“An industrial economy’s decline usually provides a grab bag of opportunities for financial predators and vulture funds.”

– Michael Hudson, “The Destiny of Civilization”

And so it goes in Germany where the decimation of the country’s industry and its working class continues apace. Volkswagen added to the carnage on Monday with plans to close three factories and potentially lay off tens of thousands of workers.

How are the “financial predators and vultures” doing? Quite well. Here are some numbers from WSWS:

While poverty is growing, at the top end of the scale the number of super-rich is on the rise. The annual ranking by Manager Magazin shows that the number of billionaires in Germany has recently risen by 23 to 249.

Manager Magazin has published a list of the 500 richest Germans and calculated that their private assets and wealth in 2023 amounted to a record €1.1 trillion, an increase of €53 billion compared to the previous year. This sum, €1.1 trillion, is almost two-and-a-half times the federal budget for the same year…about 0.6 percent of the population, own 45 percent of the country’s total wealth.

And Germany continues to become a much more unequal society with a Bundesbank survey finding that the top 10% of households have at least €725,000 ($793,000) of net assets and control more than half of the country’s wealth, while the bottom 40% of households have at most €44,000 of net assets.

What’s causing the surge in inequality and how have the wealthiest found ways to keep growing their fortunes while the national economy breaks down? Let’s take a look at the main drivers of inequality and then compare them to situation in Germany today.

Here’s Dutch economist Servaas Storm in a paper featured here at NC back in 2021 explaining the primary causes of increasing economic disparity:

The key driver of rising income inequality is the stagnation of real wage growth for the bottom 80% or so of U.S. households (Taylor and Ömer 2020). Real wage growth was suppressed below labour productivity growth, and this led to a secular decline in the share of wages (and a rise of profits) in national income. The main cause of the wage growth suppression has been the abandonment of full employment as the primary target of macro policy-making, in favour of inflation control, at the end of the 1970s. Fiscal policy was deprioritized in favor of monetary policy, conducted by independent central banks, single-mindedly focused on building credible reputations as inflation hawks, and counter-cyclical fiscal stabilization was made anathema by subjecting fiscal policy-making to rigid and deflationary rules, irrespective of the business cycle. For a period of time after the global financial crisis of 2008, austerity zealots, dreaming of expansionary fiscal consolidations, intensified the fiscal repression, bringing about one of the slowest and most costly economic recoveries from a crisis in history.

Labour markets were enthusiastically deregulated, with the explicit and generous approval of central banks and governments, to break the structural inflationary power of unions and to create a flexible reserve of surplus workers with no choice but to work in temporary low-wage jobs in what is now known as the ‘gig’ economy. Globalization and offshoring contributed to breaking the countervailing power of organized workers because they offered corporations (the threat of) an opt-out possibility that was not available to workers. Taken together, the change in macroeconomic policy regime produced a structurally low-inflation economy, based on ‘traumatised workers’ in precarious jobs, who could not plausibly fight for higher wages and more secure employment conditions, given their daily struggles and the systemic biases they are facing. The wellspring of cost-push inflation had been radically removed.

Stagnant wages and incomes for the 90% mean that income (and wealth) inequality rises and that aggregate household savings go up (as shown by Mian, Straub and Sufi). Higher household savings reduce consumption demand, which holds up fixed business investment for the domestic market. In effect, aggregate demand growth stagnates, and pressures for demand-pull inflation evaporate. With inflation (and expected inflation) being low in structural terms, central banks lower the interest rate, in accordance with the recommendations based on the monetary policy rules proposed by establishment economics.

The low interest rates, in turn, fuel asset-price bubbles, creating wealth gains for the rich, and over-indebtedness for the bottom 90% of households, which use cheap credit to finance essential expenses on education, medical care and housing. This reinforces wealth and income inequalities, and pushes up asset prices even more, but this does not lead to higher economic growth and better jobs, because the richest 10% use their savings and wealth gains not for investments in the real economy, but to speculate in financial markets. The past two decades have made it abundantly clear that the gains made by the top 10% in financial markets do not trickle down to the real economy.

