Thanks to the pandemic, teams are more distributed than ever. For some companies, that’s led to a disconnect between lower-level employees and leadership, the latter of whom are generally skeptical of remote work. According to a survey from GoodHire, 75% of managers want workers in the office, citing the potential lack of focus and loss of company culture. But in a separate poll by McKinsey, 87% of workers said that they would embrace the opportunity to work remotely when given the choice.

Micah Remley, the CEO of Robin, argues that businesses can have their cake and eat it too by going the “hybrid” work route — that is, having employees work in-office during a portion of the week and remote for the remainder. Remley joined Robin after Brian Muse and twin brothers Sam and Zach Dunn founded the startup to help companies manage office space using reservation software.

“We want C-suite leaders, facilities, and IT teams to realize that vibrant hybrid workplaces don’t involve complicated technology or elaborate rollout plans,” Remley told TechCrunch in an email interview. “Something that resonates with every leader is that our platform removes barriers from coming into the office and creates a workplace centered on choice. When employees have a choice, returning to the office becomes less about mandates and more about connection.”

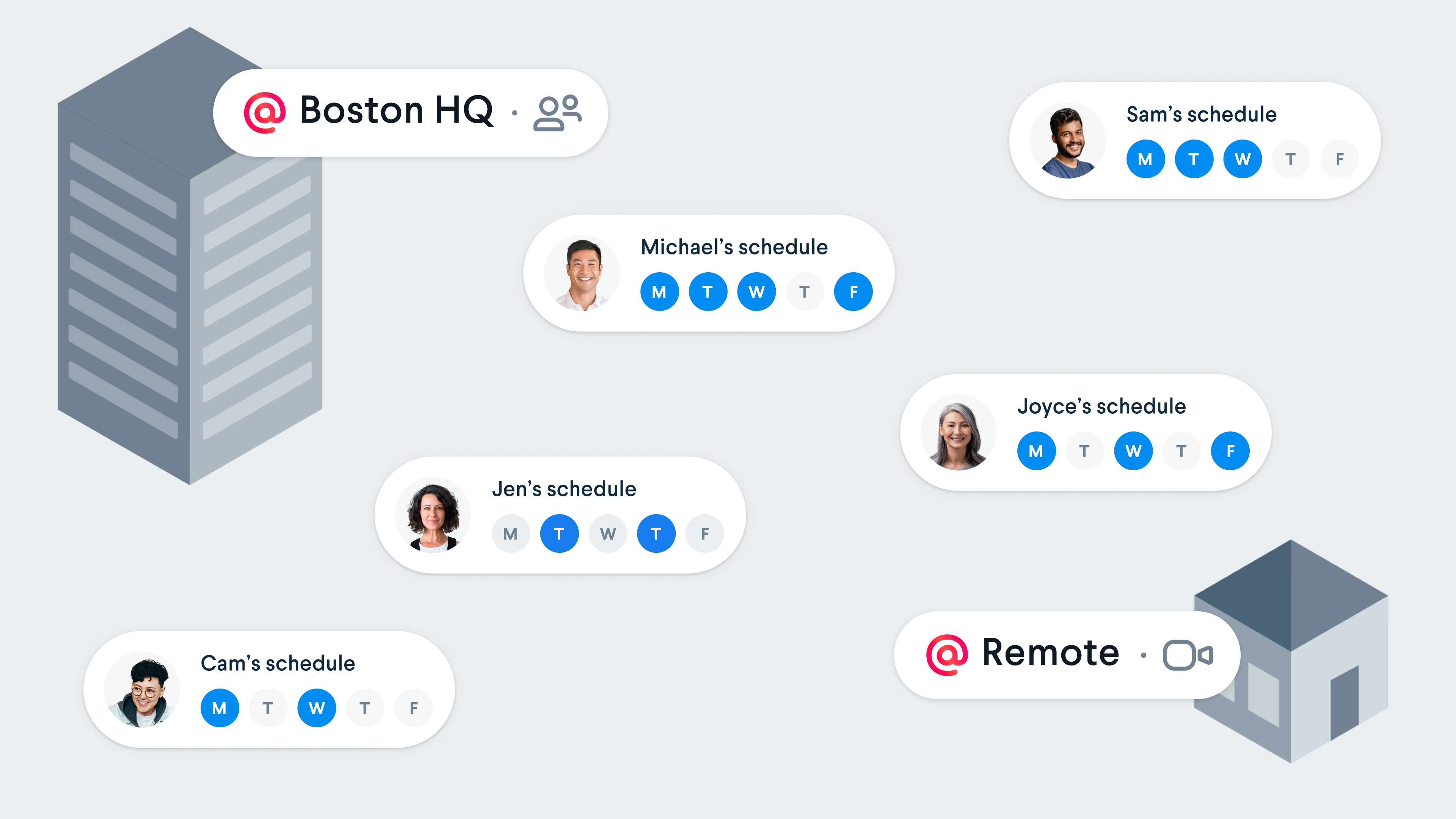

Launched in 2014, Robin began as a conference room scheduling app. But over the past 8 years, the platform has expanded to handle various aspects of desk booking, room reservation and guest management. Accessing Robin on the web or mobile, workers can request rooms, desks and equipment before they arrive at an office. Customers who opt for Robin’s guest check-in features can use the platform to have visitors submit any paperwork, like waivers and NDAs, required under the office’s policy.

Image Credits: Robin

Remley pitches Robin as a means of tracking office usage over time as well. On the back end, managers can see how people are using different spaces and tap a calculator to figure out the ideal number of seats, desks and collaborative spaces for a given floor. A newer capability, the “Global Hybrid Trends Dashboard,” shows usage statistics from other companies of the same size, sector and region, providing points of reference.

“Robin combines your favorites, your team, and the people you meet with most to deliver intelligent recommendations on when to come to the office, and takes the pain out of planning by auto-suggesting desks and spaces near your colleagues,” Remley said. “Office utilization analytics gives admins visibility on who is using the office, when they are using it, and which spaces are most commonly used. As companies’ headcount evolves over time, Robin helps customers understand how to optimize their space for the changing times.”

