Yves here. Hubert Horan continues with his long-running series on Uber, showing that after 13 years, Uber is getting close to break even. Needless to say, all the billions invested to fund among other things billions in losses will not be recouped. But many of the promoters successfully relied on greater fool theory.

Yet again, he does the job the business press has failed to do: carefully parsing Uber financials and explaining what they say. Hubert highlights one factor driving margin improvement which may not have gotten the attention it deserves; Uber using data about individual driver and passenger behavior to tailor prices so as to better fleece them.

Hubert argues that Uber has taken all of its margin-improving tactics as far as they go (save perhaps restructuring UberEats) and projecting more increases would be a mistake.

Please also stay tuned for his review of anti-trust issues.

By Hubert Horan, who has 40 years of experience in the management and regulation of transportation companies (primarily airlines). Horan has no financial links with any urban car service industry competitors, investors or regulators, or any firms that work on behalf of industry participants.

After $33 Billion in Losses Over 14 Years, Uber is Finally Approaching GAAP Breakeven

Uber claimed its first ever quarterly GAAP profit when it released its second quarter and first half financial results on August 1. [1] The claim was a bit of stretch as the reported $394 million second quarter profit ($237 million for the first half) was entirely explained by an alleged $386 million second quarter gain ($707 million in the first half) in the value of untradable securities they hold in companies like Didi, Grab, and Aurora that have nothing to do with their ongoing operations. Readers of this series will know that Uber has aggressively used claims like this to justify misleading claims about its corporate financial performance ever since 2018 when it inflated published net income numbers by $5.8 billion just prior to its IPO. [2]

Even if the recently published numbers must be taken with a few grains of salt, Uber has achieved noteworthy loss reductions and margin improvements in the last two years. Year over year Uber achieved a $932 million improvement in net income and an 11.4% improvement in net margin. [3]

Lyft has also reduced losses but is still some distance from breakeven, losing $1.13 million in the second quarter and $300 million in the first half. [4]

![]()

The biggest question for investors is whether they can count on similarly strong net income and net margin improvements in the coming years and demonstrate the strong and sustainable profit growth needed to justify huge corporate valuations. The fact that Lyft has emerged from intensive care and Uber can now walk upright does not mean that either company’s finances are now fully healthy.

Answering this question is made more difficult by Uber’s refusal to present a coherent explanation for its strong margin improvement, or why it has produced stronger margins than Lyft. Its financial reporting prevents investors from analyzing even the most rudimentary performance issues (e.g., how much of revenue growth was due to increased volume versus higher unit prices?). Uber’s claim that the financial improvement was driven by revenue growth makes no sense. The fact that its much more robust pre-pandemic revenue growth led to multi-billion-dollar losses demonstrated Uber’s lack of significant scale economies. Expanding unprofitable operations just increases total losses. Only major changes could have driven these margin changes (both absolute and relative to Lyft) but Uber doesn’t want to discuss them openly.

Similarly, Lyft’s only explanations were that “[t]he rideshare market is growing” and “[o]ur customer obsession is paying off.”

The Four Factors That Drove Uber’s Margin Improvements in the Last Two Years

Uber’s first action to address the combination of ongoing losses and the financial devastation of the pandemic was to abandon the ridiculous long-term development projects that it had been pursuing under both Travis Kalanick and Dara Khosrowshahi, including efforts to become a leader in the development of autonomous vehicle technology, and efforts to develop urban transport services beyond its core car service market (scooters, flying cars, transit services). Uber abandoned some hopelessly unprofitable overseas markets and shrank back to being a pure car service and food delivery company (plus a tiny freight operation), eliminating major cost centers that had no hope of generating revenue on any reasonable timeframe. Lyft had wasted much less money on these highly speculative long-term projects, although it is still working to unwind its failed scooter investments. But firing 24% of its staff at the end of 2022 clearly provided an important P&L boost.

