Yves here. Even though this post stresses the opportunity for BRICS members to play a heftier role in international lending and development programs, it effectively admits BRICS is pretty much nowwhere on this front. The Kazan Declaration of October 2024 did not commit BRICS to developing new institutions. It instead explicitly reaffirmed the IMF as the sovereign bailouter-in-chief. The article explains, “It has not developed sustainable long-term institutions that could challenge the existing system.” It also describes conflicts among the biggest players that impede developing new funding mechanisms.

The author points to other BRICS initiatives, such as strengthening regional trade ties, but that is not the same as having a BRICS institutions in addition to the (admitted to be not very effective) New Development Bank. Instead, the author recommends that small and middle sized states lobby for greater influence in existing financial institutions.

That is not likely to get very far. As Africa Watch explains:

Yesterday [April 23], US Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent delivered an interesting speech in Washington at the Institute of International Finance…

The speech was highly anticipated because there has been chatter about the future of the two Bretton Woods Institutions in the wake of the Trump Shock. That shock has already delivered the unexpected shutdown of U.S.A.I.D and the withdrawal of the US from the World Health Organization (WHO). Many have wondered whether a withdrawal from the IMF and World Bank was also on the cards.

The uncertainty was largely settled with yesterday’s address where Bessent was unequivocal in stating: “Far from stepping back, America […] seeks to expand U.S. leadership in international institutions like the IMF and World Bank.” In other words, the US ain’t going nowhere!

Bessent’s renewed commitment to the IMF (“the Fund”) and World Bank (“the Bank”) does not come as a surprise to me. In the last couple of weeks, I have heard pontifications from eminent social scientists (mostly from the global North) predicting a US withdrawal with certainty. These analyses have struck me as naive.

In my estimation, there are very few, if at all any, multilateral institutions that have delivered a “return on investment” for the US like the Fund and the Bank. This is why Bessent yesterday reaffirmed his country’s commitment to the two institutions.

Unlike other multilateral organizations, the US, on its own, has effective veto power when it comes to the most consequential decisions of the World Bank and the IMF. No other country has this power. And in no other multilateral setting does the US have this singular power. Not even in the UN’s Security Council where the US has to contend with the veto powers of the other four permanent members

