PHOENIX — The first thing Carmen Jones noticed was the FBI sniper on the roof of the Fort McDowell Casino following her as she walked around the building with her 10-month-old son in her arms. Nearby, more FBI agents in heavy flak jackets, some toting assault rifles, stood guard, sweltering in the 90-degree heat.

Jones, a tribal member of the Fort McDowell Yavapai Nation, which owned and operated the casino, had rushed to the casino from her home after getting a call from Yavapai tribal elder Ella Doka. The older woman had driven a friend to work around 6 a.m. on May 12, 1992, when she saw the tribes’ slot machines being loaded into moving vans.

Soon, Jones and her child were joined by other women from the tribe and her uncle, Gilbert Jones, a member of the Fort McDowell Tribal Council. They parked their cars in front of the moving vans and kept watch while others went to call for more help.

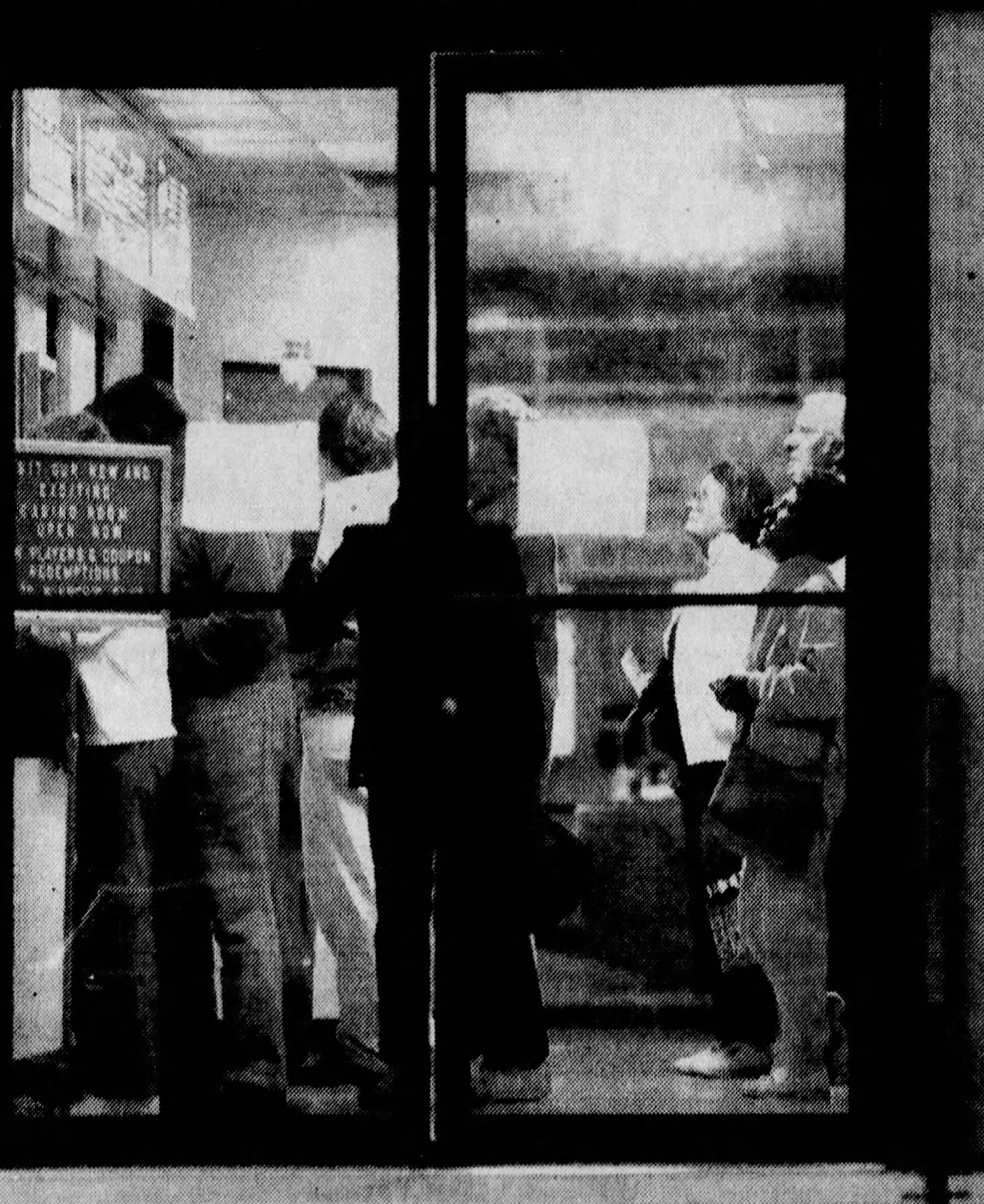

TOP: The 28,000-square-foot bingo hall on the Fort McDowell Mohave-Apache Indian Community is crowded with about 1,000 people. (Published August 11, 1986) BOTTOM: The Fort McDowell Casino pictured after FBI agents took 300 gambling machines. (Published May 13, 1992) TOP: The 28,000-square-foot bingo hall on the Fort McDowell Mohave-Apache Indian Community is crowded with about 1,000 people. (Published August 11, 1986) BOTTOM: The Fort McDowell Casino pictured after FBI agents took 300 gambling machines. (Published May 13, 1992) LEFT: The 28,000-square-foot bingo hall on the Fort McDowell Mohave-Apache Indian Community is crowded with about 1,000 people. (Published August 11, 1986) RIGHT: The Fort McDowell Casino pictured after FBI agents took 300 gambling machines. (Published May 13, 1992) FILE PHOTO, THE REPUBLIC

More Yavapai people rushed to the scene, surrounding the parking lot and the perimeter of the casino, blocking the trucks from coming or going in what was rapidly becoming a stand for tribal rights. Within two hours, the Fort McDowell tribal sand and gravel company sent its huge earthmovers across the Verde River to join the blockade. People yelled at the agents to put the machines back and leave them alone to run their business.

Over the next few hours, even more Native people and their allies joined the blockade. They stood guard over vans adorned with the Mayflower moving company logo. They blocked the government’s vehicles, preventing the moving vans and the FBI from leaving with more than 300 gaming machines.

