For several years now, many of us have focused on the scourge of “fake news.” But much as we may blame avaricious social platforms and conniving public figures for driving widespread cynicism, we need to consider the role played by another more innocuous reality: misleading statistics.

Flagging confidence in both government and the mainstream media tracks decades in which official economic indicators—most notably those that purport to gauge the cost of living—have fundamentally failed to mirror middle-class reality.

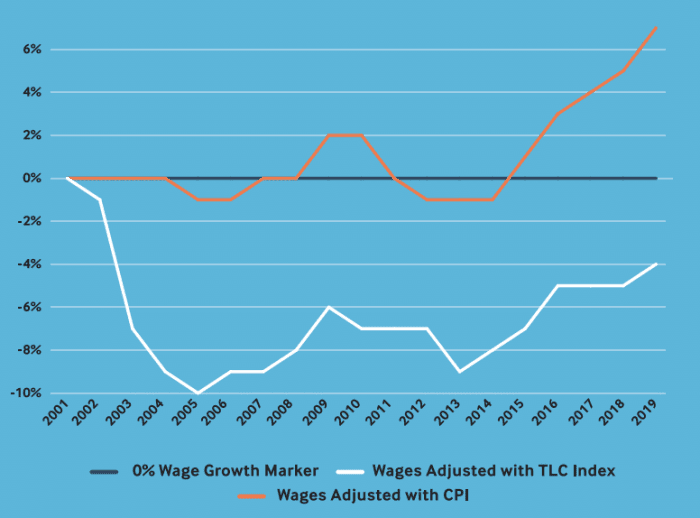

Perhaps “fake” is too strong a term to describe the data-driven consumer price index (CPI), which serves as the U.S. government’s proxy for inflation. But the narrative the CPI has long burnished—namely that, since 2000, ordinary expenses have been fairly manageable amid rising wages—is entirely debunked by new research.

Breaking news: U.S. inflation rate slows to 6.3%, Fed-favored PCE gauge shows, in a sign that price pressures could be peaking

CPI understates rising costs

Over the 20 years that preceded the present crisis, prices for things middle- and low-income Americans must purchase rose 40% beyond what CPI would indicate, more than wiping out a median earner’s income gains. In short, the CPI-driven narrative is something akin to “fake news.”

The implications are dire. Not so long ago, a family of four earning the median income in the United States could make ends meet with a little left over.

But, as a study done by the Ludwig Institute for Shared Economic Prosperity (LISEP) reveals, that’s no longer true. A two-income family—say, one where one parent works as an emergency-room technician and the other as a home-health aide—would at the median have had $4,000 extra to spend after covering their basic needs in 2001. Today, by contrast, that same family would have to go $2,000 into debt to sustain a very modest lifestyle.

Follow all the inflation news on MarketWatch

Percentage of families in the U.S. population with sufficient household income to meet all minimal adequate needs, 2001 and 2019, by family type. For example, more than 80% of families with two adults and no children could afford the basics in 2019, but less than 20% of single parents with three children could.

LISEP

Divorced from reality

That’s not to insinuate that the government is purposefully misleading the public. Rather, it suggests that the prevailing statistical methodology produces tragically misleading information for one clear reason: Prices for yachts, luxury hotel rooms, and other high-end items have risen much more modestly than the everyday items—food, housing, medical bills—that middle-class families are compelled to cover.

So the CPI’s heavy weighting of those luxury goods divorces it from the inflationary reality it purports to track.

Oddly enough, conventional wisdom within the world of economics isn’t that the government’s prevailing indicator understates inflation—but rather that the figure overstates it. For decades, many have worried that CPI fails to account for the possibility that consumers would find substitutes for more expensive products rather than accept a higher price. More recent studies have argued that CPI does not properly account for technological change.

But between 2001 and 2020, rents shot up by 150% at the same time CPI’s measure of housing costs grew by a mere 54%. Is it any wonder, then, why so many Americans sense that their plight is invisible to the people in charge?

Median wages adjusted for the CPI (orange line) show healthy increases in the past two decades but have been falling (white line) when adjusted for the True Living Cost index.

LISEP

Failure of fiscal policy

None of this is to absolve those who have cynically exploited American skepticism by stirring various pots or spreading false conspiracies. Nor is it to argue that the Federal Reserve should pursue a monetary policy different from what the board of governors might be inclined to employ given more traditional indicators. Today’s situation is real, and policy makers should work in concert, as President Joe Biden has proposed, to curtail the price increase borne primarily from the supply-chain bottleneck and the war in Ukraine.

But what has now been revealed as a more endemic divergence between CPI and a more accurate measure of middle-class inflation suggests that our fiscal policy has over the decades failed to ensure that successive generations of Americans have equal opportunity to enjoy the fruits of upward mobility.

Bad statistics have shrouded a worrisome economic reality that affects not only the poor and working class, but those earning median incomes as well. And once today’s crisis is stabilized, Washington should be focused squarely on rectifying that oversight.

Those of us who believe a responsible civic discourse rests on broad public understanding of the real world should stand strong against those who would exploit misinformation to serve their own interests. But we should also acknowledge reality. Purveyors of what is supposed to be good, fact-based, information have done us no favors by championing statistics born in some unreality. And the fact that government statistics have inadvertently done more to hide than reveal the extent to which America’s middle class has been hollowed out suggests we need to rethink the way we understand the world as it is.

Eugene Ludwig, a former U.S. comptroller of the currency, is chair of the Ludwig Institute for Shared Economic Prosperity and author of “The Vanishing American Dream.“

Other viewpoints on the impact of inflation

Rex Nutting: Inflation inequality is hitting the working class harder than at any other time on record

Seta Tutundjian: Climate change, the pandemic and now war in Ukraine have pushed hundreds of millions of hungry people to the brink

Mohamed El-Erian: The people in the global penthouse should worry about the ‘little fires everywhere’ in the basement