Yves here. This post discusses the widespread assumption that if Trump moves forward with his plan to impose across-the-board tariffs on America’s three biggest trade partners, that will be inflationary and the Fed will be forced to respond via increasing interest rates. This article contends that higher rates make sense only if US trade partners do not (one assumes meaningfully) retaliate. Easing may wind up being in order if tariffs to reduce US growth.

By Paul Bergin, Professor of Economics University of California, Davis and Giancarlo Corsetti, Pierre Werner Chair and Joint Professor, Department of Economics and Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies European University Institute. Originally published at VoxEU

Donald Trump’s victory in the recent US presidential election has re-ignited a debate over the macroeconomic effects of tariffs and the appropriate monetary policy response. This column argues that even if there is broad agreement that new tariffs would likely be inflationary for the US, the current situation presents various factors which suggest that it might be optimal for policy to focus more on the inefficient fall in output.

The results of the recent US presidential election re-ignited a debate over the macroeconomic effects of tariffs, and the appropriate monetary policy response to a trade war. During the first Trump administration, US tariffs on Chinese exports rose seven-fold between 2018 and 2020, and they remained high under the Biden administration. More to the point, global political trends point to a significant weakening of global consensus regarding free trade and herald a new environment in which central banks may face this new type of shock with increasing frequency.

Much of recent research on the macroeconomic effects of trade policy shocks has been conducted in the context of real trade models, or in empirical exercises without consideration of monetary policy. 1 But the consequences of trade frictions obviously challenge central banks: how should they respond to a backwards step in the progress towards increasing trade integration, with potentially significant effects on inflation, economic activity, external balances, and real exchange rates? In a recent paper (Bergin and Corsetti 2023), we study the optimal monetary policy responses to tariff shocks of various types. In this column, we update the analysis and distill lessons appropriate to the current situation.

In our paper, we study the optimal monetary policy responses to tariff shocks using a standard workhorse open-economy New Keynesian (sticky-price) model augmented with international value chains in production, i.e. imported goods are used in the production of domestic goods and exports. This implies that raising tariff protection of domestic exporters raises the cost of production for domestic firms. Throughout our analysis, we assume a share of imported inputs in production close to estimates based on the US input–output tables for 2011 (but we also verify our main conclusions varying this share). Our main analysis assumes substantial pass through of tariffs to consumer prices, but we also demonstrate robustness of our main results to enriching the model with a distribution sector that limits pass-through. Finally, we posit that monetary authorities do not take advantage of cross-border spillovers to pursue beggar-thy-neighbour policies, i.e. we rule out opportunistic manipulation of the exchange rate. 2

To sum up our main message: even if there is broad agreement that new Trump tariffs will likely be inflationary for the US, it is far from obvious that the optimal response of monetary policy to these tariffs should focus on fighting these inflationary effects via monetary contraction. Tariff shocks combine elements of both demand and supply disturbances, and monetary policy is bound to face a difficult trade-off between moderating inflation and supporting economic activity; in fact, a reasonable calibration of our model indicates that the optimal monetary response to such a scenario may well involve monetary expansion. Our analysis underscores that, while the optimal monetary response to tariffs depends on several factors, a key role is played by (i) the likelihood that the tariffs are reciprocated in a trade war, (ii) the degree of reliance of domestic production on imported intermediates, and (iii) the special role of the US dollar as the dominant currency for invoicing international trade. We discuss different cases in turn.

The Case for Monetary Tightening: Unilateral tariffs Without Retaliation

Let us consider first the rationale for monetary tightening. This would be clear in a scenario in which the US unilaterally imposes a tariff on domestic purchases of foreign goods to boost demand for domestic goods, causing inflation in the price paid by domestic consumers and producers using imported inputs.

