Yves here. This article describes some of the many concerns about geoengineering, above all the inability to properly model what some of the knock-on effects might be. A big reason that climate models have underestimated the pace of recent change is missing the severity of impact of some positive feedback loops, like methane releases from permafrost. It’s not hard to see why most would be leery of schemes that rest on reducing the amount of sunlight, when photosynthesis is essential for plants, which means agriculture and food production.

You’ll see below that unregulated and often non-transparent experiments are already underway. And what happens when Davos Man wannabe savior try to go big?

By Ramin Skibba (@raminskibba), an astrophysicist turned science writer and freelance journalist who is based in the Bay Area. He has written for WIRED, The Atlantic, Slate, Scientific American, and Nature, among other publications. Originally published at Undark

In April, in the Bay Area town of Alameda, scientists were making plans to block the sun. Not entirely or permanently, of course: Their experiment included a device designed to spray a sea-salt mist off the deck of a docked aircraft carrier. The light-reflecting aerosols, the scientists hoped, would hang in the air and temporarily cool things down in the area. It would have been the first outdoor test in the United States of such a machine, had the city council not shut it down before the experiment was concluded.

One of the goals of the experiment was to see if such an approach might eventually show a way to ease global warming. In a statement to the media on June 5, the researchers — a team from the University of Washington that runs the Coastal Atmospheric Aerosol Research and Engagement program — said the “very small quantities” of mist were not designed to alter clouds or local weather. The City of Alameda, along with many of its residents, though, were unconvinced, raising concerns about possible public health risks and a lack of transparency. City officials declined an interview request, but at the city council meeting at which the proposal was unanimously rejected, one attendee noted: “The project proponents went to great lengths to avoid any public scrutiny of their project until they had already operationalized their scheme. This is the complete antithesis of transparent, fact-based, inclusive, and participatory decision making.”

The concept of using technology to change the world’s climate, or geoengineering, has been around for a couple of decades, although so far it has been limited to modeling and just a handful of small-scale outdoor experiments. Throughout that time, the idea has remained contentious among environmental groups and large swaths of the public. “I think the very well-founded anxiety about experiments like this is what they will lead to next and next and next,” said Katharine Ricke, a climate scientist and geoengineering researcher at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography and the School of Global Policy & Strategy at the University of California San Diego.

In the best-case scenarios, successful geoengineering experiments could put a pause on or slow down the warming of Earth’s climate, buying time for decarbonization and perhaps saving lives. But other possibilities loom too: for example, that a large-scale experiment could trigger droughts in India, crop failures, and heavy rainstorms in areas that are wholly unprepared.

Indeed, skeptics sometimes associate geoengineering with supervillain behavior, like a famous episode of The Simpsons in which the robber baron Mr. Burns blocks the sun. They warn that outdoor experiments could set humanity down a slippery slope, allowing powerful billionaires or individual countries to unleash hazardous technologies without input or agreement from the public more broadly, all of whom would be affected.

Such an approach could also distract people from expanding decarbonization efforts. “Geoengineering doesn’t tackle the root causes of climate change; it’s arranged to counter some of the impacts, but it involves intervening in Earth’s systems at an absolutely enormous scale,” said Mary Church, the geoengineering campaign manager for the Fossil Economy program at the Center for International Environmental Law.

But now that human-caused climate change has accelerated, and with devastating effects already underway around the world, what previously appeared to be a risky Hail Mary technofix has gained respectability. Some scientists, including Ricke, as well as some environmentalists, political officials, and business leaders now call for tests of geoengineering technologies that could one day be used in an ambitious, or perhaps desperate, attempt to artificially cool the planet. Such outdoor experiments, these proponents argue, could demonstrate a particular approach’s utility and finally assuage critics’ concerns. Talk of solar geoengineering has become so widespread that people on the fringe, like Robert F. Kennedy, Jr., Donald Trump’s pick to head the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, have even espoused the conspiracy theory that the government, or Bill Gates, is already funding such experiments, through airplanes’ “chemtrail” emissions (which have always been of water vapor, not secret chemicals).