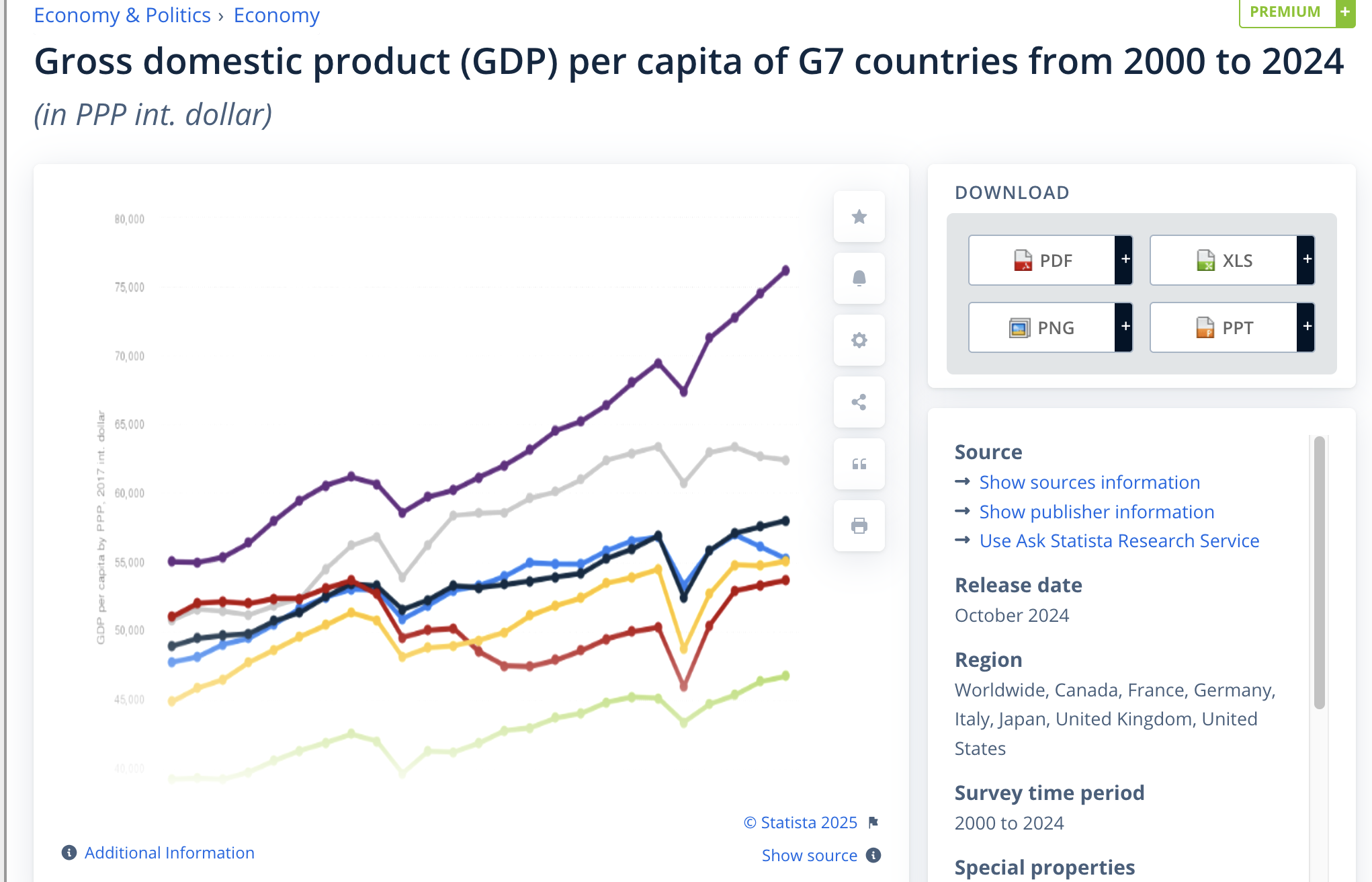

The underlying issue, which is seldom acknowledged, is the despite their greater GDP and population heft, BRICS nations are much poorer. The poor do not good bankers make. You need a financial surplus to be able to make loans. Although neither chart is on target (BRICS is now bigger, its chart includes forecasts through 2029), the disparity in GDP per capita is os great as to make the point:

By Heena Makhija, an independent foreign policy analyst who specializes in the study of International Organizations, Multilateralism, India at the UN, and Global Norms. Originally published by Observer Research Foundation; cross posted from InfoBRICS

Donald Trump’s return to office saw the United States (US) withdrawing from its multilateral commitments and announcing plans to increase tariffs on exports, fueling the possibility of a trade war. Even in a multipolar world, the US remains the largest shareholder in multilateral financial institutions such as the World Bank and a shift in policy will have implications for institutions as well as markets. The fragility of the existing global financial system also revives the opportunity for non-Western-led entities such as BRICS to strengthen their position as a counterbalancing actor.

Addressing Altered Global Dynamics: BRICS to BRICS Plus

The Bretton Wood institutions, a product of the West, often adopted a callous approach towards the needs of the developing world. A study of 81 developing countries between 1986 to 2016 showcases the negligible impact of the International Monetary Fund (IMF)’s structural ‘conditional’ loans on the recipient states. The gap paved the way for ‘minilateral’ financial groupings such as G77, where developing countries collaborated at the global level. The formation of ‘BRICS’ emerged from the rapid rise of economies such as Brazil, Russia, China, India, and South Africa, and their significance in global financial governance.

The gap paved the way for ‘minilateral’ financial groupings such as G77, where developing countries collaborated at the global level.

Since its inception, BRICS has adapted to the evolving global economic realities to counter the post-war narrative. In the aftermath of the 2008 Financial Crisis, at its first summit, BRICS member countries committed to advancing the “reform of international financial institutions, so as to reflect changes in the global economy”. In 2023, acknowledging the need for expansion, BRICS further invited six emerging economies—Argentina, Egypt, Ethiopia, Iran, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates—to join the bloc at the 15th BRICS Summit.

Challenge of Pivoting

At the 2024 Summit, Prime Minister Modi highlighted the significance of economic cooperation and expansion—the ‘BRICS’ economy now stood at the value of more US$ 30 trillion dollars. The membership expansion is relevant, but the institution has been facing severe criticism for failing to address the financial concerns of the Global South and merely being a symbolic association—more statements, less substance.