Now let’s take some of Storm’s key points and see how they’ve been applied in Germany. In many ways the crises of the past four years — first the pandemic and then the self-inflicted wound of the country’s Russia policy — have put long-term trends into overdrive:

Stagnation of Real Wage Growth. “German wages set to rise at the fastest pace in more than a decade” announced a recent headline at Euronews. Sounds great, but if we dig in a little ways we get to this:

“The price-adjusted level of collective wages is still well below the peak value of 2020”, although about half of the purchasing power losses of previous years have been compensated for.

Ouch.

Breaking Labor. That’s been going on for years. German Trade Union Confederation (DGB) membership overall has dropped from 9.3 million in the mid-1990s to 5.6 million now as older workers retire and union leadership has prioritized identity politics over class struggle in recent years. DGB acts more as a wage-cut negotiator. As DW notes, during the pandemic and Ukraine crises, the unions “have been instrumental in ensuring that there has been no mass unemployment during this period, by working with the government and employers to adjust to short-time contracts and negotiating compensation packages.”

In a neat twist, among the ten wealthiest Germans are heirs to Nazi-era wealth (e.g., Porsche and Klatten/Quandt) who are major shareholders of the same corporations that are currently enforcing mass layoffs, wage cuts and plant relocations.

Create a Flexible Reserve of Surplus Workers. Germany is currently home to more than one million “temporary” Ukrainian refugees. That temporary label means ambiguity and fear of repatriation. It also can make for more pliant workers for capital. Millions of other refugees and migrants have arrived in Germany in recent years as Berlin promoted “a more open-minded approach with a view to attracting labor.”

Germany, like every other neoliberal society, has for decades pursued a strategy of more flexible employment, which means more part-time, marginal and temporary employment. The country has experienced the strongest growth of in-work poverty in the EU with close to 10% of workers at risk (as of 2017).

Offshoring. German companies are increasingly outsourcing industrial production as a fix to Berlin’s self-imposed decline in competitiveness due to loss of Russian pipeline gas.

Stocks. The German stock market is up 15 percent since the beginning of the year despite the country being the worst performing major developed economy. The top five percent own 41.6 percent of total assets (real estate, securities, other financial assets), but ‘only’ 15.8 percent of income.

Let’s take a deeper look at one of those assets: real estate.

Housing Crisis

Germany is a country of renters and is by far the leader in Europe in rentership with more than half of the population not owning their own home. It was long argued that Germans don’t need a lot of money because of high-quality public services and low rents. Well, that’s all changed.

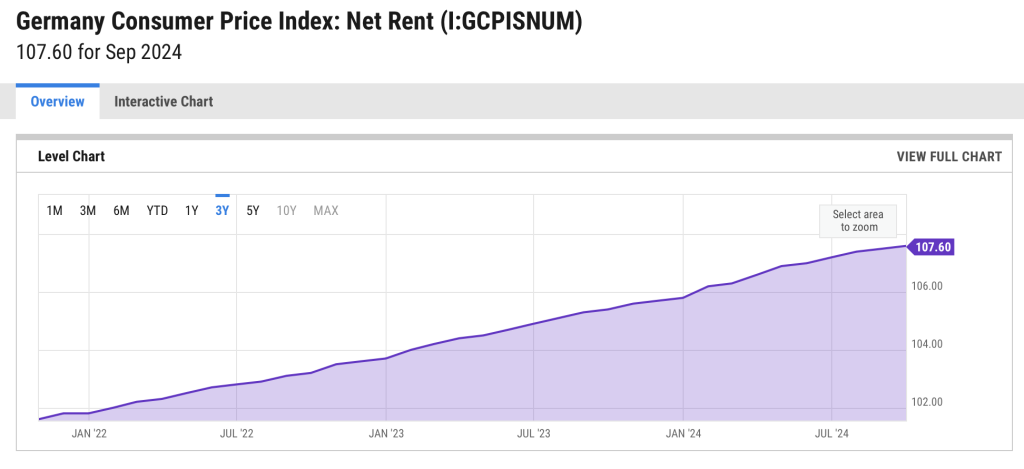

Rents continue to climb as real wages decline:

