The Noboa government’s labelling of the drug cartels as “terrorist organisations” and “belligerent non-state actors” opens the door even wider to the possibility of US military support.

Ecuador’s new President Daniel Noboa, the 36-year old son of the country’s richest businessman, has been in office for just under two months and he has already declared war on the country’s criminal gangs. On Monday (Jan 8), he announced a state of emergency following riots in six prisons in which prison guards were taken hostage and the leaders of two of Ecuador’s largest drug cartels managed to escape. The next day (Jan 9), armed men stormed the TC television channel in Guayaquil and took staff hostage during a live broadcast.

Alina Manrique Cedeño, a journalist for the television channel, explained to the media that the gang members that took over the channel were very young and were taking orders over their cell phones. In her opinion, the gang wanted to send the public a message of terror during prime time on Ecuador’s most watched channel. On the same day, armed groups also entered universities and other public institutions amid widespread looting in Quito.

In response, Noboa declared an “internal armed conflict” against the country’s criminal gangs, labelling more than 20 of them as “terrorist organisations” and “belligerent non-state actors (Coincidentally, is what Republican lawmakers in the US have been calling for Mexican drug cartels to be labelled terrorist organisations in order to green light armed US intervention in Mexico).

Noboa ordered the deployment of the country’s armed forces onto the streets of Ecuador’s cities to assist the Police in combating the drug cartels and restore law and order in the crime-ravaged country. The order will initially be in force for 8 days, though that is likely to be extended.

If this story sounds familiar, it’s because we have seen the same script, with minor alterations, play out before, most recently in Mexico. In early 2007, Mexico’s then-President Felipe Calderon, also in his first months in office, declared total war on the drug cartels. Like Noboa, he had neither the resources, expertise or manpower to take on such a task. As in Ecuador today, Mexico’s armed forces, like the police, were drastically under-resourced and had already been compromised by the cartels. Here’s what happened next, as the war unleashed an unending cycle of chaos, violence and death:

As the violence in Ecuador escalates, the government of neighbouring Peru has declared a state of emergency on its northern border with Ecuador, and is even considering closing the border and sending troop reinforcements there. Mexico’s government has warned its citizens in Ecuador not to go out unless strictly necessary, and both the US and Chinese embassies in the country have cancelled appointments for consular matters at their headquarters in Guayaquil, the coastal city from where most of the drugs are shipped abroad and much of the gang violence is concentrated.

The Broader Picture

Noboa’s labelling of the drug cartels as “terrorist organisations” and “belligerent non-state actors” opens the door even wider to the prospect of military support and even direct intervention from the US armed forces, which has been on the cards for quite some time, as we first reported in June 2022. The Biden Administration is now offering to bolster its “cooperation” with Quito.

“We are willing to take concrete measures to improve our cooperation with the Government of Ecuador in its fight against violence,” National Security Council spokesman John Kirby said during the daily White House press conference on Wednesday. Kirby added that so far the Biden Administration has not held specific conversations with Noboa or his government, but is willing to discuss what Ecuador may need to address its crisis.

National Security Advisor, Jake Sullivan, tweeted the following message a little later:

We strongly condemn the recent criminal attacks by armed groups in Ecuador against private, public, & government institutions. We are committed to supporting Ecuadorians’ security & prosperity & bolstering cooperation w/partners to ensure the perpetrators are brought to justice.

— Jake Sullivan (@JakeSullivan46) January 10, 2024

Crucially, these words of support come just four months after Washington signed a hush-hush agreement with Ecuador’s outgoing President Guillermo Lasso to allow the entry of US troops onto Ecuadorian soil.

The US isn’t the only government talking about offering direct military support to Ecuador. In Argentina, the Milei government’s Minister of Security Patricia Bullrich has described the situation in the country as “a continental-wide issue” and has refused to rule out sending military aid, including troops, to Ecuador:

“We are willing to help them and, if necessary, send security forces. It is a continental issue, we have to protect ourselves from this.”