Firstly, BRICS institutionalised itself through the Annual Leaders’ Summit and ambitious initiatives such as the New Development Bank (NDB) and the BRICS Contingent Reserve Arrangement (CRA). However, due to its tepid growth over the years, BRICS gives an impression of being a short-term, single-issue response to the financial crisis. It has not developed sustainable long-term institutions that could challenge the existing system. For instance, NDB’s focus on the needs of emerging economies through quick loans, competitive lending rates, and use of local currency was touted as its differentiating factor from the Western-dominated institutions. Yet, NDB’s local currency lending remains low. NDB’s regulatory “country system approach” towards infrastructure projects has also been condemned for leaving the task of monitoring to local agencies.

The five founding members have equal voting shares, and even with its expansion, they are designated to hold no less than 55 percent of the voting rights.

Secondly, geopolitical developments involving the primary shareholders—Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and the turbulent India–China bilateral relations—tend to cast a shadow on consensus-based financial groupings as national interest takes precedence. The five founding members have equal voting shares, and even with its expansion, they are designated to hold no less than 55 percent of the voting rights. BRICS’ influence and its potential to bring about global institutional reforms have been hindered by a lack of consensus among its ‘politically polarised’ members and rising geopolitical tensions. The 2024 Fitch Ratings also highlight a concerning tilt towards China, citing the construction of NDB’s headquarters in Shanghai and the push to replace the dollar with yuan— both of which have raised concerns among other member countries. Given these contradictions, BRICS must pivot and consolidate itself as a ‘balanced’ alternative to the existing multilateral financial institutions.

Towards a Multilateral Financial Institution: Scope for BRICS

As its geopolitical balancing act, other members like India cultivated closer economic ties with the US. Trump and Modi’s recent meeting led to the “US–India COMPACT (Catalyzing Opportunities for Military Partnership, Accelerated Commerce & Technology) which included a bold new goal for bilateral trade—“Mission 500”, aiming to double total bilateral trade to US$500 billion by 2030 alongside fostering partnerships such as the QUAD. Yet, on the institutional multilateral front, BRICS still exists as a comprehensive multilateral platform for promoting the financial interests of developing countries through greater South-South cooperation—it would be shortsighted to underestimate the economic influence of a non-Western-led initiative.

Several key arguments support the potential of BRICS, from its market share to its institutional capabilities. First, the member countries have a fair shot at enhancing economic cooperation through strong intra-regional trade given the geographical proximity. BRICS’ exports witnessed an increase from US$ 493.9 billion in 2001 to US$ 4651.6 billion in 2021. The 10 member nations account for almost 40 percent of crude oil—production and exports; and one-quarter of the global GDP. Second, at the last summit in Kazan, 34 countries officially applied for membership including resource-rich and fast-growing economies such as Azerbaijan, Bangladesh, Indonesia, Senegal, Thailand, and Vietnam, among others. Structurally, BRICS might be an intergovernmental organization (IGO), but it does not suffer from supranational characteristics common to others such as the IMF and the World Trade Organisation. BRICS is a state-led process—it has the advantage of partial institutionalisation and a summit-based approach. Unlike its counterparts, such as the G7 and G20, BRICS is also willing to expand and this flexibility has attracted other developing countries who find it easier to negotiate at decentralised forums. Third, although the progress has been gradual, NDB has had some noteworthy successes—membership expansion, credit rating, and issuance of RMB bonds. NDB’s General Strategy for 2022–2026 further prioritises cohesive action and institutional assistance to member states to support their international commitments on the SDGs and Paris Agreement. BRICS also diversified its mandate to foster cooperation in areas of energy, transport, information and communication technology (ICT), and tourism.

NDB’s General Strategy for 2022–2026 further prioritises cohesive action and institutional assistance to member states to support their international commitments on the SDGs and Paris Agreement.

The backlash faced by BRICS for its inability to establish a global institutional model also stems from a reductionist understanding of seeing it as a replacement for existing structures. BRICS’ objective was not to replace, but to provide a counter coalition to emerging economies and address the disparity. As its membership increases, BRICS will move towards establishing a lobby of emerging and middle powers advocating for greater representation and reforms in the global financial institutions. While there are valid concerns that bilateral tensions within the group—such as strategic disagreements—could impact its functionality, these concerns need not dominate its agenda. Such differences can coexist with collaborative efforts on multilateral financial initiatives.

The way forward, thus, lies in de-hyphenating and focusing on BRICS as an economic coalition rather than a political alliance—it is possible to build multilateral consensus, especially in non – traditional areas such as sustainable development, climate, and inclusive growth. As the world grapples with the possibility of another global financial turmoil, BRICS, despite its challenges, might be the closest the Global South will get to establishing a functional multilateral financial institution.