Mr. Market falling out of bed due significantly to the Trump tariff whiplash has freed the business media to go with both barrels after Trump economic policies. Some headlines in the last two days:

Wall Street Fears Trump Will Wreck the Soft Landing Wall Street Journal

Is Trump Taking a ‘Liquidationist’ Approach to the Economy? Wall Street Journal

CEOs Don’t Plan to Openly Question Trump. Ask Again If the Market Crashes 20%. Wall Street Journal. Subhead: “Behind closed doors, business leaders air plenty of concerns about the administration and its policies.”

US CEOs Need to Find Their Missing Backbones Bloomberg

Trump’s $1.4 Trillion Tariff Threat Spurs Companies to Seek Cover Bloomberg

How Do You Sell America on a Recession? Bloomberg

U.S. markets tumble as Trump dismisses economic fears CNBC

Trump ‘an agent of chaos and confusion, economists warn CNBC — but a U.S. recession isn’t in the cards yet CNBC. Note the part after the dash does not appear in a search.

Musk’s cuts fail to stop US federal spending hitting new record Financial Times

Wall Street loses hope in a ‘Trump put’ for markets Financial Times

Trump’s tariffs are starting to bite American builders Business Insider

I’m a Canadian mom who frequently traveled to the States. Now I’m avoiding the US and boycotting American products. Business Insider

For the first time, a majority of Americans don’t like Trump’s economic policies Business Insider

And yes, not only is this selection not unrepresentative, but there is more where that came from.

Even libertarians are turning on Trump:

Nobody is pulling punches on Trump’s handling of the economy in the White House briefing room … not even Fox News. pic.twitter.com/jYN7ubMYxs

— The Recount (@therecount) March 11, 2025

The DOGE Tracker Shows DOGE Savings Only 8.2 Percent of the Claim Michael Shedlock

How Do We Lower the Trade Tensions Between the U.S. and Canada? Michael Shedlock

And even though the economy is softening (as we’ll see below, at a quickening pace due to consumers cutting back on spending), inflation pressures have yet to meaningfully abate:

Beneath the Skin of CPI Inflation: Pace Slows from Spike Last Month, but 6-Month CPI Accelerates Further, Worst Increase since September 2023 Wolf Richter

Price of Natural Gas Futures Up 140% Year-over-Year: One More Reason for Inflation to Not Back off Easily Wolf Richter

Inflation eased in February, but trade war threatens higher prices Washington Post

On the one hand, eggs are only eggs. On the other, they have come to symbolize the Biden and now Trump Administration’s inability to curb inflation:

The cost of eggs in the U.S. jumped 10.4% last month, the Consumer Price Index shows. Eggs are nearly 60% more expensive than a year ago. https://t.co/p9kcmzK384

— The Associated Press (@AP) March 12, 2025

Mind you, not all business/economic tsuris is Trump’s fault:

How things got so bad for airlines seemingly overnight Business Insider

We’ll briefly turn to two new stories on Trumponomics, which go beyond Mr. Market’s misery and tariff freakout. One is the lead item in the Wall Street Journal, Consumer Angst Is Striking All Income Levels. The story describes clearly how the rate of decline in confidence and spending accelerated in February as compared to January. And this is before Musk started threatening bulwarks of many Americans finances, Social Security and Medicare. Remember it isn’t just retirees who get whacked. Those within 10 to 15 years of retirement who expected Social Security to be a significant part of their retirement funding are likely to hunker down further on spending to try to bulk up their nest eggs. From a reader by e-mail:

I am slated to start getting my SS in September after waiting until the end of the window. The promised amount will be a substantial part of my retirement income. Ditto for my better half who will retire at the end of June. It better be there. I have paid into the system with every paycheck since I was 15 years old in the summer of 1971.

Those who made Bernie Sanders impossible, twice, made Donald Trump inevitable, twice.

The opener from from the Journal’s account:

American consumers have had a lot to fret about so far this year, between never-ending tariff headlines, stubborn inflation and most recently, fresh fears about a recession. These concerns seem to be hitting spending by both rich and poor, across necessities and luxuries, all at once.

Take low-income consumers: At an interview at the Economic Club of Chicago in late February, Walmart Chief Executive Doug McMillon said “budget-pressured” customers are showing stressed behaviors: They are buying smaller pack sizes at the end of the month because their “money runs out before the month is gone.” McDonald’s said in its most recent earnings call that the fast-food industry has had a “sluggish start” to the year, in part because of weak demand from low-income consumers. Across the U.S. fast-food industry, sales to low-income guests were down by a double-digit percentage in the fourth quarter compared with a year earlier, according to McDonald’s.