There is, I believe, a logic, however twisted and unoriginal, to all of this. As I reported in early October, the US is seeking to escalate its war on drugs in Latin America, as a pretext for trying to regain strategic dominance of its “backyard”, particularly the resource-rich regions. First, US Homeland Security Investigations signed an agreement with the Boluarte government in Peru to collaborate in transnational criminal investigations. Then, weeks later, a similar agreement was signed with Ecuador. Since then, the governments of both Andean countries have asked the US to develop a Plan Colombia-style initiative to help combat the drug cartels.

The US is also helping Guyana to “enhance” the security capabilities of its armed forces, including in the area of counter narcotics. That’s according to an official statement issued by the Guyanese government this week following a visit by the US Undersecretary of Defence for the Western Hemisphere, Daniel Erikson. As NC readers are well aware, Guyana is currently locked in a border standoff with its northern neighbour, Venezuela.

Erickson’s visit came just two weeks after the UK sent an offshore patrol vessel, the HMS Trent, to Guyanese waters in a gesture of solidarity with its former colony. The Foreign Minister of Venezuela, Yván Gil, said Wednesday that the visit of the senior US defence official threatens the stability of the Latin American and Caribbean region.

Meanwhile, in Argentina, Javier Milei’s government has proposed granting the executive branch the power to “authorise the entry into the country of troops and equipment of foreign armed forces for the purpose of exercises, training or protocol activities” as well as the deployment of Argentine forces abroad. Until now, such movements have needed the approval of Congress. The measure, together with 663 other proposed reforms, is currently under debate in Congress.

“Big Eggs Like an Ostrich”

The Mexico-based veteran crime journalist Ioan Grillo described the situation in Ecuador as “exceptional,” even by Latin American standards:

Latin American governments like Mexico use the army to fight cartels. But they are largely very wary of calling it an armed conflict. They see this as both bad for their image and legal status. On the ground though many troops treat it like they are fighting an armed conflict. pic.twitter.com/GoEvz6Balx

— Ioan Grillo (@ioangrillo) January 11, 2024

The government’s heavy handed approach is distinctly at odds with Noboa’s electoral campaign pledges regarding security. As Insight Crime notes, Noboahad spoken of working to reduce crime by tackling its socioeconomic causes, as well as training police officers in non-violent conflict resolution and investing in community policing. But that was before the assassination of presidential candidate Fernando Villavicencio, on August 9. His death, along with the murders of other politicians, revived public calls for tougher strategies to combat crime.

But who is Daniel Noboa, apart from being the son of Ecuador’s richest man, Álvaro Noboa, the grandson of one of Ecuador’s richest men, Luis Noboa Naranjo, and the youngest democratically elected prime minister in the country’s history?

Arguably more a product of the US than Ecuador, Daniel Noboa was born and raised in the States, where he obtained graduate degrees from Kennedy School at Harvard University, Kellog School of Management at Northwestern University, and George Washington University. His political party is seven months old and his governing team wet behind the ears, with many ministers younger than 35 and with zero experience of senior government.

Noboa and his team will have to grapple with Ecuador’s worst crisis this century. In the space of just seven years, the country has gone from being one of the safest in Latin America to being the fifth most dangerous in the world. The country is not just a major transit route for the international drugs trade, particularly for cocaine heading to Europe; it also has one of the worst drug epidemics in Latin America.

In bringing the Ecuadorian military onto the streets, Noboa is doubling down on a strategy already tried and tested by his two predecessors, Lenin Moreno and Guillermo Lasso, as well as in Colombia and Mexico, with disastrous results. From Insight Crime (machine translated):

The use of the armed forces in the fight against organised crime has been a controversial tactic of the Lasso government. After the historic peaks in homicides with which Ecuador closed 2022, the president began to request the deployment of the military against criminal groups. In April, shortly after the country’s Public and State Security Council (COSEPE) declared these groups “terrorists,” Lasso signed a decree ordering the army to begin military operations throughout the national territory against “terrorist organisations and individuals.”

