By Lambert Strether of Corrente

Since we seem to be in an apocalyptic mode just now, here are some headlines from last week:

Fireflies are fading from Maine’s night skies Portland Press-Herald

The number of monarch butterflies and other Wisconsin pollinators are falling. Here’s why Wisconsin Farmer

Where have all the wasps gone? BBC

But does this add up to an apocalypse? An extinction-level event? Some urge caution (from the early 2020’s: “nuanced“, “more complicated than thought“, “not so fast“). But since an insect apocalypse is a “risk of ruin” event, I think it makes sense to view it through a precautionary lens. In this post, I’ll do a quick survey of the literature, look at the weaknesses of the field, and then the causes and effects of insect “decline” (if “apocalypse” is too much; but regardless, on either a geological or even a history timescale, apocalypse is what we’re looking at, quarterly results aside).

Now let’s turn to the literature (PNAS has a fine history here). First, some country studies. From ITV, the UK, “Dramatic decline in insect populations over last 50 years, Sussex study finds”:

A survey of farmland in Sussex, carried out for more than 50 years, has seen a dramatic decline in insect populations.

The study tests the number of different insects present on cereal crops which overall has revealed that numbers have dropped by 37%.

It is done by using a vacuum backpack to sample the insects living amongst the cereal.

From the Sierra Club, the United States, “Study Shows Western Monarchs Have Dropped 97% in 35 Years“:

There’s been a lot of handwringing about monarch butterflies (Danaus plexippus) in the eastern United States, where the population of the migratory insects has declined from an estimated 1 billion insects in 1996 to about 100 million last year. The charismatic orange and black butterflies are iconic in part because of their epic 2,000-plus mile journey to a single overwintering spot in Mexico’s Sierra Madre Mountains. But a new study shows that the other major population of monarchs, which live in the western United States and overwinter on the California Coast, is suffering even steeper declines than its eastern siblings.

The study, published in the journal Biological Conservation, shows that in the last 35 years, the population of western monarchs has plummeted from about 10 million living along the west coast to approximately 300,000. Even more concerning, if present trends continue, the study indicates the western population faces a 72 percent extinction probability over 20 years and an 86 percent risk over the next 50 years.

Monarchs are a single charismatic species — charismatic species, like polar bears or pandas, get disproportionate amounts of attention. And funding — but there are more insect species in trouble. From Statista, “Massive Insect Decline Threatens Collapse Of Nature” (2019), a handy chart:

Granted, dragonflies and (honey) bees are still pretty charismatic, but here is a review of the literature, “Insect population faces ‘catastrophic’ collapse: Sydney research” (2019):

A research review into the decline of insect populations has revealed a catastrophic threat exists to 40 percent of species over the next 100 years, with butterflies, moths, dragonflies, bees, ants and dung beetles most at risk…. “As insects comprise about two thirds of all terrestrial species on Earth, the trends confirm that the sixth major extinction event is profoundly impacting life forms on our planet,” write Dr Sanchez-Bayo and co-author Dr Kris Wyckhuys from the University of Queensland and the Institute of Plant Protection, China Academy of Agricultural Sciences, Beijing. Their study was published this week in Biological Conservation. It involved a comprehensive review of 73 historical reports of insect declines from across the globe, systematically assessing the underlying drivers of the population declines.

“Because insects constitute the world’s most abundant animal group and provide critical services within ecosystems, such an event cannot be ignored and should prompt decisive action to avert a catastrophic collapse of nature’s ecosystems,” the report said.

Another. From PNAS, “Insect decline in the Anthropocene: Death by a thousand cuts” (2021):

While there is much variation—across time, space, and taxonomic lineage—reported rates of annual decline in abundance frequently fall around 1 to 2% (e.g., refs. 12, 13, 17, 18, 30, and 31). Because these rates, based on abundance, are likely reflective of those for insect biomass [see Hallmann et al. (26)], there is ample cause for concern (i.e., that some terrestrial regions are experiencing faunal subtractions of 10% or more of their insects per decade).

That’s a lot. Some also find the speed of the decline alarming. From LeMonde, “Neither the magnitude nor the speed of the collapse of insects were anticipated by scientists” (2023)

Neither the magnitude, nor the speed, nor the systemic nature of the collapse of insects were anticipated by scientists. They are now measuring, stunned, the irreversible damage already committed.

In 2017, upon publication of the famous study by the Krefeld Entomological Society estimating at around 80% the drop in biomass of flying insects in some 60 German protected areas since the early 1990s, biologist Bernard Vaissière (INRAE), a specialist in wild bees, said to Le Monde: ‘If I had been told that 10 years ago, I wouldn’t have believed it at all.’ The other estimates that are accumulating and which largely corroborate this figure, still cause a sort of stupor among many specialists.

