By Lambert Strether of Corrente.

One of my flaws as a debater on the negative side was that I found it difficult to prepare for cases that I thought were really, really stupid. As a result, my rebuttals were not as crisp as they might have been. It may well be that the same bad attitude has carried over into my coverage of New York prosecutor Alvin Bragg’s oft-misnomered “hush money” care, People vs. Donald J. Trump. The good news is that in the course of researching for this case, I found the docket — thanks, Google. Not! — and so now I can go through all the filings, and better yet, the transcripts, before the verdict finally arrives. At last being able to do the reading will be a great relief to me and possibly to you, since news coverage has been utterly miserable, childishly personality-driven (unlike Colorado vs. the United States, which had legal minds from across the spectrum doing serious analysis although, to be fair, of another stupid case).

However, People v. Trump is not only stupid (and it is often stupid in the complex ways that certain operatives are stupid), it is bewildering and befogged. It feels like a good deal of the action has been taking place off-stage, and so it’s hard to blame even well-intentioned reporters for being confused. Take this oft-repeated talking point, with Byron York at the Washington Examiner giving a example:

Perhaps the weirdest, and by far the most unjust, thing about former President Donald Trump’s trial in New York is that we do not know precisely what crime Trump is charged with committing. We’re in the middle of the trial, with Trump facing a maximum of more than 100 years in prison, and we don’t even know what the charges are! It’s a surreal situation.

Surreal indeed, but what York writes is not quite true; Bragg had four (4) theories of the case, that is, four charges (now he has three (3) but we’ll get to that). However, as we shall see, these theories have been presented in filings, and seem not to have been presented in open court, or presumably they would have been reported on.

Bragg’s architecture in People vs. Trump is what Just Security editor Asha Rangappa amusingly labeled a “felony bump-up,” described by Andrew McCarthy:

As we’ve noted many times, the actual charge against Trump (multiplied into 34 felonies by Bragg) is falsification of business records with fraudulent intent. That is a substantive offense, not a conspiracy (i.e., to be guilty, you actually have to carry out the criminal act, not just agree to do it). Business-records falsification is normally a misdemeanor under New York law (§175.05) but it can be inflated into a felony — with a prison sentence of up to four years for each offense — if prosecutors can prove that the defendant’s fraudulent intent included the concealment of “another crime.”

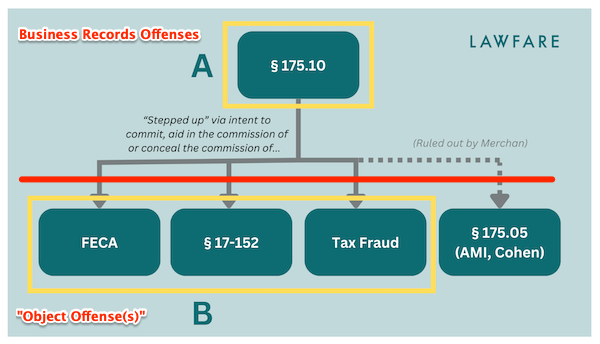

So, as we showed in NC here, there are two layers to People vs. Trump: The Business Records Offense, and the “Object Offense.”[1] By itself, the business records offenses are misdemeanors; only when they are combined with one or more object offenses — Bragg’s theories of the case — do they become felonies (although, amusingingly, the object offense(s) can also be misdemeanor(s)).

Because I have not yet done the reading, this post will be informative, rather than analytical; I will look at the state of play using Bragg’s architecture. This is in itself newsworthy! First, I will look at the business records offenses, and then at the object offenses. I will then address the election conspiracy aspect of the case, then Molineux Rule, and conclude.

The Business Records Offenses

The business records offenses are accurately described by Andrew McCarthy:

Just to remind you, the allegation in the indictment is that Trump fraudulently caused his business records to be falsified eleven years after this encounter [between Stormy Daniels and Trump]. The encounter makes no difference to the proof of the charges. The state’s theory is that Trump’s records are false because they described as ongoing ‘legal services’ what was actually the reimbursement of a debt to Trump’s lawyer [Michael Cohen] (in connection with a legal transaction in which the lawyer did, in fact, represent Trump). Whether the debt arose out of paying Stormy for an NDA or some other obligation is of no moment to the question of whether the book entry ‘legal services’ accurately describes the payments to Cohen.