Who owns most of German real estate if the majority of people don’t own their own homes? It’s difficult to know for sure:

While every person in Germany who applies for the welfare payments known as Hartz IV must disclose the full extent of their wealth and possessions, data on large-scale property owners is nebulous at best. Although Germany’s Federal Office of Statistics has meticulously recorded how many homes were built since the end of World War II, clarity on who owns what and their current worth is elusive.

While precise data might be scarce, we can pick up trends that are similar to other neoliberal economies. Here’s DW:

But Germany is now paying dearly for its previous political mistakes: the federal government sold thousands of apartments to private investors, while at the same time local governments drastically reduced the construction of social housing.

Oops. More and more foreign investors are also reportedly investing in real estate in Germany, which is the largest real estate investment market on the European continent. The German government is desperately trying to appear to combat the skyrocketing rents and has now extended the rent freeze until 2029. This means that when a new lease is signed, the rent cannot be more than ten percent higher than a comparable lease in that area. However, there are exceptions for new buildings, extensively modernized, or partially furnished apartments.

Those loopholes help ensure that rents continue to rise despite the freeze being first enacted in 2015. Here’s more on the joke of the rent freeze from The Week in Housing:

…landlords frequently do not comply with the rent brake regulations, employing various tactics to evade compliance (much like the Irish case). Many landlords advertise rental properties at prices that exceed the rent brake’s maximum allowable rates, while others attempt to bypass the regulations entirely by offering ‘furnished’ rentals or carrying out renovation activities, which exempt their properties from the price caps. Moreover, there is a lack of uniform enforcement mechanisms or central oversight to ensure landlord compliance with the regulations and impose sanctions for non-compliance. Consequently, the burden of enforcing the rent brake regulations falls t most often on tenants, who may lack the knowledge, resources, or security to do so effectively. Many tenants are still unaware or unsure of the exact regulations in place and therefore unable to make use of the regulations. Additionally, tenants, who are desperate for accommodation, are often reluctant to fully use all of their legal options out of fear of the impact on their relationship with their landlord, on whom they are dependent.

There are also fundamental flaws of the rent calculation system. The functionality of the rent brake is intricately tied to the local reference rents, the representative cross-section of rents typically paid for comparable housing in the area. But the data usually fails to accurately reflect prices. That’s because one measure comes from stakeholders’ knowledge rather than data, and the other measure is based on faulty data with a lack of transparency in its criteria.

With loopholes galore, it’s no wonder that vultures like UBS Asset Management are licking their chops:

The German residential market has a traditionally strong rental market with more than 50% tenants1. Over the past two years, the tenant market has received a further boost due to increased mortgage costs and further decreasing affordability of owner-occupied property despite the fall in prices observed in 2023.

In addition, strong population growth, driven by net migration, has boosted demand. Over the past 10 years, the German population has grown by 3.5 million people to around 84.7 million at the end of 20232.

