Subterranean pools of salty water may be commonplace on Jupiter’s moon, Europa, according to researchers who believe the sites could be promising spots to search for signs of life beyond Earth.

Evidence for the shallow pools, not far beneath the frozen surface of the Jovian moon, emerged when scientists noticed that giant parallel ridges stretching for hundreds of miles on Europa were strikingly similar to surface features discovered on the Greenland ice sheet.

If the extensive ice ridges that crisscross Europa formed in a similar way to those in Greenland, then pockets of subsurface water may be ubiquitous on the body and help circulate chemicals necessary for life from the icy shell down to the salty ocean that lurks far beneath.

“Liquid water near to the surface of the ice shell is a really provocative and promising place to imagine life having a shot,” said Dustin Schroeder, an associate professor of geophysics at Stanford University. “The idea that we could find a signature that would suggest a promising pocket of water like this might exist, I think, is very exciting.”

At 2,000 miles wide, Europa is slightly smaller than Earth’s moon. It became a leading contender in the search for life elsewhere when observations from ground-based telescopes and passing space probes found evidence of a deep ocean 10 to 15 miles beneath its icy surface.

Europa’s ocean is estimated at 40 to 100 miles deep, so even though it is one-quarter the width of Earth, it may hold twice as much water as all of Earth’s oceans combined.

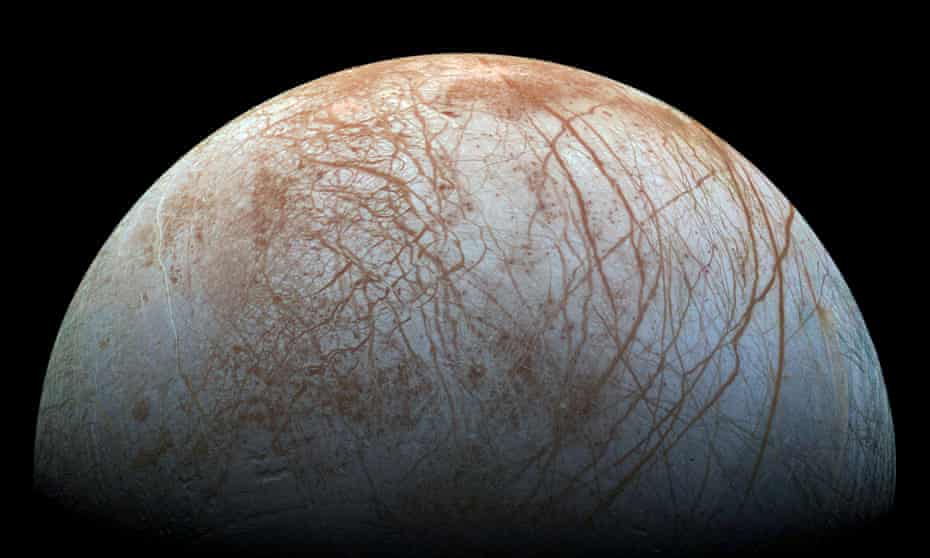

For all that is known about Europa, images of the frigid body have thrown up longstanding mysteries. One is the presence of vast double ridges that cover the surface like scars. The ridges can reach up to 300 metres (1,000ft) high and are separated by valleys half a mile wide.

The Stanford team’s insight was sparked by an academic presentation about Europa that mentioned the curious double ridges. Pictures of the features reminded the scientists of a much smaller double ridge they had noticed in north-west Greenland. Armed with radar and other observations of the Greenland ridges, they set about understanding how they formed.

“On the Greenland ice sheet there is this little double ridge feature that looks almost exactly like the ones we see on the surface of Jupiter’s moon Europa,” said Riley Culberg, a PhD candidate and geophysicist at Stanford. “And the reason it’s exciting to have this analogue feature in Greenland is that we’ve been trying to figure out what makes double ridges on Europa for about 20 years.”

Writing in Nature Communications, the researchers describe how Greenland’s double ice ridges, which are about 50 times smaller than those on Europa, formed when shallow pools of subsurface water froze and fractured the surface time and time again, steadily driving up the twin ridges. “It’s like when you put a can of soda in the freezer and it explodes. It’s that kind of pressure that pushes up the ridges on the surface,” said Culberg.

In Greenland, water drains into the underground pockets from surface lakes, but on Europa the scientists suspect liquid water is forced up towards the surface from the underlying ocean through fractures in the ice shell.

This movement of water could help circulate chemicals necessary for life down into Europa’s ocean, they add.

Michael Manga, a professor of earth and planetary science at the University of California, Berkeley, who was not involved in the research, said it was “plausible” for Europa’s ridges to form by water being squeezed upwards.

But questions remain. “I do wonder why the features are so much smaller on Earth,” he said. While Earth’s stronger gravity could explain why the ridges are lower here than on Europa, it is unclear why the valleys between them are narrower too.

Nasa’s Europa Clipper mission, due to launch in 2024, is expected to shed light on how the double ridges formed when it performs detailed reconnaissance of Jupiter’s moon and investigates whether it harbours conditions suitable for life.