Yves here. The Bank of England and Fed are engaged in economic malpractice on a large and increasingly dangerous scale. The Fed did recognize that its post-crisis experiment with super low interest rates was producing economic distortions and dysfunction (some contacts say as early as 2012). But when Bernanke tried backing out in 2014, he got the famed Taper Tantrum and lost his nerve.

So when Covid hit, and with it, sticker shock in particularly affected sectors like cars, food, and lumber (compounded by the bad luck of an avian-flu mass chicken cull), and then sanctions-blowback-induced energy price increases, the Fed waded in to fight inflation, even though, as we pointed out, the result of using the hammer of interest rate increases would be to kill the economy. There are much more targeted approaches,1 starting with designing more spending to be countercyclical. But nearly all require political will when it’s so much more convenient to let unelected central bankers do the heavy lifting, even with their handiwork being predictably pretty poor…unless the object is further reducing worker bargaining power and standards of living.

But as we and others predicted. the use of the wrong medicine for this inflation meant central bankers would have to keep interest rates high for a comparatively long time. Even though the Fed did signal its intent to raise rates pretty aggressively, many banks and investors were wrong-footed. It isn’t crazy for regulators to let banks get away with not recording most of their mark to market losses if there are good odds of the central bank lowering rates out of nosebleed territory fairly soon. But if that does not happen, banks start reporting income statement losses. And high rates in an economy not prepared it will also produce credit losses as borrowers have to roll maturing debt and can’t get it at the price and quantity they need.

With all that said, the UK could be the canary in the coal mine. It was already suffering from lower growth than pretty much everyone in the EU due to Brexit effects. It also experienced serious energy and food inflation last fall and early winter. UK banks’ total assets are somewhat down relative to GDP compared to the level before the global financial crisis (by memory, around 450%). But they are still high on a comparative basis. From HelgiLibrary:

If any UK banks start looking green about the gills, it’s not hard to see concerns rising here, due to questions about whether any US players were similarly situated plus contagion concerns. And if that were to start, increases in funding costs can create a down spiral. I’m not saying that is happening yet but the potential is there, particularly if the Fed does not ease up.

By Richard Murphy, part-time Professor of Accounting Practice at Sheffield University Management School, director of the Corporate Accountability Network, member of Finance for the Future LLP, and director of Tax Research LLP. Originally published at Tax Research

The economic outlook appears to be even poorer this morning.

Those renting are having a torrid time. Rents are up at least 10% in the past year.

Those who can get a property are accessing some of the poorest housing stock in Europe.

The government is going to make things worse. They plan to solve the refugee processing backlog by releasing 50,000 into the community without support, many of whom will then become homeless.

And things are little better for homeowners. MetroBank is in financial crisis (although that’s being talked down). The bank has a loan book that few think of the highest quality. That is why its value has fallen to £100 million. The problem for it is it needs to refinance £350 million of its own loans in the next year, and raise £250 million in extra capital. There is, I suggest, no way that it can survive that dual demand in its existing form. A white knight will have to be found, and that is always a sure sign of an impending financial crisis. Just think back to 2008.

That is not the only problem for banks. As the FT has noted, bank third quarter earnings look like they will be hit hard by the fall in the value of their bond holdings as markets take the impact of long-term high-interest rates into account. Since interest rates and bond values are pretty much the inverse of each other, those rates are now hitting the value of bank balance sheets hard, just when their mortgage and loan portfolios are severely threatened by bad debt risks, also created by high-interest rates.

Those bad debt risks are, of course, the consequence of personal and business debt crises as high interest rates hit. So, there are further threats of homelessness whilst unemployment is bound to rise.