Here again my bias against stupid arguments may be working against me. That said, Cohen was lawyer and a fixer. Are we really really going to argue about whether a fixed performed “legal services” or not? (This argument reminds of Engoron’s view that there was only one real estate investor in Manhattan who ever engaged in puffery: Donald Trump.)

The “Object Offense(s)”

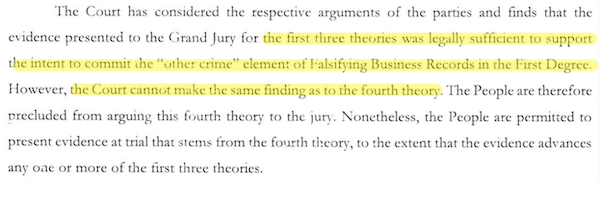

Let’s start with the text of Judge Merchan’s “Decision & Order, Feb. 15, 2024” (this seems to be in response to a Motion to Dismiss from the Trump team, but that’s not on the docket, at least not earlier than the Decision and Order, as I would expect to be):

As you can see, the People (Bragg) have four theories for the “object offense.” Merchan then throws out the fourth, leaving three:

(Oddly, it seems that Merchan, in his decision and order, is doing a good deal of tidying up and summarizing of Bragg’s brief responding to Trump’s Motion to Dismiss; it’s almost like he’s directing Bragg on how to present his case.) Here, depressingly, is a diagram from Brookings Institution-adjacent entity Lawfare that summarizes the state of Bragg’s architecture[2] (I’ve added some helpful annotations in red):

Let’s go through each layer in turn. On § 175.10, the statute reads:

A person is guilty of falsifying business records in the first degree when he commits the crime of falsifying business records in the second

degree, and when his intent to defraud includes an intent to commit another crime [the “object offense”] or to aid or conceal the commission thereof.

McCarthy comments:

Yet, in his major pre-trial ruling, Merchan endorsed Bragg’s theory that because §175.10 says “another crime” rather than “another New York crime,” there is no bar to Bragg’s endeavoring to prove that Trump was concealing a federal crime. (See Merchan’s pre-trial opinion, pp. 12–14.) By this loopy logic, Bragg similarly has jurisdiction to enforce, say, Chinese penal statutes, sharia’s hudud crimes, and perhaps even the criminal laws of Rome (after all, under the Bragg/Merchan rationale, the statute doesn’t say the “other crime” must still be in existence).

I don’t think that’s a bad argument; we’ll see how it goes on appeal (though, as we shall see, not all the object offenses are Federal).

So much for the business records layer. Now to the object offenses.

First, the Federal Election Campaign Act (FECA). McCarthy writes:

Judge Juan Merchan is orchestrating Trump’s conviction of a crime that is not actually charged in the indictment [none was]: conspiracy to violate FECA (the Federal Election Campaign Act — specifically, its spending limits). That should not be possible in the United States, where the Constitution’s Fifth Amendment mandates that an accused may only be tried for a felony offense if it has been outlined with specificity in an indictment, approved by a grand jury that has found probable cause for that offense.

Yet, Judge Merchan has swallowed whole Bragg’s theory that he can enforce FECA. The judge not only ruled pre-trial that Bragg could prove the uncharged federal crime; he has abetted Bragg’s prosecutors in their framing of the case for the jury as a “criminal conspiracy,” notwithstanding that no conspiracy is actually charged in the indictment — under either federal or state law. And although the trial has been under way for just a week, Merchan has already made key rulings patently designed to convince the jury that Trump’s complicity in a conspiracy to violate FECA has already been established.

LawFare comments:

Trump has leveled multiple legal challenges against Bragg’s use of FECA as an object offense, arguing in his motion to dismiss that a violation of federal law can’t serve as the “other crime” under § 175.10. Merchan, however, held it could. Trump also argued that FECA preempts state law and thus rules out prosecution under § 175.10 with FECA as the object offense. Merchan rejected this argument as well, relying on a ruling last July to that effect by Judge Alvin Hellerstein of the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York in the context of rejecting Trump’s attempt to remove this case to federal court.

