Yves here. This study looks at an important topic: what causes inequality of health by income strata? It’s widely recognized that richer people generally have better health than poorer people, but how does that come about? This data comes from Denmark, which has a very good health system that offers high quality care to lower income groups. The big findings are that poorer people suffer from chronic ailments at a higher level and younger than the more affluent. This is not primarily due to a care gap. Once a condition is diagnosed, the outcomes are similar by income group. However, the authors point out that conditions may be diagnosed later among the less well off, so they might have been spared having a chronic condition if there was better preventative care.

The article does not unpack the degree to which environmental factors, like living in areas that can directly impair health (poor air quality via living near big traffic arteries, more exposure to toxins via living near chemical plants) or in jobs that can harm health contributed to the health differential. Readers can tell me the degree to which lower income Danes might wind up eating less healthy food, which in the US is a big contributor to obesity.

Of course, the causality runs the other way too: that those afflicted with chronic conditions could find it harder to wind up on a higher income track.

By Kaveh Danesh, Internal medicine resident University of California, San Francisco, Jonathan Kolstad, Associate Professor, Haas School of Business University of California, Berkeley, William Parker, PhD candidate London School Of Economics And Political Science, and Johannes Spinnewijn, Professor in Economics London School Of Economics And Political Science. Originally published at VoxEU

Though health disparities have long been the subject of research and debate, life expectancy gaps between rich and poor remain striking, even in countries with universal access to healthcare. This column analyses the roots of health inequality using data from the Netherlands. While mortality differences are most apparent at old-age, chronic illness starts shaping these inequalities much earlier in life than commonly recognised. Socioeconomic status and geographic disparities play a critical role in chronic disease development, surpassing the impact of unhealthy behaviours such as smoking and drinking.

In the Netherlands, healthcare access is approximately universal, with just 0.4% of poor households reporting unmet medical needs (Eurostat 2023). However, inequality of life expectancy remains pronounced: across the household income distribution, the gap is 7.6 years for women and 11.6 years for men. This is consistent with figures elsewhere in Europe, and little better than results from the US (Chetty et al. 2016, Schwandt et al. 2021, Currie and Schwandt 2016, Bohacek et al. 2018).

Despite the importance of the issue and the attention paid in policy and research, the complexity of the health production function in combination with measurement challenges have limited our understanding of what drives health inequality. As Angus Deaton has observed: “there is no general agreement about its causes … and what apparent agreement there is, is sometimes better supported by repeated assertion than by solid evidence” (Deaton 2002).

Our new research (Danesh et al. 2024) focuses on chronic illness to study how health inequalities develop over the lifecycle. Chronic illness is not only a key contributor to the mortality-income gradient, but also a measurable, dynamic marker of population health (Bloom 2022). As such, it allows us to track a key measure of health that contributes to mortality gaps in older age, long before these mortality effects manifest themselves. Building on prior work (e.g. Huber et al. 2013), we use dispensed medication to identify chronic conditions. These data are available at the individual level for the entire Dutch population since 2006. We directly address concerns regarding unequal underdiagnosis and/or inadequate management of chronic conditions, using additional information from survey data and other medicine use. We find that detection and medication rates are consistent across the income distribution, except for the very bottom 5%–10%.

Figure 1 plots the prevalence of all chronic diseases at old-age and highlights their higher prevalence for individuals with below-median household income. We separate out the bottom 10% (D1), illustrating the lower prevalence of some conditions (e.g. cardiovascular disease) for this group, likely due to under-diagnosis and/or management. Overall, we find that differential prevalence of chronic conditions can explain 30–40% of the gap in old-age mortality between low- and high-income groups. Moreover, we do not find meaningful differences in mortality conditional on chronic disease, suggesting that individuals diagnosed with a given chronic condition receive treatment of similar quality irrespective of their income group. This is further corroborated by similar healthcare expenditures conditional on chronic conditions across the income distribution.