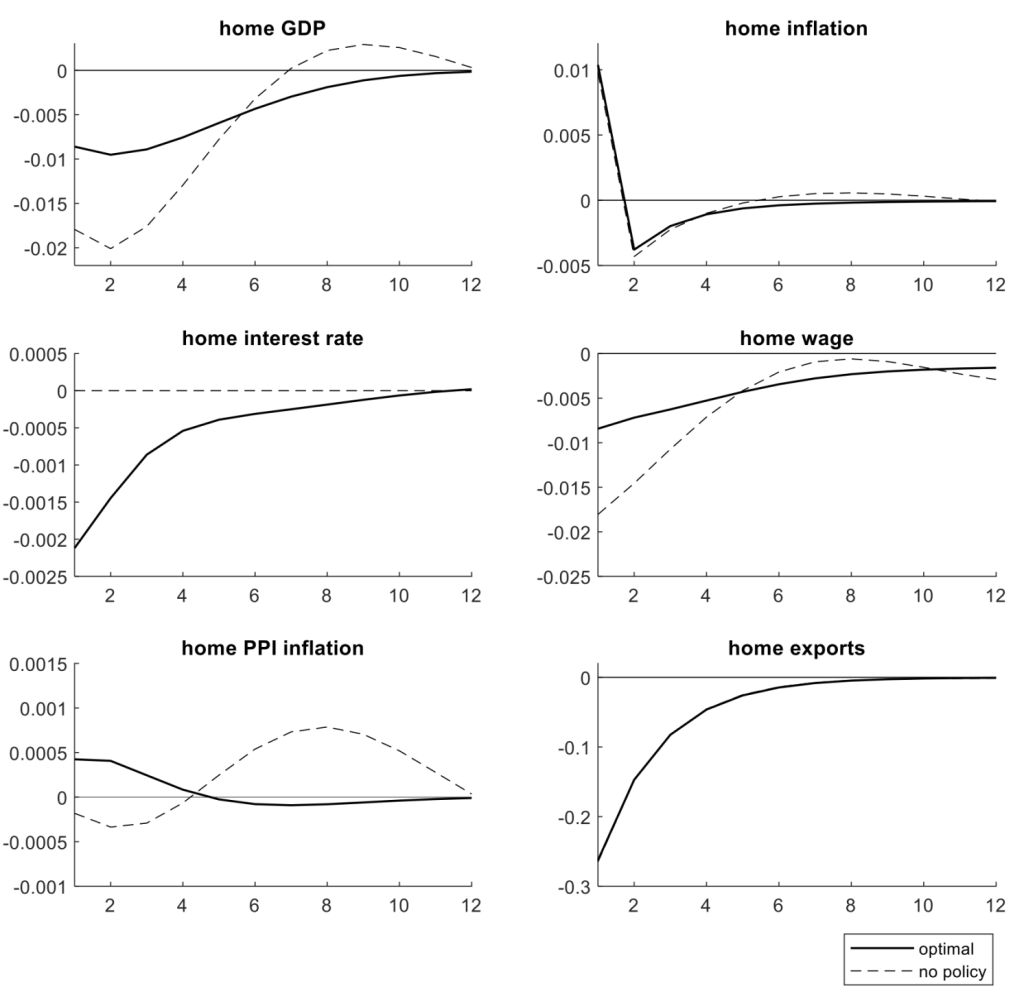

In Figure 1, we use our model to trace the effects of a unilateral tariff shock. The dashed lines trace the effect of such a shock over time while holding policy rates constant: GDP and inflation rise in the US, but they move in the opposite direction in the US’ trade partner (the foreign country). At the ongoing exchange rate, the US trade balance turns into a surplus.

Figure 1 Unilateral tariff on home imports

Note: Vertical axis is percent deviation (0.01=1%) from steady state levels. Horizontal axis is time (in quarters).

Looking at these baseline results, a policy of monetary contraction at home (US) can be motivated by a need to moderate inflation – corresponding to monetary expansion abroad to moderate deflation. But a further motivation can be found in the fact that the divergence in the home and foreign policy stance works to appreciate the home currency, which can serve to lower the effective price of foreign goods that home consumers see, and thus partly offset the distortionary effect of the tariffs on relative prices.

These considerations underlie the behaviour of macro variables under the optimal policy, traced as a solid line in the figure. The US monetary authorities curb inflation, which in our case serves also to moderate the domestic rise in output. The fall in demand and the dollar appreciation reduce the trade surplus somewhat. Abroad, monetary authorities support activity at the cost of inflation, contributing to correcting in part the international relative price of goods distorted by the tariff. 3

As we show in our paper, the conclusions so far remain valid also when the degree of exchange rate pass through is low across all borders, i.e. prices are sticky in the currency of the export destination country. A low pass through reduces the effect of currency depreciation on relative prices, and monetary policy cannot rely on currency depreciation to redirect global demand towards own traded goods. Yet, in response to a unilateral tariff, the optimal stance is still contractionary at home and expansionary abroad.