The stakes are high. Climate change is already changing nearly every realm of life across the planet, driving searches for all conceivable solutions, including ones that look risky. If people one day decide to proceed with some kind of geoengineering, they’ll first have to show that it’ll work, that it’ll be safe, and that the risks are bearable.

There’s no clear course on who gets to make such decisions, though. With no overarching governance on a technology that could — and will, if it works as intended — have global effects, current rules and regulations on smaller solar geoengineering experiments in the United States are limited to the local and state governments where such experiments may take place, which are ultimately led by officials with different perspectives and levels of expertise. (The lack of global governance has prompted government scientists in the U.S. and elsewhere to monitor the atmosphere for evidence of geoengineering experiments.)

And in that regulatory vacuum, all sorts of political questions arise, said Frank Biermann, a researcher of global sustainability governance at Utrecht University. Who will own the technology? Who decides how it will be used? What should be done if someone like Elon Musk, Donald Trump, or Vladimir Putin deploys it on their own? “All these questions, scientists have not considered them,” he said. “They just think, ‘this is a cool idea.’”

Some researchers, Biermann argued, have fallen prey to something he calls “the ‘Captain Kirk fallacy’”: The idea that super smart people, like those in a spaceship cockpit in the series Star Trek, just have to press a few buttons to solve all problems.

Modern geoengineering schemes date back to the early 2000s, when scientists first suggested an unprecedented experiment: If they dumped iron filings in the ocean, the material could spark vast phytoplankton blooms that would in turn draw in carbon dioxide from the atmosphere. Afterwards, the algae would eventually die and sink to the ocean floor, the theory suggested, taking the carbon down, too.

Such an experiment isn’t without risk. When agricultural run-off enters the ocean, for instance, pesticides and artificial fertilizers have caused toxic algae blooms, posing problems for fisheries and public health. Still, in 2004, a team led by oceanographer Victor Smetacek at Germany’s Alfred Wegener Institute tested the concept with several tons of iron sulfate in an iron-poor region near Antarctica, which indeed produced a phytoplankton bloom that began sinking a week later. Such activities were subsequently restricted by an updated version of an international accord called the London Convention and Protocol, which forbids polluting oceans with wastes, including dumping iron nutrients, except for “legitimate scientific research.” Then in 2012, rogue businessman Russ George took a ship off the Pacific coast of British Columbia and dumped some 100 tons of iron sulfate into the water. Critics debated whether George’s project violated international law, and no researcher has pursued iron fertilization since.

Other, more speculative geoengineering ideas have been developed by researchers over the years, too. For instance, astronomers have proposed strategies that would be deployed in space and partially block the Earth from the sun, such as launching a giant, tethered shield shade between them, or periodically blasting moon dust into space. It’s an out-there idea, said Benjamin Bromley, a University of Utah astrophysicist who led a study on the possibilities for lunar dust and who concedes he’s ventured out of his lane. “But it’s absolutely worth exploring. We would hate to miss an extraordinary opportunity to buy us some more time, should the critical measures we take on Earth fail.”

Although space-based geoengineering avoids some risks of taking action within Earth’s atmosphere, either of these projects would be mind-bogglingly, and perhaps prohibitively, costly. István Szapudi, a University of Hawaii astrophysicist who proposed the sun shield, acknowledges the huge costs, even if launch costs continue dropping, but describes it as a matter of priorities. “If we spent 10 percent of what people spend on weapons in a year, for a few decades then we could easily do this project. How cool it would be, instead of spending on stuff that destroys the Earth, we spend it on something that would make the Earth more livable,” he said. In any case, if the climate crisis becomes more dire, policymakers and investors might begin taking seriously ideas that today seem outlandish.