To be fair, insect decline studies all tend to have the same sort of weaknesses. For example, most insects have not been classified. Nor is there agreement on the numbers generally. From Friends of the Earth, “Insect Atlas“:

Compared to plants, mammals, birds and fish, insects are little researched. Only a small fraction has even been classified. Particularly little research has been done on the long-term occurrence and population dynamics of insects outside Europe and the US. Scientists agree that several well-studied species, such as monarch butterflies, some groups of moths and butterflies, and some species of bees and beetles are in decline – especially in Western Europe and North America. There is also consensus that insect biodiversity is decreasing in many parts of the world, while the numbers and biomass of the animals vary greatly depending on the region, climate change and land use, as well as the adaptability of each species. There is no scientifically confirmed figure for the global decline in insects. A first review by the University of Sydney in 2018 compiled information from research studies in various regions. It found that the populations of 41 percent of species are in decline, and one-third of all insect species are threatened by extinction. While cautioning that the available evidence is relatively thin, the researchers estimated that total insect biomass is declining by 2.5 percent a year.

Further, most studies are geographically limited (though not the reviews). From PNAS once more:

An important limitation of assessments based on long-term monitoring data are that they come from locations that have remained largely intact for the duration of the study and do not directly reflect population losses caused by the degradation or elimination of a specific monitoring site (although effects can be measured in a metapopulation context if the number of years sampled is sufficient in remaining sites). For example, butterfly censusing sites that have been lost to agriculture, urban development, or exotic plant invasions would not meet inclusion criteria for a study aimed at calculating long-term rates of decline. Surely, the greatest threat of the Anthropocene is exactly this: the incremental loss of populations due to human activities. Such subtractions commonly go uncounted in multidecadal studies

Finally, the field itself seems not to have the manpower to take on the job of measuring insect design (let alone teasing out causality). From the National Wildlife Federation, “Are Entomologists as Endangered as the Insects They Study?” (2024):

Scientists who identify, classify and study insects and the ecosystems they inhabit are essential to preventing the loss of the insect species that humans and all other living things depend on. They are also of critical importance for detecting and controlling diseases carried by ticks, mosquitoes and other invertebrates that can bring humans and other animals harm…. But Droege and other insect taxonomists like him are in short supply, especially when compared to the escalating need and the number of species still unknown to science…. Dwindling funds have fueled the taxonomist shortage. Over the past few decades, research funders like the National Science Foundation (NSF) and the National Institutes of Health (NIH) have shifted their priorities from “old-fashioned” descriptive sciences like taxonomy to cutting-edge fields like molecular biology, with researchers and students adjusting their career trajectories accordingly. And as an older generation of classically trained natural historians approaches retirement, their slots at universities are remaining unfilled. ‘We’re rapidly losing the expertise we need in quite a diversity of areas,” says Lynn Kimsey, professor of entomology and director of the Bohart Museum of Entomology at the University of California, Davis. ‘The driving force in universities is funding, and almost all the funding out of agencies like NSF and NIH is directed at DNA.’ Her own department offers one example. “At one point we had three taxonomists: one working on ants, one working on spiders and one working on stinging wasps,” she says. “Within five years, two of the three will be gone, and they won’t be replaced. And I’m seeing that at universities across the country.”

So not only are the studies we have underpowered with respect to the scale of the problem, we might not even have the scientific capacity to do better.[2]

Perhaps, in the end, the best proof is bugsplat — or lack thereof. BBC, “Bug splat survey shows decline in insect numbers“:

Since the first reference survey in 2004, an analysis of records from nearly 26,500 journeys across the UK shows a continuing decrease in bug splats.

The number in 2023 saw a 78% drop nationwide.

(Wikipedia, more gracefully, titles its page on this topic “Windshield Phenomenon.”) A bugsplat sample seems to me to be just as sound a method as the “vacuum backpack” used to sample Sussex insects, in the first study I cited. So by that measure, insect decline is significant.

Most agree on the causes of insect decline. Science Daily, “The reasons why insect numbers are decreasing” (2023) summarizes the consensus view[2]:

Together with forest entomologist Professor Martin Gossner of the Swiss Federal Institute for Forest, Snow and Landscape Research (WSL) and biologist Dr. Nadja Simons of TU Darmstadt, [Dr. Florian Menzel from the Institute of Organismic and Molecular Evolution at Johannes Gutenberg University Mainz] contacted international researchers in order to collate the information they could provide on insect declines and to stimulate new studies on the subject.

“In view of the results available to us, we learned that not just land-use intensification, global warming, and the escalating dispersal of invasive species are the main drivers of the global disappearance of insects, but also that these drivers interact with each other,” added Menzel. For example, ecosystems deteriorated by humans are more susceptible to climate change and so are their insect communities. Added to this, invasive species can establish easier in habitats damaged by human land-use and displace the native species.

Most also agree on the effects of insect decline. There’s a good deal of attention paid to pollinators. From CNN, “Parts of the world are heading toward an insect apocalypse, study suggests” (2022):

“Three quarters of our crops depend on insect pollinators,” Dave Goulson, a professor of biology at the University of Sussex in the UK, previously told CNN. “Crops will begin to fail. We won’t have things like strawberries.

