The German political establishment is so gripped by paranoia over Russia that Chancellor Olaf Scholz is now being compared to Neville Chamberlain:

As a member of the “Scholz is the new Chamberlain” crowd—what the German debate over support to Ukraine regularly misses is this isn’t an abstract discussion.

What Germany decides to do (or not) has real strategic and human consequences for Ukraine, Germany & Europe. https://t.co/RkLQPe1Vpa

— Aaron Gasch Burnett (@AaronGBurnett) March 29, 2024

This is the environment in which German opposition figure Sahra Wagenknecht’s new party will test its platform in the June European Parliament elections. (It will also get to measure its appeal in state elections in Saxony, Thuringia and Brandenburg in the fall.) A key part of that platform is opposition to war against Russia, which Wagenknecht made clear in a recent Bundestag speech:

“Have you all lost your minds?”.

Amazing and terrifying speech by @SWagenknecht on the folly of Germany’s warmongering approach to Russia. pic.twitter.com/wfOV1ebzoO

— Thomas Fazi (@battleforeurope) March 17, 2024

Aside from Ukrainians, the war against Russia has arguably hurt working class Germans more than anyone else. Despite that fact, Wagenknecht is labeled a “Putin appeaser” and one with “sympathies towards Russia” for her opposition.

It’s also means that how the party steered by Wagenknecht – Reason and Justice (BSW) – fares in the European elections, and what it does afterwards will be interesting to watch.

BSW is projected to become the largest left delegation within the European Parliament after the June vote, and she is reportedly planning an attempt to form a new parliamentary group – one that could effectively demolish the existing moribund Left Group.

The Wagenknecht Platform

Wagenknecht’s “left-wing conservativism” would mean a left less focused on identity issues while prioritizing working class economic issues. While not opposing immigration on any racial grounds, she acknowledges voters’ concerns that too much immigration can be problematic: “people are experiencing a lack of housing, teachers are overworked, children can’t speak German and there are cultural conflicts.”

