South Korean car manufacturer Hyundai just became the first company to use the rail corridor, which is being touted as a possible plan B to the embattled canal.

Just a few weeks ago, the Trump Administration was celebrating what seemed to be an early strategic victory over China in the US’ direct neighbourhood. As readers may recall, a consortium led by the investment fund manager BlackRock had just announced its purchase of 80 percent of Hong Kong-based CK Hutchison’s port holdings, giving the consortium control over dozens of ports in more than 20 countries, including, crucially, the Balboa and Cristobal docks at either end of the Panama Canal.

The sale of CK Hutchison’s ports business put “the ports [in Panama] under American control after President Donald Trump [had] alleged Chinese interference with the operations of the critical shipping lane,” noted an Associated Press article.

The message was clear: the Trump Administration is not going to stand by and watch as China expands its influence in the US’s own “backyard”, especially over strategic assets like the Panama Canal. To put this in broader context, the attempted buy out of the Panamanian ports came just three months after the opening of the Chinese-financed and -managed deep sea port in Chancay, which as Asia Times reported, signalled “the start of a new era of efficient, high-capacity shipping between China and Peru, with a connection to Brazil across the Andes.”

As a measure of Chancay’s importance to the Chinese Communist Party, Xi Jinping even travelled to Peru to inaugurate the mega port (as well as attend the 31st APEC Economic Leaders’ Meeting held in Lima), where he said:

“We are witnessing not only the solid and successful joint implementation of the Belt and Road Initiative in Peru, but also the birth of a new land-maritime corridor between Asia and Latin America and the Caribbean in a new era.”

Of course, this caused all sort of teeth gnashing in Washington, especially given that Chancay is more advanced than any seaport in the US. Within weeks, US officials were signing a strategic agreement with Ecuador’s Daniel Noboa government that allows the US to install military personnel, weapons and other equipment on the Galapagos islands, a UNESCO Natural Heritage Site in a country whose constitution expressly prohibits the establishment of foreign military bases. The island chain is 1,900 kms from Chancay.

Since its inauguration, Trump 2.0 has upped the stakes, showing a clear willingness every conceivable tactic, including gangster extortion, to reverse Chinese influence on the American continent, particularly in Mexico and Central America. As Conor recently reported, the Trump administration’s obsession with shipping lanes and maritime infrastructure extends far beyond the American continent:

Most indications are that the goal is to push back Chinese influence while cementing US naval dominance so as to be capable of enacting a global maritime blockade of China.

“Selling Out” the Chinese People

Against this complex backdrop, the BlackRock-led consortium’s purchase of CK Hutchison’s port holdings (outside of China and Hong Kong) was set to be consummated with a formal signing of the Panama ports transaction by April 2 — that is, tomorrow. But that, alas, will not be happening, at least not any time soon, since Beijing has decided that it, too, can play dirty on the global chessboard.

Last week, China’s State Administration for Market Regulation said it plans to “review [the sale] in accordance with the law to protect fair competition in the market and safeguard the public interest”. As the FT reports, the move came on the back of earlier commentary in the Ta Kung Pao, a pro-Beijing newspaper in Hong Kong, that called the sale a “spineless, grovelling” move that “sells out all Chinese people”.

The agreement “in principle” was announced in early March, with a formal signing of the Panama ports transaction expected by April 2. However, this is now set to be delayed, according to two people familiar with the matter.

Yesterday, the newspaper featured comments from Hong Kong politicians and Chinese lawyers urging the CK Hutchison to rethink the sale of its ports division, which is kind of ironic given that the main point of the sale was to “de-risk” its port holdings. Now, it is caught in the middle of a bitch fight between the world’s two superpowers, for which it has already paid a heavy price. Since news of Beijing’s objections to the sale broke on March 13, the company’s shares have fallen 13%, retracing more than half of the 25% gain after the deal’s announcement.

One Ta Kung Pao editorial even suggested that the sale could contravene Hong Kong’s national security laws, known as Article 23. If, as the FT notes, the deal were ultimately blocked, it could have major repercussions not only for Beijing’s already troubled relations with Hong Kong’s business elite but also Hong Kong’s reputation as a global financial centre:

CK Hutchison, controlled by Hong Kong’s richest man Li Ka-shing and his family, has increasingly been caught between Beijing and Washington over the Panama ports since US President Donald Trump complained of Chinese influence over the canal and said the US would be “taking it back”.

It is unusual for a Chinese state agency to review a deal involving a Hong Kong-based company. CK Hutchison’s holding company is incorporated in the Cayman Islands and the conglomerate’s ports in China are excluded from the sale.

“Is this a warning shot to others or a look to scuttle this deal?” one person familiar with the deal said.

