Fertility apps have always been sketchy. As I’ve experienced it, it’s a Faustian bargain of sorts: Take your chances on one of many options in your app store, and pick the one with the best reviews, or maybe the simplest interface. You’ll sign up feeling unsure of what to make of the opaque data policy, and then you’ll bear with the ensuing deluge of targeted ads – all in exchange for an accurate prediction of when you’re most likely to conceive. Judging by those ads for maternity clothes and organic cotton onesies, someone somewhere knows I’m either trying to conceive or have already given birth, even if they can’t decide which. I don’t like it, but I put up with it.

I’ve been mulling the subject of period and fertility trackers ever since I decided I was ready to become a parent, though for privacy’s sake, I didn’t imagine writing about it until after I’d given birth to said imaginary baby. But in the two months since Politico published a draft opinion in Dobbs v. Jackson, the case that has overturned the constitutional right to an abortion guaranteed by Roe v. Wade, a lot of people have been talking about period trackers. Some activists and privacy advocates have asked if the data captured by these apps can be used to help prosecute someone seeking an abortion in a state that doesn’t allow it. Some have simply exhorted readers to delete these apps altogether.

I understand why. And I also understand why people use these apps in the first place: Because the version of that app that’s built into your smartphone OS isn’t very good.

In my case, I have an iPhone. I’ve been using period tracking for a couple years now, though Apple began introducing these features much earlier, in 2015. From the beginning, Apple was criticized for moving slowly: Some observers wondered why Apple didn’t have women’s health features ready when it launched the Apple Health app the year before.

[embedded content]

In its current form, the app is decent in the sense that it can accurately predict when you’re about to menstruate, and it’s easy to log when you do, either through your iOS device or Apple Watch. This is useful not just for avoiding potential surprises, but for knowing when your last period started in case your gynecologist asks. (And they always ask.) What’s more, irregular periods can sometimes underscore larger health issues.

The fact that Apple hasn’t paid more attention to this, when hundreds of millions have downloaded third-party alternatives, is honestly surprising: Apple could own this space if it wanted to.

In order for it to do that, though, Cycle Tracking has to be equally good at helping people get pregnant or avoid pregnancy. Because ultimately, those users all need the same set of data, the same predictions, regardless of their intention. If you know you’re ovulating and want a baby, you should definitely have sex. If you’d like nothing less than to get pregnant, that ovulation window is also a useful thing to be aware of.

Here’s what Apple would need to add to its app to match its competitors and build a true all-in-one period and fertility tracker. (Apple declined to comment for this story.)

Ovulation prediction

Dana Wollman/Engadget

First off, it must be said that Apple doesn’t attempt to predict when you’re ovulating. What you’ll see is a six-day fertility window, shaded in blue. But not all fertile days are the same. One has a roughly 30 percent chance of conceiving on ovulation day or the day before; five days before, your chances are closer to 10 percent. Unless you plan to have sex for six days or avoid it that whole time, a six-day fertility window with no additional context is not very helpful.

Other fertility apps learn from previous cycles to predict how long your typical cycle is and when you’ll likely be ovulating. I’ve seen more than one app present conception odds on a bell graph, with some even displaying your estimated percentage of success for a given day. Apple can decide for itself how complex of an interface it wants, but it most definitely has the machine learning know-how to predict ovulation based on previous cycles.

A proper calendar view

Apple’s is the only period tracking app I’ve seen that doesn’t offer a gridded calendar view. Which is incredible when you remember everything related to fertility (and later pregnancy) is measured in weeks. Instead, Apple Health shows the days in a single, horizontally scrollable line. On my iPhone 12’s 6.1-inch screen, that’s enough space to see seven days in full view. Also, if you input any data, whether it’s sexual activity or physical symptoms, that day will be marked with a purple dot. That isn’t helpful at a glance when that dot could mean anything. Another tip for Apple: color-coding might help.

If I were just logging my period, I’d appreciate not having the red-colored possible period days sneak up on me. (Okay, okay, you can set notifications too.) But for those trying to conceive, a calendar view would help for other reasons, like matching factors like sexual activity and body temperature against your predicted fertile days. Which brings me to my next point…

An easier way to log and understand basal body temperature

Dana Wollman/Engadget

One way that many people measure their fertility is by taking their temperature every day, at about the same time. The idea is that your temperature shoots up right before ovulation, and drops back down after, unless you’ve conceived. It doesn’t matter so much what each day’s reading is; what matters is the pattern that all of those inputs point to. And the only way to see a pattern is to view your temperature readings on a graph.

This is how temperature tracking was meant to be done in the old days, before smartphones: with graph paper. It’s awfully difficult to spot the surge when you’re scrolling, one day at a time, through Apple Health’s left-to-right calendar. It is very easy to spot the surge when it’s presented as an infographic. And I know Apple could do a good job of this. This is already how Apple presents changes in my daily exercise minutes or fluctuations in my heart rate throughout the day.

