Yves here. This factory building trend, sighted by Wolf Richter, bears watching. It’s a concrete demonstration (pun intended) that there is a serious effort underway to “reshore” manufacturing. However, desire and spending do not necessarily translate into results. Recall the great hyped Foxconn factory in Wisconsin, where they sucked lots of subsidies out of the state and then punted. From CNBC in 2021:

Taiwan electronics manufacturer Foxconn is drastically scaling back a planned $10 billion factory in Wisconsin.

Under a deal, Foxconn will reduce its planned investment to $672 million from $10 billion, and slash the number of new jobs to 1,454 from 13,000.

And remember, this is an established player, as in Foxconn knows how to start up and operate factories. This is not Americans who might be scrambling to find desperately needed factory floor supervisors and higher level manufacturing managers.

Wisconsin did at least restructure the deal and clawed back a lot of the subsidy commitments.

Similarly, Alexander Mercouris has reported long form on the failed US effort to increase 155 mm shell production. In addition to many mishaps which he recounted long form, the bottleneck remains a lack of gunpowder. There seems to be only one factory, in Poland, that makes TNT. The US had decided to move off TNT because environmentally nasty, but the replacements never worked (not sure because they failed as explosives or were too hard to produce at scale and/or reasonable cost).

Admittedly, it’s a somewhat different type of manufacturing, but I was a paper mill brat and my father ran paper mills. Coated paper is very fussy. The coating, in his day mineral clay, is applied when the paper is wet. The paper machines have to operate at very fine tolerances or else the paper breaks, causing costly downtime.

The mills have to run 24/7 except for scheduled maintenance because the capital costs are high.

My father ran startups and turnarounds because hardly anyone in the industry could execute them. He eventually became the head of manufacturing at one of the major papermakers.

The rule of thumb was a successful startup (of a single “machine” as in production line, which cost ~$500 million in 1970s) took two years and cost 20% of the capital costs. An unsuccessful startup was a running money sore.

In other words, erecting factory buildings is the easy part. Stay tuned as to how high the successful opening and production rate is.

By Wolf Richter, editor at Wolf Street. Originally published at Wolf Street

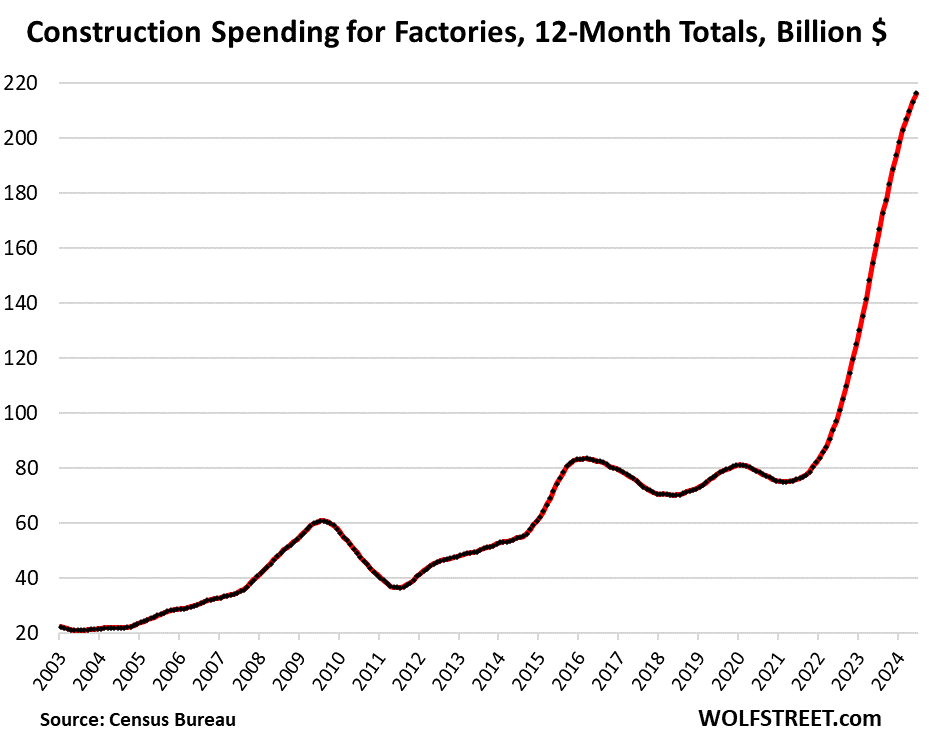

Companies invested a record $19.7 billion in June in the construction of manufacturing facilities, up by 18.6% from the already surging levels in June 2023, up by nearly 100% from June 2022, and up by 209% from June 2019, according to the Census Bureau today.

The investment totals here only cover the actual construction costs of the facilities, not the costs of the manufacturing equipment and installation that can dwarf the construction costs of the building. The total cost of a big chip plant might reach $20 billion, but the construction costs are the smallest part of it. So the total amounts invested in manufacturing plants, including the equipment and installation, are much higher. But here, the amounts only refer to the construction of the plants, and can be seen as a directional indicator of total investment in manufacturing.

In addition to the construction boom of semiconductor plants, a large number of other manufacturing plants have been announced, and continue to be announced.

The explosion in factory construction that started in the second half of 2021 was one of the changes that came out of the pandemic when America’s scary dependence on China became apparent in massive shortages of all kinds of goods, including semiconductor shortages, and unbelievable supply-chain and transportation chaos, that caused corporate America and policy makers to rethink the strategy of endless globalization.

The CHIPS Act, signed into law in August 2022, was part of the movement. While the first awards have been announced, there is lots of stuff left to do, including due diligence, and the cash hasn’t been disbursed yet. That’s still to come.