Lasso’s Last Act of Treason

By early-2023 Lasso’s government was on the ropes. Lasso himself was facing the possibility of an impeachment trial following a raft of corruption, tax evasion and money laundering allegations. is in the process of withdrawing from political life that almost led to his impeachment. To ward off that threat, he dissolved parliament in May and called new elections in which neither he nor his party would participate. Lasso’s popularity, like that of Peru’s current President Dina Boluarte, had already hit rock bottom (16% in April) and between May and November he effectively ruled Peru by decree.

One of his last acts was to visit Washington in September 2023, where he signed two key agreements. The first allows for the presence of US military ships in Ecuadorian waters; the second directly sets the conditions for the presence of the US military on Ecuadorian soil. Lasso had been calling for the creation of a Plan Ecuador arrangement to combat the rising lawlessness in the country since at least June of 2022. The plan, he said, would be modelled on Plan Colombia, the disastrous US-designed and -delivered drug-eradication program

The signing of the agreement was attended by Republican Representative Dan Crenshaw, who chairs the “Congressional Task Force to Combat Mexican Drug Cartels,” as well as senior officials from the Coast Guard and the Department of Defence. But it was not officially announced by the Department of State and the only US media outlet to cover the story was the Washington Examiner.

The agreement, as we noted at the time, was controversial for a numbers of reasons. First, Ecuador is one of the few countries in the world to have voted in a referendum, in 2009, to close down all US military bases on its territory and force all US soldiers to withdraw. The last US soldier left the country in 2010. Unbeknown to many Ecuadorians, that move was quietly undone by Lasso, a president who came within a whisker of being impeached for, among other things, his alleged collections to the Albanian mafia, which controls the cocaine routes between South America and Europe.

In 2021, almost a third of the cocaine seized by customs authorities in western and central Europe came from Ecuador, double the amount reported in 2018, according to a United Nations study with data from the World Customs Organisation. Much of that was brought in by Albanian gangs.

In other words, the US had signed an agreement to wage war on the drug cartels in Ecuador with a government that appeared to be in league with at least one of the cartels. In April last year, five US congressmen wrote a letter urging the Biden administration to reconsider the US government’s relationship with Ecuador given the Lasso government’s alleged ties to at least one of the major drug cartels. A couple of paragraphs (though the letter itself is well worth a full read):

Ecuador is now in the midst of a political and social crisis that is driven, in large part, by credible allegations of corruption at the highest levels of government. Investigative journalists have uncovered what appears to be a web of corruption that ties key associates of Ecuadorian President Guillermo Lasso to organized crime figures. Furthermore, there is evidence to suggest that one of these individuals – Danilo Carrera – as well as President Lasso himself have been using U.S. jurisdictions to hide assets and avoid taxes, in violation of Ecuadorian law…

Corruption and criminal activity appear to have deeply penetrated Ecuador’s security apparatus, prompting the U.S. ambassador in Quito to denounce the country’s “narco-generals.” The general security situation has plummeted since Lasso took office with the country’s homicide rate nearly doubling.

Predictably, the Biden administration appears to have taken no notice of the letter. Rather than reconsidering relations with Ecuador, it is intensifying them.

Roots of the Crisis: Austerity, Bananas and Dollarisation

Who is to blame for Ecuador’s almost complete breakdown in law and order?

That depends who you ask. For those on the right, it’s Rafael Correa’s government’s general permissiveness with the drugs cartels and alleged ties with the Colombian insurgency group FARC that is at the root cause. And there is probably a certain amount of truth to that. His government encouraged Ecuador’s gang members to hand in their weapons in exchange for amnesty, and Correa himself is now being ridiculed in the right wing press for once comparing the Latin Kings, one of the groups labelled as terrorists, with the Boy Scouts.

For those on the left, including Correa himself, Lenin Moreno, the man who stabbed Correa in the back by handing over Julian Assange to the British police, allegedly in exchange for a $4.2 billion IMF bailout that signalled the recommencement of brutal austerity in Ecuador, and Lasso are the main culprits after having systematically gutted and dismantled the Ecuadorian state, leaving it incapable of performing even the most basic government functions — including maintaining law and order. The numbers more or less speak for themselves.

