Below we are republishing a 2019 post in which we excoriated the then Presidential candidate Kamala Harris for telling a whopper about her role in the get-banks-out-of-jail-almost-free card known at the National Mortgage Settlement in 2012. That deal was so bad that Gavin Newsom, at time the Lieutenant Governor of the Sunshine State, called it “deeply flawed” and “outrageous”.

Let us go back and explain why this settlement was so significant and how Harris and 13 other Democratic state attorney generals threw away a huge source of leverage with banks and mortgage servicers, which they could have used to extract much larger financial concessions as well are real reforms.

To this day, it is not well understood that Obama gave the banks a second monster bailout via this deal.1 Foreclosures kept rising after the crisis, peaking in 2009 and remained elevated in 2010.

To make a very long story short, some of these foreclosures were not warranted and many resulted in worse losses than a mortgage modification. This resulted from mortgage securitization and the rise of servicers who had no incentive to do their jobs all that well. In the hoary old days, the bank that issued your mortgage kept it on its books. When a homeowner got in arrears, the bank had an incentive to work out the loan if the borrower was at all salvageable.

Mortgage servicing was so bad that horror stories included foreclosures on homes where the borrower had never missed a payment, had never even had a mortgage, or the home had burned down and been paid off by insurance, yet the servicer was still pursuing the borrower. It was not simply that there were mistakes but that servicers would not fix them even when borrowers and their lawyers were persistent and provided documentation.

The looming problem was that servicers were paid to foreclose and not to make time-consuming mortgage modification. A group of loosely-affiliated lawyers who were defending borrowers discovered systematic flaws in how the mortgages had been securitized, calling into question whether the servicers were the party legally entitled to foreclose. And due to the rigid structure of the overwhelming majority of these securitizations, these problems could not be fixed via waivers or other actions. The robosigning scandal was an example of ex-post-facto but still impermissible efforts to remedy this mess.

These issues were not merely of documentation. They implied the securitizations had never been completed in the first place, meaning investors were holding a legal empty bag. As courts in many states, including some highly respected state supreme courts, validated many of the issues raised by foreclosure defense attorneys, it became clear to those watching closely that a tsunami of liability was bearing down on the originators of these mortgage securitications and the servicers.

The Obama administration had kinda-sorta woken up to the problem, forming a toothless effort to address the problem and work out a settlement. It was clear it was intended to be a sop to the banks. New York Attorney General Eric Schneiderman and 13 other Democratic state attorneys general, including Kamala, begin developing their own, more demanding, settlement deal, and it looked to have real odds of end-running the Federal effort (recall this makes sense because foreclosures are a state law matter). But Obama got Schneiderman to sell out for a mere seat next to Michelle at the State of the Union, and a promise to be part of a Federal task force. As we recounted at length, the Administration went out of its way later to humiliate Schneiderman. For instance, for months he had no office and when he got one, it had no phone.

As for the other attorneys general, if Kamala was the leader she pretended to be, with California being one of the most severely afflicted states, she could have stepped in after Schneiderman’s betrayal to lead the effort. Instead she got a few more gimmies to try to improve the stench of a bad deal.

This post first ran on January 10, 2019

The Big Whopper season is already upon us, in the form of presidential aspirants telling egregious lies about their track records. The Wall Street Journal tonight covers a section from Kamala Harris’ new book, in which she touts what a great deal she got for California homeowners in the so-called Federal-49 state National Mortgage Settlement in 2012.

The officials who played meaningful roles in the mortgage settlement negotiation should be run out of public life, rather than failing upwards, as Harris has. Hopefully, the millions who lost their homes to foreclosure will vigorously oppose her Presidential bid. But being a successful politician apparently means having no sense of shame.

Background: Why the National Mortgage Settlement Was a Bank Enrichment Scheme at the Expense of Homeowners and the General Public

In fact, as we and many others, like Dean Baker, Matt Stoller, David Dayen, Marcy Wheeler, Tom Adams, and Abigail Field recounted at the time, the settlement was a sellout to banks, a “get out of liability almost free” card. Due to widespread and probably pervasive corners-cutting during the mortgage securitization process, it appeared that the overwhelming majority of mortgages that had been securitized since the refi boom of 2003 had not had the mortgages conveyed to the securitization trusts as stipulated in the pooling and servicing agreements that governed these deals. Because these deals were designed to be rigid, for the ~80% that elected New York law to govern the trust, there was no way to straighten out these securitizations after the fact. Georgetown law professor Adam Levitin called these agreements “Frankenstein contracts” and argued that what had happened was “securitization fail,” that the securitizations had never been properly formed and thus the investors had bought what amounted to legal empty bags. Mind you, someone did have the right to collect the interest and principal from the mortgages, but that “someone” didn’t appear to be the servicers acting on behalf of the securitizations.