I think “loopy,” as above, is a fair word here. Under Federalism, do we really want the States enforcing (and, presumably, interpreting) Federal Law? How about the Espionage Act? Or closer to home, the Public Health Service Act in the midst of a pandemic? Again, we’ll see how this fares on appeal[3].

Second, New York State Law § 17-152:

Conspiracy to promote or prevent election. Any two or more persons who conspire to promote or prevent the election of any person to

a public office by unlawful means and which conspiracy is acted upon by one or more of the parties thereto, shall be guilty of a misdemeanor.

(Note again that this can be the object offense, even if it’s a misdemeanor.) Bragg’s use of § 17-152 has been described as “novel” and “twisty.” From NC:

“Business Insider asked two veteran New York election-law attorneys — one a Republican, the other a Democrat — about the law, also known as ‘Conspiracy to promote or prevent election.’ Neither one could recall a single time when it had been prosecuted. Two highly respected law professors specializing in New York election law said the same…. However, while the two attorneys were highly skeptical of the DA’s newly focused strategy, the two election law professors told BI they were confident it would lead to a conviction. Sure, 17-152 has never been used before, they said. But that doesn’t mean it won’t work now that the dust has been blown off…. [Jeffrey M. Wice, who teaches state election law at New York Law School] noted that two judges — Merchan and Judge Alvin K. Hellerstein, a Manhattan federal judge who rejected Trump’s attempt to move the hush-money case to federal court — upheld the use of 17-152 in this case.” But wait! There’s more! “[W]hat if that underlying crime is section 17-152 — conspiring to mess with an election through ‘unlawful means?’ Things will get “twisty,” [Brooklyn attorney and former Democratic NY state Sen. Martin Connor] said, when prosecutors try to show that Trump’s falsified business records are felonies because of an underlying crime — 17-152 — that itself needs proof of a conspiracy to do something ‘unlawful.’ ‘You’re having an underlying crime within an underlying crime to get to that felony,’ Connor told BI. ‘It’s novel,” he said with a laugh. ‘It’s novel,” he repeated. Section 17-152 needs its own underlying criminal conspiracy, he said. ‘Two or more conspiring to elect or defeat a candidate — that’s the definition of every political campaign,’ he joked. ‘It’s only when you conspire to do it by unlawful means that you violate this law.’ Having an election-conspiracy statute like 17-152 on the state election-law books makes little sense, he said. ‘It would appear to cover something like three people getting together and saying, ‘Let’s break into our opponent’s headquarters and destroy all his equipment,’ Connor said.”

Lawfare expands on “twisty”:

During opening statements on April 22, prosecutor Matthew Colangelo emphasized the role of § 17-152 in the district attorney’s case, declaring, “This was a planned, coordinated long-running conspiracy to influence the 2016 election, to help Donald Trump get elected.” Senior Trial Counsel Joshua Steinglass further underlined the importance of the statute the following day, describing § 17-152 as “the primary crime that we have alleged” as an object offense. “The entire case is predicated on the idea that there was a conspiracy to influence the election in 2016,” Steinglass said.

But § 17-152 requires that a conspiracy be carried out by “unlawful means”—so what “unlawful means” is Bragg alleging? Here, the legal theory loops back around to point to the other three potential object offenses: FECA violations, tax fraud, and AMI’s and Cohen’s misdemeanor falsifications of business records under § 175.05.

Third, tax fraud. Lawfare comments:

The potential tax fraud arises from the particular method by which the Trump Organization reimbursed Cohen for his payments to Daniels. Bragg alleges that “defendant reimbursed Cohen twice the amount he was owed for the payoff so Cohen could characterize the payments as income on his tax returns and still be left whole after paying approximately 50% in income taxes.” Here, Bragg points to federal, state, and local prohibitions on providing knowingly incorrect tax information.

The twist here is that because Cohen reported his income as greater than it actually was, he paid more in taxes, rather than less—which is probably not what most people have in mind when they think of tax fraud. On this point, Bragg argues that “[u]nder New York law, criminal tax fraud in the fifth degree does not require financial injury to the state” and that “[f]ederal tax law also imposes criminal liability in instances that do not involve underpayment of taxes.” Merchan seems to have been convinced, rejecting Trump’s argument “that the alleged New York State tax violation is of no consequence because the State of New York did not suffer any financial harm.” He does not explain further, simply writing, “This argument does not require further analysis.”

