Yves here. European NATO members, with few exceptions, have worked themselves into a frenzy over the belated recognition that Russia is winning the Ukraine war and the US is about to leave them to their own devices, defense-wise. That of course means the evil Putin will soon be in Paris! Hence militarism is now in vogue, even though, with UK and European economies already in a sorry state due to sanctions-induced energy cost increase, they are under budget stress. Big arms programs will only make that worse.

So “military Keynesianism” is the way to square that circle, at least in theory . But how well will that work in practice?

By George Georgiou, an economist who for many years worked at the Central Bank of Cyprus in various senior roles, including Head of Governor’s Office during the financial crisis

By spending more on defence, we will deliver the stability that underpins economic growth, and will unlock prosperity through new jobs, skills and opportunity across the country

– Keir Starmer, press release, 25 February 2025

Introduction

Europe’s commitment to rearm as a response to the perceived threat from Russia, has been partly justified on the grounds that an increase in military spending will stimulate economic growth. In other words, military expenditure is seen by policymakers as a form of Keynesian pump priming. This is a neat argument used by European policymakers desperate to persuade their electorates to accept large increases in defence spending at the expense of the welfare state. However, there is very little evidence that Keynesian militarism will actually provide the intended result. Indeed, the economic reality of military production and procurement undermines the implicit assumption that the defence spending multiplier is sufficiently large to generate a Keynesian type stimulus.

Military Production and Procurement

A significant proportion of military equipment in some European countries is sourced from overseas rather than domestically produced. Weapons systems are imported from America, Israel, South Korea, and elsewhere. Table 1 below has been adapted from a table in the 2024 edition of Trends in International Arms Transfers published by the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute in March 2025. The most striking observation is the dominance of arms supplies from America. The share of imports from America varies from 45% (Poland) to 97% (Netherlands). As SIPRI states:

“Arms imports by the European NATO members more than doubled between 2015–19 and 2020–24 (+105 per cent). The USA supplied 64 per cent of these arms, a substantially larger share than in 2015–19 (52 per cent)”.

Table 1- Selected European NATO importers of major arms and their main suppliers, 2020-24

Source: Table has been adapted from Table 2 in SIPRI’s Trends in International Arms Transfers, 2024

Due to capacity constraints in the European arms industry and the dominance of American technical know-how, it is unlikely in the short to medium term that Europe will be able to replace American weaponry with domestically produced armaments. Hence, an increase in European military outlays will benefit the US economy significantly more than Europe.

Even in those countries, like France for example, where weapons systems are sourced primarily from domestic producers, many of the components are often imported. Thus, the impact of military spending on the domestic economy is limited.

Another factor that needs to be considered is the production process. The increasing sophistication of weapons systems involves capital intensive production methods rather than the labour-intensive methods that were common prior to the 1980s. The ever-increasing sophistication of fighter jets, tanks and war ships often results in long lead times and cost overruns. The post-WWII history of weapons systems is also replete with examples of armaments that are unreliable or unsuitable. This is particularly the case with tanks, fighter jets and ships, but similar problems have occurred with relatively simple products. For example, the UK government is currently having to replace 120.000 body armour plates due to cracks.

Technological Spin-Off

Advocates of Keynesian militarism argue that one of the ways in which military expenditure stimulates economic growth, is through technical innovation in the military sector which eventually spins-off into the civilian sector. The empirical evidence for technological spin-off is inconclusive. Some academic studies have found that during the cold war, when there was an arms race and military outlays were higher than the post-cold war period, there was some evidence of a technological spin-off. Other studies have found little or no evidence of spin-off. Indeed, the spin-off tends to be in the opposite direction, from the civilian to the military sector, sometimes referred to as ‘spin-in’. A 2005 research paper by Paul Dunne and Duncan Watson using panel data, concludes as follows:

One of the problems of measuring the impact of spin-off is the long-time lag between the onset of military R&D and actual applications in the civilian sector. These time lags can stretch over several years thus overlapping both the economic dynamics of the civilian economy and the interplay between spin-off and spin-in. It thus becomes difficult to disentangle cause and effect.