“On paper, the SAMR reviewing how this deal affects the Chinese shipping industry under its anti-monopoly mandate makes a lot of sense. But does anyone really believe that or is this . . . the Chinese scuttling a deal which will then have ramifications on Hong Kong as a financial centre?”

“Torpedoing the deal . . . would send shockwaves all around the financial world,” said Josh Lipsky, senior director at the Atlantic Council’s GeoEconomics Center and a former adviser at the IMF. “The risks are so high for all involved.”

The End of the Belt-and-Road in Panama

The deal represented a triumph for the Trump Administration’s geostrategic aspirations in its own neighbourhood as well as a blow to China’s belt-and-road project, given that some 6% of global trade passes through the canal. According to the US International Trade Commission, the Canal “has 46% of the total market share of containers moving from Northeast Asia to the East Coast of the United States.”

Panama itself was the first country in Latin America to join China’s Belt-and-Road initiative, in 2017. However, the Panamanian President José Raúl Mulino, under pressure from US Sec of State Marco Rubio, recently said he would withdraw Panama’s Belt-and-Road membership when it comes up for review.

The CK Hutchison deal was also supposed to mark a major milestone for BlackRock’s global infrastructure ambitions. According to Bloomberg, Fink had personally called Trump and asked him to help BlackRock purchase the Panama Canal ports. The billionaire CEO reportedly boasted of BlackRock’s deep links with governments worldwide, stating, “We are increasingly the first call”. But apparently not in Beijing.

For Trump, the deal was all about “reclaiming” the canal for the United States — a message that, perhaps unsurprisingly, has not gone down well in Panama. This is a country wearily accustomed to US military interventions, the last of which took place in 1989 with George H W Bush’s invasion and toppling of Manuel Antonio Noriega, Panama’s strong arm dictator (1983-9) and former CIA asset and go-between during the US’ dirty wars in Central America. Much like Saddam Hussein a few years later, Noriega thought he could go his own way.

Trump has repeatedly denounced that US ships pay exorbitant prices to transit the waterway, though they, in fact, pay the same rates as ships of any other flag. But the deal is now on ice anyway, meaning that other options, including military ones, are back on the table.

US-Style “Partnering” With Panama

Even before Chinese regulators put the stick in the spokes, the Trump Administration had already directed the US military to draw up plans to increase the American troop presence in Panama, according to information leaked to NBC. As the NBC article notes, the amount of military force used will depend on the extent to which Panama is willing to, ahem, “partner” with the US:

U.S. Southern Command is developing potential plans from partnering more closely with Panamanian security forces to the less likely option of U.S. troops’ seizing the Panama Canal by force, the officials said. Whether military force is used, the officials added, depends on how much Panamanian security forces agree to partner with the United States.

The Trump administration’s goal is to increase the U.S. military presence in Panama to diminish China’s influence there, particularly access to the canal, the officials said.

Trump seems to believe that the US has, at the very least, joint, if not full, ownership rights over the canal due to the fact that the US government and banks financed its construction between 1904 and 1914. What happened just before 1904 is often forgotten or overlooked, however. The veteran US journalist Ken Silverstein jogged a few memories in his 2014 article for Vice, :

“In 1903, the administration of Theodore Roosevelt created the country after bullying Colombia into handing over what was then the province of Panama. Roosevelt acted at the behest of various banking groups, among them JP Morgan & Co, which was appointed as the country’s ‘fiscal agent’ in charge of managing $10m in aid that the US had rushed down to the new nation.”

US interests were myriad: on the one hand, Washington wanted access to, and control over, the canal that French builders had begun but failed to finish in the 1880s. At the same time, Wall Street banks were keen to create a new nation that would primarily serve their interests. As John Pilger reported for The Guardian in 2016, it was JP Morgan that would lead the American banks in gradually transforming Panama into “a financial centre – and a haven for tax evasion and money laundering – as well as a passage for shipping.”

Washington maintained control of the interoceanic waterway until 1977 during which time when then-US President Jimmy Carter signed with the then Panamanian leader, Omar Torrijos, the cession of US control of the facility 22 years later. The agreement came after years of protests in Panama against US occupation but was widely criticised by US conservatives at the time and is seen by Trump as a “serious mistake.”

But the Panama Canal has lost some of its lustre since the jungle country suffered an unprecedented drought in 2023. As we noted a few weeks ago, the BlackRock-led consortium’s participation in the canal could prove to be more of a curse than a blessing, especially given Panama’s ongoing water crisis. The canal already experienced a 29% drop in ship transits during fiscal year 2024 due to severe drought conditions, according to the Panama Canal Authority (ACP).