At noon, Arizona Gov. Fife Symington learned of the showdown and flew the 30 miles to the small reservation to meet with Fort McDowell President Clinton Pattea to defuse the situation. After negotiating a cooling-off period, the tribe continued to protest with powwows and prayer rallies, as neighbors supplied food and water to those involved. Eventually, the tribe won a compact with the state to engage in gaming.

For many Native people, the raid and subsequent 10-day standoff represented a call to defend their land and government from being overrun by the state. The showdown between the tiny Arizona tribe and the U.S. government was a turning point in the history of Indian Country and tribal sovereignty, paving the way for the growth of Indian gaming as an economic driver and pulling many tribes out of poverty.

“[The standoff] is such an incredible event and a touchstone for tribal sovereignty,” said Victor Rocha, a member of the Pechanga Band of Luiseno Indians and a nationally known tribal gaming expert. “Even to this day, I go back and I watch the videos.”

DO NOT PUBLISH How a tribal protest in 1992 changed Indian gaming

The small Fort McDowell tribe held off armed federal agents through a peaceful resistance and won a victory for tribal sovereignty.

Joel Angel Juarez, Arizona Republic

The Fort McDowell Yavapai Nation, known in 1992 as the Fort McDowell Mohave-Apache Tribe, is about 30 miles east of Phoenix.

The small tribe was mired in poverty. The roads through the 40-square-mile reservation were unpaved until the 1970s. The highway to Phoenix was a narrow two-lane road. Tribal kids rode the bus more than 10 miles to the nearest school until the mid-1980s when schools opened in the newly established town of Fountain Hills, now the tribe’s next-door neighbor.

Bernadine Burnette, 66, like others of her generation, grew up in homes with dirt floors and without running water or electricity. Burnette, the current tribal president, said the tribe had a small clubhouse where kids could watch a black and white television and buy candy for a nickel.

Jobs were scarce so far from Phoenix and many tribal members were forced to ride the bus to work in Phoenix or other cities in the region. When the tribe leased some of its water to Phoenix, some tribal members were able to get jobs at the water treatment plant at the southern end of the reservation.

Tribal leaders were determined to provide a better life for the 400 community members than what government programs had supported after many decades of federal underfunding. In addition to leasing some of its water allotment, the tribe grew alfalfa and other crops and ran a sand-and-gravel operation to generate revenue.

And in 1984, Fort McDowell opened a bingo hall.