Today, most researchers are more sanguine about more down-to-earth approaches to limiting incoming sunlight: solar geoengineering or solar radiation management. Here, researchers would reflect some sunlight away from the ground for a period of time, temporarily cooling the planet for however many decades it takes to cut carbon levels. Two of the main approaches involve spraying particles with the goal of reflecting sunlight. The first, called stratospheric aerosol injection, involves high-altitude airplanes or tethered balloons releasing millions of tons of small reflective particles, like sulfuric acid, into the stratosphere, which is around seven to 30 miles above the ground. The second, marine cloud brightening, involves misting the lower atmosphere with sea-salt aerosols to make clouds more reflective over particular parts of the ocean — the same approach that the University of Washington researchers aimed for in Alameda.

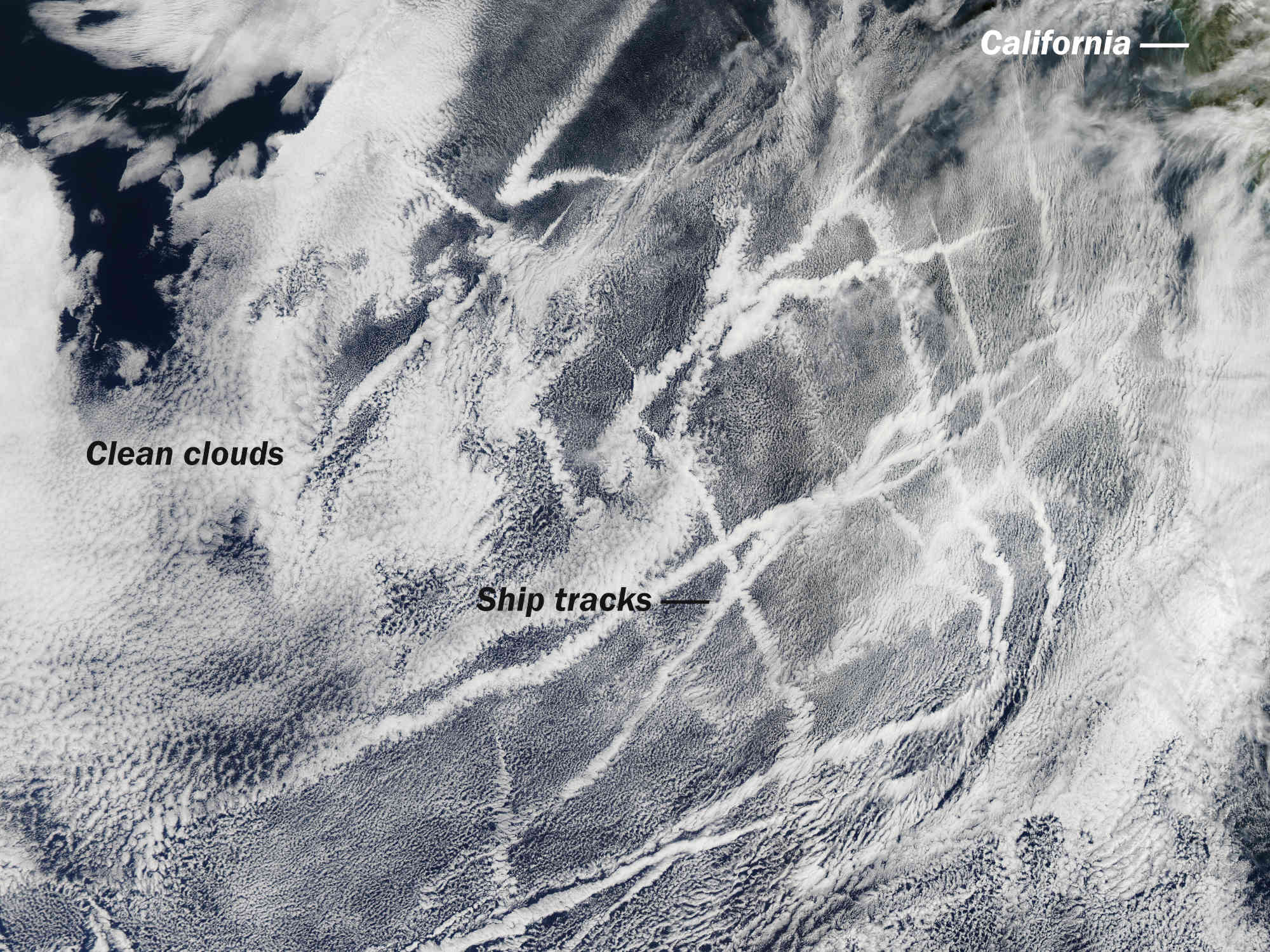

Both have analogs in the real world, Ricke said, allowing scientists to estimate the impacts of the techniques. Stratospheric aerosol injection, for instance, is similar to the large amounts of dust and ash thrown up by large volcanoes, such as Mount Pinatubo in the Philippines, whose 1991 eruption single-handedly cooled the planet by half a degree Celsius for more than a year. Scientists can look at records of such examples to see how much the planet cooled and for how long. Scientists also have learned from measurements of sulfur particles emitted by ships’ exhaust, which create wispy, reflective, contrail-like clouds, similar to what marine cloud brightening could achieve. “Those are the two methods right now that it seems like could potentially be economically and technically feasible and could reduce risks if they work,” she said. (Some researchers consider these geoengineering concepts distinct from carbon dioxide removal projects intended to achieve negative emissions. So far, these carbon removal efforts have been smaller in scale, are independent of one another, and would take longer to take effect, but if they expand rapidly, they too come with environmental impacts and drawbacks.)