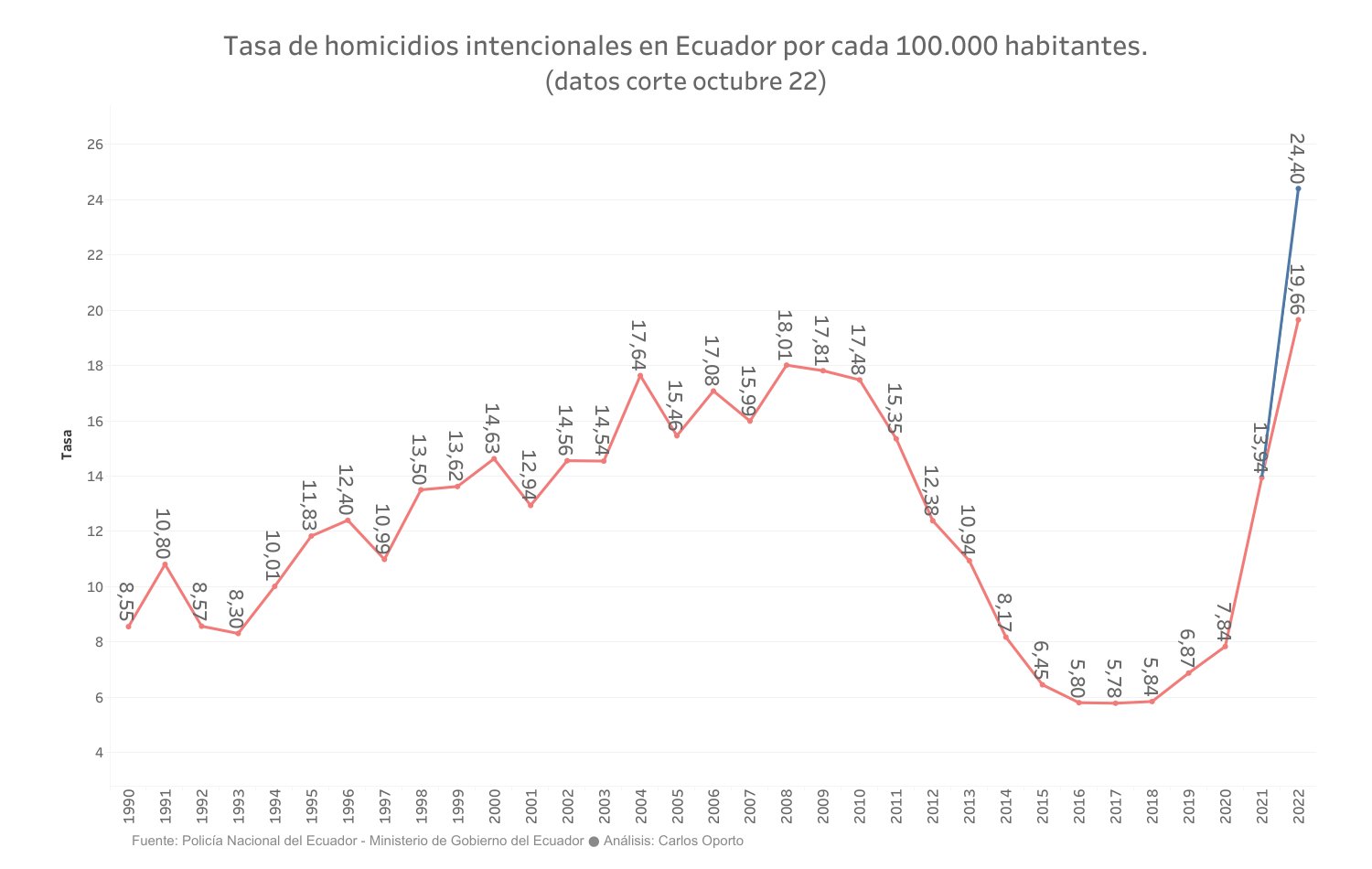

Rafael Correa’s government was in office from 2008 to 2017. Between 2009 and 2017 the homicide rate per 100,000 inhabitants steadily fell from 18 to 5.78, one of the lowest rates in Latin America — a fall of almost 70% in less than 10 years. The Correa government’s law and order reforms even received plaudits from the Washington-based Inter-American Development Bank. The reforms included a significant pay rise for police officers, much closer cooperation between the police and local communities, and increased investment in local policing.