As Tom Neuburger wrote in a Jan 2024 article we cross-posted here, the plans to “fix” the Canal sound like plans to “fix” the climate: Bill Gates-style high tech fantasies.

[Bloomberg] “In the long term, the primary solution to chronic water shortages will be to dam up the Indio River and then drill a tunnel through a mountain to pipe fresh water 8 kilometers (5 miles) into Lake Gatún, the canal’s main reservoir.”

That’s a $2 billion project if it comes in on budget. But is it a long-term fix? Bloomberg admits that Panama “will need to dam even more rivers to guarantee water through the end of the century.” Sounds like Band-Aids to me. Lots of them. And residents of the to-be-flooded land are vigorously opposed, so it will be a political fight to move them.

“Another potential fix is decidedly more experimental … cloud seeding, the process of implanting large salt particles into clouds to boost the condensation that creates rain.”

The article is not optimistic that this will work. Another Gatesian dream: Pretty. Impossible. Or to say that differently, pretty impossible.

Plan B Option: Mexico?

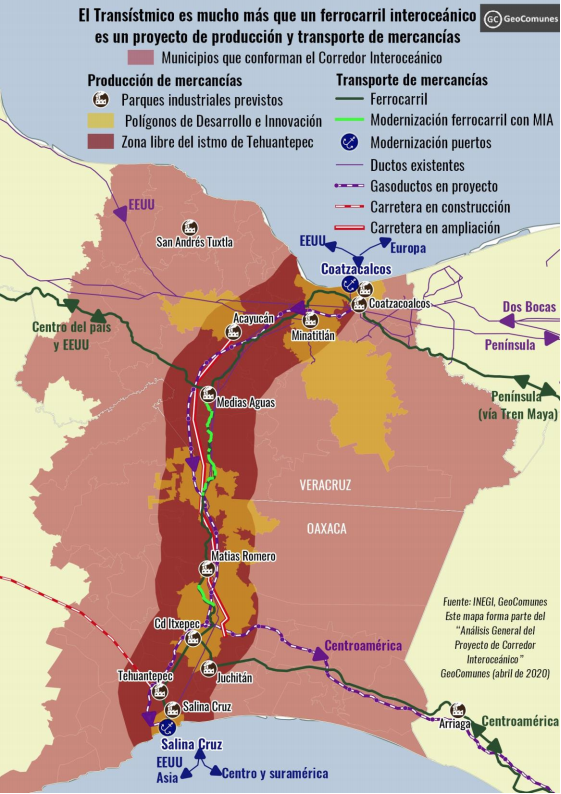

As the future of the Panama Canal hangs in the balance, Mexico has begun pilot testing the Interoceanic Rail Corridor of the Isthmus of Tehuantepec (also known by its Spanish initials, CIIT).

On Friday, a ship chartered by the Hyundai Motor Company docked at the Pacific port of Salina Cruz in Oaxaca. Its cargo, 600 Hyundai vehicles, were unloaded and placed on a freight train that then set off across the Isthmus, Mexico’s narrowest land bridge, to the port of Coatzacoalcos in Veracruz, where the cargo was loaded onto another boat destined for the US’ East Coast.

And just like that, the first genuine rival route, or perhaps better put, complementary route, to the Panama Canal was born. Or perhaps better put, reborn.

You see, most of the infrastructure for the project was built over a century ago. In fact, the 192-mile railroad joining the two main ports was opened in 1907, seven years before the inauguration of the Panama Canal, and within no time was plying as many as 60 trains a day carrying things like sugar from the Caribbean on their way to the US West Coast. But its success was short lived. When the Mexican Revolution broke out in 1910, the railroads were increasingly used to transport weapons and troops rather than freight. Four years later, the Panama Canal opened offering a more attractive route to international businesses.

Gradually, over time Mexico’s interoceanic railroad system fell into disrepair, and while many recent governments in Mexico have talked about rebooting the system, it wasn’t until Andrés Manuel López Obrador (aka AMLO) took power in 2018 that words actually turned into action. As we reported in September 2023, if completed and done well, it will probably represent the most important infrastructure project of Lopéz Obrador’s presidency.

The goal is not just to turn Mexico into a logistics powerhouse but also to spread wealth across the country by boosting economic opportunities in Mexico’s poorer, long-neglected southern states (Oaxaca, Veracruz, Tabasco, etc). This will largely be through the development of ten industrial parks, or so-called “free zones”, along the route. The project will also include the construction of four new highways, three airports, a gas pipeline and a fibre-optic network.