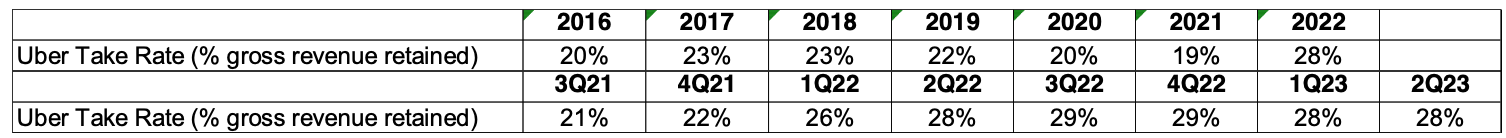

The second factor as documented in the table below, is that starting in early 2022, Uber began keeping a larger share of gross customer payments and giving a smaller share to drivers. Until the 2020 pandemic demand collapse Uber took roughly 22% of gross customer payments. It restored that rate in the second half of 2021 but then increased its take rate to 28-29%. This was not because Uber was providing an increasing portion of what customers valued. Uber simply figured out how to transfer over $1 billion in revenue per quarter from drivers to Uber shareholders.

The third factor, the delinking of passenger fares and driver compensation was a major driver of this labor to capital wealth transfer. Prior to 2022, driver payments were a function of what passengers paid, with adjustments for incentive programs and peak period demand. Uber has developed algorithms for tailoring customer prices based on what they believe individual customers would be willing to pay and tailoring payments to individual drivers so they are as low as possible to get them to accept trips.

This is fundamentally different from Uber’s pre-pandemic price discrimination, where it could apply Surge Pricing during periods of high customer demand (or driver shortages) but any customer in a given zone requesting the same trip at the same time would see the same price, and drivers would receive the same payment for those trips. Now different passengers/drivers making the same trip can see very different fares/payments. System average revenue per trip goes up, average driver payments per trip go down. Airlines have decades of experience changing fares depending on demand but have no ability to discriminate between passengers booking the same flight at the same time. [5]

The fourth factor is that Uber has significantly cut back service on the big service expansion that made them so popular prior to the pandemic. This made it much easier to get rides during peak demand periods and to the lower demand neighborhoods that traditional taxis had served poorly, but this approach hemorrhaged cash. Uber has reverted to the more economical traditional taxi approach, focusing on the narrow area of cities with the densest demand. [6] This increases the total (Uber plus driver) revenue potential of each driver shift, making it more likely that drivers, even if receiving a smaller share of customer payments, will find it worthwhile to spend time driving for Uber.

Thus 6-7% of Uber’s 11% net margin improvement appears to come from the algorithmic price discrimination changes and the service cutbacks that allowed it to increasing its take rate from 22% to 28-29%. The balance appears to reflect the elimination of the costs associated with hopeless markets and businesses.

Uber stock outperformed Lyft in 4Q22 and 1Q23 due to the appearance that Uber was gaining revenue share from Lyft. Although this cannot be fully analyzed using public data, it suggests that Uber had done more algorithmic price discrimination and reductions in service scope than Lyft. Lyft had difficulty both in matching Uber prices and convincing drivers to serve Uber customers. But average revenue pre trip fell for both companies in 2Q23 as Lyft seemed to be stemming its revenue share declines.

Most of the Potential P&L Gains from Uber’s Recent Moves Have Been Exhausted

Unfortunately, the large improvements that resulted from higher take rates and the elimination of totally unproductive expenses were (like Lyft’s huge staff cuts) one-time improvements that cannot drive larger margin gains going forward.

While many on Wall Street think suppressing driver wages even further and transferring that wealth to capital would be a splendid thing, Khosrowshahi has stated that he does not think increasing take rates above 30% would be a good thing. [7] He understands that if drivers are angered/alienated beyond a certain point or feel that they will not earn enough money to cover basic costs, they would stop driving and Uber’s ability to meet customer demand could quickly collapse, and that service collapse could spook investors expecting steady profit growth. He also understands that Lyft’s new senior executives have become much more focused on maintaining pricing parity and Uber efforts to squeeze drivers further could quickly push drivers towards Lyft and give them a service advantage.

It is hard to believe that Uber (or the Uber/Lyft duopoly) could continue to increase both prices and traffic volume. Given the chaos of the pandemic and the return of inflation, customers in many service industries simply accepted whatever higher prices were offered. But unless the laws of supply and demand have been permanently reversed, they cannot use higher prices to drive ongoing revenue growth without choking off traffic growth.