The Case for Monetary Expansions: Trade Wars

Where our paper is more innovative is in showing that the optimal policy is generally expansionary in the case of a symmetric tariff war – say, if the foreign country retaliates with equivalent tariffs on imports of US goods. In this case, the US experiences not only higher inflation but also a drop in output, driven by the fall in global demand induced by the hike in trade costs. Trade wars present policymakers with a choice between moderating headline inflation with a monetary contraction, or instead moderating its negative impact on output and employment with a monetary expansion.

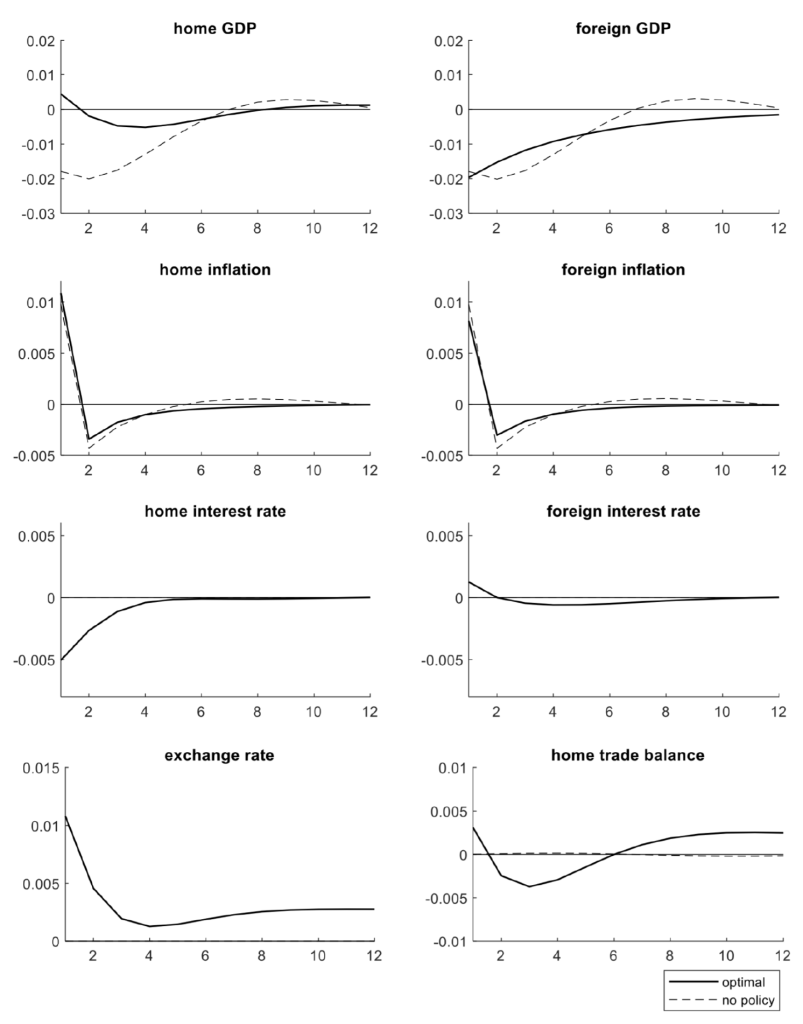

The trade-off confronting central banks is illustrated by the dashed lines in Figure 2, drawn for a symmetric war, under the assumptions that the pass through of the exchange rate on border prices is very high. The contractionary effects of the tariff war include a deep drop in gross exports worldwide. Inflation spikes, while output falls.

Figure 2 Symmetric tariff

Note: Vertical axis is percent deviation (0.01=1%) from steady state levels. Horizontal axis is time (in quarters).

