Yves here. This post contains informative details on the ongoing row between Judge James Boasberg and the Department of Justice, which defied his order in a deportation of Venezuelans for the planes containing the detainees en route to El Salvador return to the US. The lawlessness of this Administration is stunning. First, as Judge Napolitano, who was a judge, has pointed out, the notion that Boasberg’s order was no longer operative because (per the unverified assertion) the planes were in international air space, is laughable. The entire chain of command, along with the pilots and crew on the planes, were under US jurisdiction. Second, the idea that a verbal order somehow does not count is also a joke.

Trump being Trump, he has attempted to escalate by threatening Judge Boasberg with impeachment. An obliging stooge in the House, Brandon Gill, has filed articles of impeachment. That comes after Chief Justice John Roberts having cleared his throat (Reuters called it a rebuke) after Trump made that threat, to stress that the way to handle unfavorable decisions is not to seek removal of the judge but to appeal.

NBC News provided an update of the duel between the Boasberg and the DoJ after the time of the filings discussed below. Sadly it appears the judge has fallen for the DoJ position on jurisdiction, although it is possible he is casting his net wider than necessary (as in flight details) to catch acts of perjury:

In his ruling Monday, Boasberg said that if the Justice Department “takes the position that it will not provide” more details about the flights “under any circumstances, it must support such position, including with classified authorities if necessary,” and that it could file those arguments under seal, if necessary.

The Justice Department declined to do so, noting it has appealed Boasberg’s earlier ruling. “If, however, the Court nevertheless orders the Government to provide additional details, the Court should do so through an in camera and ex parte declaration, in order to protect sensitive information bearing on foreign relations,” the filing said.

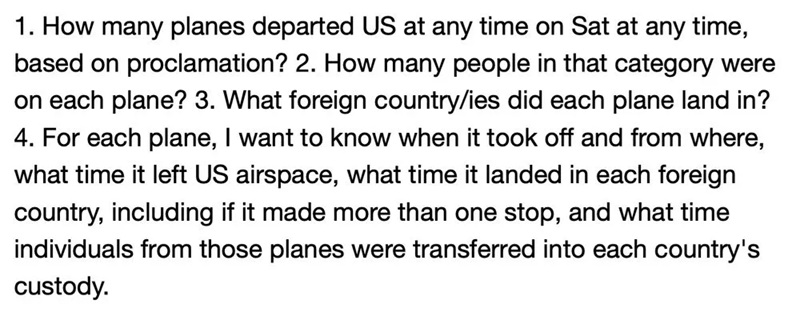

Boasberg did just that a short time later, directing the government to provide him with “the following details regarding each of the two flights leaving U.S. airspace before 7:25 p.m. on March 15, 2025: 1) What time did the plane take off from U.S. soil and from where? 2) What time did it leave U.S. airspace? 3) What time did it land in which foreign country (including if it made more than one stop)? 4) What time were individuals subject solely to the Proclamation transferred out of U.S. custody? and 5) How many people were aboard solely on the basis of the Proclamation?”

Let us not forget that anyone on US soil has due process rights per Article 5 and 14 of the Constitution. These Venezuelans were merely charged. They have the right to respond to accusations and have the evidence on both sides weighed by a finder of fact, as in a judge or jury. But this Administration wants to make itself the decider of all rights in the US.

By Angry Bear. Originally published at Angry Bear

As Joyce Vance states, “that’s not how it works. If a judge is considering whether a party, especially the government, is in contempt of an order, the judge gets whatever information they need. Otherwise, it is contempt.”

Deportations: It’s not where it starts, it’s where it ends, Civil Discourse

Just ahead of the hearing scheduled for 5 p.m. Eastern in the case we discussed last night, the Justice Department asked Judge James Boasberg to vacate the order setting the hearing. The government didn’t want to have to show up. Their reason? They wrote they weren’t in violation of the two temporary restraining orders (TROs) he issued over the weekend, the first for the five named plaintiffs in the case and the second for the remainder of the group subject to deportation. DOJ also told the Judge that “the government is not prepared to disclose any further national security or operational security details.”