Nevertheless, in an early manifestation of what Lambert later called “Code is law,” everyone acted as if things had been done correctly. And weirdly, this might never have become a problem were it not for a tsunami of foreclosures. The dirty secret of mortgage servicing was it had been set up to be a high-volume, highly routinized business, which it could have been if servicers were dealing with on-time payments. But every time a servicer had a portfolio with a lot of delinquencies and defaults, it wound up engaging in a lot of fraud because it wasn’t paid enough to foreclose well, and certainly not enough to modify mortgages, as banks had done as a matter of course back in the stone ages when they kept mortgages on their books.

The securitizers and servicers all acted as if they could do the paperwork needed to convey the mortgage to the trust properly if and when they needed to foreclose. The wee problem with that was that for a whole bunch of good legal reasons we won’t bore you with (but we covered in gory detail back in the day) the mortgages had to have gotten to the trust by a date certain….which was inevitably well before the foreclosure. Only a time machine could fix this problem.

Servicers and foreclosure lawyers engaged in all sorts of creative frauds to try to make everything look OK. But with servicing so automated, botched, and too often deliberately abusive, quite a few of the people being foreclosed upon should have been salvaged. It would have been better for everyone, the investors, the homeowners, and the communities, except for those servicers (well, there was another bad incentive that we’ll get to in a minute). And many of the people who were foreclosed upon had missed only a payment or two, or would have been able to remain current with only a modest payment reduction. But some servicers like Wells Fargo would “pyramid” fees, impermissibly deducting a late fee first from borrower’s payment, guaranteeing that one late payment would result in all future payments being “short” and therefore late too, leading to more late fees.

And that’s before you get to mortgage horror stories of bad records combined with servicer refusals to make corrections. Foreclosures on houses that had never had a mortgage. Foreclosures on houses that had burned down where the servicer refused to take the insurer’s settlement check. Foreclosures by institutions the borrower had never dealt with. Foreclosures by multiple servicers on the same home. Foreclosures on active duty service members, which was prohibited by law.

Some homeowners who wanted modifications, aided by a small group of attorneys and activists, started to document the colossal mess of mortgage securitizations. Even though they usually lost in court, a few important cases did get to appeals and even state Supreme courts, and enough precedents were being set that the media was starting to treat the issue of foreclosure fraud seriously. It became national press in the fall of 2010 when GMAC halted all foreclosures due to what came to be called robosigning (which actually wound up being a huge break for the servicers, since it focused attention on false affidavits, which the banks spun as a mere paperwork problem for foreclosures which otherwise supposedly should go forward).

A sign that the problem of “securitization fail” was being seen as credible was when the Congressional Oversight Panel gave the issue prominent play in one of its reports.

Obama authorized a mortgage settlement initiative that was languishing in 2011. However, New York attorney general Eric Schneiderman and a group of about 14 other state attorneys general started working on a more ambitious settlement. Schneiderman’s campaign was gaining ground as of late 2011.

In early 2012, Obama succeeded in suborning Schneiderman. His price was getting to sit next to Michelle at the State of the Union Address and becoming co-chairman of a national mortgage task force that proved to be a complete joke. As we wrote in April 2012:

It was pretty obvious Schneiderman had been had. Obama tellingly did not mention his name in the SOTU. Schneiderman was only a co-chairman of the effort and would still stay on in his day job as state AG, begging the question of how much time he would be able to spend on the task force. His co-chairman is Lanny Breuer from the missing-in-action Department of Justice. And most important, no one on the committee was head of an agency, again demonstrating that this wasn’t a top Administration priority.

The Administration started undercutting Schneiderman almost immediately. He announced that the task force would have “hundreds” of investigators. Breuer said it would have only 55, a simply pathetic number (the far less costly savings & loan crisis had over 1000 FBI agents assigned to it). And they taunted him publicly by exposing that he hadn’t gotten a tougher release as he has claimed to justify his sabotage….

Mortgage Settlement Monitor Hires Firm that Has Worked on Countrywide Matters

But why, you might ask, was the settlement so bad? The headline amount was $25 billion across all banks and servicers, versus the potential liability of blowing up not just private mortgage securitizations, but even Fannie and Freddie deals. This was a meteor-with-the-potential-to-wipe-out-the-banks level liability. The Administration had all the leverage in the world to dictate terms. And instead it did what it liked to do best, a bailout with some gimmicks to improve the optics.