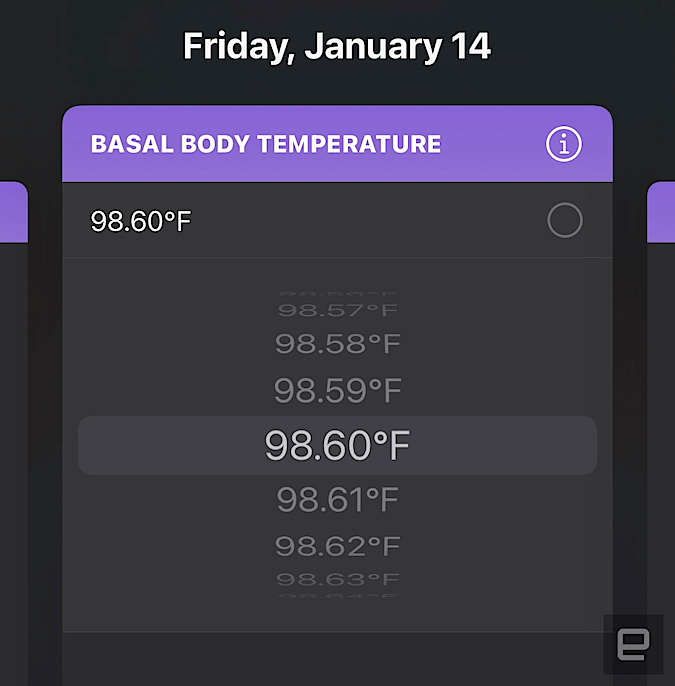

Oh, and while I’m ranting on this topic, Apple doesn’t just let you type in whatever number you see on your thermometer. You have to select it from a scrolling dial, similar to how you would set an alarm in the Clock app. (When you go to enter your temperature, you start at the last temperature you entered.) Basal thermometers show your reading down to the hundredth of a degree, so even mild fluctuations in temperature from one day to the next can lead to an annoying amount of scrolling.

The ability to recognize ovulation strips

Dana Wollman/Engadget

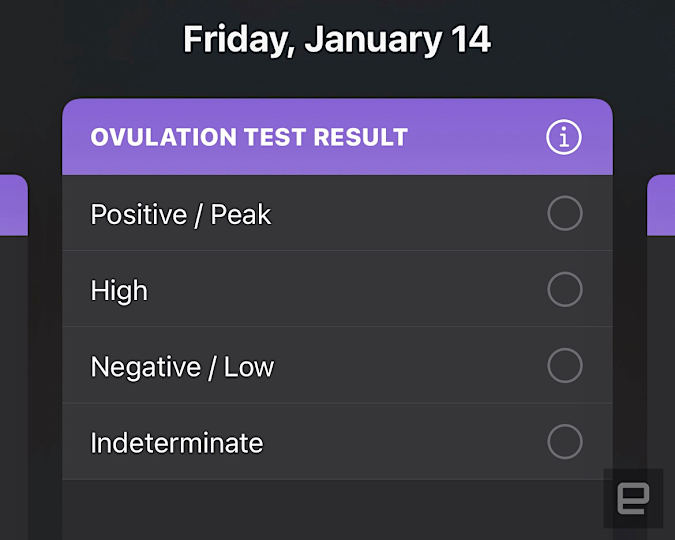

Not everyone uses temperature readings to predict ovulation. Many people use the newer invention of ovulation tests: at-home pee strips that measure Luteinizing Hormone (LH), which surges ahead of ovulation. The result always includes two lines, and how close you are to ovulating depends on how dark each of the lines are. Because that color exists on a spectrum, from light purple to very dark, it can be difficult to suss out the nuances with the naked eye, especially toward the deeper end of the color grade. Fortunately, many apps allow you to take or upload a photo of the results, and the app will use camera recognition to classify your test results into one of three categories: low, high or peak. Again, I have no doubt that Apple has the technology to do this.

Resources for pregnant people

One of the reasons people download and continue to use fertility apps after they get pregnant is that they can learn, week by week, whether their baby is the size of a raspberry, prune or avocado. These apps can also be a resource for first-timers who are feeling overwhelmed and unsure of what symptoms and bodily changes they can expect at each stage. The information in these apps vary in depth, and likely accuracy. There’s no governing body so far as I can tell that regulates what information apps include as resources. Not even the App Store. I’m not suggesting Apple write its own content. But it can use the same system of curation that it uses for the App Store, Apple News, etc. to provide users information from trusted outside sources, whether that be medical sites like WebMD or reputable medical centers like the Mayo Clinic.

All products recommended by Engadget are selected by our editorial team, independent of our parent company. Some of our stories include affiliate links. If you buy something through one of these links, we may earn an affiliate commission.