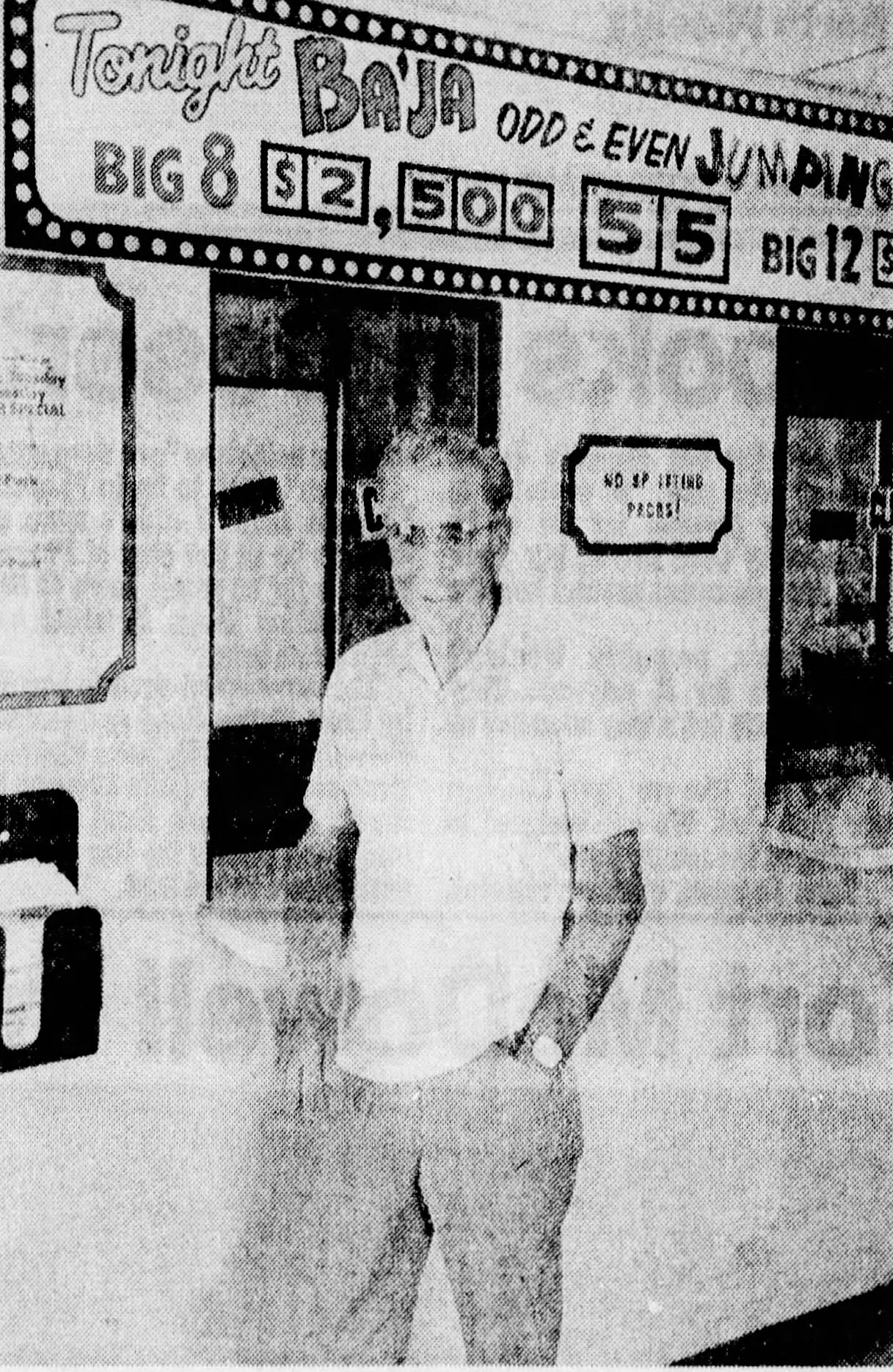

TOP: Customers line up at the entrance to a bingo hall at the Fort McDowell Mohave-Apache Indian Community. (Published February 18, 1990) Howard Murray, general manager of the bingo operation, says the top prize he’s ever paid is $15,000, but such high payouts are rare. (Published August 11, 1986) TOP: Customers line up at the entrance to a bingo hall at the Fort McDowell Mohave-Apache Indian Community. (Published February 18, 1990) Howard Murray, general manager of the bingo operation, says the top prize he’s ever paid is $15,000, but such high payouts are rare. (Published August 11, 1986) LEFT: Customers line up at the entrance to a bingo hall at the Fort McDowell Mohave-Apache Indian Community. (Published February 18, 1990) Howard Murray, general manager of the bingo operation, says the top prize he’s ever paid is $15,000, but such high payouts are rare. (Published August 11, 1986) FILE PHOTO, THE REPUBLIC

Many tribes found themselves on reservations that lacked sufficient arable land, water or other resources. Others, including Fort McDowell, were far from urban areas, which limited their ability to pursue significant economic development.

Many Native American leaders began turning to high-stakes bingo in the 1970s as a way to bolster their economies and provide needed services for their citizens. Other tribes added slot machines.