I’m totally not a tax lawyer, so I can’t express a view (but I imagine it’s likely that there will be a member of the jury who was prosecuted by the IRS for paying too much tax).

Fourth, § 175.05. This is the National Enquirer “catch and kill scheme” that so dominated early coverage of the trial, when David Pecker was a witness; Merchan tossed it out as an object offense, though as Lawfare notes:

Note that while Merchan ruled out these third-party § 175.05 violations as object offenses for Trump’s violation of § 175.10, they’re still available to Bragg as a means by which to get to § 17-152.)

(Lawfare also has an interesting discussion of whether, if Bragg presents all three remaining theories, the jury has to agree on all three, and what the burdens of proof for each are.)

Election Conspiracy

Matthew Colangelo, now working in Bragg’s office, formerly deputy director of the president’s National Economic Council, chief of staff at the Department of Labor, deputy assistant attorney general in the DOJ’s Civil Rights Division, and a campaign consultant for the DNC, opened People vs. Trump as follows. From the transcript (I’ve added some helpful notes), the very beginning of the case:

This case is about a criminal conspiracy[1] and a cover-up. The defendant, Donald Trump, orchestrated a criminal scheme to corrupt the 2016 presidential election[2]; then he covered up that criminal conspiracy by lying in his New York business records over and over and over again. In June of 2015, Donald Trump announced his candidacy for president in the 2016 election; a few months later this conspiracy began. He invited his friend, David Pecker, to a meeting at Trump Tower here in Manhattan. Mr. Pecker was the CEO of a media company that, among other things, owned and published the National Enquirer tabloid. Michael Cohen was also at that meeting. He worked for the defendant as the defendant’s special counsel at his company, the Trump Organization. And those three men formed a conspiracy at that meeting to influence the presidential election by concealing negative information about Mr. Trump[3] in order to help him get elected. As one part of that agreement, Michael Cohen paid $130,000 to an adult film actress named Stormy Daniels just a couple of weeks before the 2016 election to silence her and to make sure the public did not learn of the sexual encounter with the defendant. Cohen made that payment at the defendant’s direction, and he did it to influence the presidential election[4].

[1] This is the “Catch and Kill” scheme, which Merchan threw out as an object offense. So no wonder the case feels befogged and surreal, given that the Merchan threw out what Colangelo said the case was “about.” And if the case isn’t “about” the Catch and Kill scheme, what is it about?

[2] Presumably not with business records falsified in 2017, so how did the corruption take place?

[3] How is this not how any candidate would handle oppo? How is more conspiratorial than, say, using a lawyerly cut-out to put the Steele dossier in play, leveraging the dossier to get a FISA warrant, and then infesting one’s opponent’s campaign with spooks?

[4] Yes, it’s called campaigning. If Trump had gotten 51 intelligence officers to say Stormy Daniels was full of it, would that be OK?

Molineux Rule

Here is an explanation of the Molineux Rule, and how a judge’s violation of that rule led overturing Harvey Weinstein’s conviction. From Robert Weisberg at Stanford Law:

The charges in the New York trial were for crimes against three complainants. Weinstein was convicted for raping one of them and sexually assaulting another. The trial judge permitted the DA to introduce several other witnesses who testified to alleged sexual assaults by Weinstein, but those allegations were not part of the criminal charges in the trial. Under New York state’s century old “Molineux rule,” there are severe restrictions on the admissibility of so-called prior bad acts that are not part of the current charges. The concern is that the jury will infer that the defendant has a so-called propensity to commit acts of this sort, thereby distorting their judgment on his guilt about the formally charged crimes. The New York law has a few exceptions, such as where the prior acts are very distinctly relevant to a contested issue about the defendant’s intent, or to show a very distinctive pattern to his behavior. Here, the majority concluded that the trial judge crossed the line and thereby denied Weinstein a fair trial. Also, because the judge admonished Weinstein that if he testified on his own behalf, he would be subject to cross examination on these uncharged acts, the court ruled that Weinstein was unfairly deterred from exercising his right to testify.