Things don’t look much better on the higher end. American consumers’ spending on the luxury market, which includes high-end department stores and online platforms, fell 9.3% in February from a year earlier, worse than the 5.9% decline in January, according to Citi’s analysis of its credit-card transactions data.

Costco whose membership-fee-paying customer base skews higher-income, said last week that demand has shifted toward lower-cost proteins such as ground beef and poultry. Its members are still spending but are being “very choiceful” about where they spend, Chief Financial Officer Gary Millerchip said. He said consumers could become even pickier if they see more inflation from tariffs.

The Journal helpfully provides charts that show that the big Biden deficits did not translate into fatter wages:

Later in the Journal’s discussion:

The economy has seen pockets of weakness in recent years, but nothing that suggests such widespread weakness…. Several years of inflation—particularly on necessities such as groceries, rents and utility bills—have hit poorer Americans hard. But a strong stock market, buoyed by artificial-intelligence hype, kept wealthier folks spending.

Recall how we have repeatedly featured analyses by Tom Ferguson and Servaas Storm that showed how depending groaf has become on the outlays of the richest cohort, to the degree that it was a big factor in stoking inflation. The Journal later took up this thesis.

But now:

This week alone, consumers have had plenty of new developments to digest. President Trump on Sunday declined to rule out a U.S. recession as a result of his economic policies, causing stocks to plummet. This was followed by yet another roller coaster of tariff threats, counter-tariffs and reversals. While Wednesday’s inflation data showed price increases slowing down slightly in February, that is cold comfort because it is too early to reflect the effects of Trump’s tariffs…

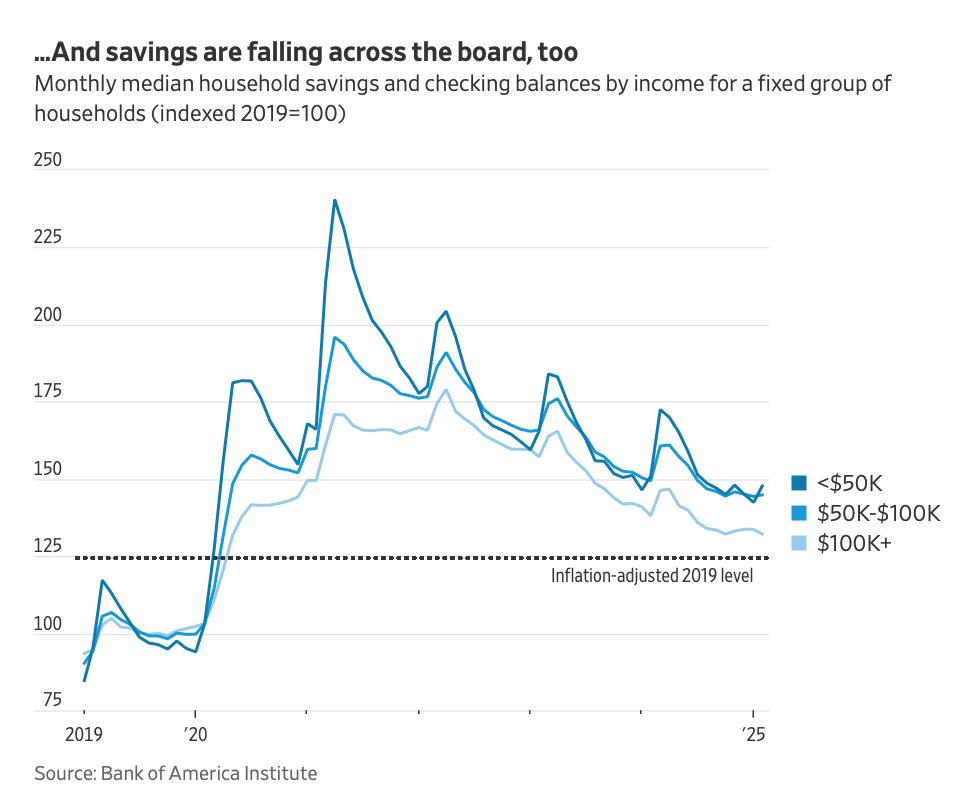

Many also have less cold hard cash on hand. Checking and savings deposit balances across all income levels have declined over the 12-month period through February and are getting closer to inflation-adjusted 2019 levels…

What this means is that consumers generally are less able to absorb shocks, just as uncertainty is soaring. It is hard to blame them for turning cautious, even if that means the economy suffers.

So shorter: Mr. Market and the Confidence Fairy were keeping the economy chugging along, even if it was not widely recognized as a two tier enterprise. Now Trump has managed to whack them both, hard. Remember, a surprising trend since the crisis is the degree to which even the moderately to very wealthy would borrow against assets. Falls in asset prices put a hard brake on that as an additional booster.