Two key Supreme Court decisions paved the way for tribal gaming. In 1976, the court ruled that states could not assess personal taxes on property owned by Native people on tribal land. And in the 1987 case California v. Cabazon Band of Mission Indians, the high court ruled that gambling in tribal lands could not be regulated by states.

The passage of the Indian Gaming Regulatory Act in 1988 gave the small tribe and many others in the United States the means to bolster resources needed for infrastructure, social services and jobs.

The law, which was drafted by Sen. John McCain of Arizona, stipulated that tribal gaming would be allowed only in states that already sanctioned some sort of gambling, such as a state lottery, card rooms, horse racing or casinos.

Adding slot machines and video poker to the bingo operations in 1992 greatly increased Fort McDowell’s bottom line.

At the time of the raid, the tribe was earning $3.4 million a month from the machines, which provided revenues for new homes, health care, jobs, elder services and other community needs that had long been lacking.

Symington, fearful that the state would become a gambling mecca, refused to create compacts with tribes as required by the gaming act. Four tribes sued the state, while the others, including Fort McDowell, insisted that it was their sovereign right to offer gaming on their tribal lands. Since the state already regulated dog and horse betting, the tribes felt it would have to abide by the federal law and create gaming compacts with them.

Symington asked U.S. Attorney Linda Akers to resolve the situation. Akers in turn warned the tribes that they risked seizure of the machines if they didn’t remove them.

But the federal and state governments failed to reckon with the indomitable spirit of the Yavapai people who had already fought – and won – several battles dating from the late 19th century. The tribe fought for its reservation, for the right of Native Americans to vote, for the right to lease part of its water settlement and to prevent its lands from being drowned beneath a reservoir.

Around noon on May 12, Mark Flatten, a reporter for the East Valley Tribune, phoned Doug Cole, Symington’s deputy chief of staff.

“I called to get a comment on what was happening out at Fort McDowell,” Flatten said.

That morning, Flatten heard about a commotion out at the Yavapai reservation. “I figured I’d drive out there and see what was going on,” he said.

Flatten saw what he described as a “spontaneous uprising” of Native people with personal vehicles and earthmoving equipment who were blocking the Mayflower moving vans and the FBI’s vehicles from leaving.

Cole was used to getting calls from reporters, but this one set off alarms. He popped into Symington’s office and said, “Governor, we have a problem.”

FILE PHOTO, THE REPUBLIC

That’s the first Symington said he knew of the situation.

“We knew nothing about the raid or the activity,” Symington told The Arizona Republic, part of the USA TODAY Network.

Cole told the governor that tribal members had banded together, barricaded the FBI inside the perimeter of the casino parking lot and wouldn’t let them leave.

“I decided that it was important that I go out there even though I had no real authority because it was on federal land,” Symington said.

The federal government holds land in trust for tribes, which govern the land as sovereign tribal nations.

“It sounded like they were close to violence and I didn’t want that kind of thing on my watch,” Symington said.

Symington took an Arizona Department of Public Safety helicopter to Fort McDowell and on landing saw the Mayflower vans holding the gaming machines.

“How ironic that was,” he said. “Early ships landing on North America, invading Native lands.”

Symington said he thought that use of the trucks with the logo of the Pilgrims’ ship could have been an “in your face” move on the part of the U.S. government.

The governor and the Fort McDowell president met in private and agreed on a 10-day cooling-off period to allow for negotiations.

Pattea was a seasoned veteran of skirmishes with federal and state officials. He was a Tribal Council member during the tribe’s struggle in the 1970s to prevent a dam from drowning their reservation and effectively breaking up the community.