After 2017, the number of homicides began rising once again, first slowly but then rapidly. In 2020, when the Moreno government executed an austerity drive as the economy reeled from the effects of the pandemic and global lockdowns, the rise became exponential. It included budget cuts for police forces. For many people, crime became the only means of survival as firearms were flooding the market, most of them bought or stolen from the police and security forces. Ecuador’s prison system began to collapse after years of under- funding and maladministration. By the end of 2023, the homicide rate had reached 45%, the highest in the region. In just six years, the number of homicides has increased more than seven fold.

In an interview (in Spanish) with Russia Today this week, Correa said:

“I’m an expert in economic development. I have never seen a country self-destruct so quickly in a time of peace, without sanctions or blockades.”*

There are, of course, plenty of other reasons for Ecuador’s dramatic fall from grace beyond (IMF-supported/imposed) austerity. They include bananas and dollarisation, reports the Argentinian journalist Bruno Sgarzini:

Since 2021, money laundering in the country has tripled thanks to dollarization and few banking regulations. Almost the same thing happened with bank profits…

The Mexican Jalisco Nueva Generación and Sinaloa cartels used banana companies as a vehicle to export their drugs. The Albanian mafia, implicated in an investigation of [President Lassa’s] brother-in-law, Danilo Carreras, did the same.

This generated a boom in banana companies involved in the export of cocaine. Of 326 drug seizures in banana cargo in the last five years, the Ecuadorian police found 127 companies responsible.

Exports mostly leave from the port of Guayaquil, one of the most important power centres in Ecuador. Criminal organisations buy banana companies and then use them as fronts for their business, according to authorities.

One of the reasons why they have settled in Ecuador is the few banking regulations and the dollarisation of the economy, which allows money to be laundered more easily. According to the Latin American Strategic Center for Geopolitics (CELAG), during 2021, 3.5 billion dollars was laundered in the Ecuadorian financial system, a three-fold increase on the average $1.2 billion annual haul for the 2007-2016 period.

“The growth of illicit money in the legal stream coincides with the deregulation of the financial system and the extraodrinary profit rates reported by Ecuadorian banks since 2017. CELAG’s findings are in accordance with journalistic investigations that suggest that money laundering accounts for between 2% and 5% of GDP annually,” according to the think tank.

Much of that money ends up in Panama, where, coincidentally, Lasso, who was formerly a senior executive at Banco Guayaquil before entering politics, has a number of offshore accounts.

Insight Crime agrees that dollarisation was the main impetus behind Ecuador’s transformation into a key node in the 21st century drug supply routes. The mass fumigation of coca crops in Colombia, as part of Plan Colombia, and the unlimited ambitions of Mexico’s drug cartels have also played a part (machine translation):

[I]t was not until the beginning of the new century that Colombia’s quiet neighbor emerged as an important link in the transnational cocaine supply chain. It all began with the dollarization of the economy , as a result of the economic and political crisis of the year 2000, which immediately turned Ecuador into the dream of any money launderer: a country on the border with the largest producer of cocaine in the world and that uses the currency of the largest cocaine market in the world.

Around the same time, a military attack and massive aerial fumigation of coca crops in Colombia forced the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) guerrilla and coca growers towards the border with Ecuador. The FARC established control over cocaine production in the region and began supplying traffickers of the Norte del Valle Cartel , who opened routes into and out of Ecuador. It didn’t take long for the Mexicans to want to get in on the action, and the leader of the Sinaloa Cartel, Joaquín Guzmán Loera, alias “El Chapo”, ordered his men to establish their own networks in the country.

* Interestingly, Correa has called for all Ecuadorians to support Noboa’s internal armed conflict with the drug cartels, though he also notes that Noboa’s governing team appears to be making up policy on the hoof.