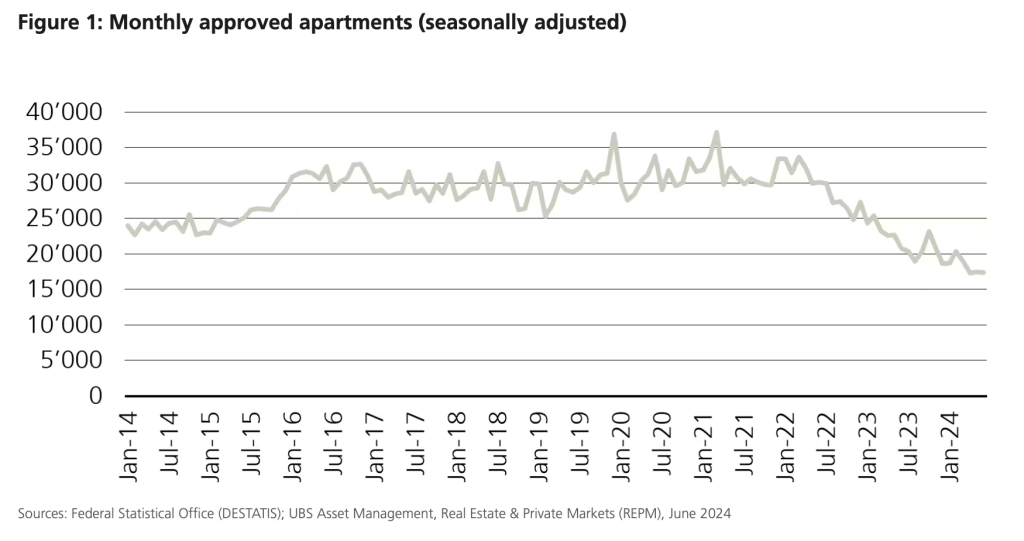

However, the increasing demand meets a declining expansion of supply. The government’s target of 400,000 new apartments per year has been undercut continuously with the number of yearly newly built residential units ranging somewhere between 220,000 and 275,000 over the past 10 years. Thus, the problem of insufficient construction activity has existed for some time. It has even become significantly worse in the wake of the increase in construction and financing costs over the last two and a half years. This shows in the number of building permits, which have dropped by 42% between June 2022 and June 2024.

The combination of rising demand and declining supply expansion results, unsurprisingly, in falling vacancies. Over the period 2012 to 2022, the average German apartment vacancy rate fell from 3.3% to 2.5%.4 The low vacancy rate is particularly pronounced in key cities, which recorded a vacancy rate of only 1% in 2022.

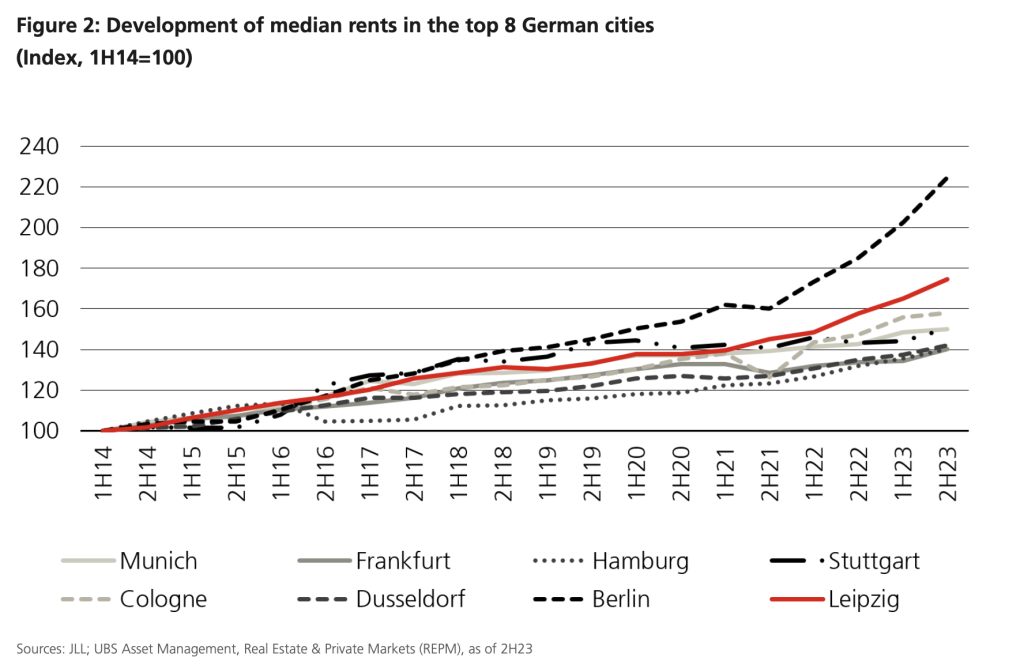

…Accordingly, the shortage in the rental housing market is reflected in significant rental growth. From 2014 to 2023, median rents in Germany’s eight major population centers rose by around 60%, according to JLL. Berlin stands out with particularly strong growth with its median rents doubling. Over the same time frame, the population in Berlin also grew by 9%, significantly more than in Germany as a whole (4.3%).

