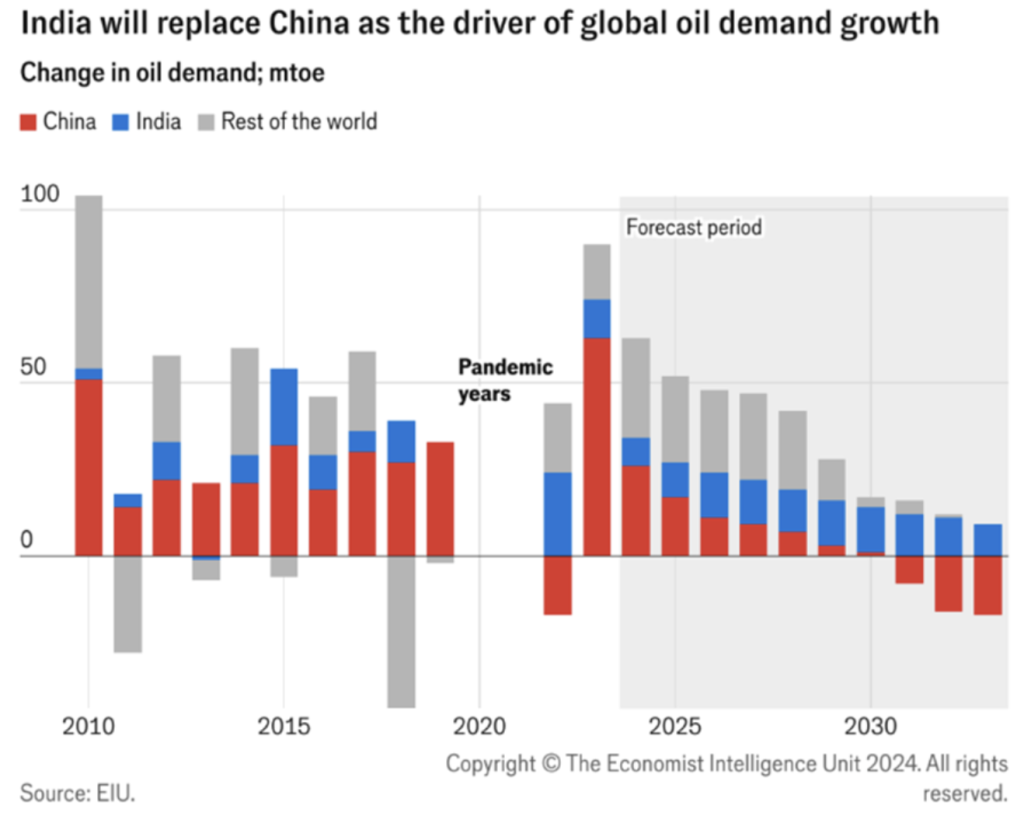

But that also assumes the US stops with tariffs and other parts of the world don’t go — or aren’t dragged — along. The EU is already mid-stream on its “de-risk” from China, but is pausing to reassess. (While it has always made sense for the EU to build out Eurasian ties, don’t hold your breath.) And the “Global South” faces its own inflection point, as well as a debt crisis. The trade war also comes at a time when China is relinquishing its position as the largest driver of global oil demand — and at a faster pace than previously expected in part due to Beijing’s focus on high and clean tech as growth drivers.

Gulf countries are now shifting their focus to the Indian market, which is expected to become the largest driver of global oil demand by 2033.

Geopolitically, one can make of that what they want, but other pressures on the global oil market are likely to have repercussions on the economies of the Gulf states, leading to obvious choices in the oil states’ budgets. According to Emirates Policy Center, the first items on the chopping block will be “economic and social development projects…including green energy initiatives.”

So let’s say the “West” is willing to endure circles of hell pain, which will likely shatter their economies and societies, in a drawn out “de-risk” from China. Or they just attempt to limit their economic war to clean tech industry. They still represent almost 30% of global trade in goods and services and 43% of global GDP. Throw Japan, South Korea, and others like India, which might stay partially on board, and Beijing could have issues with simply redirecting its economic strategy, according to Xue Gong writes at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace:

…while China seeks to leverage the Global South to counter tensions with the Global North, it still relies on high-quality foreign direct investments (FDI) from the West to support its economic transition. Despite expanding trade and investments with the Global South, China’s dependence on Western markets remains strong.

And here’s Reuters:

China has no great options, though. It will court other markets in Asia, Europe and the rest of the world, but this may not be much of an escape valve. Other countries have much smaller markets than the U.S., and local economies are also taking a hit from the tariffs. Many are also wary of allowing more cheap Chinese products in.

Domestically, a currency devaluation would be the simplest way to cushion the tariffs’ impact but that could trigger capital outflows, while also alienating trade partners China may try to court. China has so far allowed very limited yuan depreciation.

