Imagine a future where, after a night of bar-hopping with friends, you can whip out your phone, consult a smartphone app connected to a wireless device stuck to the side of your arm, and find out exactly how hammered you are. It sounds like something you might see in the first couple minutes of a Black Mirror episode, but it could soon be reality—and be a huge help for people with certain challenging health conditions.

In a new study published Monday in the journal Nature Biomedical Engineering, researchers at the University of California San Diego have developed a device no bigger than a stack of six quarters that senses alcohol, glucose, and lactate. Aside from letting you know that you should get the Uber home from the bar rather than drive, the new wearable also has the potential to help those with diabetes have a more accurate picture of their blood sugar levels.

“This is like a complete lab on the skin,” Joseph Wang, a biomedical engineer at UC San Diego and study co-author, said in a press release. “It is capable of continuously measuring multiple biomarkers at the same time, allowing users to monitor their health and wellness as they perform their daily activities.”

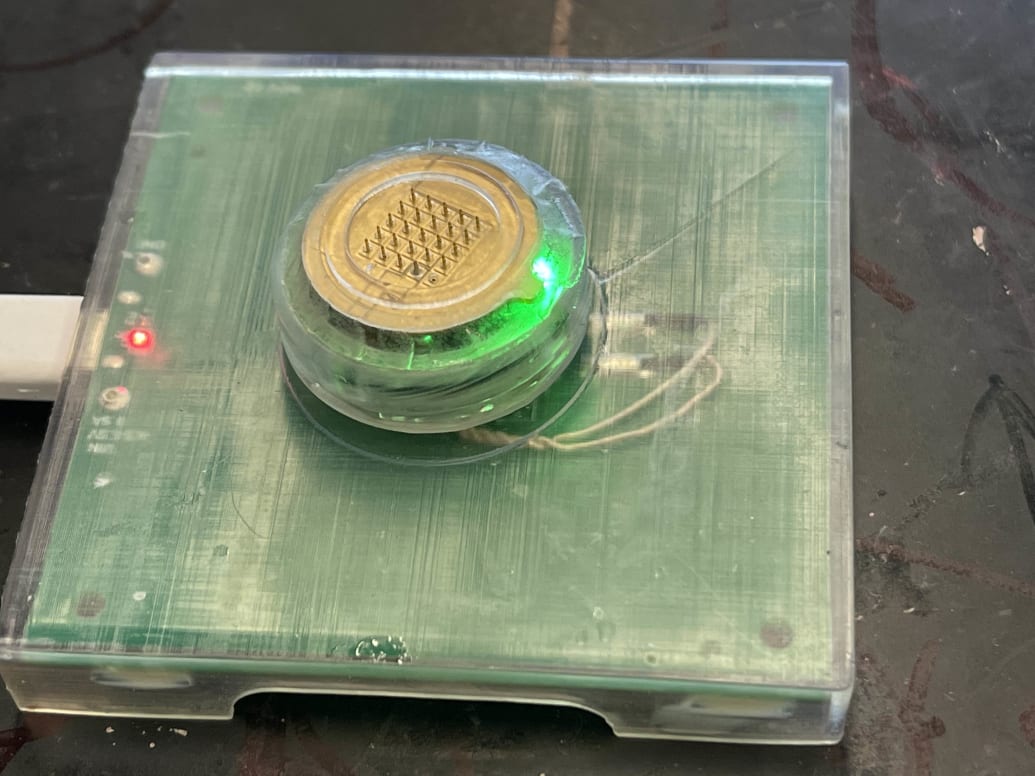

The disposable microneedle patch detaches from the reusable electronic case.

Laboratory for Nanobioelectronics/UC San Diego

Current wearable health sensors for people with diabetes are typically one-trick ponies. They can continuously monitor blood glucose levels—and do it very well—but little else. This information, while clinically useful, doesn’t provide a wide-lens view into the dynamic between blood sugar and elevated levels of alcohol (which can lower blood sugar) or lactate (which can indicate muscle fatigue and tissue damage). A device that can take these factors into account can allow someone with diabetes to more precisely manage their health by optimizing their physical activity or watching out for too many extra glasses of wine.

“With our wearable, people can see the interplay between their glucose spikes or dips with their diet, exercise, and drinking of alcoholic beverages. That could add to their quality of life as well,” Farshad Tehrani, a doctoral student at UC San Diego and co-first author of the study, said in the press release.

The device can be recharged on an off-the-shelf wireless charging pad.

Laboratory for Nanobioelectronics/UC San Diego

Another major downside to wearable health monitors is their reliance on invasive needle-based sensors. While their coin-sized device has needles, the UC San Diego researchers used disposable microneedles, which are painless and minimally invasive, measuring about one-fifth the width of a human hair. The needles also contain sensors that sample your body’s interstitial fluid once latched onto the skin. This fluid fills the spaces between cells and is chock full of biological chemicals like glucose, lactate, and alcohol once you’ve had a drink.

The magic happens when different enzymes inside the microneedles react with these chemicals, generating electrical signals. These signals are then analyzed by additional sensors inside the device before being wirelessly sent to a smartphone app the researchers developed. When the new wearable was tested out by five volunteers as they went about their day eating, drinking, and exercising, data about the chemicals collected were on par with those collected by conventional measuring methods, like a commercial blood glucose monitor or Breathalyzer.

“The beauty of this is that it is a fully integrated system that someone can wear without being tethered to benchtop equipment,” Patrick Mercier, an electrical engineer at UC San Diego and study co-author, in the press release.

If you’re in the market for this one-of-kind health sensor, you might have to wait a while for a commercially viable product. The device, while rechargeable, can only run for a few hours at a time currently. The UC San Diego team is also planning to run more extensive clinical trials that could test out the wearable’s potential to measure other health-specific chemicals, like antibiotic levels when treating bacterial infections.

But once fully fleshed out, the researchers see their health sensor as promising for a whole range of people beyond those with diabetes—from athletes who want to up their physical performance, to doctors monitoring their patients after an organ transplant, and to regular folks at home who love tracking their health stats. It’s like a Fitbit on steroids.