Neither approach is without risk. “With stratospheric aerosol injection, we are more or less certain it could work, as in it could cool the planet substantially, but with many side effects,” said Peter Irvine, a geoengineering and climate researcher at University College London. He assesses cloud brightening similarly, but with more uncertainties about how it could be deployed and about the precise particles needed.

Among those side effects: the aerosols could change rainfall patterns, and delay the recovery of the ozone layer. Those drawbacks could be long-lasting, too. If countries or companies commit to solar geoengineering, they’d need to continue it for however many decades or centuries it takes to address the root causes of global warming — the burning of fossil fuels — which could be costly in terms of resources and tradeoffs.

“Even if this is a bad idea, we should know more to be sure,” Irvine said.

But scientists’ attempts to conduct real-world experiments have foundered on public and policymakers’ concerns. The researchers who led the failed attempt to experiment in Alameda declined Undark’s interview requests. In a statement sent by email, the team described providing “extensive data” on the proposed experiment to spray sea-salt particles into the air, adding that “all of the experts engaged affirmed the safety of the sea-salt spray involved in the studies.”

Other geoengineering experts closely watched the outcome. In some sense, what happened in Alameda may have blown up in part because the researchers’ leadership team may have conducted their proposal process in “a very closed, secretive way,” said David Keith, head of the Climate Systems Engineering initiative at the University of Chicago.