The Real Beneficiaries of Rearmament

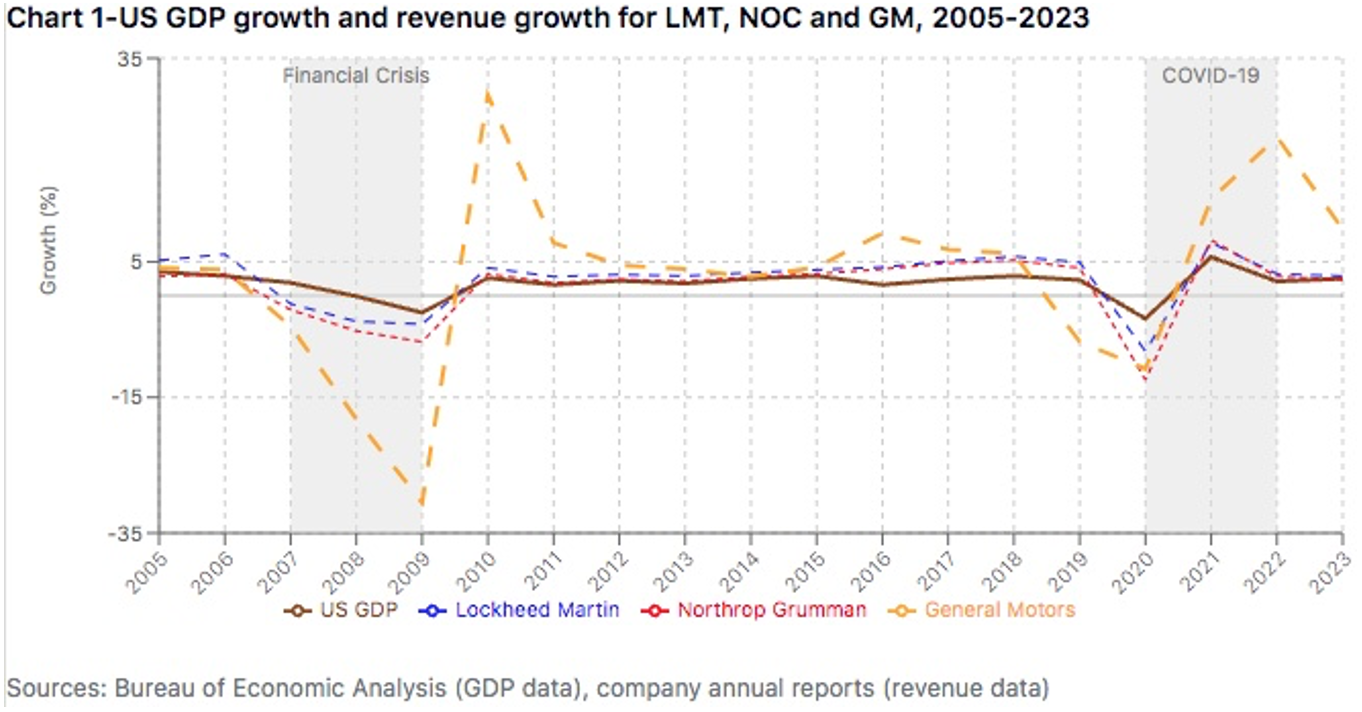

While politicians across Europe try to fool themselves and their electorates that increased military spending is a form of Keynesian stimulus, the real stimulus will be in the profits and stock price of the large arms manufacturers as well as the bank accounts of corrupt state officials. In an article published in Naked Capitalism on 31 January of this year, I argued that arms producers are the main beneficiaries of conflict. Although there is nothing new in this argument, it was useful to provide some numbers. Chart 1 below is taken from the January article and illustrates the stable performance of two large American arms manufacturers in relation to the instability of a non-arms manufacturer.

As regards corrupt state officials, the history of arms contracts embroiled in corruption is long. The interested reader can find them on the Internet. For the purposes of our discussion, a pertinent example is the case of Ursula von der Leyen’s handling of military related contracts when she was Germany’s minister of defence between 2013 and 2019. Allegations of impropriety and implicit corruption surrounding these contracts, still linger. This is the same von der Leyen who in March of this year proposed setting up a European Sales Mechanism that would allow the pooling of military procurement using an EU defence funds. Von der Leyen’s murky past as German defence minister, together with her controversial handling of the Covid vaccine contracts, should serve as a warning.

Conclusion

The economic narrative used by politicians in European NATO countries to justify increases in military spending, needs to be viewed with a dose of skepticism. Ultimately, any decision to increase military expenditure needs to be based on military and strategic considerations rather than perceived economic benefits which may or, more likely, may not materialise. Nor should the supposed economic benefits be used to deflect from the discredited austerity agenda that seems to be now firmly back on the table. Keynesian militarism is a poor substitute for Keynesianism.