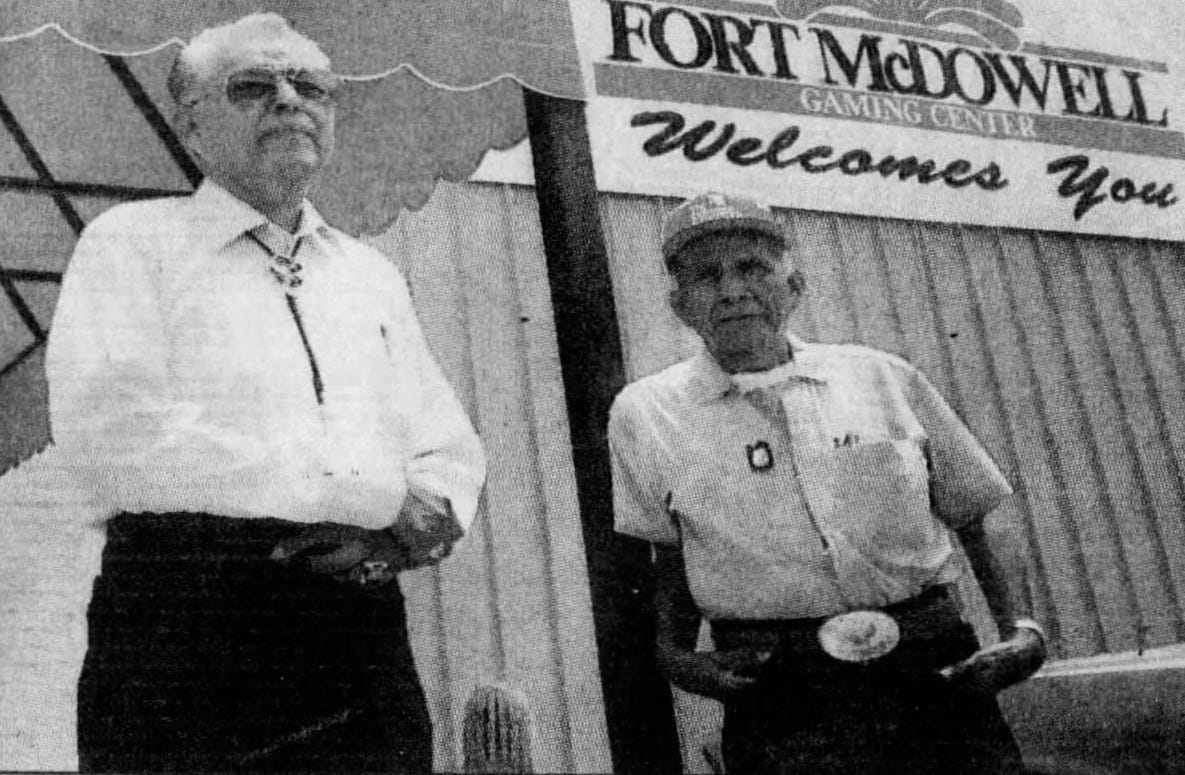

Tribal president Clinton Pattea (left) and Vice President Gilbert Jones work together to protect the interests of the Fort McDowell Indian Community. (Published June 8, 1992) The Republic

State and federal officials wanted to build the dam at the confluence of the Verde and Salt rivers, but tribal members opposed the idea and forced Arizona and the federal government to withdraw the proposal and redraw parts of the plan that established the Central Arizona Project. Fort McDowell now celebrates that decision each November with Orme Dam Victory Days.

Pattea, who held a bachelor’s degree in business and worked in banking, was first elected to the Tribal Council in 1959 and served as the executive secretary of the Arizona Commission of Indian Affairs from the mid-1970s through the late 1980s. He had retired from state service to serve on the Tribal Council full time.

Flatten said Symington’s swift move to meet with Pattea and negotiate the cooling-off period defused what could have been a tragic outcome.

“There were a lot of big issues playing out there on that small patch of ground,” Flatten said. “There were federal issues, state issues and tribal issues that came together on that tribal land.”

On the day armed FBI agents stormed the casino building along Arizona State Route 89, known to locals as the Beeline Highway, the Fort McDowell Gaming Center was about 50,000 square feet and offered bingo, slot machines and video poker machines to patrons eager to try their luck without taking the long drive to Las Vegas.

The feds sought out those machines because they said the tribe had no legal right to operate them.

“There were like 150 FBI agents and officers with their blue jackets with ‘FBI’ on the backs,” said Roddy Pilcher, the casino’s cash operations manager at the time, who was working inside.

Pilcher swiftly directed employees to empty out slot machines and hide the cash.

“Don’t count it, don’t write anything down, just get the money out and hide it,” he told the workers.

Within minutes, FBI agents served him and other managers with warrants to search the casino’s files for ownership papers. The agents started to load the tribe’s 349 gaming machines into Mayflower moving vans parked outside.

Pilcher and other tribal members set up phone trees to notify the tribe about the raid. Soon, people began arriving.

Pilcher said what was most hurtful about the experience were the guns pointed at him and other casino workers, both Native and non-Native.