A new Axios story, Voters disapprove of Trump’s economic policies, polls show, explains why the public view of Trump’s schemes has soured:

The big picture: The ramifications of Trump’s policies are already rippling outwards and impacting businesses and communities.

- The National Federation of Independent Business’s uncertainty index for small businesses rose to it’s second-highest reading ever last month since the 1980s, and many small businesses report raising prices, MarketWatchreported.

- In fact, a slew of small business owners have spoken out about the detrimental impacts Trump’s tariffs will have on their ability to maintain their businesses.

- Delta, Southwest and American airlines all warned this week that their first-quarter revenue or earnings forecasts will fall below expectations due to weaker consumer demand.

Our thought bubble, from Axios’ Ben Berkowitz: Investors are beginning to realize the first-term “Trump put” — the notion that he’d change policy if markets reacted negatively — isn’t in evidence this time around.

- There’s a greater willingness by his team to let whatever happens happen, which is an adjustment to past Trump economic practice that’s coming as a shock to some people.

Recall that the mother of all shock doctrines, Pinochet’s 1975-1975 program, which unlike the Trump program, did produce some initial promising results, eventually led to damage so severe as to lead Pinochet to go hard into reverse.1 As we have seen repeatedly (particular tariff threats, the Ukraine negotiations, Trump ritually beating up on Bibi before shoring him up, Iran) Trump seems to relish making radical reversals simply because he can. But how much ego investment does he have in his tariff and Federal institution destruction program? He’s rhapsodsized so much about how wonderful it was in the great pre-electricity, barely-any-indoor plumbing Gilded Era that one can expect him to be far less responsive than he has on his other pet project. I’d like to see we’ll see soon enough, but we may not.

______

1 From ECONNED:

Chile has been widely, and falsely, cited as a successful “free markets” experiment. Even though Chilean dictator Augusto Pinochet’s aggressive implementation of reforms that were devised by followers of the Chicago School of Economics led to speculation and looting followed by a bust, it was touted in the United States as a triumph. Friedman claimed in 1982 that Pinochet “has supported a fully free-market economy as a matter of principle. Chile is an economic miracle.” The State Department deemed Chile to be “a casebook study in sound economic management.”

Those assertions do not stand up to the most cursory examination. Even the temporary gains scored by Chile relied on heavy-handed government intervention….

The “Chicago boys,” a group of thirty Chileans who had become followers of Friedman as students at the University of Chicago, assumed control of most economic policy roles. In 1975, the finance minister announced the new program: opening of trade, deregulation, privatization, and deep cuts in public spending.

The economy initially appeared to respond well to these changes as foreign money flowed in and inflation fell. But this seeming prosperity was largely a speculative bubble and an export boom. The newly liberalized economy went heavily into debt, with the funds going mainly to real estate, business acquisitions, and consumer spending rather than productive investment. Some state assets were sold at huge discounts to insiders. For instance, industrial combines, or grupos, acquired banks at a 40% discount to book value, and then used them to provide loans to the grupos to buy up manufacturers.

In 1979, when the government set a currency peg too high, it set the stage for what Nobel Prize winner George Akerlof and Stanford’s Paul Romer call “looting” (we discuss this syndrome in chapter 7). Entrepreneurs, rather than taking risk in the normal fashion, by gambling on success, instead engage in bankruptcy fraud. They borrow against their companies and find ways to siphon funds to themselves and affiliates, either by overpaying themselves, extracting too much in dividends, or moving funds to related parties.

The bubble worsened as banks gave low-interest-rate foreign currency loans, knowing full when the peso fell. But it permitted them to use the proceeds to seize more assets at preferential prices, thanks to artificially cheap borrowing and the eventual subsidy of default.

And the export boom, the other engine of growth, was, contrary to stateside propaganda, not the result of “free market” reforms either. The Pinochet regime did not reverse the Allende land reforms and return farms to their former owners. Instead, it practiced what amounted to industrial policy and gave the farms to middle-class entrepreneurs, who built fruit and wine businesses that became successful exporters. The other major export was copper, which remained in government hands.

And even in this growth period, the gains were concentrated among the wealthy. Unemployment rose to 16% and the distribution of income became more regressive. The Catholic Church’s soup kitchens became a vital stopgap.

The bust came in late 1981. Banks, on the verge of collapse thanks to dodgy loans, cut lending. GDP contracted sharply in 1982 and 1983. Manufacturing output fell by 28% and unemployment rose to 20%. The neoliberal regime suddenly resorted to Keynesian backpedaling to quell violent protests. The state seized a majority of the banks and implemented tougher banking laws. Pinochet restored the minimum wage, the rights of unions to bargain, and launched a program to create 500,000 jobs.