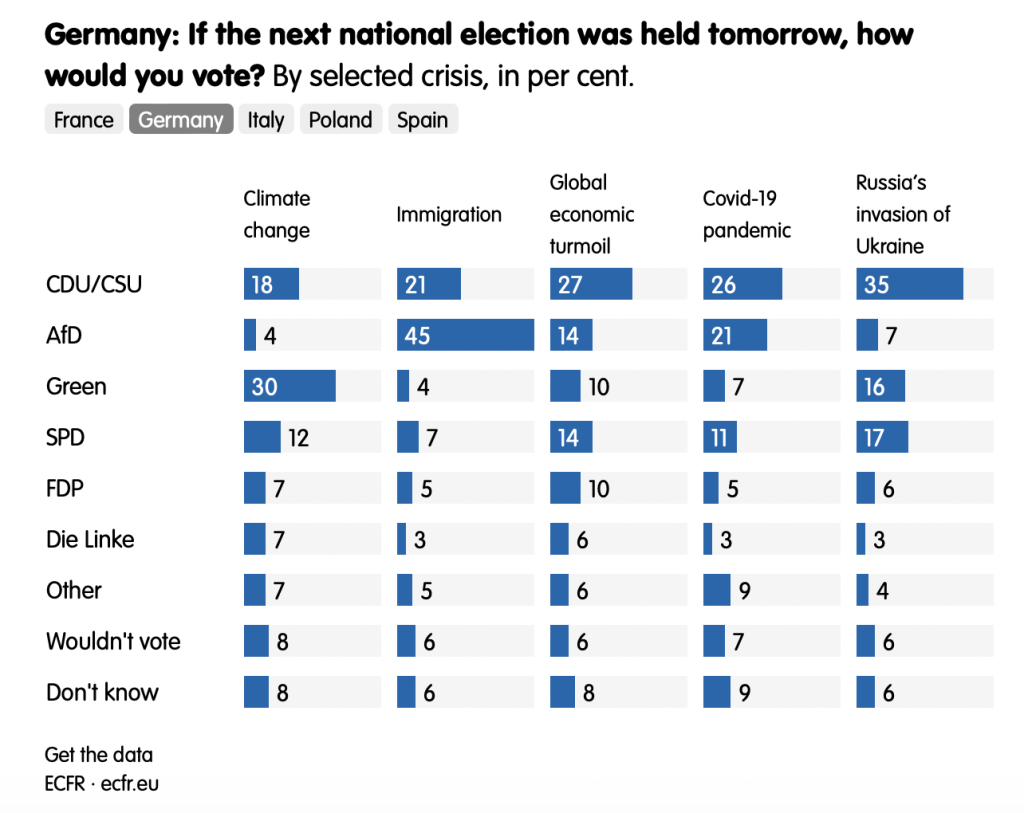

Wagenknecht gets a lot of criticism for her stance on immigration, but the fact is that’s what German voters are most concerned about:

And it’s what has led to the rise of the Alternative for Germany (AfD), a party that has fascist elements at its core:

Both the AfD and Wagenknecht’s BSW are in favor of reclaiming German sovereignty from the EU and the US/NATO and acting in Germany’s national interest, which would mean ending its participation in the economic war against Russia that has done far more damage to Germany. They also both favor rethinking German immigration policy.

The struggle for Wagenknecht is drawing distinctions between the two parties. To do so, BSW is focusing on three lines of attack:

- That BSW is the true representative of the working class while AfD opposes globalists in favor of a more national oligarchy. (The AfD, after all, did receive its seed money from a Nazi billionaire family.) BSW likes to point out AfD’s hypocrisy in supporting the recent farmers protests in Germany while the party’s program simultaneously calls for removing farmer subsidies. “This is not an anti-system party. It is the system, but undemocratic and mean,” says BSW General Secretary Christian Leye.

- That the AfD opposes immigration on racial grounds that harken back to some dark chapters in German history while BSW wants common sense approaches that would benefit the German working class.

- The BSW also describes itself as the only consistent peace party in the Bundestag. The AfD, on the other hand, is not at all opposed to militarization. In fact, the party calls for the full restoration of operational readiness of the German armed forces. The AfD’s problem is that the US/NATO exercise too much control over the German military without taking into account German national interests.

Here’s more on Wagenknecht’s European elections platform from Table Europe:

The leitmotif of the program is: “Less is more.” The BSW strives for an “independent Europe of sovereign democracies.” The integration of Europe “in the direction of a supranational unitary state has proven to be a mistake.”

The BSW wants to prevent wage dumping in the internal market and is calling for the introduction of a European minimum wage. A postulate that the Left Party also has in its program. The demand for an excess profits tax in the industrial sector and a reform of the debt brake is also common to both parties. The power of large corporations such as Google or Amazon must be restricted, said De Masi. The BSW is calling for an end to energy sanctions against Russia. They were not harming Putin, but Germany.

De Masi left out the topic of migration in his speech. The program remains relatively vague on the subject: illegal migration must be stopped and prospects in the home countries improved, it says. The right to asylum is not called into question. However, immigration should not overburden local capacities.

Who Supports BSW?

Mainly working class voters opposed to the Ukraine War.

The ZDF political barometer from February shows that while a little more than 50 percent of respondents rated their economic situation as “good,” just under one in three BSW supporters say the same. And nearly half of BSW supporters believe that they will be worse off in a year than they are today. At the same time, while a majority of respondents were in favor of supplying more weapons to Ukraine, among BSW supporters it was less than 40 percent.

If those numbers seem high, it’s probably a sign of the atmosphere in Germany where those opposed to sending Ukraine missiles capable of reaching Moscow are labeled Neville Chamberlain.