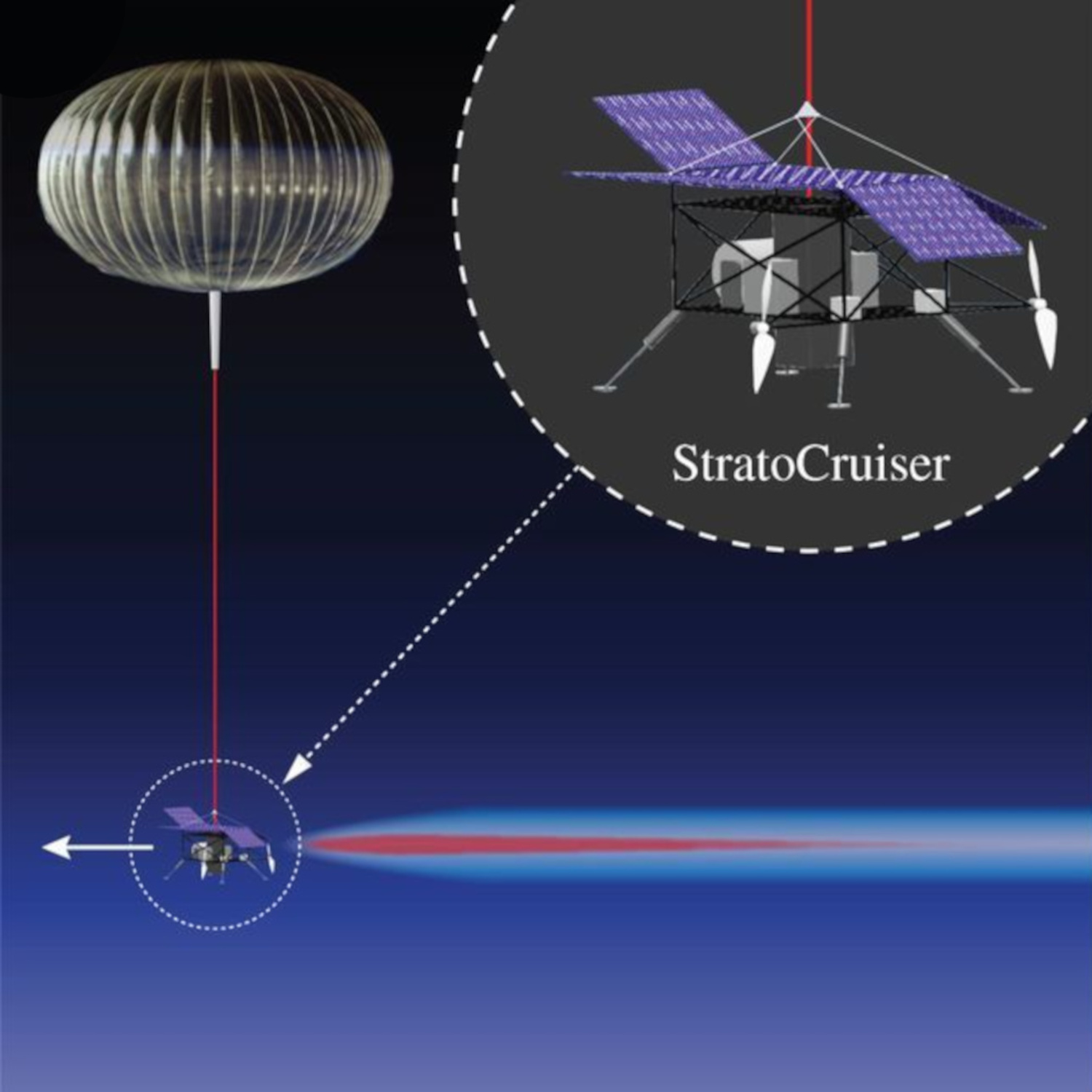

That approach may have been in direct reaction to Keith’s own past failed attempts at gaining approval for a geoengineering experiment, he said, which was similarly thwarted by public concerns and local authorities’ skepticism. In the 2010s, when Keith was at Harvard University, he and a colleague, climate scientist Frank Keutsch, proposed lofting high-altitude balloons fitted with airboat propellers that would release between 100 grams to a couple kilos’ worth of mineral dust, like calcium carbonate or sulfuric acid. The researchers planned to then measure and observe how the tiny particles disperse and reflect sunlight. The project, called the Stratospheric Controlled Perturbation Experiment, or SCoPEx, was necessary, the team argued, because it wasn’t clear whether existing computer simulations would truly align with a real-world scenario.

But they struggled in their efforts to find a location to host the test. Keutsch and Keith first sought to deploy the balloons in Tucson, Arizona, but partly because of logistical and scheduling challenges while working with balloon operators during the pandemic, they shifted their sights to other possible sites. In December 2020, the team announced plans to test their platform in the Lapland region of northern Sweden, where they partnered with the Swedish Space Corporation. But they encountered multiple critics, including Indigenous tribes and environmental groups, such as the Saami Council, the Swedish Society for Nature Conservation, and Swedish climate activist Greta Thunberg. The Saami Council objected to a lack of consultation and to an approach that doesn’t address the carbon emissions driving climate change, while environmentalist critics saw the experiment as a step heading down a slippery slope of full deployment. An advisory council recommended holding discussions with the public before launching any flights, and when the council did not recommend proceeding, the Swedish space agency called it off, forcing them to cancel their plans. In March 2024, according to a university statement, Keutsch “announced that he is no longer pursuing the experiment.”