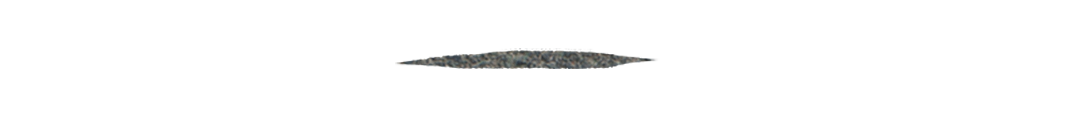

TOP: Benjamin Anton (foreground) and his mother, Denise Alley, listen during a powwow circle near the gaming center at the Fort McDowell Mohave-Apache Indian Community. (Published May 17, 1992) BOTTOM: Wendy Thomas and her 11-month-old son, Spear, join protestors on a march from the Fort McDowell Indian Community gambling hall, May 20, 1992. TOP: Benjamin Anton (foreground) and his mother, Denise Alley, listen during a powwow circle near the gaming center at the Fort McDowell Mohave-Apache Indian Community. (Published May 17, 1992) BOTTOM: Wendy Thomas and her 11-month-old son, Spear, join protestors on a march from the Fort McDowell Indian Community gambling hall, May 20, 1992. LEFT: Benjamin Anton (foreground) and his mother, Denise Alley, listen during a powwow circle near the gaming center at the Fort McDowell Mohave-Apache Indian Community. (Published May 17, 1992) RIGHT: Wendy Thomas and her 11-month-old son, Spear, join protestors on a march from the Fort McDowell Indian Community gambling hall, May 20, 1992. SCOTT TROYANOS/THE ASSOCIATED PRESS; SUZANNE STARR, THE REPUBLIC

Gerald Doka, now a member of the Tribal Council, was at his job at the tribal nursery when his boss drove up and told him trucks were backed up to the casino with FBI agents guarding them. Doka and four other tribal members drove down to see what was happening.

“We saw about six people standing there, five of which were women,” said Doka. “My mom, Ella Doka, was one of those ladies.”

Gerald Doka said someone came up with the idea to call people or drive to their homes. Within two hours, the crowd grew to several hundred tribal members as the FBI continued to load up machines.

“People were arguing with the FBI telling them to get off our land, this is our land,” he said. “This is the first time I had ever heard the word sovereignty come up.”

JOEL ANGEL JUAREZ/THE REPUBLIC

The tribal attorney explained to the crowd what the term meant. By that time, the media had arrived, with news helicopters, cameras and reporters.

Burnette, the future tribal president, was also on the phone. Although she worked at a federal agency at the time and could not take direct action, she could make phone calls.

“My daughter asked, ‘Mom, what do I do?’ I said, ‘You’ll get instructions.’ We all started conversing with each other.”

Burnette emphasized that even though she couldn’t be at the standoff, her heart, thoughts and prayers went to the community.

Tom Jones, the council member’s brother and father of Carmen Jones and a Vietnam War veteran who served in the Marines, was on duty as an equipment operator at the city water treatment plant.

“The tribal members here wanted to hang on to the machines and they wouldn’t let the machines out of the reservation,” said Tom Jones.

He said he got involved in the conflict because as a tribal member, he wanted to protect his tribal rights and sovereignty to have gaming machines if they wanted them. “If a state had gaming, then the tribe was entitled to gaming,” he said.

He rushed to the casino after his shift was over.

“We had a gathering in the evening, and the next night we had a powwow during the 10 days to cool off, and we had 10 days of powwows after that,” Tom Jones said. “A lot of tribal members from different tribes in New York, Oregon, Washington, New Mexico, and plus the 21 tribes here in Arizona, came. There were a lot of people there that came to help us show our resistance.”

Clissene Lewis (right) greets Ophelia Kill during a powwow in the Fort McDowell Indian Community. The Mayflower trucks in the background hold gaming equipment seized by the FBI. (Published May 14, 1992) Paul F. Gero/The Republic

Among them, a group of Mohawks on motorcycles arrived from New York to support the tribe’s stance.

People and nearby businesses brought food and water; one Fountain Hills restaurant sent sandwiches. Inside, the bingo hall continued operations.

Outside of the casino, a group of Yavapai men organized watchers at the southern end of the reservation to warn of any new incursions. Others prepared for battle.

Tom Jones said some of his nephews made Molotov cocktails in case the FBI decided to move the machines out before the 10-day period was up. In the end, cooler heads prevailed and the standoff remained peaceful.

“I went to our (Bureau of Indian Affairs) office and they were handing out bullets and helmets to the officers, who were also Native,” Tom Jones said. “I said, ‘We’re all tribal members, one tribe or another. We need to help each other.'”

He said he reminded them that they all had been subject to genocide and suppression and he felt their job was to protect Native people.

After the cooling-off period, Fort McDowell members held a march to the Arizona Capitol to raise awareness of their fight for tribal rights. A story in The Arizona Republic in June 1992 said then-Attorney General Grant Woods proposed allowing slot machines on tribal lands after the march.

