We wrote some years back that there were seriously rotten things afoot in unicorn-land and venture capital generally. That assessment is now borne out by a new Bloomberg story by Kate Root, The Unicorn Boom Is Over, and Startups Are Getting Desperate, touted by Bloomberg’s Matt Levine in The Unicorns Are Zombies. The short version is that not only did nearly all of these once hyped companies fail to make exits (then expected to be via IPO) and seem pretty certain to be unable to do so now at deemed-adequate prices, but many look set to eventually have to shut operations or radically downsize.

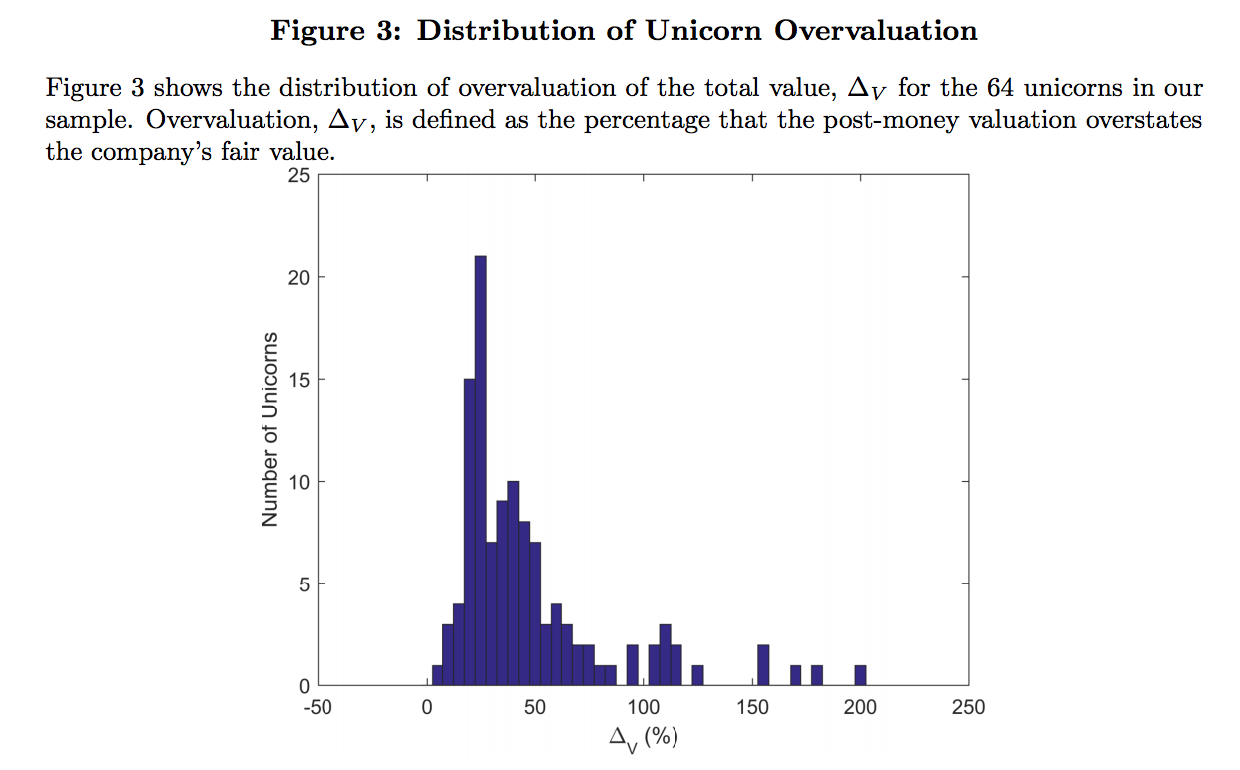

The reason this is no surprise is that investors conned themselves in the unicorn bubble. For instance, from a 2017 post, Fake Unicorns: Study Finds Average 49% Valuation Overstatement; Over Half Lose “Unicorn” Status When Corrected, based on the in-depth work of economists Will Gornall and Ilya Strebulaev, we unpacked the wild overvaluation of unicorns.

And by wild overvalution, we did not mean investors being willing to pay more than even an optimistic reading of their prospects suggested. This instead was a remarkable failure of basic competence: of investors using flattering valuation rules of thumb as opposed to analyzing what various of the multiple classes of equity of privately issued equity were worth. From that post:

A recent paper by Will Gornall of the Sauder School of Business and Ilya A. Strebulaev of Stanford Business School, with the understated title Squaring Venture Capital Valuations with Reality, deflates the myth of the widely-touted tech “unicorn”. I’d always thought VCs were subconsciously telling investors these companies weren’t on the up and up via their campaign to brand high-fliers with valuations over $1 billion as “unicorns” when unicorns don’t exist in reality. But that was no deterrent to carnival barkers would often try to pass off horses and goats with carefully appended forehead ornaments as these storybook beasts. The Silicon Valley money men have indeed emulated them with valuation chicanery.