More subsidies, export tax rebates or other forms of stimulus could be on the cards, but this also risks exacerbating industrial overcapacity and fuelling more deflationary pressures. Analysts have advocated for years for policies that would boost domestic demand.

But despite Beijing’s declarations, little has been done to meaningfully increase household consumption, given that the bold policy shifts that would be required could prove disruptive to the manufacturing sector in the short term.

Hitting back with its own tariffs and export controls may not be very effective, given China ships to the U.S. about three times as much in goods than around $160 billion it imports. But it may be the only option if Beijing believes it has a higher pain threshold than Washington has.

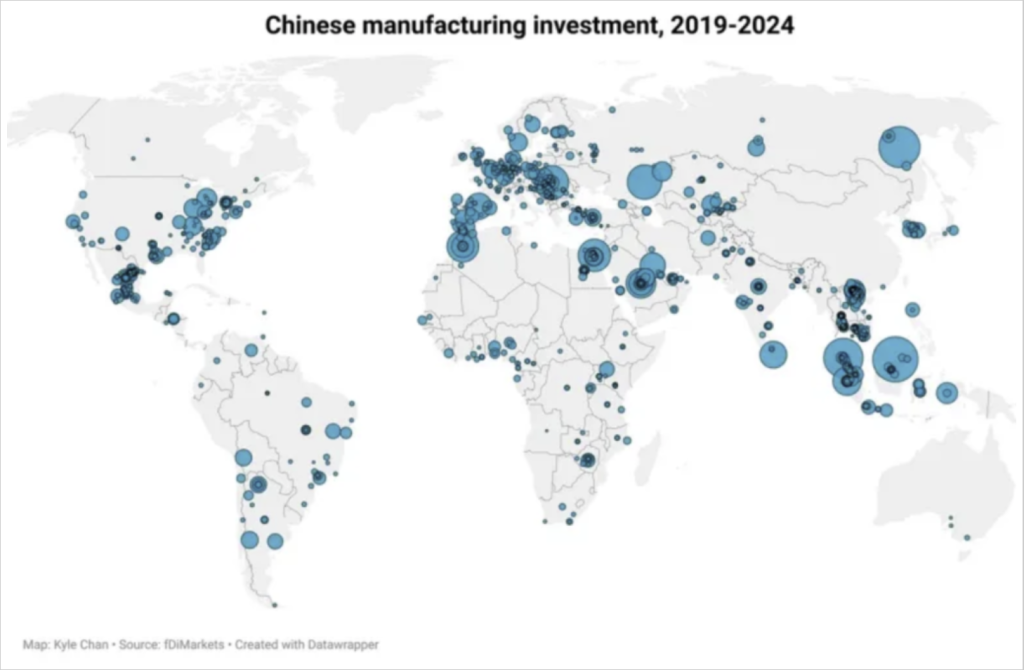

China’s big bet to combat efforts to isolate it was to invest everywhere. Kyle Chan has a lot at High Capacity on the incredible amount of work China has done to secure access to markets:

Chinese companies are racing to build factories around the world and forge new global supply chains, driven by a desire to circumvent tariffs and secure access to markets. Chinese companies have been building manufacturing plants directly in large target markets, such as the EU and Brazil. And they’ve been building plants in “connector countries” like Mexico and Vietnam that provide access to developed markets through trade agreements. Morocco, for example, has emerged as a surprisingly popular destination for Chinese investment tied to EV and battery manufacturing due to its trade agreements with both the US and the EU.

Just take a look at the map:

How do you derisk/decouple/whatever from that?

One argument in Foreign Affairs is that the US needs a “new strategy of allied scale to offset Beijing’s enduring advantages.” Here’s what that entails:

During the Cold War, the United States and its allies outclassed the Soviet Union. Today, a slightly expanded configuration would handily outclass China. Together, Australia, Canada, India, Japan, Korea, Mexico, New Zealand, the United States, and the European Union have a combined economy of $60 trillion to China’s $18 trillion, an amount more than three times as large as China’s at market exchange rates and still more than twice as large adjusting for purchasing power. It would account for roughly half of all global manufacturing (to China’s roughly one-third) and for far more active patents and top-cited journal articles than China does. It would account for $1.5 trillion in annual defense spending, roughly twice China’s. And it would displace China as the top trading partner of almost all states. (China is today the top trading partner of 120 states.)

Essentially another isolation effort similar to the failed one against Russia but with a lot more heavy lifting and the hope that everything goes right and/or Beijing doesn’t retaliate too much. Even if the US and EU are successful in damaging China’s clean tech industry, it’s hard to see derisking from China’s overwhelming advantage in necessity items without burning everything down with the belief you can reemerge on top. If you give the US administration any benefit of the doubt and conclude they aren’t complete morons, the charitable view is that they’re callous, reckless and willing to force a game of Russian Roulette with a fully loaded gun.