The failure has prompted postmortems by the scientists. “I think we tried to be too open, we tried to always talk to journalists and tell them, ‘This is what we’re thinking of doing’ and so on,” Keith said. “And it ended up blowing up in the press and was way over-reported, and I think that’s part of what killed it.”

Despite their scuppered plans, Keith believes public opinion, and the views of scientists and political leaders, are changing, with more people than before in favor of researching, experimenting, or deploying geoengineering technologies. “The fraction of scientists who support research is probably quite high,” he said. “More than it was a decade ago.”

While geoengineering originally was anathema to the scientific and environmental communities, that landscape has begun to shift in recent years. Ricke herself has championed solar geoengineering research, such as in a talk at South by Southwest last year, where she and other panelists made the case that while geoengineering is still contentious today, depending on the results of that research, it could become a viable climate solution in combination with emissions reductions and other strategies.

“Shunning this research is riskier than studying it,” Ricke wrote in a 2023 piece for Nature magazine. Most knowledge about solar geoengineering so far has come from computer modeling, she continued, but even the most realistic models could miss real-world complexities. Researchers’ models also don’t reflect the geopolitical reality that there likely won’t be global cooperation on geoengineering, and uncoordinated, regional projects could arise instead, she wrote. But the impacts of such a scenario aren’t well understood.

Her perspective isn’t a fringe one: Such research now enjoys the imprimatur of the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, which published reports in 2015 and 2021, and the American Geophysical Union, which includes leading U.S.-based climate scientists. The National Academies committee recommended continuing to investigate solar geoengineering, including the possible unintended consequences and geopolitical challenges involved, said Chris Field, a climate scientist at Stanford University’s Woods Institute for the Environment and chair of the latter report. He acknowledged that ongoing research may show that the technology won’t work as intended, and in that case, he said, “we should then refocus attention on the things that will work, including cutting greenhouse gas emissions.”

Even if solar geoengineering does work as planned and reduces global warming, he added, some harmful climate impacts, like ocean acidification, would be unaffected by such interventions — another reason to prioritize reducing emissions.

Other influential geoengineering backers include billionaire philanthropist Bill Gates, who has been supporting and investing in research projects, including SCoPEx, since the 2000s. Some members of U.S. Congress have expressed support as well, evidenced by the push to mandate clear research plans, and Quadrature Climate Foundation, the philanthropic arm of a London-based hedge fund, has become a major investor. Still, 75 percent of Americans are somewhat or very concerned about using solar geoengineering, a 2021 Pew survey found, though only a minority are familiar with the technology. There’s some evidence that people who are more exposed to information about climate change may support geoengineering more, according to another study, which was co-authored by Irvine. Public opinion research shows that many people share the same concerns that environmental and Indigenous groups have, though overall there’s not much public awareness of geoengineering yet.

Some of the concern stems from what climate researchers call the “moral hazard” problem — the possibility of humanity geoengineering its way out of climate impacts could discourage decarbonization efforts. “I think the greatest opposition comes from those closest to climate change, because I think it’s viewed as the wrong way to deal with climate change,” Irvine said. “There’s a concern that it’ll distract from the real solutions, which are of course cutting emissions.”