Figure 1 Differences in chronic disease prevalence by income at age 70

Dynamic Forces Behind the Mortality Gap

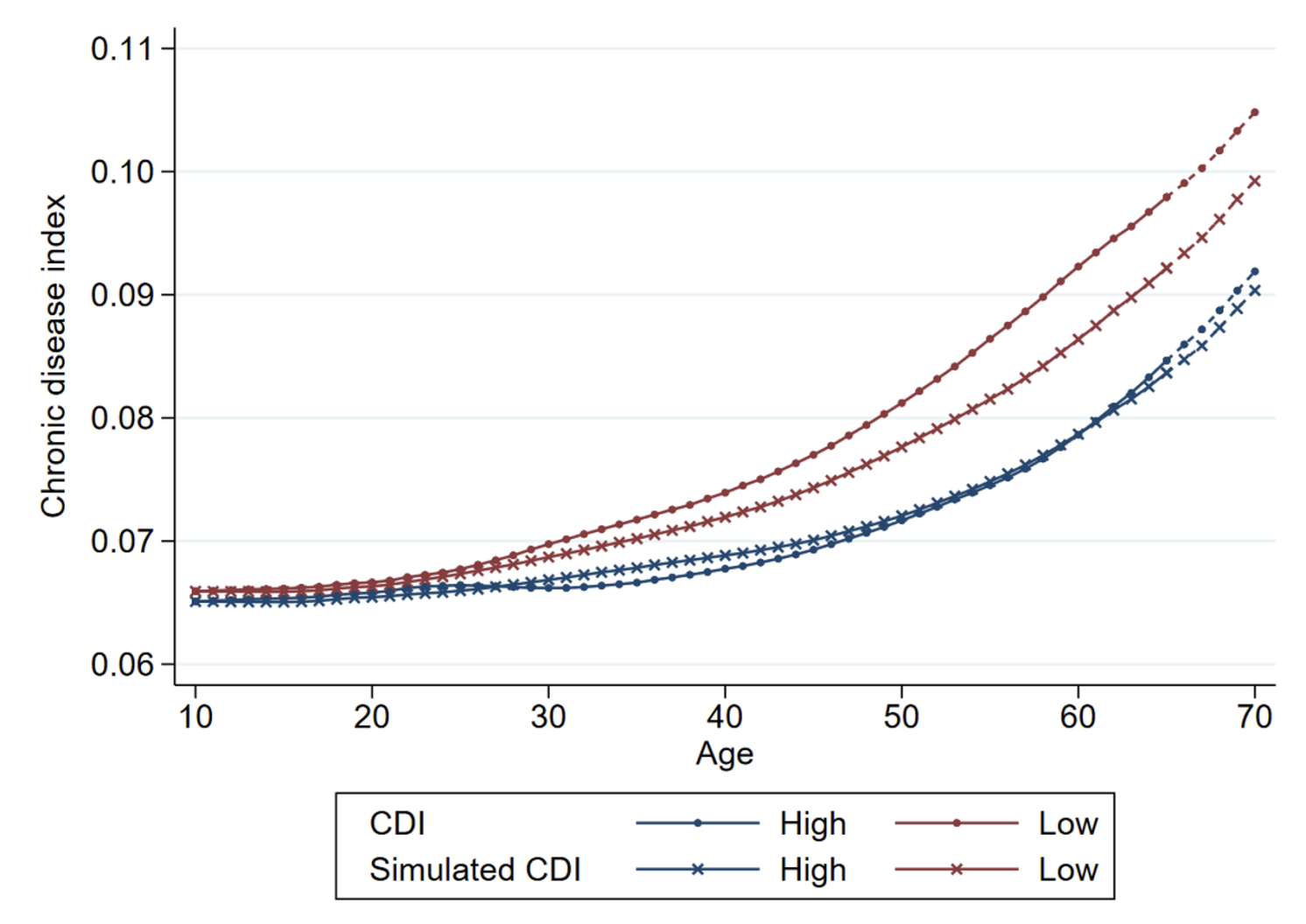

While gaps in mortality risk are most apparent post-retirement age, our analysis shows these forces are well established earlier in life. We construct a Chronic Disease Index (CDI) for all individuals and at all ages, capturing how their point-in-time chronic conditions would jointly predict mortality risk at old-age. Figure 2 visualises how the average CDI evolves over the lifecycle, for low- and high-income individuals separately. The dynamic series reveals that half of the measured gap at age 70 has already materialised at age 40, indicating the need for early interventions to close the health gap.

Two primary forces drive the rise in the health gap with age: differential ageing, whereby low-income individuals develop chronic illness at a faster rate; and health-based sorting, whereby chronically ill individuals sort into low-income groups. Figure 2 also shows the simulated CDI excluding the health-based sorting effect, and highlights that more rapid ageing among low-income individuals occurs in early adulthood. Though both forces are significant, our estimates indicate that differential ageing is the dominant factor: it contributes 40% more than health-based sorting to the gap in chronic disease burden at age 70.

This underscores how individuals in different income groups experience distinctive health trajectories, and the need for interventions to deal with the social determinants of health at an earlier age. Focusing on the role of single chronic conditions, we find that the differential incidence of cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and respiratory disease contribute most to differential ageing throughout adulthood. We also see substantial differences in the prevalence of psychological disorders contributing most to the gap in CDI levels already at young ages.