According to the projections of the Federal Statistical Office, the population in Germany is expected to grow by 0.7% from 2022 to 2040. The number of households is, however, expected to grow more strongly due to the continued trend towards a smaller household size. This will then continue to increase the demand for housing. Furthermore, due to ongoing urbanization, household growth should be stronger in cities and their agglomerations.

In view of the projected increases in demand, while construction activity is expected to remain subdued, one can hardly expect rental growth to calm down significantly. PMA expects average rental growth of around 3.1% p.a. in the 15 largest German cities and 3.4% p.a. in the top eight between 2024 and 2028 (see Figure 3). Again, Berlin is expected to outpace the rest of the country with an expected rental growth of 4.4% p.a., followed by Stuttgart at 3.9% p.a. With a forecasted inflation rate of 1.7% p.a. over the same time frame, the segment’s inflation protection should, however, be more than a given in the next years across all of the 15 largest cities.

As discussed in our previous piece, the corrections that have taken place in the course of the interest rate turnaround are helping investors to find attractive entry opportunities. Although capital growth cannot be expected to return to levels as during the negative interest rate era, growing cashflows can still be expected to increase for real estate investors in the near future.

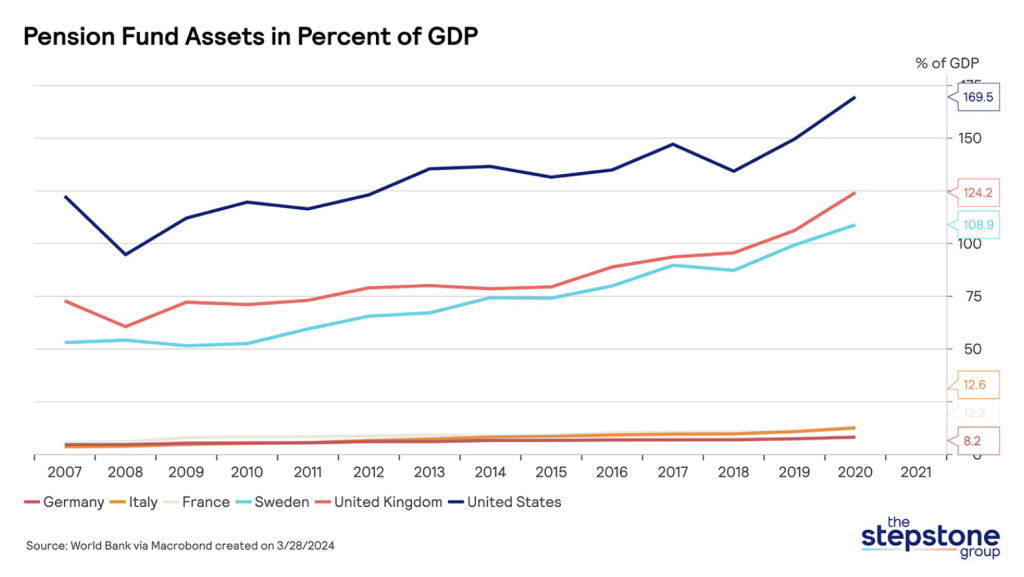

Privatize the Pension System

As the economy flounders and the workforce gets hammered, the vultures are sounding the alarm over the funding of the state pension system. Here’s Deutsche Welle:

A considerable chunk of the federal budget goes into propping up the pension system: €127 billion ($138 billion) will flow into the retirement fund in 2024, a third of all government spending. This sum is estimated to almost double by 2050, which is bad news in times of high expenditure in other areas such as defense.