In my experience, that’s not how it works. If a judge is considering whether a party, especially the government, is in contempt of an order, the judge gets whatever information they need. Otherwise, contempt.

But that’s not how the government played it today. When Judge Boasberg indicated he would hold the hearing nonetheless, they appealed—sort of.

The government had already taken an appeal of the two temporary restraining orders the court entered. Today, they filed what’s known as a Rule 28(j) letter with the Court of Appeals in that case. This rule provides parties with a vehicle for letting the court know about new authority, for instance a new Supreme Court case that is handed down after they brief or argue their case. Instead, they used it to demand that the hearing be canceled and a new judge be assigned to their case.

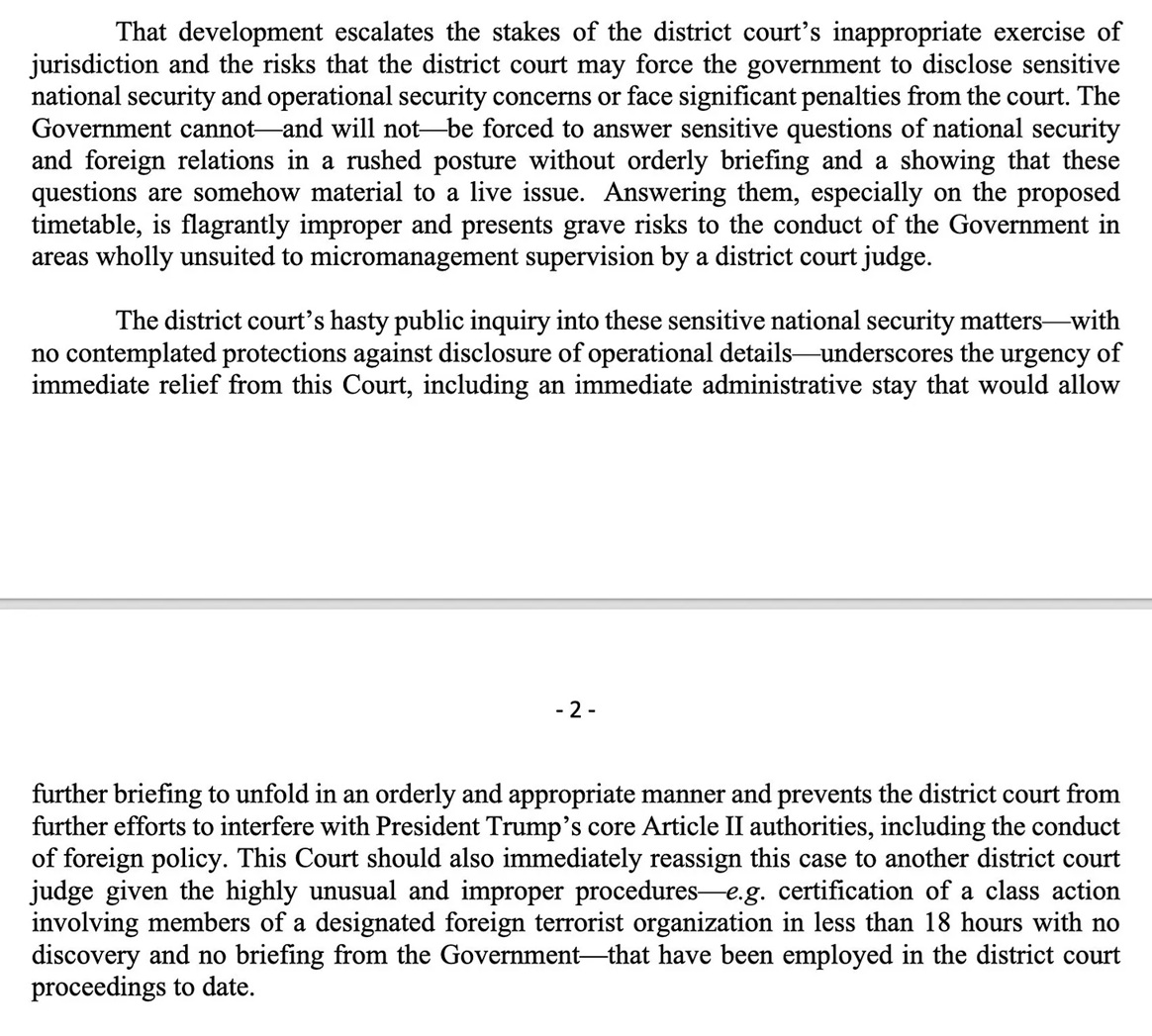

It’s not really a motion, so there is nothing for the Court of Appeals to grant (or deny) here. Not exactly stellar lawyering. The government argued that “the district court may force the government to disclose sensitive national security and operational security concerns or face significant penalties from the court. The Government cannot—and will not—be forced to answer sensitive questions of national security and foreign relations.”

Let’s take that apart. For one thing, the government and its foreign ally, El Salvador’s president, have been bragging about these deportations all over social media, including with video of detainees being forced off the planes in stress positions. The flight information is public. So it’s difficult to discern what’s sensitive here. In any event, courts, as Judge Boasberg pointed out during the hearing, are capable of taking in sensitive information out of the public eye and even classified information in SCIFs, something that happens frequently, especially in Washington, D.C. The only real takeaway from the government’s arguments on paper and in the hearing was that they really didn’t want to be there.

Pro lawyering tip: Telling a judge the questions he wants answered are “flagrantly improper” when contempt allegations are on the table is a strategy that will make even an even-keeled judge like Judge Boasberg still more intent on getting to the truth.