Plans are in the works for Wagenknecht’s party to form a left contingent in the European Parliament opposed to the Russia policy and steer it away from the party she left, Die Linke (The Left), which has completely collapsed after abandoning nearly all of its former working class platform in favor of identity politics in an attempt to appear “ready to govern.” Much like the Greens, The Left increasingly stands for neoliberal, pro-war and anti-Russia policies.

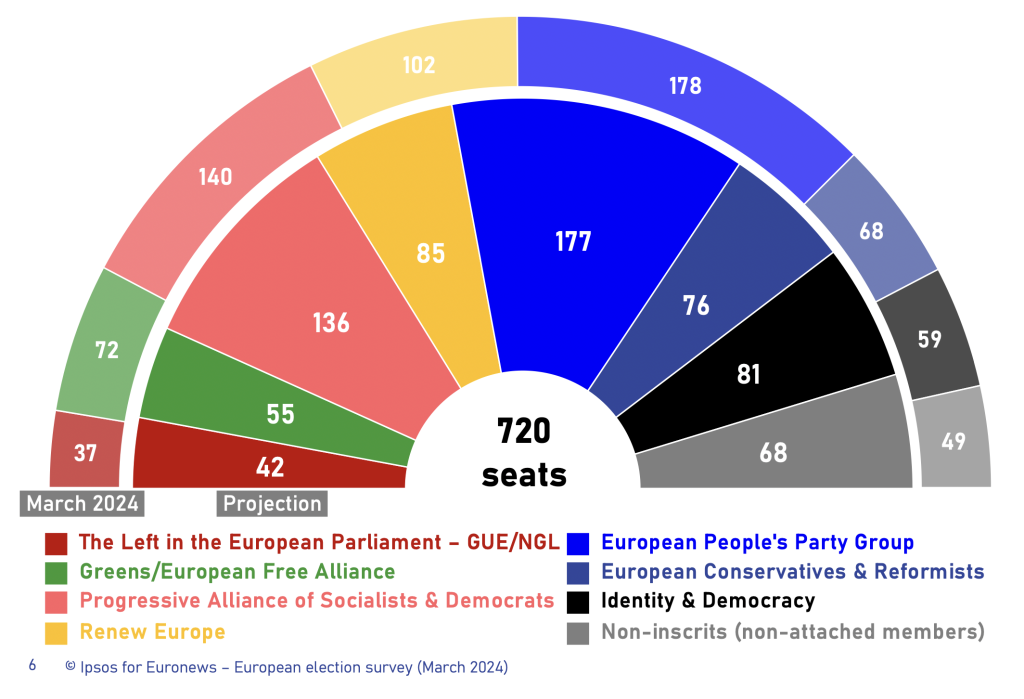

To form a new parliamentary group within the chamber, Wagenknecht would need 23 MEPs from seven EU countries. Who are its potential allies?

BSW representatives have confirmed prospective talks with France’s La France Insoumise. Other European Parliament members opposed to Project Ukraine are possibilities. Slovakia’s ruling Smer party, for example, was recently suspended from the Progressive Alliance of Socialists and Democrats group in the parliament for questioning NATO and its social conservatism.

A hostile takeover of the current left delegation is also a possibility as there may not be enough MEPs to sustain two separate left-wing factions. According to The European Conservative:

Tactically, the German politician has not ruled out joining the current parliamentary Left faction—becoming the effective kingmaker within—and could simply be using the threat of a new group as leverage.

Regardless, Wagenknecht’s BSW will likely be another thorn in the side of von der leyen (should she remain as European Commission president). We could always use more of this:

Irish MEP Clare Daly called Ursula von der Leyen “Frau Genocide.”

“Ursula von der Leyen is a figure no member of the public ever voted for, who’s spent the last three months swooping in and speaking over the foreign policies of elected governments, all to cheer-lead for a… pic.twitter.com/Atz4HXgX6r

— Joe Quinn (@SeosQuinn) December 26, 2023

Criticism from All Sides

Wagenknecht’s BSW doesn’t just get it from what’s now referred to as the German “center” (i.e., the parties of warmongers and anti-working class policies).