Figure 2 The health gap over the life cycle

Mediators of Chronic Disease

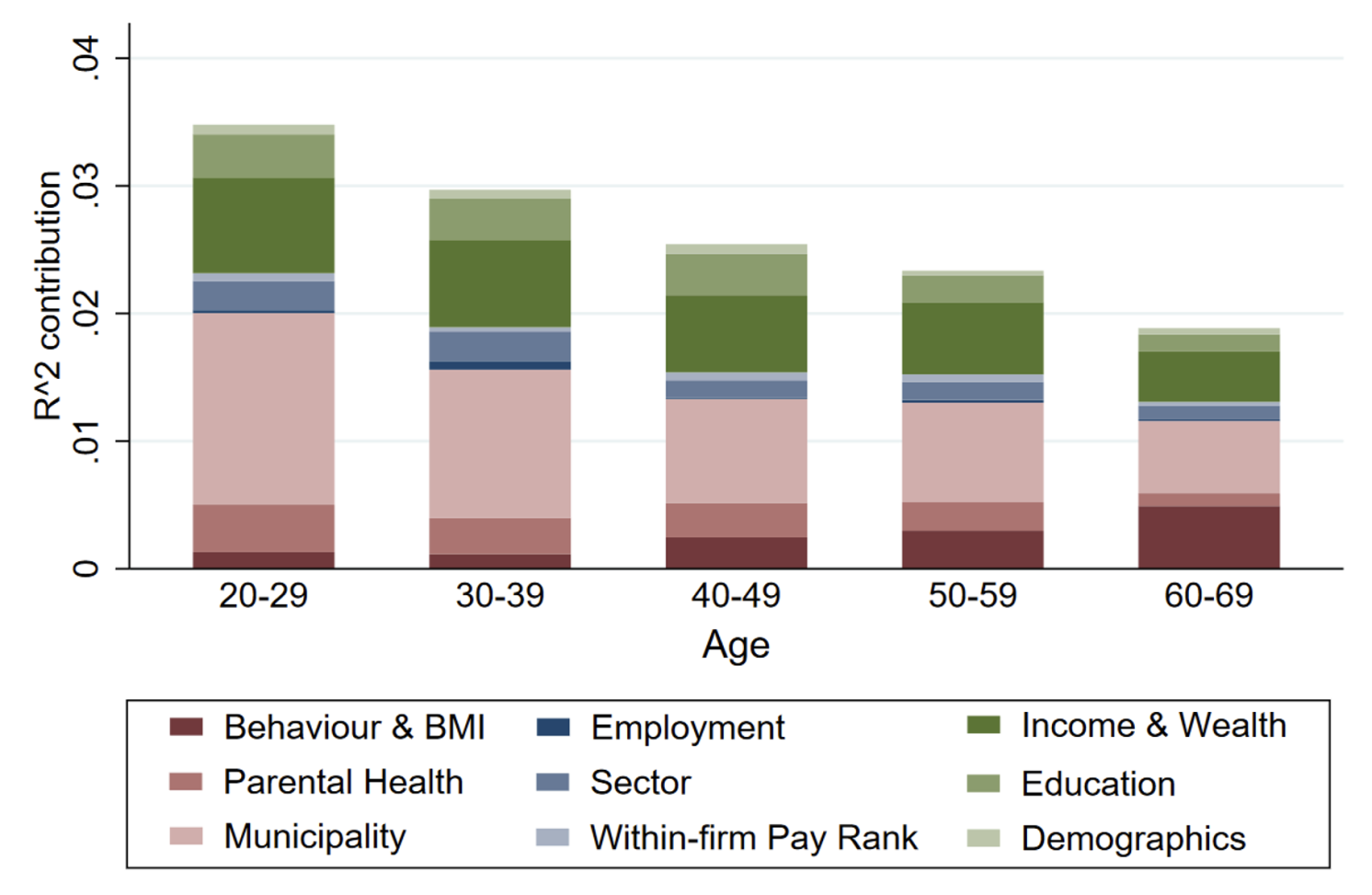

Having established the difference in health trajectories, we can also shed light on the relevant factors mediating these trajectories. We leverage the rich data environment in the Netherlands, which includes not only various administrative registers, but also linked survey data. In contrast with prior work, we can account for a range of mediating factors jointly in the same context, and thus provide a comprehensive account of their relative importance. Using Shapley-Owen decompositions, which apportion the commonly explained variation by different mediators, we find that socioeconomic status and geography contribute most to the explained variation in the incidence of chronic conditions, accounting for about one third each. Figure 3 illustrates these findings. In contrast, we find a less important role for observed health behaviours (i.e. smoking, drinking, exercise, body mass index) and occupational factors (e.g. sector of work, within-firm pay rank).

While this analysis is descriptive, it provides an important recalibration of the potential importance of different determinants of health, as prior work emphasised individual health behaviours as the key driving factor (e.g. McGinnis et al. 2002). Interestingly, the richness of the data allows us to illustrate the potential for misestimation due to data challenges. In particular, we show that a more partial analysis (e.g. not controlling for other social and geographic factors) or the failure to account for reverse causalities (e.g. studying prevalence rather than incidence) would overestimate the importance of commonly measured health behaviours.

Figure 3 Relative importance of mediators for five-year growth in CDI

Conclusions and Policy Implications

In many countries, healthcare spending is directed almost entirely towards treatment, despite the high returns to prevention. By showing their potential to reduce the health gap, our analysis strengthens the case for investments in preventive policies. In particular, our research demonstrates that differences in the incidence of poor health conditions are a more significant driver of health disparities than differences in treatment. Moreover, we find that health inequality begins much earlier in life than traditionally recognised, with significant disparities already apparent at middle age. The primary driver is differential ageing across the income spectrum, to the detriment of low-income people. Addressing this disparity early in life is essential for reducing health inequality.

Effective policy should focus on interventions targeting the early-life determinants of health, and move beyond the current focus on unhealthy behaviours such as smoking and drinking. In particular, socioeconomic status and geographic disparities play a critical role in chronic disease development, surpassing the impact of individual health behaviours. Comprehensive strategies that address these factors before they translate into chronic disease are essential to creating a more equitable health landscape.

See original post for references