A trade-off between inflation and unemployment is obviously not unfamiliar to policymakers. If it were generated by a standard supply shock – say, a fall in productivity – standard macro models would suggest optimal policy would choose monetary contraction to stabilise inflation. However, as stressed in our analysis, tariffs are quite different from a standard productivity shock, in that they combine elements of supply shocks with demand shocks, and the optimal policy consequently tends to be quite different. One way to see this is that while a tariff war raises the average price of all consumption goods, including imports, the contraction in global demand tends to reduce the prices set by domestic firms. In other words, tariffs raise CPI inflation but tend to depress PPI inflation. In a retaliatory trade war, it is optimal to expand and stabilise PPI inflation despite the hike in CPI inflation hitting consumers. This is shown by the solid lines in Figure 2, drawn for one country (the conclusion applies symmetrically of course to all countries engaging in the trade war).

While we have demonstrated above that tariff shocks are quite different from productivity shocks, it is also important not to confuse tariff shocks with cost-push markup shocks. First, a home tariff shock only affects the prices of imported goods, while markup shocks are typically envisioned as affecting domestically produced goods. Second, the revenue generated by a tariff shock accrues to the importing country, while the profits from higher markups go to firms in the exporting country. Third, tariffs are imposed directly on the buyer, thus added on top of the price set by the exporter. Our model highlights the unique nature of tariff shocks relative to these other supply disturbances; even while monetary contraction is the optimal response to adverse productivity or markup shocks in the context of our model, monetary expansion is the optimal response to a tariff shock generating inflation.

Our analysis fully accounts for the fact that production in the US uses a high share of imported intermediate inputs, i.e. higher production costs amplify the supply-side implications of the tariff relative to the demand implications. Indeed, in our quantitative exercises, we find that the optimal response to a trade war becomes contractionary at a particularly high share of imported intermediate inputs in production. But based on input–output estimates of this share (and extensive robustness analysis in which we vary the share), we believe that our benchmark conclusion (prescribing an expansionary monetary stance) can be expected to be more relevant empirically.

The ‘Privilege’ of Issuing the Dominant Currency in International Trade

The US dollar has a special role as the dominant currency used in international trade of goods. It is well known that if the prices of imports in all countries are sticky in dollar units, the US (the dominant currency country) can rely to a much larger extent on monetary policy as a stabilisation tool. That is, it should be in a better position to redress the distortionary effects of the tariff shock on own output and employment, with relevant implications for the rest of the world.

Consider first a tariff war, depicted in Figure 3 (again, the dashed lines trace the no-policy scenario, the solid lines the optimal policy scenario). On impact, the war is a global contractionary shock. In the dominant currency country, the optimal monetary response is now relatively more expansionary, as the national monetary authorities can redress the lack of global demand without feeding the inflation of imported inputs at the border – imports in dollars move very little with a dollar depreciation. An expansion in the dominant-currency country is good news for the other country: it contains the fall in global demand and reduces imported inflation there (a dollar depreciation means that importers abroad pay a cheaper price in domestic currency at the border). Because of this, even if the tariffs hikes are perfectly symmetric, the other country is in a different position. Rather than matching the expansion in the US, it resorts to a mild upfront contraction to contain inflation. Note that, while GDP falls in both countries, it falls by less in the country issuing the dominant currency. The US dollar depreciates in this scenario.

Figure 3 Symmetric tariff, home issues the dominant currency in trade

Note: Vertical axis is percent deviation (0.01=1%) from steady state levels. Horizontal axis is time (in quarters).

As we discussed above, in the case that the tariff is unilaterally imposed by the dominant currency country, the global demand for exports by this country does not suffer the effects of a retaliatory tariff. Hence, inflation becomes a more pressing concern for monetary authorities – the optimal stance is contractionary. The contraction can now be stronger, because the dollar appreciation has more muted crowding-out effects on US goods in the international market. The stronger contraction has global repercussions. Abroad the optimal stance becomes expansionary – to prompt domestic demand vis-à-vis falling exports to the US – tolerating inflation and exacerbating currency depreciation. The US dollar appreciates sharply in this scenario.

Conclusions

Tariff shocks may present policymakers with a particularly difficult choice between moderating inflation and the output gap. Several factors of the current situation suggest that, even while tariffs are likely to be inflationary, it might be optimal for policy to focus more on the inefficient fall in output. These factors include the likelihood that US tariffs could be reciprocated in a tariff war, the fact that current tariff threats seem centred more on final consumption goods rather than intermediate inputs in domestic production, and the fact that the US dollar has an asymmetric position in world trade as a dominant currency.

See original post for references