TOP: Red Sand Singers perform outside Phoenix Civic Plaza to protest interference with gambling on Indian Reservations. (Published May 29, 1992) BOTTOM: Chris Rhodes of Phoenix, clad in traditional northern Plains Indian regalia, joins a protest march to the state Capitol. (Published May 21, 1992) TOP: Red Sand Singers perform outside Phoenix Civic Plaza to protest interference with gambling on Indian Reservations. (Published May 29, 1992) BOTTOM: Chris Rhodes of Phoenix, clad in traditional northern Plains Indian regalia, joins a protest march to the state Capitol. (Published May 21, 1992) LEFT: Red Sand Singers perform outside Phoenix Civic Plaza to protest interference with gambling on Indian Reservations. (Published May 29, 1992) RIGHT: Chris Rhodes of Phoenix, clad in traditional northern Plains Indian regalia, joins a protest march to the state Capitol. (Published May 21, 1992) JOHN SAMORA/THE REPUBLIC; SUZANNE STAR/THE REPUBLIC

Symington countered with his own proposal, and on May 22, he agreed to negotiate a gaming compact. Since then, other compacts have been enacted, the latest in 2021. The newest compact added sports betting, including phone apps, for both Native and non-Native venues.

The state still had no protocols to regulate any gambling other than dog and horse racing, so Tom Jones, who served on the first tribal gaming commission, helped develop bylaws and guidelines based on other states’ ordinances.