Uber’s early meteoric growth was based on extreme predation. It offered hopelessly uneconomic prices and capacity to grow demand and eliminate competition, and its ruthless behavior ensured that no competitor (other than Lyft) could survive if they tried to challenge them. But even if Uber’s successful predation gives them more leeway to sustain supra-competitive prices (and service reductions) without risk of market discipline, Uber will still struggle with the conflict between higher fares and lower (or negative) growth.

The only remaining opportunity to significantly reduce expenses that are not producing financial returns would be a major restructuring of Uber Eats. While Uber’s food delivery operations helped keep the lights on during the pandemic, Uber remains trapped with a weak position in an industry that Is fundamentally unprofitable and where the pandemic fueled demand for home delivery has dissipated. As noted, this cannot drive further margin gains at Lyft.

Everything Uber Has Done to Improve The P&L Contradicts its Narrative Claims About the Potential for Long Term Equity Appreciation

The combination of these challenges could fatally undermine the investor support that has sustained Uber’s stock price. As this series has documented at length Uber’s greatest accomplishment was its ability to construct narratives about its underlying strengths and huge future equity appreciation potential. The narrative claims developed under Kalanick about using innovative technology to disrupt backward industries, and using low fares and expanded capacity to pursue global industry dominance convinced investors to think that Uber had the same economics and same long-term equity appreciation potential as unicorns like Amazon. Thus, investors expected Uber to rapidly covert early losses into years of robust volume and profit growth in its core business, and then profitably expand into many related businesses. In the 2019 IPO Khosrowshahi distracted attention away from Uber’s uncompetitive economics and awful financial results by doubling down on go-go growth narratives. Investors were told that Uber is a highly dynamic company with great long-term prospects that would become the “Amazon of Transportation.”

Uber’s reluctance to explain how it improved margins and established a P&L advantage versus Lyft is because the explanation directly contradicts these corporate narratives, and because the explanation would help investors see that the recent rate of margin gains is not sustainable.

Uber has abandoned everything that got the market to enthusiastically support them 10 years ago. Uber is now just a much higher cost version of the traditional operators they vilified as an “evil taxi cartel”. Their fares are now higher than traditional taxis used to charge, they no longer offer a lot more cars in peak periods and they no longer serve neighborhoods throughout each city. Uber has completely abandoned its original “megagrowth driven by much more service at much lower prices” strategy but still tells investors that robust growth will drive future equity appreciation. Every Uber attempt to mimic Amazon’s expansion beyond its core market has also failed.

From a narrow P&L perspective Uber’s recent moves to cut service and raise prices are sensible, but if openly discussed investors could realize that the entire corporate growth narrative was always a sham. Investors would stop seeing Uber as a dynamic fast-growing “tech” company and would realize it was simply a player in the economically difficult and slowly growing urban car service industry. Investors applauded Uber for introducing innovative technology that “disrupted” a backward industry and brought huge benefits to consumers and cities.

It does not want those investors to see that the Uber’s “innovative technology” is focused on the algorithmic exploitation of both customers and drivers. It does not want investors to see that none of its recent P&L gains were due to true productivity improvements and thus these gains cannot be extrapolated into the future.

Going forward Uber must deal with the enormous tension between the things it has done to get the company closer to breakeven, and the narratives it uses to maintain strong demand for its stock. As documented in Part 32, the residual power of Uber’s growth narrative was strong enough to sustain its share price in 2022 when the value of a wide range of narrative-based “tech” startups that had never demonstrated sustainable profitability fell by 60-90%. [8] These tensions emerged when Uber’s share price actually fell after it announced its first ever operating profit because investors realized revenue had grown much less than a growth company like Uber should have achieved. [9]

Some analysts suggested that the Lyft-to-Uber revenue share shifts of recent quarters would trigger a Lyft doom-loop, and a much higher Uber share price could be justified by its inevitable capture of the entire Uber-plus-Lyft market. This was always wildly improbable. Both companies had survived despite years of huge losses; there was nothing to suggest Lyft was anywhere near total collapse. Lyft would only be willing to be bought out at huge price that rewarded Lyft’s currently underwater investors. Any such merger would be so blatantly anti-competitive that the antitrust authorities would have to challenge it. And Lyft’s recent efforts to stem the revenue share losses eliminates any near-term doom-loop threat.

