Sign up for CNN’s Wonder Theory science newsletter. Explore the universe with news on fascinating discoveries, scientific advancements and more.

The spacecraft performed a flyby of the dwarf planet and its moons in July 2015, and the insights gathered then are still rewriting nearly everything scientists understand about Pluto.

Pluto was relegated to dwarf planet status in 2006 when the International Astronomical Union created a new definition for planets, and Pluto didn’t fit the criteria.

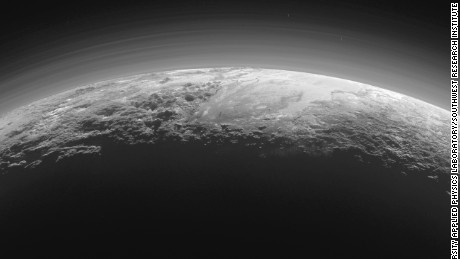

The dwarf planet exists on the edge of our solar system in the Kuiper Belt, and it’s the larger of the many frozen objects there orbiting far from the sun. The icy world, which has an average temperature of negative 387 degrees Fahrenheit (negative 232 degrees Celsius), is home to mountains, valleys, glaciers, plains and craters. If you were to stand on the surface, you would see blue skies with red snow.

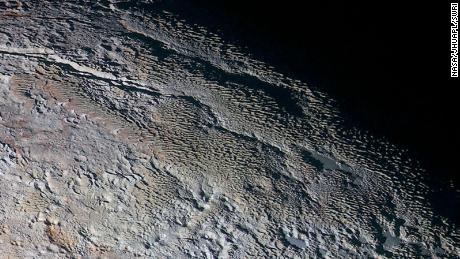

A new photo analysis showed a bumpy region on Pluto that doesn’t look like any other part of the small world — or the rest of our cosmic neighborhood.

“We found a field of very large icy volcanoes that look nothing like anything else we have seen in the solar system,” said study author Kelsi Singer, senior research scientist at the Southwest Research Institute in Boulder, Colorado.

A study detailing the findings published Tuesday in the journal Nature Communications.

The region is located southwest of the Sputnik Planitia ice sheet, which covers an ancient impact basin stretching 621 miles (1,000 kilometers) across. Largely made of bumpy water ice, it’s filled with volcanic domes. Two of the largest are known as Wright Mons and Piccard Mons.

Wright Mons is about 13,123 to 16,404 feet (4 to 5 kilometers) tall and spans 93 miles (150 kilometers), while Piccard Mons reaches about feet 22,965 feet (7 kilometers) high and is 139 miles (225 kilometers) wide.

Wright Mons is considered to be similar in volume to the Mauna Loa volcano in Hawaii, which is one of the biggest volcanoes on Earth.

Some of the domes observed in the images merge together to form even bigger mountains, Singer said. But what could have created them? Ice volcanoes.

Ice volcanoes have been observed elsewhere in our solar system. They move material from the subsurface up to the surface and create new terrain. In this case, it was water that quickly became ice once it reached the frigid temperatures of Pluto’s surface.

“The way these features look is very different than any volcanoes across the solar system, either icy examples or rocky volcanoes,” Singer said .”They formed as mountains, but there is no caldera at the top, and they have large bumps all over them.”

While Pluto has a rocky core, scientists have long believed that the planet lacked much interior heating, which is needed to spur volcanism. To create the region Singer and her team studied, there would have been several eruption sites.

The research team also noted that the area doesn’t have any impact craters, which can be seen across Pluto’s surface, which suggests that the ice volcanoes were active relatively recently — and that Pluto’s interior has more residual heat than expected, Singer said.

“This means Pluto has more internal heat than we thought it would, which means we don’t fully understand how planetary bodies work,” she said.

The ice volcanoes probably formed “in multiple episodes” and were likely active as recently as 100 million to 200 million years ago, which is young geologically speaking, Singer added.

If you were to witness an ice volcano erupt on Pluto, it might look a little different than you expect.

“The icy material was probably more of a slushy mix of ice and water or more like toothpaste while it flowed out of a volcanic vent onto the surface of Pluto,” Singer said. “It is so cold on the surface of Pluto that liquid water cannot remain there for long. In some cases, the flow of material formed the massive domes that we see, as well as the lumpy terrain found everywhere in this region.”

When New Horizons flew by this region, the team didn’t witness any current ice volcano activity, but they were only able to see the area for about a day. It’s possible that the ice volcanoes are still active.

“They could be like volcanoes on Earth that remain dormant for some time and then are active again,” she said.

Pluto once had a subsurface ocean, and finding these ice volcanoes could suggest that the subsurface ocean is still present — and that liquid water could be close to the surface. Combined with the idea that Pluto has a warmer interior than previously believed, the findings raise intriguing questions about the dwarf planet’s potential habitability.

“There are still a lot of challenges for any organisms trying to survive there,” Singer said. “They would still need some source of continual nutrients, and if the volcanism is episodic and thus the heat and water availability is variable, that is sometimes tough for organisms as well.”

Investigating Pluto’s intriguing subsurface would require sending an orbiter to the distant world.

“If we did send a future mission, we could use ice-penetrating radar to peer directly into Pluto and possibly even see what the volcanic plumbing looks like,” Singer said.