This letter from DOJ to the court is a clear expression of the administration’s mistaken belief that the president is more powerful than the other branches of government rather than a co-equal sharer of power as envisioned by the Founding Fathers. This administration continues to say the quiet part out loud, and the quiet part is that Donald Trump wants total control—the government’s lawyer told the Judge today that Trump’s decisions, once the plane was outside of U.S. territory, could not be reviewed by a court. Trump wants to be a democratically elected president who owes obedience to the law and service to the people in name only.

When the Judge took the bench, he confirmed, in a deceptively mild manner, that the Court of Appeals hadn’t granted the request to suspend the hearing. Lee Gelernt, the head of the ACLU’s Immigrants’ Rights Project, argued for the plaintiffs. Abhishek Kambli, a DOJ lawyer and member of the Federalist Society who was previously a high-ranking official in the Kansas attorney general’s office, represented the government. The Judge clarified the reason for the hearing—it wasn’t about the merits of the TROs he’d entered over the weekend. It was “solely for fact-finding about the government’s adherence with orders,” in other words, whether the government had violated them and should be held in contempt.

The Judge began to ask questions. First, he wanted to know whether the five named plaintiffs in the case were still in the United States. Kambli responded, “Yes, that’s what I’ve been told.” Perhaps it was just an expression, but in context it was hard to read it as anything other than a lawyer being careful to make clear that anything he said in court was based on what the client, here the United States of America, told him. That’s unusual for a government lawyer. If I’d had any doubts about the client’s candor, I wouldn’t have gone into court. But we’re now in an era where Justice Department lawyers are either Trump loyalists or forbidden by AG Bondi’s new policy from declining to sign motions or appear in court when directed to. So, the court gets, “that’s what I’ve been told.”

The Judge also had questions about the timeline and numbers of people involved. But when he asked how many planes departed Saturday carrying Venezuelans being deported under Trump’s proclamation, the response was, “those are operational issues and I’m not authorized to provide” that information. Kambli told the Judge, “I am authorized to say” that no flights took off after the written order issued by the court and that the timing of two flights plaintiffs had said they were concerned about had “no material bearing” on the situation. And that, Kambli apparently hoped, would be that. “That’s the only information I can give,” he said, citing national security and diplomatic concerns.