The Antitrust Case Against Uber

Since this series began in 2016, I have argued that Uber’s growth strategy had always been explicitly based on anti-competitive predatory behavior. Uber owned none of the vehicles used to serve customers and required very few capital assets, but investors provided a staggeringly unprecedented level of initial funding ($13 billion by 2015; $18 billion by 2018). This funding was used to overwhelm markets with car capacity at fares that came nowhere close to covering actual costs. It was also used to mount massive PR and lobbying programs designed to distract attention from the massive losses these subsidies created. Uber worked aggressively to convince markets (and journalists and politicians) that its meteoric growth was based on huge technological advances that had transformed a backward industry, and that its Amazon-like economics would drive years of strong equity appreciation.

Even though Uber was openly pursuing global market domination, and its $33 billion in losses clearly demonstrated that it was substantially less efficient than the thousands of taxi operators it had driven out of business, no one made any attempt to argue that Uber had violated the antitrust laws prohibiting predatory competition. This was because predation cases, which were common before 1970 became extinct after courts embraced Chicago School claims that there was no rational basis for companies to even consider predatory behavior.

As with many aspects of the Chicago School’s efforts to nullify antitrust protections, the underlying academic arguments included important caveats and depended on the industry/market contexts of the examples cited, but the courts methodically converted these arguments to simplistic, ironclad prohibitions against enforcing the written statutes, independent of any case-specific evidence.

A key 1975 paper by Areeda and Turner’s [10] plausibly claimed that that predatory pricing “seems highly unlikely” because of the huge costs and risks of major price wars in an established industry with established production economics but recognized there was still might be cases of companies “not competing on the merits”. But the 1986 Matsushita case created the general rule that predation cases shouldn’t be taken seriously (“predatory pricing schemes are rarely tried, and even more rarely successful.”) and since competitive harms weren’t sustainable they could be dismissed because they didn’t pose lasting risks to consumers. The 1993 Brooke case (about predatory efforts by large tobacco companies to eliminate competition from generic brands) established a total prohibition of predation cases by establishing the insurmountable demand that plaintiffs had to prove there was a “dangerous probability” that the company engaging in predation could fully recoup its losses through supra-competitive prices that future market entry could not discipline. [11]

Among many other flaws, the Chicago School efforts to rewrite the antitrust statutes implicitly assumed that every company had somewhat similar production economics, that corporate valuations were a direct function of its near-term P&L results and that barriers to new competitive entry in every industry were reasonably low. Predatory behavior would be rare and economically irrational under these conditions because any attempt to use a major price war to kill off competitors would be enormously costly to the predator, investors would have little interest or ability to fund large losses during the price war, and even if it temporarily succeeded new competition could quickly emerge to discipline the predator.

Section 2 of the Sherman Act and the Robinson-Patman Act were explicitly designed to prohibit what Uber actually did. It was pricing far below cost in order to drive smaller companies out of business while it pursued industry dominance. It not only had no efficiency advantages over the smaller companies but actually had huge cost disadvantages. It had none of the massive scale or network economies that have justified temporary below-cost pricing in other cases. As opposed to the electronics and tobacco companies in the previous court cases the staggering magnitude of Uber’s financing advantage made it easy to win a predatory battle, and created a massive barrier to any future competitor that did not have eleven-digit levels of funding. Secure in its dominant market position, Uber has already reduced capacity and raised prices to levels much worse than consumers experienced before Uber’s market entry. In addition to the massive misallocation of capital, Uber’s predation imposed other significant external costs, including reduced productivity and innovation due to the elimination of competition, the destruction of a previously viable portion of transport service in hundreds of cities, and the losses of drivers whose compensation has been reduced to minimum wage levels.