“We can’t feed 7.5 billion people without insects.”

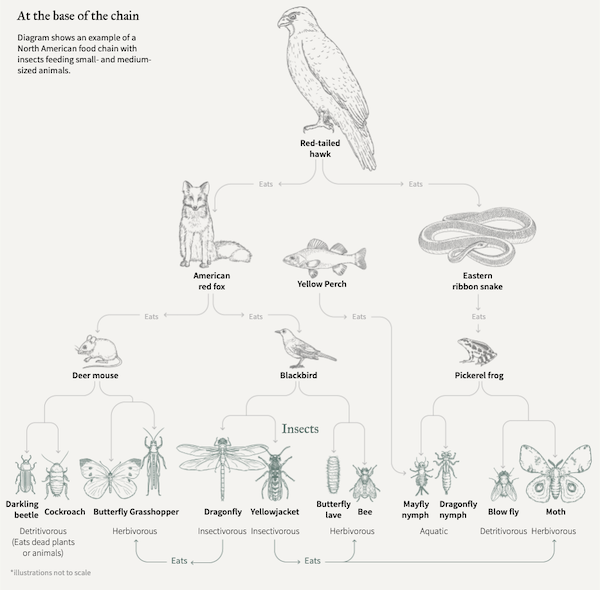

However, I think food chain issues generally could be even more important. From Reuters, “The collapse of insects” (2022) provides this handy diagram:

What happens when the species at the bottom of the food chain collapse out from under the species at the top?

The World Economic Forum published this opinion: “5 reasons why eating insects could reduce climate change” (2022):

We’ve been conditioned to think of animals and plants as our primary sources of proteins, namely meat, dairy and eggs or tofu, beans and nuts, but there’s an unsung category of sustainable and nutritious protein that has yet to widely catch on: insects.

Before you say “yuck,” hear us out.

(NPR, in its debunking of the idea that “The ruling class really, really wants us to eat bugs” omits it, oddly.) It would be amusing of this idea failed because there were no bugs to eat.

But what to do? From Princeton University Press, “Insect apocalypse” (2023):

Some solutions are obvious. Ban the worst of the insect poisons and limit the use of others. Unfortunately, most of these are manufactured by just a few giant companies who, through their immense wealth, have the ear of politicians and lawmakers. We also need to de-intensify farming to create space for insects along with other animals and plants. This could be achieved through reshaping farming subsidies, but this too is painfully slow to filter into the minds of political leaders.

And then, of course, climate change. But we can also consider helping the insects by land use changes, not such a heavy lift. From Nature, “Agriculture and climate change are reshaping insect biodiversity worldwide” (2022):

A high availability of nearby natural habitat often mitigates reductions in insect abundance and richness associated with agricultural land use and substantial climate warming but only in low-intensity agricultural systems. In such systems, in which high levels (75% cover) of natural habitat are available, abundance and richness were reduced by 7% and 5%, respectively, compared with reductions of 63% and 61% in places where less natural habitat is present (25% cover). Our results show that insect biodiversity will probably benefit from mitigating climate change, preserving natural habitat within landscapes and reducing the intensity of agriculture.

We can also help the insects by, as it were, brightening the corners where they are. From EurekAlert, “Monarch butterflies need help, and a little bit of milkweed goes a long way“:

Research shows that planting milkweed in home gardens can add significant monarch habitat to the landscape. In a new study in the journal Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution, researchers and community scientists monitored urban milkweed plants for butterfly eggs to learn what makes these city gardens more hospitable to monarchs. They found that even tiny city gardens attracted monarchs and became a home to caterpillars.

(Alert reader sc is a milkweed maven; see here.) And of course it’s always possible to plant flowers:

At the beginning of June, we planted sunflowers and a strip of annuals in the top field at #YewView. It’s looking mighty lovely today and the most insects I’ve seen in one place, this summer! pic.twitter.com/fwPlrJEebh

— WildlifeKate (@katemacrae) August 5, 2024

I know all these efforts are small, individual efforts. But if we think of climate change as a great fire, we can see that some of the seeds that we, as individuals, plant will survive and grow when we are through the evolutionary chokepoint and the fire has burnt itself out (albeit in a different world from the one we now live in).

For a coming post, I’ll see if there are more muscular and systemic efforts that can be taken (for example, classifying some insects as endangered species; curbing insecticide use at the municipal level; getting HOAs to surrender their lawn fetish). However, we (for some definition of “we”) would have to act quickly and from partial knowledge. But for now, we can do lots of these small things.

NOTES

[1] The same seems to be true of medical entomologists. Recently, a Japanese scientists discovered an insect vector for H5N1 (the blowfly). It would be a shame of we lost that capability.

[2] There are also particular causes within these general causes, like the effect of climate on insect digestive systems and phenology (the timing of various larval stages and emergence of flying adults, dams, and streetlights making leaves tougher. Also, generalists (cockroaches) tend to thrive, and specialists (monarch butterflies) not.