Despite the growing support for geoengineering research, the scientific community is no monolith, and plenty of other researchers, like Utrecht University’s Biermann, have grave concerns. He fears that if expensive, high-profile experiments come to fruition, large-scale deployment eventually will become unavoidable, for better or worse. In 2022, he and others began calling for a non-use agreement on solar geoengineering — that is, a moratorium. Their open letterhas drawn more than 530 signatories from 67 countries so far, including prominent scientists like Michael E. Mann of the University of Pennsylvania; Dirk Messner, head of the German Environment Agency; Indian writer Amitav Ghosh; and Åsa Persson, research director of the Stockholm Environment Institute.And while there is increasing support for geoengineering in the U.S. among researchers and some policy makers and environmental groups, Biermann points out that there is not much support in European countries and the Global South, especially African nations and small island states. Some 2,000 nongovernmental groups have endorsed the non-use agreement as well, Biermann noted, in an open letter that reads in part: “there is a risk that a few powerful countries would engage in solar geoengineering unilaterally or in small coalitions even when a majority of countries oppose such deployment.”

Biermann views the risks and prospects for geoengineering differently compared to scientists like Ricke and Keith. “Geoengineers are pessimistic regarding climate policy, and they’re optimistic regarding having 1,000 stratospheric aircraft that aren’t invented yet to fly around the stratosphere for 100 years, 24-7, without any geopolitical turmoil,” he said. He and his colleagues don’t want to regulate geoengineering modeling and computer simulations — he supports academic freedom and doesn’t want anyone policing scientists’ labs — but he draws the line at outdoor experiments and calls for bans on public funding for the development of such technologies.

Once people invest in the technology in earnest, whether it’s balloons, drones, or aircraft, there will be considerable momentum toward actually using it, he argues. Moreover, in his perspective, to really understand how geoengineering technology might work or not, one would need planet-wide experiments, but such projects would be little different than large-scale deployment. In other words, the only way to find out if the technology is safe is for someone to take a gamble with planetary stakes.

As in the scientific community, geoengineering has divided environmental groups. Some, like Friends of the Earth and Greenpeace, reject geoengineering in any form, while the Union of Concerned Scientists opposes it because of the “environmental, ethical and geopolitical risks, challenges and uncertainties.” The U.S. nonprofit Center for International Environmental Law opposes the technology for other reasons, including possible catastrophic consequences and the potential for distraction from other climate solutions. “You can’t test for the impact of deploying geoengineering technologies at scale without deploying them at scale. That is the problem,” said Church, the group’s geoengineering campaign manager, echoing arguments by Biermann and moratorium proponents.

A decade ago, the Environmental Defense Fund wasn’t exactly gung-ho about solar geoengineering. Now, however, among the major environmental organizations, they stand alone as a clear booster, supporting small-scale field research. Eventually, the EDF will begin to sponsor research projects, which could involve both stratospheric aerosols and cloud brightening, to gain “decision-relevant data” and learn more about “potential downstream impacts on agriculture and air quality,” said Brian Buma, a senior climate scientist at the organization. The group’s position hasn’t really shifted, he argues. “It’s not a solution; it’s potentially a tool to stave off some of the worst effects, assuming a good mitigation pathway. We call it ‘peak-shaving,’” he said, but it’s not a substitute for reducing emissions.

Could a maverick billionaire or rogue state go it alone and unleash a geoengineering project, without any official approval or oversight? Currently, while some national and international laws prohibit large scale experiments, there are exemptions for small-scale geoengineering projects, so there’s not much to stop someone or some organization from taking such actions, particularly in the United States. Only a few companies are actively involved in geoengineering research and development at this time, however, and they don’t yet add up to an advanced geoengineering industry.

Over the past few years, geoengineering research and hype has spawned investment in new startups attempting to capitalize on growing interest and on impatience with sluggish climate policies. For example, in 2022, Andrew Song, an entrepreneur, co-founded Make Sunsets, a startup backed by Silicon Valley-based venture capital firms like Boost VC and Draper Associates. The company has focused its efforts on developing balloons releasing stratospheric aerosols, mainly sulfur dioxide. To make money, the company sells cooling credits, at a rate of $1 per metric ton of carbon dioxide emissions they claim to offset, with the idea that corporations buying them can do so to reach their net-zero emissions targets.