A recently published draft of a forthcoming law journal article by Matthew Wamsley and Samuel Weinstein attempts to lay out an approach by which Uber could be sued on antitrust grounds. [12] A useful summary of the issues and arguments was published by Business Insider. [13] Wamsley and Weinstein clearly understand that Uber were clearly engaged in the type of predatory behavior prohibited by those statutes, however they also pragmatically recognize that because the courts reviewing antitrust cases have been overwhelmingly captured by Chicago School ideology “there does not yet appear to be any realistic chance that Brooke Group will be overruled.” So instead of attempting to overturn the cases that gutted laws against predation, the article shows that a strong case against Uber can be made while strictly observing the criteria established in Matsushita and Brooke.

In order to get around the “companies have no rational basis to pursue predation” argument, the article correctly demonstrates that Uber’s predation was never intended to generate near-term P&L gains, but successfully supported Uber’s original investors’ central objective of maximizing the value that their shares could achieve once the company went public.

The relevant economic actors in Uber and other “tech” startup cases are the venture capital firms that participated in early funding rounds. Their investment approach was totally different from the shareholders of most established companies in the mid/late 20th century. These VC firms provided Uber’s funding, controlled Uber’s Board, and directed Uber’s strategy. They could achieve fabulous riches just by getting to the IPO that allowed them to convert the hypothetical value of their investments into cold hard cash. The narratives Uber’s original owners and executives promulgated pumped up demand for the IPO by creating the false narratives about Amazon like economics and long-term equity appreciation potential, that meant investors could ignore the dreadful financial numbers in the S-1. [14]

Benchmark Capital invested $9 million in Uber’s Series A. After Uber’s IPO its return on this investment was $5. 8 billion. Travis Kalanick cashed in $1.4 billion in shares after the IPO while still holding shares worth an additional $5.3 billion. Thus the Matsushita test of rationality has clearly been met, even though neither Benchmark (the largest initial investor) nor Kalanick (the CEO) had done anything to establish a company that had any hope of strong sustainable profits. Benchmark and Kalanick had not only met the Brooke test of clearly recouping the initial losses from predation but had achieved returns from predation that John D. Rockefeller and the Standard Oil Company could have only dreamed of.

My only quibbles with Wamsley and Weinstein’s article is that it missed a few points that would have made their case even stronger. They included very little of the available P&L data that demonstrates the magnitude of the predation, and that none of the predation-fueled growth was part of a plausible plan to generate sustainable profits. They did not seem to be aware of magnitude and power of Uber’s PR/propaganda efforts which would be key to demonstrating that Uber’s early investors had a highly rational plan to create the investor perceptions that allowed them to recoup the costs of their predation after the IPO. [15] Their point that the early-stage investor funding financed the predation would have been stronger if they had quoted numbers showing the massive size of that war chest, or if they had pointed out that Uber’s investors provided 2300 time the pre-IPO funding of Amazon, whose growth strategy was not based on predation. They incorrectly assumed that Kalanick was ousted by the Board because of bad publicity from various scandals, when the real reason was Kalanick’s failure to implement the IPO as quickly as the early-stage investors wanted. [16] They incorrectly claimed that Uber’s “network economies” could be a partial explanation of why Uber grew so fast and why no one has attempted to compete with them. But Uber never had any of the “Metcalfe’s Law” type network economies that other “tech” companies exploited [17] and no one wanted to try and compete with a company that still has over $6 billion in cash on hand and a proven track record of ruthlessly attacking any and all challengers.

Again, none of these quibbles undermines the core argument that Uber clearly pursued the type of predatory behavior that Section 2 of the Sherman Act and the Robinson-Patman Act were explicitly designed to prohibit, and that this can be demonstrated in a way that overcomes Matsushita-type objections that predation is irrational and cannot materially harm consumers, and overcomes Brooke-type requirements showing returns to predation that fully recoup the losses incurred.

I have absolutely no expectation that anyone will pursue an antitrust case against Uber on these grounds, but it is useful to point out that Uber’s entire corporate development strategy violated the law, and Uber would have failed long ago had anyone enforced the law.