Gornall and Strebulaev obtained the needed valuation and financial structure information on 116 unicorns out of a universe of 200. So this is a sample big enough to make reasonable inferences, particularly given how dramatic the findings are.1 From the abstract:

Using data from legal filings, we show that the average highly-valued venture capital-backed company reports a valuation 49% above its fair value, with common shares overvalued by 59%. In our sample of unicorns – companies with reported valuation above $1 billion – almost one half (53 out of 116) lose their unicorn status when their valuation is recalculated and 13 companies are overvalued by more than 100%.

Another deadly finding is peculiarly relegated to the detailed exposition: “All unicorns are overvalued”:

The average (median) post-money value of the unicorns in the sample is $3.5 billion ($1.6 billion), while the corresponding average (median) fair value implied by the model is only $2.7 billion ($1.1 billion). This results in a 48% (36%) overvaluation for the average (median) unicorn. Common shares even more overvalued, with the average (median) overvaluation of 55% (37%).

How can there be such a yawning chasm between venture capitalist hype and proper valuation?

By virtue of the financiers’ love for complexity, plus the fact that these companies have been private for so long, they don’t have “equity” in the way the business press or lay investors think of it, as in common stock and maybe some preferred stock. They have oodles of classes of equity with all kinds of idiosyncratic rights. From the paper:

VC-backed companies typically create a new class of equity every 12 to 24 months when they raise money. The average unicorn in our sample has eight classes, with different classes owned by the founders, employees, VC funds, mutual funds, sovereign wealth funds, and strategic investors…

Deciphering the financial structure of these companies is difficult for two reasons. First, the shares they issue are profoundly different from the debt, common stock, and preferred equity securities that are commonly traded in financial markets. Instead, investors in these companies are given convertible preferred shares that have both downside protection (via seniority) and upside potential (via an option to convert into common shares). Second, shares issued to investors differ substantially not just between companies but between the different financing rounds of a single company, with different share classes generally having different cash flow and control rights.

Determining cash flow rights in downside scenarios is critical to much of corporate finance, and the different classes of shares issued by VC-backed companies generally have dramatically different payoffs in downside scenarios. Specifically, each class has a different guaranteed return, and those returns are ordered into a seniority ranking, with common shares (typically held by founders and employees, either as shares or stock options) being junior to preferred shares and with preferred shares that were issued early frequently junior to preferred shares issued more recently.

In other words, unlike the hopefully very liquid shares of public companies that many own, all fungible with those of other stockholders, each class of equity in these unicorns is bespoke, with different rights in the case of investment success and shortfall.

We teased out further implications of the Gornall/Strebulaev analysis in a 2018 New York Magazine article, Fake ‘Unicorns’ Are Running Roughshod Over the Venture Capital Industry. From that article:

You might think that a study demonstrating that venture capital-funded “unicorns” are overvalued, and by a stunning 48 percent on average, would shake up the industry. Yet “Squaring Venture Capital Valuations With Reality,” a paper announcing just that finding by Will Gornall and Ilya A. Strebulaev (professors at the Sauder School of Business at the University of British Columbia and the Stanford Graduate School of Business, respectively), received only a perfunctory round of coverage from some important investment and tech publications when it was published.

It’s no surprise that a study casting doubt on the worth of darlings like Lyft and Cloudflare didn’t move investors or change the venture capital industry. Trade press reporters don’t have much of a future if they take to biting the hands that feed them, and the investors with overpriced wares don’t want to admit they’ve been had, or, worse, that they’re part of the problem. But write-ups of this important paper, with its sensational finding, missed that the authors’ analysis is deadly for the venture capital industry as a whole.

The median venture capital fund loses money. Only the top 5 percent of funds earn enough to justify the risks of investing in venture capital. The nature of venture capital is that the performance of those few successful funds in turn rests on the spectacular results of a small fraction of the investments in a particular fund. Gornall and Strebulaev’s finding that the performance of the winners — and even the also-rans — is overstated further undermines the already strained case for investing in venture capital. If you are Joe Retail and think this isn’t your problem, think twice. If you invested in high-growth mutual funds, your holdings probably include shares in large venture-capital-backed private companies.