Some workers might not be comfortable with that level of tracking. Robin says that it anonymizes usage data, aggregating it across spaces, floors and buildings. But it’s unclear to what extent the platform does so. We’ve asked Remley for clarification.

Besides competing against office scheduling startups like Envoy, Officely and OfficeRnD, Robin’s major challenge is proving that hybrid work has staying power. According to a TinyPulse study, more than 80% of HR leaders believe hybrid setups to be more exhausting for employees than remote or entirely in-office schedules. Some segments of the workforce are less bullish about hybrid compared to others — Deloitte recently found that over half of women who combine remote and in-office work “have already experienced a lack of flexibility in their working patterns or are concerned this will happen in the future.” But many of the logistical issues around hybrid affect everyone, like balancing staff that comes into the office with the staff that stays at home.

As a piece in Computerworld points out, hybrid work can become a “minefield of unfairness,” rewarding people who are more able and willing to work in the office. In a Gartner poll, 59% of women knowledge workers — who, the poll found, are more likely than men to express a preference for remote work — think in-office employees will be seen as higher performers while 78% believe in-office workers are more likely to be promoted.

Image Credits: Robin

Remley pushes back against the notion that hybrid work is doomed to fail. Software like Robin, he asserts, can give companies the data they need to arrive at a work strategy that pleases most — if not all, admittedly — employees. In any case, the startup hasn’t had trouble lining up customers. Remley says that thousands of teams, including in militaries and governments and at brands like Toyota, Twitter, Mailchimp and Peloton, use Robin to organize their work.

In a vote of investor confidence, Robin today closed a $30 million Series C round led by Tola Capital with participation from Firstmark, Accomplice, Boldstart and Allegion Ventures. Remley says that the capital — which brings Robin’s total raised to more than $59 million — will be put toward platform development, international expansion and growing Robin’s over-190-person headcount.

“Robin has always focused on the hybrid work experience, knowing that eventually, workplaces would shift in that direction. The pandemic accelerated that shift faster than anyone could have predicted,” Remley said. “As companies focus on getting leaner, hybrid work becomes even more attractive as a cost-saving measure. Many of our clients reduced their commercial real estate footprint over the past two years and we expect that to continue. We don’t foresee a broad return to the office in the way we used to think of work … Employees don’t want that, and even in a recession environment, doing a total return to the office doesn’t make economic sense.”