The banks didn’t come close to paying $25 billion. The cash portion of the settlement was under $5 billion. As we pointed out at the time, “That $26 billion is actually $5 billion of bank money and the rest is your money…That $5 billion divided among the big banks wouldn’t even represent a significant quarterly hit.” Contrast that with the $8.9 billion that one bank, BNP Paribas, paid to settle money laundering charges.

The rest was made up of non-cash items which cost the banks at best 10 cents on the dollar. It included giving them credit for things they were going to do anyhow, plus giving the banks credit for modifying mortgages they didn’t own, as in imposing costs on others.

Here’s one indicator of how well the settlement worked: Just 83,000 Homeowners Get First-Lien Principal Reductions from National Mortgage Settlement, 90 Percent Less Than Promised. And that gets to how the Administration likely rationalized it. Many of those securitized mortgages also had second mortgages on the same house. According to the lien priority, the second has to be modified first, and it has to be wiped out entirely before any modification of the first is to take place.

However, while banks securitized 75% of their subprime mortgages right before the crisis, they kept most of the seconds on their books. Yet the settlement explicitly allowed the seconds to stay put as the banks modified the firsts. From a February 2012 post:

As we had indicated earlier, one of the many leaks about the settlement showed that there had been a major shift its parameters. Of the $25 billion that has been bandied about as a settlement total for the biggest banks, comparatively little (less than $5 billion) is in cash. The rest comes in the form of credits for principal modifications of mortgages.

Originally, that was to come only from mortgages held by banks, meaning they would bear the costs. The fact that this meant that whether a homeowner might benefit would be random (were you one of the lucky ones whose mortgage had not been securitized?) was apparently used as an excuse to morph the deal into a huge win for them: allowing the banks to get credit for modifying mortgages that they don’t own.

The first rule of finance (well, maybe second, “fees are not negotiable” might be number one) is always use other people’s money before your own. So giving the banks permission to modify loans they don’t own guarantees that that is where the overwhelming majority of mortgage modifications will take place, ex those the banks would have done anyhow on their own loans. And the design of the program, that securitized loans will be given only half the credit towards the total, versus 100% for loans the banks own, merely assures that even more damage will be done to investors to pay for the servicers’ misdeeds.

Let me stress: this is a huge bailout for the banks. The settlement amounts to a transfer from retirement accounts (pension funds, 401 (k)s) and insurers to the banks. And without this subsidy, the biggest banks would be in serious trouble

Why? As leading mortgage analyst Laurie Goodman pointed out in a late 2010 presentation, just over half of the private label (non-Fannie/Freddie) securitizations have second liens behind them (overwhelmingly home equity lines of credit). Moreover, homes with first liens only have far lower delinquency rates than homes with both first and second liens. Separately, various studies have found that defaults are also correlated with how far underwater a borrower is. If a borrower is too far in negative equity territory, it makes less sense for them to struggle to stay current, no matter how much they love their home.

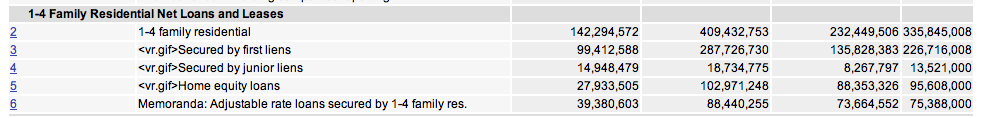

The second liens pose a huge problem to the banks. Courtesy Josh Rosner, this is data as of September 30 for Citi, Bank of America, JP Morgan, and Wells, respectively:

Compare these totals with the book value of their equity as of the same date: $42 billion in seconds for Citi versus $177 billion in equity; BofA, $121 billion in seconds versus $230 billion in equity: JP Morgan, $97 billion in seconds versus $182 billion in equity; Well, $109 billion in seconds versus $139 billion in equity. One of my mortgage investor mavens says that BofA’s seconds should bve written down by about $100 billion and JP Morgan’s by $60 billion. That writeoff would exceed BofA’s market cap and would make a major dent in Jamie Dimon’s touted “fortress balance sheet.” And a similar magnitude of haircut to Wells would expose it as being grossly undercapitalized.

And as Matt Stoller documented, one of the big ways that the settlement got better press than it deserved was that the states used some of the cash they’d gotten to buy off housing activists. Those organizations are chronically budget starved, so it took remarkably little to purchase their acquiescence.

Now you might be saying, “I understand how the settlement might have hurt people who were facing foreclosure. But I wasn’t one of them. How can you say it hurt me?”