There were a few upshots. One was that it became clear that the government’s position was that it was entitled to ignore everything the Judge said in court on Saturday—he expressly told them to turn any planes in flight around—and was only bound by the written order he issued after the fact. When the government insisted it couldn’t share the requested information with the Judge, he pressed them on the law, insisting that they could based on his experience as a judge on the FISA court (as we mentioned last night), and finally pointed out that even in the exceptional case where the government could withhold information from the court, they still had to make a strong showing as to why that was justified. The government didn’t offer anything along those lines here.

With the appearance of a careful judge making his record before he disciplines a recalcitrant party, the Judge then gave the government until noon tomorrow to file answers to a series of questions he specified or explain why they weren’t providing answers.

Then came an interesting moment, the only time during the hearing where Judge Boasberg actually used the word contempt, where he asked Kambli two additional questions about when Trump signed the proclamation that allegedly triggered his ability to deport members of the Tren de Aragua gang and how many people subject to deportation were in the U.S. His lead-in to the questions was to say that they didn’t relate to contempt, confirming, of course, that the earlier questions did and that the government was at risk.

By the time the hearing was over and the government had its marching orders from the court, the arguments they were making were also clarified:

- They didn’t have to obey the court’s oral ruling.

- Even if they did, they had obeyed it because the planes were beyond U.S. airspace before the court ruled, so the Judge didn’t have jurisdiction over the planes.

The Judge made the same point we discussed last night: that if the government disagreed with the court’s order, it should have returned the detainees to the United States and appealed it. The government’s response was that because the president is the commander-in-chief and he can direct military forces, he has Article II powers under the Constitution that are not subject to judicial review. That meant, Kambli said, that they were free to ignore the court’s order and continue the flights.

That was where the hearing ended up. The Judge got in a parting shot, saying he would hear from the government tomorrow, Tuesday, by noon and that “I will memorialize this in a written order, since my oral orders apparently don’t carry much weight.”

All of this flies in the face the way government lawyers conduct themselves in court. The government complies with court orders, even ones it disagrees with, in both the letter and the spirit. Any challenges to them are made in court. It’s hard to overstate how much of a change this administration’s approach is, specifically when it comes to the level of (dis)respect shown for a judge’s order.

What shouldn’t get lost here is that this case also involves horrific human rights abuse. The Trump administration’s argument is that these are bad people. Some of them may be. But they have been put in custody in one of the worst prisons in the world at the expense of American taxpayers instead of simply being deported to their home country. They received no process; they have little recourse.

So, for instance, if a U.S. citizen were swept up in the arrests, they would have had no opportunity to establish they’d been wrongfully detained. The result would be not just deportation but imprisonment in a foreign country in harsh conditions if this is permitted to stand. No court has confirmed the government’s assertion that these detainees are all dangerous gang members. The process of using tattoos to determine gang membership, which the government used for at least some people, is far from precise, and people caught up in this have no chance to challenge the assessment. Trump asked for gang members, and ICE delivered.

This is where the Trump administration has started, but it’s likely not where they hope it will end. For many Americans, deporting violent gang members will sound like a good idea, constitutional niceties be damned. They are the perfect group of people for a government test case. As lawyers like to say, good facts make good law, and what better justification for questionable deportation than getting dangerous people out of the country.

But it’s important to understand that we protect everyone’s rights in this country, not just people we like. And it couldn’t be clearer why. It’s a steep slippery slope from the alleged gang members (no court has confirmed that designation) to a noted surgeon (the Boston case) and then onto others. If the law doesn’t apply, then the government is free to violate people’s rights at will. And when this case gets to the Supreme Court, as it will, if the administration wins, then it’s pretty much open season. Anything goes.

It is a bleak moment in history.