Judge Merchan allowed Daniels to present some pretty lurid testimony. From Jonathan Turley (who is mostly pounding the table these days, but that’s an appropriate method here):

The prosecution fought with Trump’s defense counsel to not only call porn star Stormy Daniels to the stand, but to ask her for lurid details on her alleged tryst with Trump.

The only assurance that they would make to Judge Juan Merchan was that they would “not go into details of genitalia.”

For Merchan, who has largely ruled against Trump on such motions, that was enough.

He allowed the prosecutors to get into the details of the affair despite the immateriality of the evidence to any criminal theory.

Neither the [catch and kill] NDA nor the payment to Daniels is being contested. It is also uncontested that Trump wanted to pay to get the story (and other stories, including untrue allegations) from being published. The value of the testimony was entirely sensational and gratuitous, yet Merchan was fine with humiliating Trump… The most maddening moment for the defense came at the lunch break when Merchan stated, “I agree that it would have been better if some of these things had been left unsaid.” He then denied a motion for a mistrial based on the testimony and blamed the defense for not objecting more. That, of course, ignores the standing objection of the defense to Daniels even appearing, and specific objections to the broad scope allowed by the court. This is precisely what the defense said would happen when the prosecutors only agreed to avoid ‘genitalia.’ … Merchan said that he is considering a limiting instruction for the jury to ignore aspects of the testimony. But that is little comfort for the defendant. The court was told that this would happen, it happened, and now the court wants to ask the jury to pretend that it did not happen. Merchan knows that there is no way for the jury to unhear the testimony.

Merchand’s potential violation of The Molineux Rule could relevant on appeal for two reasons: First, the obvious potential to distort the judgment of the jury, as Weisberg says. More subtly, it could “unfairly deter” Trump “from exercising his right to testify.” Trump he really going to take the stand so Bragg can question him about all matters of his sex life short of genitalia?

Conclusion

I hope this serves as a reasonable summary of the state of play on the various elements of Bragg’s architecture (besides giving an account of the befogged and bewildering nature of the trial generally). Let’s close with a nasty twist of thought about the jury:

All it takes to block a conviction is one juror holding out. If members of the jury announce following deliberations that they can’t reach a unanimous verdict, the judge can give them an Allen charge, sending them back to essentially try again. But that would be a controversial move, as it is often viewed as a judge pressuring the holdout to join with the majority.

All that being said, this case would probably be a pretty quick conviction under normal circumstances. But imagine the incentives for a potential holdout: a book deal, traveling the country giving paid speeches to MAGA crowds, the prime-time interview on network television … and that’s just the beginning.

The consensus, across the board, does seem to be for quick conviction, working on the assumption that jurors do their civic duty. However, I think it’s very likely that Merchan has given grounds for appeal; Surtout, pas trop de zele, as Talleyrand once said.

NOTES

[1] Judge Merchan writes: “The ‘object offense’ referenced by Defendant as well as the terms ‘other crime” and ‘another crime’ carry equal meaning.” In my earlier post, I used “other crime,” but I think “object offense” is the more descriptive term, so I will use it going forward.

[2] Note that this diagram is different in detail from the earlier diagram from Asha Rangappa, presented here.

[3] McCarthy also makes the political point:

The campaign laws are so complex that the FEC’s role includes the promulgation of “regulations to implement and clarify these laws.” For its part, the Justice Department has produced an exacting enforcement manual of well over 200 pages, which has been edited numerous times, in order to walk federal prosecutors through the complex web of statutes and regulations.

Why does this matter? Well, if you weren’t born yesterday and you follow the news even casually, then you know that the Department of Justice is so territorial about its jurisdiction that it would make a tiger wilt in admiration. Similarly, the FEC jealously guards its turf. Do you really think for a moment that the Biden Justice Department and the FEC would sit in silent passivity if any other state prosecutor, besides Bragg in this particular case, usurped federal authority and undertook to enforce federal law — in a matter as to which the DOJ and FEC, after thoroughly investigating, had decided not to prosecute?

APPENDIX

I can’t even:

Here is my statement regarding the testimony of Stormy Daniels. Will DA Bragg pursue charges against her for falsification of business records, fraud, etc. pic.twitter.com/ELPNzfMsIC

— Michael Avenatti (@MichaelAvenatti) May 7, 2024