Foreclosures hurt state and local tax revenues. A foreclosure depresses home values in the neighborhood, usually by 10%. Banks would typically do a terrible job of securing and maintaining the property. Private equity firms later swept in and tried acting as a landlords of single-family homes. For the most part, they did succeed in raising rents, but most have proven to be poor landlords, and don’t do a good job of maintaining the houses, even neglecting to address leaks, which do fast and serious damage. Having transient residents and not-well maintained properties isn’t good for housing values in the long term.

Kamala Harris’ Dodgy Role

Now it is fair to say that Harris got a better deal for California than the other state attorneys generals got. But that is what the Japanese would call a height competition among peanuts.

The recap from the Journal:

Ms. Harris writes that under the initial settlement offer, California would have received between $2 billion and $4 billion, calling it “crumbs on the table” that would have failed to properly compensate homeowners…

Ms. Harris describes a testy phone call in early 2012 with Mr. Dimon as they discussed the deal. “We were like dogs in a fight,” she writes.

“‘You’re trying to steal from my shareholders!’ he yelled, almost as soon as he heard my voice,” Ms. Harris writes of Mr. Dimon. “I gave it right back. ‘Your shareholders? Your shareholders? My shareholders are the homeowners of California! You come and see them. Talk to them about who got robbed.’”…

Two weeks later, Ms. Harris writes, the five banks relented and eventually agreed to a settlement that year of $26 billion, which ultimately provided about $50 billion in gross relief to homeowners. California’s share of the deal reached $20 billion in aid to the homeowners, a significant increase over the original settlement offer. The agreement involved 49 states and the District of Columbia and five major banks: Bank of America Corp. , Citigroup Inc., JPMorgan Chase, Wells Fargo & Co. and Ally Financial Inc.

This is nonsense. Harris did get a good bit more for California but the claim that she was responsible for a ginormous increase and that the total value of the settlement was on the order of $50 billion is unadulterated tripe. The larded settlement gross number was up to $19 billion with New York and California still dickering. Even though California, by virtue of having more foreclosures than any other state, did have more leverage than other states, Schneiderman filed a MERS suit that got folded into the settlement that also resulted in more concessions.

Curiously, Harris does not mention that Governor Jerry Brown raided most of the settlement money and diverted it to fill state budget gaps, with the legislature’s approval. Last year, a state appeals court ordered California to use the funds for their intended purpose: to help victims of foreclosures. This is now so many years after the fact that any monies will come after the former homeowners are past the point of their most acute distress.

But the piece de resistance comes from a Jacobin story on Harris’ record:

At the time [when Harris decided to push for a better deal], Harris was under pressure from union leaders, other politicians, and housing rights activists. As one member of the progressive coalition of groups put it, “It wasn’t like she was some hard-charging AG that wanted to take on the banks” — rather, “it took a lot of work to get her where we needed her to be.” Harris withdrew the day after these groups sent her a letter, signed on by Lt. Governor Gavin Newsom, a potential future rival, calling the deal “deeply flawed” and “outrageous.”

Even a Wall Street Journal reader was offended by the article:

Daniel Skoglund

MAGA idiots spamming this thread with BS talking points.I’m a “librul”, and I detest Harris for legitimate reasons:

-Didn’t prosecute Steve Mnuchin when she was CA AG.

-Is meeting with Wall Street donors while she claims to be AGAINST Wall Street?

-Endorsed Hillary and met with her donor network.She’s another corporate Democrat. I’m interested in grassroots people.

EDIT: Also, Hillary was rumored to make Jamie Dimon her Treasury Secretary, who apparently Harris despises, but she was okay with endorsing her? lol…

And if you need more proof of Harris’ puffery, we have lots more evidence in our archives. Some examples:

The Top Twelve Reasons Why You Should Hate the Mortgage Settlement

Quelle Surprise! Administration and State Attorneys General Lied, Mortgage Settlement Release Described as “Broad”

Abigail Field: Hiding the Enforcement Fraud at the Heart of the Mortgage Settlement

If this is the best story Harris has to tell, it doesn’t bode well to her holding up under meaningful oppo.

_____

.1 It is a mistake to think that Obama did not play a role in the rescues while Bush was still President. Obama and McCain were included in major Treasury briefings about rescue scheme after Lehman failed. When the first version of the TARP received fierce criticism from all across the political spectrum and Mr. Market went into another swan dive, Obama whipping for the second version was critical to its passage. As for QE (and do not tell me the Fed was independent during the crisis; the Fed and Treasury were coordinating tightly on salvage operations) for those who bothered listening to Bernanke, QE was to lower mortgage interest rates and their spreads over Treasuries. That was to try to goose housing prices. Borrowers who were in financial stress due to having lost their job or having their hours or pay cut would be less motivated to struggle to keep their house if it was deeply underwater (this is not theory; data at the time bore that concern out)