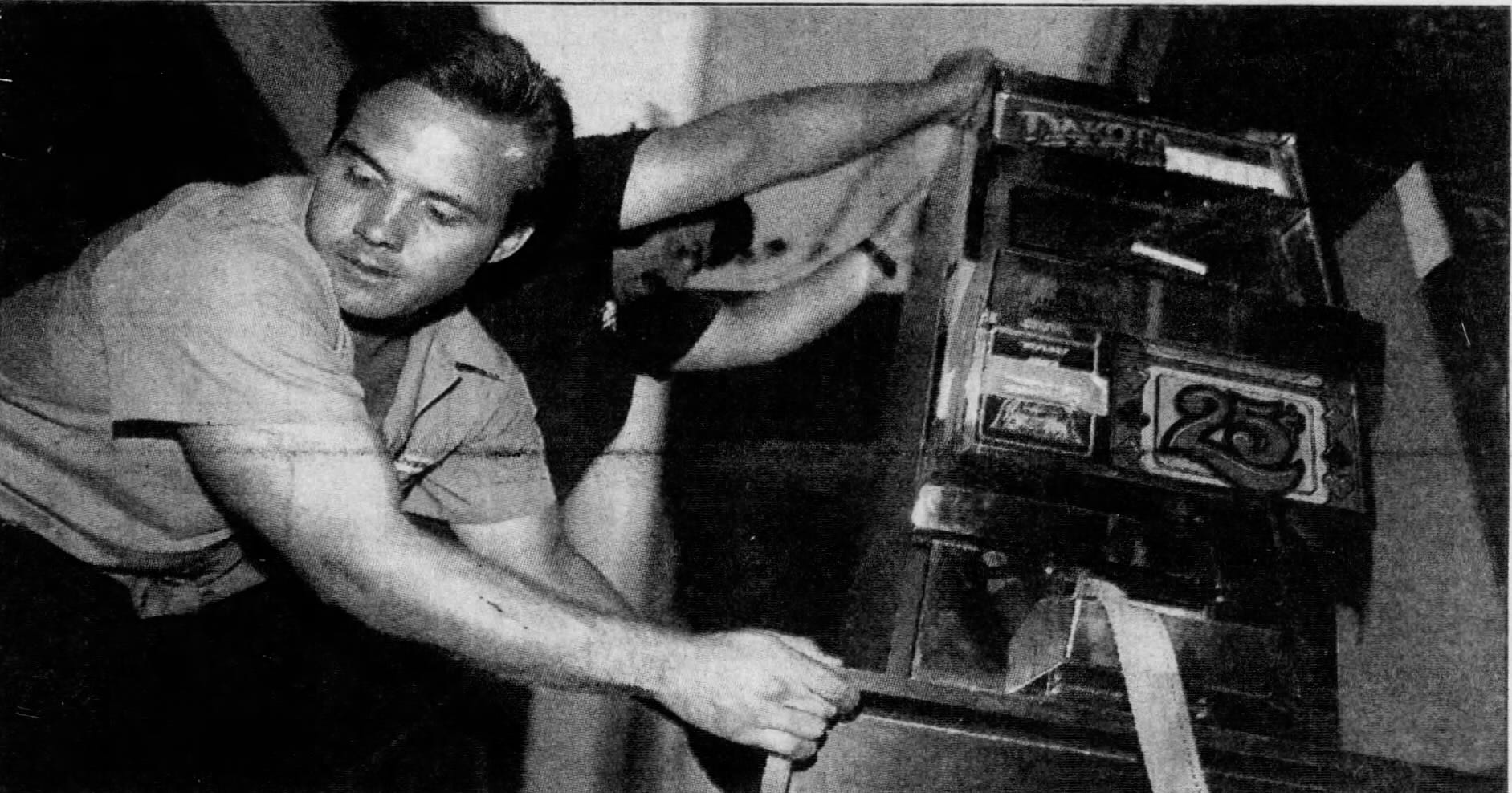

The gaming machines were taken to a Department of Public Safety warehouse in Phoenix on June 6, 1992, and were never seen again. To this day, some tribal members consider that a betrayal of their good faith negotiations, since the cooling-off agreement stipulated the machines would be sent to a neutral storage facility.

Workers unload a gambling machine at a Department of Public Safety warehouse. (Published June 6, 1992) Paul F. Gero/The Republic

Over the three decades that followed, tribes across the United States have reaped the benefits of gaming.

In 2020, there were at least 527 casinos operated by 247 tribes in 29 states, with an estimated $33 billion in revenue, according to media and technology law firm Gamma Law. Some tribes have expanded their gaming operations to other states and to the Las Vegas Strip.

Fort McDowell has added more than 200 new homes and a tribal health clinic, a state-of-the-art justice complex and water infrastructure using casino revenues. An early education complex was recently added to the community as well.

The tribe, now 870 members strong, has also added to its tourism attractions, with two championship golf courses, a luxury hotel, an RV resort and a Western entertainment venue. Fort McDowell also owns and operates a resort in Sedona.

Calvin “Roddy” Pilcher, a tribal member of the Fort McDowell Yavapai Nation, walks through the We-Ko-Pa Casino Resort in Fort McDowell, Arizona, on April 12, 2022. Pilcher served as cash operations manager for the tribe’s high stakes bingo during the standoff between the tribe and FBI agents who raided the former Fort McDowell Gaming Center in an attempt to seize the tribe’s slot machines in 1992. The standoff would pave the way for tribal gaming in the state and across the nation. Joel Angel Juarez/The Republic

A few years after the raid and standoff, Ella Doka organized a small walk to commemorate the event. The tribe has held the walk ever since, and May 12 is now a tribal holiday known as Sovereignty Day.

Symington was reelected as governor in 1994, only to resign in 1997 after being convicted for bank fraud in federal court. The conviction was later overturned and President Bill Clinton pardoned him in 2001. Symington retired from public life and obtained a degree in culinary arts. He also co-founded the Arizona Culinary Institute.

Pattea, who received an honorary doctorate from Northern Arizona University, continued to serve as Fort McDowell president for 17 of the next 21 years. He died in 2003 at age 81 and was succeeded by Burnette, who was most recently reelected in 2020. She spearheaded the construction of the new 167,000-square-foot casino and the renaming of Fort McDowell’s entertainment enterprises under the WeKoPa brand.

Burnette said her tribe’s stand against the federal and state governments’ attempt to take their business away is discussed widely today throughout Indian Country.

“It really opened the doors for Indian casinos, not only in Arizona but across the United States,” she said.

Rocha said the course of Indian gaming would likely have been much different had Fort McDowell not made its stand.

“Wherever I go, I always bring up the story because it’s such an important story,” said Rocha, the gaming expert and the publisher of Indian gaming news site Pechanga.net.

He added that the standoff gave Indian Country hope for a prosperous future.

“The lesson that Fort McDowell taught Indian Country is that you fight and you don’t accept it,” he said. “Its fight for its sovereign rights is a lesson that resonates. Even when they come to your home and they kick in the door and take your stuff out, the fight’s just started. It was just an incredible event and a touchstone for tribal sovereignty.”

Debra Krol reports on Indigenous communities at the confluence of climate, culture and commerce in Arizona and the Intermountain West. Reach Krol at debra.krol@azcentral.com. Follow her on Twitter at @debkrol.

Coverage of Indigenous issues at the intersection of climate, culture and commerce is supported by the Catena Foundation.

Krol worked as a reporter for Fort McDowell’s tribal newspaper from 2002 to 2007 and occasionally filled in as a tribal spokesperson.