The 12-month total of investment in manufacturing plants jumped to $235.5 billion, up by 19% from the same period a year ago, up by 100% from two years ago, and up by 217% from the same period in 2019.

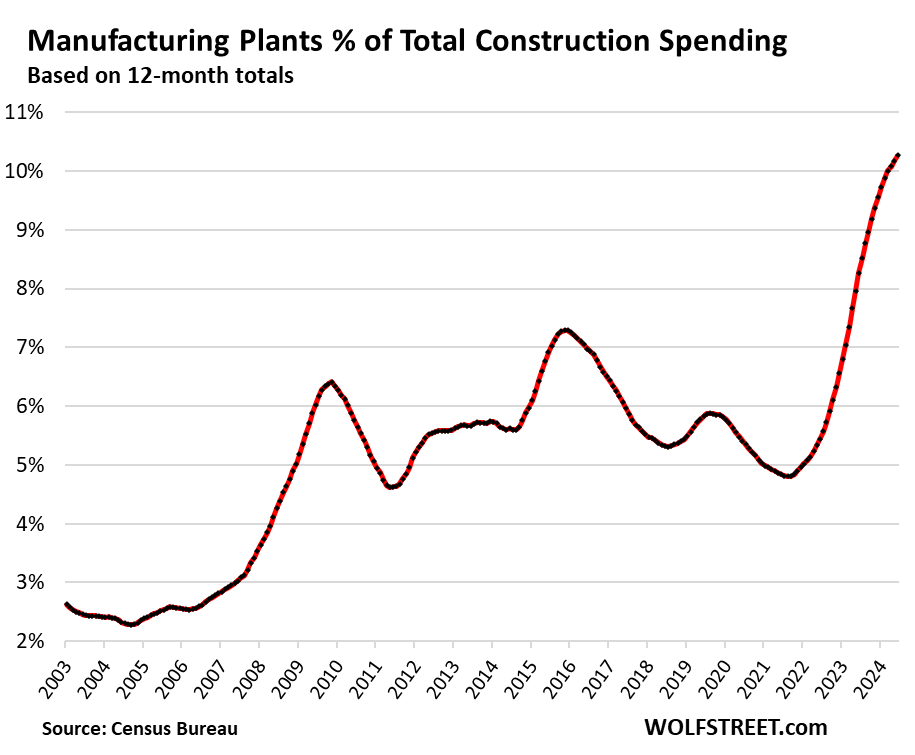

Construction spending on manufacturing facilities now accounts for over 10% of total construction spending in the US, residential and non-residential, from single-family houses to roads and power plants.

It’s all based on the principle that industrial robots cost the same in the US and China, that manual labor is a much smaller cost component in modern automated manufacturing, and that transportation costs (which spiked during the pandemic) and loss of Intellectual Property (IP), which is a given in China, and other risks have to be added to cost equation.

In addition, the increasingly complicated and stressed relationship between the US and China has exposed for all to see that the reckless dependence by US companies on production in China is a fundamental risk, not only for the companies, but also for national security.

No one is going to build a factory in the US to make low-value products, such as T-shirts. It’s all focused on complicated high-value products, such as motor vehicles, chips, electrical and electronic products, heavy components and equipment, etc.

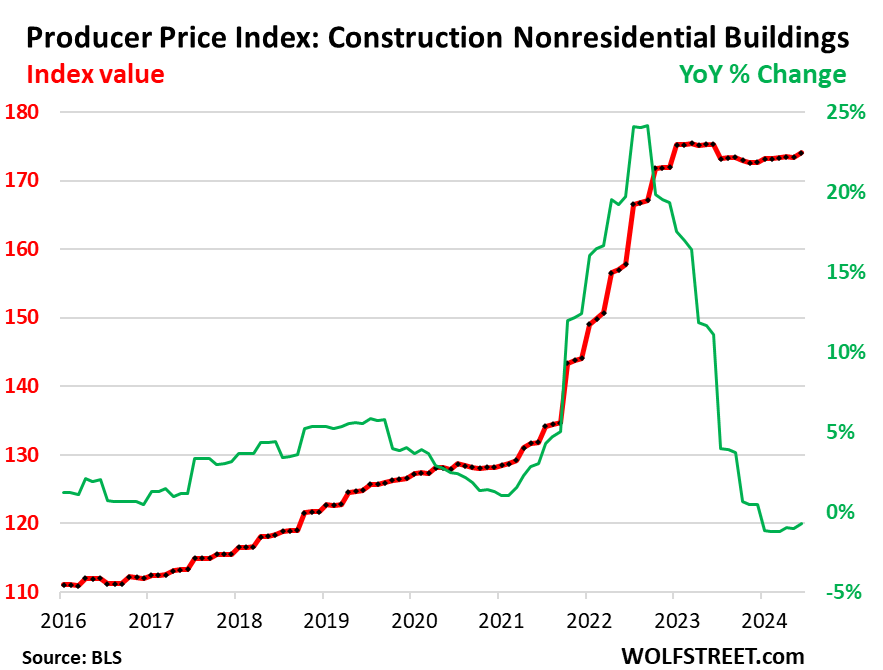

Inflation in Construction Has Abated

The Producer Price Index for construction costs of nonresidential buildings, after blowing out in mid-2021 through 2022, started plateauing in early 2023 and has remained roughly unchanged since then (red in the chart below).

On a year-over-year basis, the PPI for nonresidential construction has been flat to slightly negative since late 2023, after having spiked by as much as 24% in mid-2022 (green).