As the problems stack up in Panama, other interoceanic land routes are coming under consideration, including a rival canal in neighbouring Nicaragua, which almost got built instead of the Panama Canal at the turn of the 20th century, as well as interoceanic rail corridors in Honduras and Colombia. But for the moment Mexico’s CIIT has one clear advantage over all these other projects: it is close to completion, and that is largely thanks to all the work undertaken in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

“An Exceptional Project”

While the journey time of the CIIT (6-7 hours) is slightly shorter than the Panama Canal (8-10 hours), you also have to add in the time it takes to load and unload thousands of shipping containers off a ship onto a train and then back on to a ship at the other end. According to a video report by the Wall Street Journal in September last year, “Mexico still has a lot of work to do to get its ports ready for a large influx of cargo”.

This was a point that President Sheinbaum herself addressed in her Monday morning press conference:

“Several very important cranes are about to arrive. There will also be a storage facility for grains that is also important, and other actions to strengthen the port of Salina Cruz and that will allow freer movement. It is an exceptional project that provides an alternative to the Panama Canal, and when the port of Salina Cruz is complete, it will have much more activity.”

The total transit time for the Hyundai cargo was around 72 hours, according to local sources. Granted, this was the first pilot test but it still compares unfavourably with the Panama Canal — unless of course one takes into account the possible waiting times for ships before passage through the canal, which during periods of low rain can mean days or even weeks of hanging around off Panama’s coastline. During the 2023 drought, waiting times reached as long as 14 days, leaving some carriers little choice but to bid millions in extra fees to jump the line.

Another advantage of the CIIT for a shipment from, say, South Korea to New York is that you wouldn’t have to go all the way down to Panama, navigate the canal and then go all the way back up again. Also, the long-term goal of Mexico’s interoceanic rail corridor is to bring the journey time down to low double or even single-digit figures as the logistics systems at the two ports gain in efficiency. According to the WSJ report, it should ultimately take around 15 hours for cargos to pass through Mexico.

But as Mexican journalist Agustín García Villa notes, the success of a project of this scale and grandeur will require many things, including a trained workforce, technology, super-rapid processing of containers at the ports (which is good for all businesses, including, of course, drug trafficking ones), reliable energy sources, and the development of properly urbanised mid-sized cities that guarantee an adequate supply of housing, schools, hospitals, health centres, energy and markets. It will also depend on the amount of security Mexico’s marines can provide to the strategic infrastructure.

All of that, in turn, will require a steady flow of significant investment as well as long-term political commitment. The former is, for the moment, amply covered, with money coming in from all sides, including up to $2.8 billion from the Inter-American Investment Bank. Put simply, big business, not just from the US, wants this project to happen. So, too, does the Claudia Sheinbaum government, which took over the reins of power from AMLO last October.

Ultimately, as the WSJ report concludes, Mexico’s re-emerging interoceanic rail corridor is unlikely to rival Panama Canal in terms of capacity or speed of transit even once complete. But it could serve as a very useful complement. As Doctor Yasmine Sabri, associate professor of logistics at University College London, tells the WSJ, rather than competing with each other, perhaps the two could work together by sharing data, enabling them to reroute vessels whenever there is a chokepoint, whether it is in Panama or Mexico.

However, big questions still remain. For instance, how much opposition will the construction of industrial parks in Oaxaca and Veracruz face from local indigenous communities? If there is strong resistance, how will the Sheinbaum government respond? Like AMLO before her, Sheinbaum prides herself on representing indigenous rights and voices.

It also remains to be seen how the Trump administration will respond to the CIIT project as and when it gradually comes on line. Of course, Trump will have somewhat more difficulty bullying Mexico into submission than it did Panama, but it can still pull some pretty large levers, including, of course, tariffs and the threat of military intervention.

Will Chinese companies be interested in investing in the industrial parks along the route, as it has done in so many other infrastructure projects in southern Mexico?

Much will depend on whether Mexico continues to serve as a point of entry for competitively priced manufactured goods into the US market, which cannot be taken for granted. Of course, Washington will try to talk Mexico out of accepting any offers of Chinese funds.

Mexico, like Panama, finds itself caught in a tussle between two apex superpowers, and is already paying a heavy price. US pressure to impose equivalent tariffs on Chinese goods continues to rise. To assuage US demands, the Mexican Iron and Steel Industry Chamber has even called for the Sheinbaum government to withdraw from the Trans-Pacific Partnership in order to prevent Chinese steel imports from entering Mexico via TPP signatory nations such as Malaysia and Vietnam.

If the Trump administration does try to impose its will on Mexico’s re-emerging trade route as it has tried to do with the Panama Canal, so far unsuccessfully, it will heap even further pressure on the rapidly fracturing global trade system. And if this goes on for long enough, global trade volumes will ultimately begin to fall, perhaps even obviating the need for so many transoceanic trade routes in the first place.