What’s the solution? Scale back defense spending? Rethink the whole war on Russia fiasco? No, it’s to start privatizing the pension system.

Finance Minister Christian Lindner of the neoliberal Free Democrats is pushing a plan for the federal government to take out a loan of 12 billion euros (increased by three percent annually) and invest it in the stock market.

Lindner’s plan hasn’t come to pass yet, but as the economic situation continues to deteriorate, the calls from financial “experts” for “reform” will no doubt grow louder.

Sahra Wagenknecht, a former Left Party politician who earlier this year founded her own populist party BSW, has been campaigning on pension security, which is helping her party find increasing success. Meanwhile, Lindner’s Free Democrats are currently sitting below the five percent threshold in polls that would see the party excluded from the next Bundestag.

As Lindner and the financial experts profess their concern for the funding for the pension system, it’s worth considering the other ways Germany caters to its superrich. Reform of these giveaways are not factored into their fixes for the pension system:

Stefan Bach, a public economics research associate at the German Institute for Economic Research (DIW), pointed out that the highest earners can often skirt income taxes. “The superrich, the giant incomes, the businesses — the Klatten, Quandt, and Oetker families and so on — the family businesses, they aren’t even included because their income is largely separated into business structures and therefore is not subject to the progressive income tax,” he told DW.

In contrast, the average German employee also has a heavy state benefit burden. According to a 2021 OECD report, single workers bear a higher net average tax burden in Germany than in any other OECD country — meaning a German employee pockets the lowest percentage of disposable pay.

…Bach pointed out how superrich business families can also advantageously bequeath wealth. “The superrich with giant yearly incomes, say 20 million and up, they don’t pay any inheritance tax if they have business wealth that passes along tax privileges,” he said. He calls the inheritance tax a “sandwich tax,” because it most heavily burdens those in the middle; the lower end doesn’t have much if anything to pass on and the very top can lower their tax burden.

Conclusion

Friedrich Merz, leader of Germany’s opposition Christian Democratic Union party and odds-on favorite to be the next chancellor, says he wants to send German Taurus missiles to Ukraine to be launched into Russia. It’s dangerous rhetoric, but we’ll see if Project Ukraine is still sputtering along by the time Merz potentially takes charge and can get his wish.

Yet Merz’s comments highlight an important point about the German political class’ endless bloviating about the Russia threat. Despite all the talk, they’re doing precious little on that front. Here’s a September report from the Kiel Institute:

Russian military industrial capacities have been rising strongly in the last two years, well beyond the levels of Russian material losses in Ukraine. Meanwhile, the build-up of German capacities is progressing slowly. We document Germany’s military procurement in a new Kiel Military Procurement Tracker and find that Germany did not meaningfully increase procurement in the one and a half years after February 2022, and only accelerated it in late 2023.

Given Germany’s massive disarmament in the last decades and the current procurement speed, we find that for some key weapon systems, Germany will not attain 2004 levels of armament for about 100 years. When taking into account arms commitments to Ukraine, some German capacities are even falling.

What the great Russian menace has done, however, is cause the German elite to kill Germany’s industrial economic model.

Remember Berlin’s grand plans to produce “green steel” following its turn off of Russian gas? The government to great fanfare earmarked billions to help Thyssenkrup build a plant at its Duisburg site. Well, turns out it doesn’t make any financial sense and the company wants to pull the plug.

The blame cannons for the fall of Germany are increasingly being set on China now in addition to Russia.

Ouch. There we go.

Volkswagen plans to shut at least three factories in Germany, lay off tens of thousands of staff and shrink its remaining plants in Germany.

Unlike some of their Chinese competitors, German carmakers also have to churn out profits. https://t.co/WHs4qR8Ote

— Sander Tordoir (@SanderTordoir) October 28, 2024

Meanwhile, the financial predators at home continue to break labor and financialize the country with more outsourcing, more wage suppression, more privatizations, and more social austerity. In other words, a buffet for the vultures.