And now the caliber of the downside protection in these supposedly well-negotiated classes of private stock are about to be tested. Key sections from the Kate Root Bloomberg account:

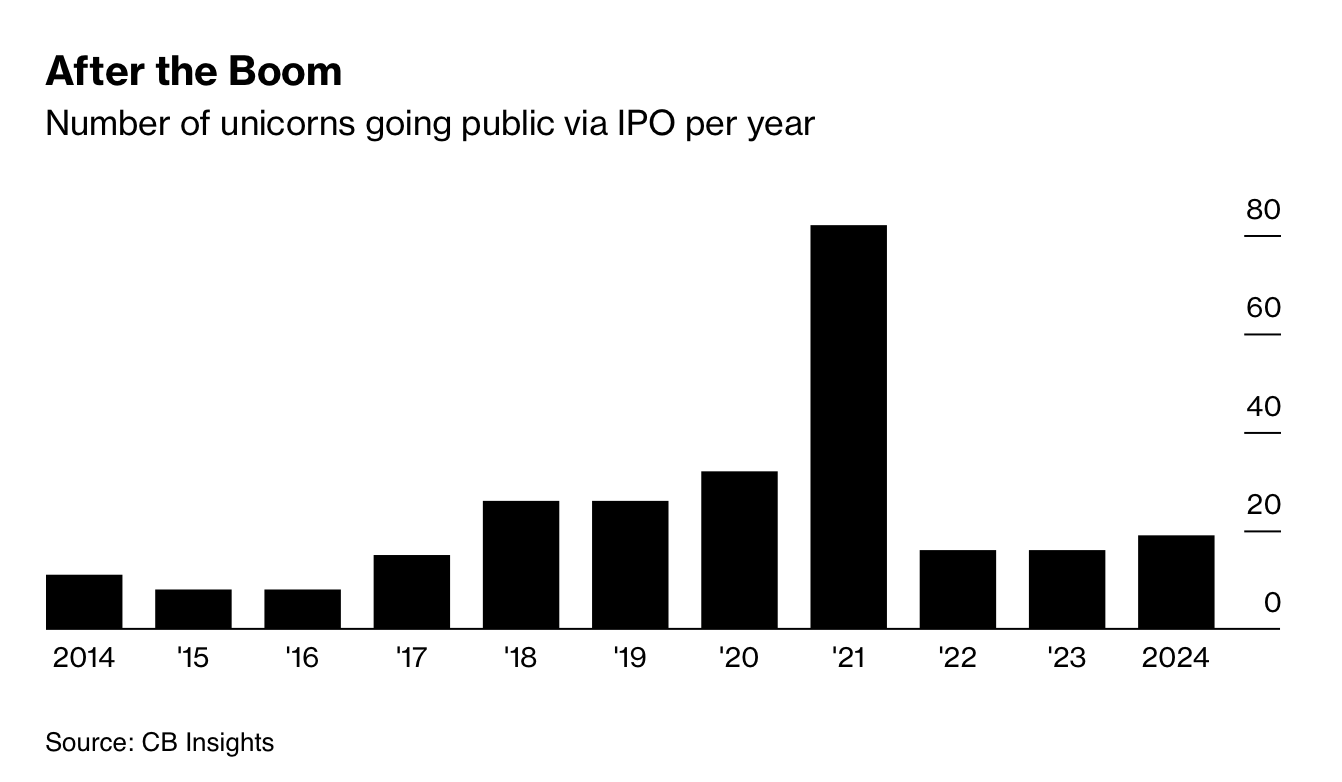

By the time the Covid-era tech boom crested in 2021, well over 1,000 venture capital-backed startups had reached valuations above $1 billion, including fake meat purveyor Impossible Foods Inc., home maintenance marketplace Thumbtack and online-class platform MasterClass. Then came a squeeze sparked by rising interest rates, a slowing initial public offering market and the feeling that any startup not focused on AI was yesterday’s news….

In 2021 more than 354 companies received billion-dollar valuations, thus achieving unicorn status. Only six of them have since held IPOs, says Ilya Strebulaev, a professor at Stanford Graduate School of Business. Four others have gone public through SPACs, and another 10 have been acquired, several for less than $1 billion. Others, such as the indoor farming company Bowery Farming and AI health-care startup Forward Health, have gone under. Convoy, the freight business valued at $3.8 billion in 2022, collapsed the following year; the supply chain startup Flexport bought its assets for scraps….

Welcome to the era of the zombie unicorn. There are a record 1,200 venture-backed unicorns that have yet to go public or get acquired, according to CB Insights, a researcher that tracks the venture capital industry. Startups that raised large sums of money are beginning to take desperate measures. Startups in later stages are in a particularly difficult position, because they generally need more money to operate—and the investors who’d write checks at billion-dollar-plus valuations have gotten more selective. For some, accepting unfavorable fundraising terms or selling at a steep discount are the only ways to avoid collapsing completely, leaving behind nothing but a unicorpse.

“Unicorpse”! Continuing:

Many startups, though, were built to chase growth with little concern for near-term profitability in their early years, assuming they could continue fundraising at increasing valuations. In many cases, that formula no longer works. Fewer than 30% of the unicorns from 2021 have raised financing in the past three years, according to data provided by Carta Inc., a financial technology company working with startups. Of those, almost half have done so-called down rounds, where investors value their companies at lower levels than they’d received in the past.