_________

[1] Preetika Rana, Uber’s Business Is Finally Making Money After Years of Losses, Wall Street Journal, 1 August 2023, Uber 10Q statement for second quarter 2023 Available at https://investor.uber.com/financials/default.aspx

[2] Can Uber Ever Deliver? Part Nineteen: Uber’s IPO Prospectus Overstates Its 2018 Profit Improvement by $5 Billion, Naked Capitalism, 15 April 2019; Can Uber Ever Deliver? Part Twenty-Nine: Despite Massive Price Increases Uber Losses Top $31 Billion, Naked Capitalism, February 11, 2022, presented a more detailed version of this table showing financial results starting in 2014. The problem with including the hypothetical impacts of securities received when failed operations were discontinued is that it creates wild swings in reported Uber Net Income, making it extremely difficult for outsiders to understand how the performance of Uber’s ongoing operations is changing. Data in these tables from 2019 (and earlier) also adjust published results to spread stock-based compensation expense realized immediately after Uber’s 2019 IPO across a longer time period. In this case Uber was following proper accounting practices but adjustments required to accurately show financial trends over time.

[3] All expense and net income numbers in this discussion exclude the impacts of discontinued operations.

[4] Lyft Announces Results for Second Quarter 2023, https://investor.lyft.com/news-and-events/news/news-details/2023/Lyft-Announces-Results-for-Second-Quarter-2023/default.aspx

[5] Airline pricing is completely transparent; frequent flyers and internet booking sites would immediately if airlines tried to force some customers to pay higher fares than others for the same service. In contrast Uber passengers have no way of knowing if the fare they are shown is “fair”. And Uber has worked aggressively to prevent drivers from using tools that would allow them to see what other drivers are being paid, or when Uber is surging fares in specific areas.

[6] First discussed in this series at Can Uber Ever Deliver? Part Two: Understanding Uber’s Uncompetitive Costs, Naked Capitalism, 1 December 2016

[7] Interview of Khosrowshahi by Ben Gilbert and David Rosenthal, www.acquired.com, 12 June 2023

[8] Can Uber Ever Deliver? Part Thirty-Two: Losses Top $33 Billion But Uber Has Avoided the Equity Collapse Most “Tech” Startups Experienced, Naked Capitalism 27 February 2023

[9] Christina Falso, Uber shares dip after mixed second-quarter results. Here’s what the pros are saying, CNBC, 1 August 2023 Yiwen Lu, Uber Posts 14% Rise in Revenue as Growth Slows, New York Times, 1 August 2023,

[10] Phillip Areeda & Donald F. Turner, Predatory Pricing and Related Practices Under Section 2 of the Sherman Act, 88 Harv. L. Rev. 697 (1975).

[11] Matsushita Elec. Indus. Co. v. Zenith Radio Corp., 475 U.S. 574, 589 (1986); 14 Brooke Grp. Ltd. v. Brown & Williamson Tobacco Corp., 509 U.S. 209, 224 (1993).

[12] Wansley, Matthew and Weinstein, Samuel, Venture Predation (May 3, 2023). Journal of Corporation Law, Forthcoming, Cardozo Legal Studies Research Paper, No. 708, Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=4437360. While Uber is the primary example cited the article also discusses the predatory behavior of similar companies such as WeWork and Bird.

[13] Adam Rogers, The dirty little secret that could bring down Big Tech, Business Insider Jul 18 2023, https://www.businessinsider.com/venture-capital-big-tech-antitrust-predatory-pricing-uber-wework-bird-2023-7

[14] Can Uber Ever Deliver? Part Nineteen

[15] I first described Uber’s manufactured narratives in Can Uber Ever Deliver? Part Three: Understanding False Claims About Uber’s Innovation and Competitive Advantages, Naked Capitalism 2 December 2016. They are more fully documented in a four-part series that began with Hubert Horan, The Uber Bubble: Why Is a Company That Lost $20 Billion Claimed to Be Successful? Promarket, November 20, 2019, https://promarket.org/the-uber-bubble-why-is-a-company-that-lost-20-billion-claimed-to-be-successful/

[16] The Board rebellion that led to Kalanick’s ouster is described at Can Uber Ever Deliver? Part Ten: The Uber Death Watch Begins, Naked Capitalism, 15 June 2017

[17] These network economies are when the value of a service to individual users increases significantly as more and more people use the service. Classic examples are Ebay and Facebook. Uber users care about the availability of car service at attractive prices when they need a ride but do not care about the size of Uber’s overall user base.