Yves here. The Trump tariff blowtorch is now whacking the Treasury market. Even before this massive own goal, Trump was complaining about the Fed having interest rates that in his mind were too high was bad for business and (somehow) making inflation worse. Some commentators have argued that an (the?) objective of the tariffs was to lower interest rates, particularly on Treasuries, so as to lower the interest cost burden. That’s proving to be a backfire too. See the banner headline at the Wall Street Journal as of 5:30 AM EDT:

The story explains that the Treasury market is about to face new fundings at those longer maturitiees:

For bond investors, the sharp rise in yields is uncomfortably similar to a brief selloff that occurred at the depth of the Covid meltdown, when traders sold whatever they could to raise cash. Further increases in Treasury yields could add to pressure on economies already hit by rising prices and slowing trade due to tariffs.

Investors say there is broad nervousness about holding longer-term Treasurys ahead of government auctions of 10-year notes Wednesday and 30-year bonds Thursday. That anxiety contributed to a global stock selloff overnight, with Japanese stocks falling 3.9% and European stocks down 2% in Europe’s morning. U.S. stock futures were volatile and recently stood modestly lower.

Japan’s top currency diplomat pledged to ensure stability in the global financial system, saying Tokyo will coordinate with other nations on U.S. trade policy changes.

Keep in mind that a reason for Japan and other countries to help prop up Treasuries is to lower the value of their currencies. Buying Treasuries for Japan means buying dollars and selling yen. China, which runs a dirty float, lowered the value of the renminbi a bit when it announced its retaliatory 34% tariffs. Japan, by contrast, has seen the yen rise as an alternative safe haven. It will want to contain and better yet somewhat reverse that increase so as not to have its price competitiveness worsen. Recall that competitive devaluations were a feature of the Great Depression.

I was in Japan during the 1987 crash, when I worked for Sumitomo Bank, then the largest by market cap. At first, the sentiment was akin to watching someone else’s house burn. Then it shifted to the concern that one’s own house might catch on fire. Treasuries started getting wobbly. The Fed called the Bank of Japan and told it to buy Treasuries. The Bank of Japan called the Japanese “city banks” (the equivalent of what were called money center banks in the US at the time) and told them to start purchasing.

The Financial Times also made the Treasury bond selloff its lead entry:

From its account:

Ed Yardeni of Yardeni Associates said the sell-off in Treasuries, typically a haven for investors during periods of market stress, was signalling that the “Trump administration may be playing with liquid nitro”.

Investors and economists have warned that Trump’s tariffs have increased the risk of a recession in the US, the world’s biggest economy, as well as a new bout of inflation.

As investors raced to price in slower global growth, oil prices extended their slump. Brent crude futures, the international benchmark, dropped to a four-year low of $60.13 a barrel.

Keep in mind that Yardeni is close to a permabull.

It’s not as if Treasuries are the only pain point :

:

Adam Tooze noted earlier this week that where Treasury prices would settle out would be the result of the interplay between investors with two different theories of the tariffs case:

Treasuries are a general-purpose safe haven. Investors who are selling their shares, driving stock market prices down, have to park their cash somewhere. The obvious place are US Treasuries. In the “normal” course of a stock market correction, we would expect to see bond prices going up as stock prices go down, as investors shuffle from one to the other. As bond prices go up, the yield (the effective interest rate) goes down. This tends to lower interest rates and ease pressure on businesses. This is the see-sawing, balancing effect of markets operating across assets. Again, it is painful, but it is good news. People take losses. But it suggests that the financial system is still working. As Katie Martin commented in the FT in the last few hours, this is the one to watch.

As the Wall Street Journal commented 10 minutes ago (I kid you not), the market is hard to read right now because longer term bond yields have to price in inflation, and Trump’s tariffs are clearly terrible for inflation. So right now we have safe-haven demand driving Treasury prices up (causing yields to come down) and inflation fear driving Treasury demand down (causing yields to go up). All of us are trying to read through the fog.

Now that does mean that the post by Murphy below is overegging the pudding a tad. Given Trump’s doggedness about tariffs and their baked-in inflationary impact (at least until the eventual depression kills demand stone cold dead) will make investors particularly leery of holding longer-maturity bonds. But the general idea still applies.

As an aside, criminal negligence by the Treasury in the Obama, Trump 1.0, and Biden eras plays a meaningful role in the freakout over Federal interest costs now. The Treasury should have done as much funding on the long end of the yield curve as humanly possible during the ZIRP era. Instead it borrowed in short maturities. Admittedly, longer-dated debt would eventually roll off and have to be refunded at higher cost, but that process would have taken time and blunted the impact of rate increases.