One of the big risks of the enthusiasm for venture capital was the assumption that the market for IPOs which provide valuation benchmarks for other exits, would remain accessible. Protracted super low interest rates resulted in investors reaching for return, and thus risk, which was not a sound investment proposition if you didn’t get out before the window of permissiveness closed. When I was a kid at Goldman, the rule of thumb was that the IPO market was accessible to young technology companies only about two years out of five, so that venture-backed plays needed to have enough cash or access to funds so as to catch those opportunities.

And please do not attempt to defend venture capital firms. Fewer than 1% of startups get venture funding, according to the careful work of Amar Bhide. And they weren’t essential to the performance of the highest-growth companies. One of my past lawyers, who represented a lot of inventors, strongly advised them to get money anywhere other than venture capital: friends, family, vendors, customers. She’d seen too many of the original managements teams have their companies taken from them by the moneybags. In keeping with her view, only 25% of the Inc. 500 was venture capital funded. And that total includes quite a few cases where the high-growth private company had grown big enough to do an IPO, but investment bankers recommended a late venture capital funding round. Being able to tout top names like Kleiner Perkins or Sequoia as backers would produce a higher valuation, enough to offset the dilution of a share sale.

And let’s not forget that venture capital is not a good deal for limited partners either. From a 2023 post, “Venture Capital Funds Are Mostly Just Wasting Their Time and Your Money”:

This deliciously-titled Financial Times story recaps a new study by Morgan Stanley equity strategists Edward Stanley and Matias Øvrum which provides a devastating takedown of the venture capital industry’s claim to making money for investors, as opposed to just themselves. The overarching finding is that venture capital funds typically don’t outperform stocks, and that’s before getting to the fact that it is pretty much impossible to pick venture capital winners (more on that shortly). Oh, and because venture capital is riskier than investing in equities, investors oughts to get better returns than if they just bought some index funds.

Mind you, this is hardly a new idea. The Economist pointed out some years ago, based on a different large-scale study, that venture capital funds only meet equity returns with a lot more fees and risks. Harvard professor Josh Lerner said as much in a 2015 presentation to CalPERS’ board, except he pointed out that to the extent the industry could claim to outperform, it was in the top 10% of the funds. Lerner insinuated that there might be a secret sauce for that; a one-time newbie on the HBS faculty had Lerner tell him how to get lucrative consulting gigs advising public pension funds on this Mission Impossible. As we wrote in 2014:

When you boil it down, this graph illustrates the ugly truth of investing in private equity: it’s not attractive unless you can outrun most of your peers investing in the asset class.

Rather than question the logic of investing in private equity at all, everyone in the industry has convinced themselves that it is reasonable to believe that they can be the Warren Buffett of private equity. The investment consultants go through the shooting-fish-in-a-barrel exercise of convincing their institutional clients that each of them is prettier, smarter, and more charming than average, and therefore capable of achieving sparking results. Needless to say, flattery is an easy sell…

Fundamentally, this is an intellectually dishonest exercise, and diametrically opposed to the way many public pension funds construct other parts of their investment portfolios. With public equity in particular, it’s almost certain that a significant majority of U.S. pension fund assets are invested in index funds. That’s because pension funds have recognized that, collectively, they cannot do better than average, and that after paying active management fees, actively managed public equity portfolios typically perform worse than the market average.

So it’s not as if these investors are so clueless that they can’t grasp the point that all of them cannot achieve above average results, let alone significantly above average results. Instead, with private equity, there is a desperate desire to be in the asset class for reasons that probably reflect a combination of intellectual capture by the PE managers, political corruption in legislatures that control public fund board appointees, and the need to have a strategy that could conceivably solve the pension underfunding problem over time.

Mind you, the “see if you can out-invest your competitors” problem is more acute in venture because outperformance is concentrated in so few funds.

Why are we belaboring this history before getting to a juicy paper? Because the bad facts about venture capital are, or should be, well known. But it’s just so much fun to talk to those venture capital mavens about all the great sexy things they invest in, even if the vulture, um, venture capitalists spend too much money finding and baby-sitting their charges, and most come a cropper anyhow.

Investors really do fall sucker to private equity and venture capital patter about their big game hunting of companies (and the remarkable investor permissiveness in allowing them to assign their own valuations of investee companies). Notice how hedge funds have to some degree fallen out of favor due to what ought to be recognized as the same basic problem, too much fee and expense extraction relative to any ability to outperform (“generate alpha”)? That’s because private equity and venture capital partners and sales staff are charismatic and manipulative, while really good hedges are often geeks. And even when not, it’s hard to make an explanation of your quant-y investment method sound sexy. Instead, hedgies tend to induce MEGO (“My Eyes Glaze Over”), which is hardly an inducement for writing big checks.

So even though investors have had decades to figure this scam out, it remains an exercise in hope over experience.