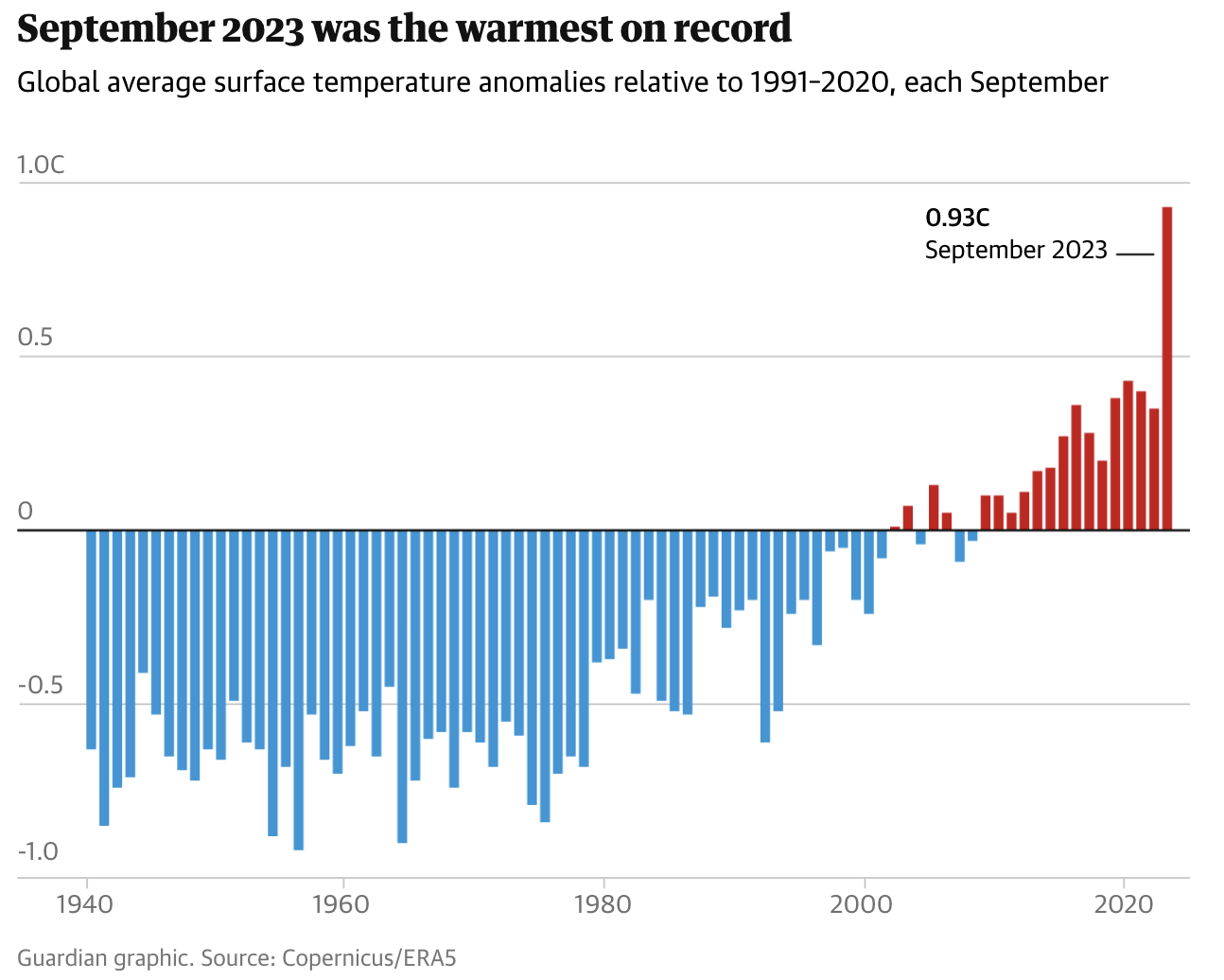

And let me add some more misery into the mix. September was totally abnormally hot:

That’s not just aberrational: it is staggeringly abnormal, and that is continuing. I am writing this in the open air and just shirt-sleeved at 8.20 in the morning in October, with 25 degrees forecast for the south at the weekend. The scale of investment required to manage this is also off the scale.

So what does all this mean?

First, it means that the Bank of England policy of high-interest rates is working as I predicted it would, to crash the economy. That did not require me to be an exceptional seer: the Bank of England wanted this to happen to crush demand in the economy and is getting what it wanted. I just had the honesty to call it out. The crisis we face is not necessary: it is being manufactured in Threadneedle Street.

Second, the cost of this is not going to be some little blip in the economy. This moment now feels like 2007 – when everything began to go wrong but few said it (again, I was one of the exceptions). It feels like everything could totter over soon, with calamitous (I do not use the word lightly) consequences.

Third, no one is getting ready for this. The Bank of England is talking about selling £100 billion of its bond portfolio in the next year as part of its quantitative tightening programme as part of its programme to maintain high interest rates when the reality is that it should be planning for the emergency support that the economy is going to need, soon.

The Tories are playing games. The whole focus of their conference was putting spanners in Labour’s works: HS2 abandonment apart, nothing they announced will have the slightest consequence before they are out of office.

And then there is Labour. This weekend will be interesting only for the sentiments on display. If they win today’s by-election in Scotland they will be buoyant. If not (and you can guess where I stand on that) they will be hunkering down before even reaching office.

My suspicion is that they will win because there is always a backlash against a sitting MP who has failed. In that case, expect talk of them saving pubic services without spending a penny on them because fiscal rules will be referred to time and again, whilst nothing of substance will be said because (as Pat MacFadden has tediously said, yet again, this morning) they ‘need to see the books’ before deciding on anything. It is as if imagining what might be revealed is a task way beyond their ability.

Fourth, then, there is the real need. That is for an economic redesign. I mentioned the need for innovation around what is possible yesterday. Nowhere is that more apparent than in the economy itself.

We need to cut interest rates because that is possible and would cut inflation. It is economically counter-cultural, but when convention is very obviously not working what is wrong with that?

We also need to raise taxes on the wealthy for three reasons. The first is that the government needs to spend more as a proportion of GDP in both the short and long term and that will require that the inflationary impact of that spending be removed from the economy by making extra demand on those best able to meet it.

The second reason is that income has to be redistributed into the hands of those who need it if they are to survive the stresses to come.

And third, when markets are failing to direct savings towards real investment – which they are so obviously not doing – the state will have to intervene to achieve that goal.

What we then need is a plan for the required spending. It will not be possible to cut our way out of the crisis to come – at least not if the lives of the people of this country matter – so there have to be such spending plans.

My great fear is that Labour is doing none of this thinking. It is not even aware, I suspect, that it is required even though this crisis is going to emerge on their watch unless something very unexpected happens to save them.

We are already in the proverbial creek. My fear is that no one in charge knows where the paddle is. And that is really scary.

____

1 Notice how the media does not take up this idea much? Nevertheless, one example from ABC Australia, Beat inflation without raising interest rates? We can do it, but it’s slow, hard and politically risky.