By Richard Murphy, Professor of Accounting Practice at Sheffield University Management School and a director of the Corporate Accountability Network. Originally published at Funding the Future

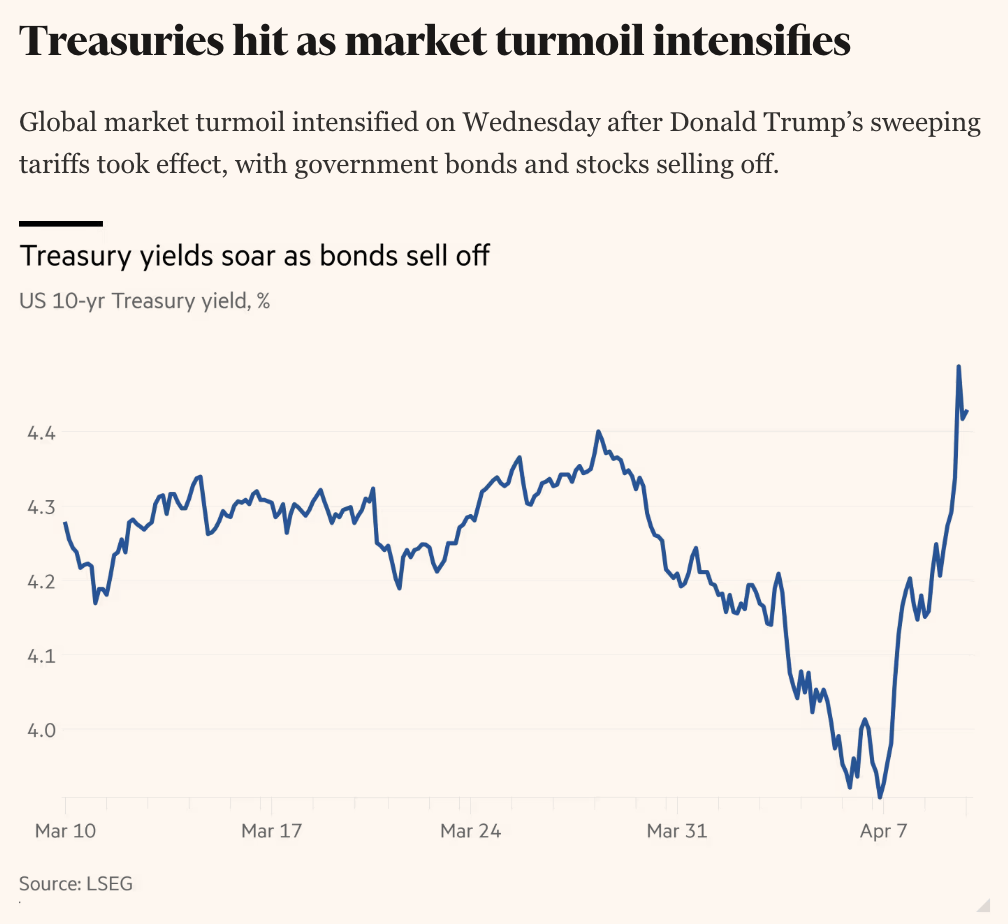

This chart has been published by the FT in the last few minutes:

The world has reacted to Trump’s deliberate act of massive risk creation by sending the message that it will not buy US debt. The result is that the price of that debt is falling, and so the effective interest rate on it is rising very rapidly.

This is the exact opposite of what Trump says he wants. He says he wants the US interest rate to fall by a lot. In bond markets, you cannot achieve that by alienating the people who might buy your debt, and that is what he is doing.

What’s the fallout?

First, as I note this morning, he might utterly overturn those markets, and in effect default on large parts of US debt by demanding that those holding it swap that debt for long-term or perpetual debt at very low rates.

Secondly, do not rule out that he will do large-scale quantitative easing, with all the downsides that go with that.

Third, do not presume that we will escape from this unscathed. Where US interest rates go tends to suggest where the rest of the world will move. There is, then, very bad news in all this.

Fourth, without coordinated action to work around Trump, there is no way the rest of the world can manage this fallout. It either combines against Trump or is divided and ruled by him, with disastrous consequences.

Fifth, do not expect wealthy America to be happy about any of this. They will react. But they may not react in a way that we think desirable. Their tendency towards autocracy is now well known.

Sixth, then, freedom has a fight on its hands. That chart implies an ugliness is coming our way.