It also gets a lot of criticism from the left – especially on the immigration issue.

They say that Wagenknecht’s party is just another flavor of capitalism and criticizes the party for its declared willingness to work with other parties to advance its issues. That is not the solution; according to WSWS, it is the following:

The only way to oppose militarism, prevent a third world war and defend social rights is through the international mobilisation of the working class against capitalism. No problem can be solved without breaking the power of the banks and corporations and bringing them under democratic control. Such a movement requires the unification of workers across all national, ethnic and religious boundaries.

While this is at least genuine, the disingenuous criticism from liberal identity wings is that Wagenknecht is “anti-vanguard” for ignoring identity issues in favor of class-based politics. In their eyes this makes her right wing (and even comparable to Benito Mussolini). These arguments are representative of the fear that the return of a class-based left would crash the cushy party of a finance-centered political economy that is welded to the politics of recognition.

There’s an argument to be made that Wagenknecht’s brand of politics is one hope at containing the rise of the far right, and it’s one that Wagenknecht makes herself:

Wagenknecht also blames the government for the rise of the AfD. Any criticism of politics is immediately defamed as right-wing, as was recently the case with the farmers’ demonstrations. We already know this from the protests during the Covid pandemic. “If people have been told for years that any reasonable criticism is right-wing, then it’s no wonder that a right-wing party is successful.” The fact that the traffic light politicians are now taking to the streets at anti-AfD protests is absurd. “If they really want to weaken the AfD, they don’t need to demonstrate, they need to finally change their miserable policies.”

Not only is Berlin ignoring that advice, but the same is true across Europe where the overall picture is one of an ascendant right. Right-wing parties are expected to win the election in six of the EU’s 27 member states, including France and Italy.

It’s a strong possibility that a right-wing coalition will take the reins in the parliament for the first time in its history. There is however, a lot of variation on the right – especially on the issue of Ukraine. Some are true believers, others were against the EU/NATO before they were for it, and others still oppose the war against Russia.

The European Peoples Party, which is projected to remain the largest bloc in the parliament, is a major backer of Project Ukraine. The European Conservatives and Reformists (ECR) is too. ECR is led by Brothers of Italy, Law and Justice in Poland, VOX in Spain, and the Sweden Democrats.

The opposition to Project Ukraine can be found on the right in the Identity and Democracy (ID) party, although it might be softening – at least in the case Rassamblent National:

The Melonisation — i.e., self-domestication — of Le Pen proceeds apace. After giving up on her anti-euro platform, she’s now appeasing NATO and Washington. She’s almost ripe for being allowed to govern. pic.twitter.com/efTTROq3wp

— Thomas Fazi (@battleforeurope) March 14, 2024

Germany’s AfD and Lega in Italy continue to hold onto their opposition to the economic war on Russia and are constantly hammered by spooks, media, think tanks, and politicians over it. Nonetheless, ID, which also includes Geert Wilders Party for Freedom and Austria’s Freedom Party, is projected to become the third largest EP grouping, up from its sixth-place finish in the elections of 2019.

At the end of the day, the sad reality is that parliament has a limited ability to do much other than provide a facade of democracy. The parliament is supposed to act as a check on commission power. It has to approve legislation proposed by the European Commission, it can censure the Commission, and the European Council has to ‘take into account’ the result of the parliament elections to nominate the Commission president – although the latter process turned into a backroom disaster in 2019 when Ursula von der Leyen failed upwards into the job.

EU leaders dismissed all the parties’ candidates and surprisingly elevated Ursula von der Leyen, who had not featured in the race and was doing a poor job as Germany’s defense minister.

As president of the European Commission, she holds sweeping powers on a range of issues, including tech, healthcare and social rights. Recent polling shows that a majority of voters (63 percent) either view the Commission’s work negatively or have no opinion.

Nonetheless, von der Leyen looks like the odds-on favorite to return to the job and continue her reign.