Song lamented the fate of Keith’s ScoPEx, the canceled stratospheric balloon research project. “We thought, if the top scientist in the world, funded by Bill Gates, gets $20 million dollars, can’t even launch a single balloon with some instrumentation and a little bit of calcium carbonate, that’s not the right path,” Song said. “He tried to get permission from everybody and then gets blocked by a bunch of reindeer herders.” That’s when he and fellow cofounder Luke Iseman, formerly at Y Combinator, a group that helps to launch startup companies, decided to start small, landing on their strategy of cheaper balloons, of which they’ve launched 90 so far, according to their website. They have yet to run into any regulatory issues in California or Mexico, he said. Their balloons reportedly flew over the airspace of multiple tribes in California, a potential sticking point, but Song told Undark that the company has altered its flight paths to avoid these areas, following that critical news coverage.

Song expressed confidence about the future of stratospheric aerosols, which he refers to as “sunscreen for Earth” or, more abstractly, “Ozempic for climate change.” He’s said that he’s skeptical that governments will come together and agree on climate policy or on deploying geoengineering. “It’s going to be a unilateral decision. If it’s not us, it’s going to be India,” he said. He does worry that, in one geoengineering scenario, the strength of the Indian monsoon season will decrease, threatening millions with drought and famine, a nightmare scenario depicted in sci-fi author Neal Stephenson’s novel “Termination Shock,” which Iseman has read. But the alternative of living in a world with 4 degrees C warming would be far worse, he argued.

Song also sees one of Make Sunsets’ roles as providing much-needed field data for scientists like Keith. “We obviously want to collaborate, but we’re seen as the pariahs right now, we’re seen as the bogeymen,” Song said. Keith, for his part, sees Make Sunsets more as a “theater piece” than as a startup. But stunts can be effective at changing minds, he added.

Meanwhile, a secretive Israeli-U.S. startup called Stardust Solutions is trying to use its own particular brand of aerosol technology for solar geoengineering. They’re conducting their own research and development and planning a series of experiments, and they see their role as one that involves working with governments and researchers. “Decision-making regarding whether, when, and how to deploy solutions like SRM should only be taken by governments,” said CEO Yanai Yedvab, a former deputy chief scientist at the Israel Atomic Energy Commission, in a written statement to Undark. Stardust acknowledges concerns about potential harms to the ozone layer and effects on climate patterns, he continued, and they are attempting to develop a specialized aerosol particle and a deployment mechanism to mitigate such effects.

Ricke finds Stardust’s approach a concerning one. “They’re developing proprietary materials and technology and have taken a lot of investor dollars, and the only way that they’ll ever make that money back is if they convince someone to actually do solar geoengineering, which is a pretty dangerous situation to be in,” she said.

Few rules are in place, if Make Sunsets, Stardust, or someone else desires to push ahead with solar geoengineering. At the international level, the Convention on Biological Diversity, which has been ratified by nearly 200 countries but not the U.S., implemented a geoengineering moratorium, allowing some small-scale scientific research. But what’s allowed is open to interpretation, Field said. In the U.S., a company needs only to file a brief form with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration 10 days before releasing aerosols in the stratosphere. The primary relevant oversight from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency is through the Clean Air Act, which does regulate sulfur dioxide as a pollutant and as a contributor to acid rain. Other federal agencies are continuing to assess geoengineering research. According to a White House Office of Science and Technology report last year, “The potential risks and benefits to human health and well-being associated with scenarios involving the use of SRM need to be considered,” as well as the risks and benefits of unfettered climate change. The report did not initiate a government research program, though it opened the door to that possibility, and it did not propose specific new regulations, but it stated that any research program must have “transparency, oversight, safety, public consultation, international cooperation, and periodic review.”

For Ricke, setting up international rules should be a top priority. “Right now the absence of any norms or standards is leading to a situation where responsible research is being suppressed.” Instead, she said, rogue actors, including researchers, are in the driver’s seat. And they’re testing the few boundaries that exist, making it hard to produce findings and information that scientists — or anyone — can really trust.