Yves here. Wolf Richter explains that Treasury yields have clearly been saying that inflation is likely to get worse, particularly in the longer term. In-your-face reminders like egg shortages and Trump tariff actions and threats alone provide grist for these concerns. And recall the 25% tariffs against Mexico were not revoked but merely paused, so they could still go into effect, or be used again for more nerve-rattling Trump shows of force. Wolf depicts the market unhappiness as being with the Fed being too generous with rate cuts too soon, but it’s not hard to see Trump measures as adding to nervousness.

Wolf also points out that the Fed’s mandate is to engineer longer-term yields so as to support groaf. But what does the central bank normally manage? Short term rates. What is its mechanism for managing the longer end of the curve? QE. But that’s become a dirty word due to its use to lower longer term rates to rescue the housing market by reducing mortgage rates. That gave banks some relief and also helped consumers who could refi (and again the banks since they pull a lot of fees out of refis).

By Wolf Richter, editor at Wolf Street. Originally published at Wolf Street

Fed Chair Powell, at his testimony before the Senate Committee on Banking, Housing, and Urban Affairs today, included his nearly standard line about longer-term inflation expectations being “well anchored, as reflected in a broad range of surveys of households, businesses, and forecasters, as well as measures from financial markets.” The first three are survey-based – what households, businesses, and forecasters see coming at them. The last is based on trading results in the Treasury market, what the Treasury market sees coming at it. It’s the bond market talking here, and the bond market is getting worried again about inflation.

The 5-year breakeven inflation rate rose to 2.64% today, the highest since March 2023, having shot up by 78 basis points since just before the Fed’s September rate cut. This measure (5-year Treasury yield minus the 5-year Treasury Inflation Indexed Real Yield) shows what the bond market saw today as the average inflation rate over the next five years.

The Fed has cut by 100 basis points, while this measure of market-based inflation expectations for average inflation over the next five years has shot up by 78 basis points. It has become “unanchored,” as one might say to needle Powell during the FOMC press conference:

A Fed that is lax about inflation scares the bond market once inflation starts rumbling. And the Fed has seen that reaction from the bond market too – including the surge of longer-term yields, such as the 10-year Treasury yield, since the beginning of the rate cuts – which is why it has walked back any talk of further rate cuts and instead has pivoted into wait-and-see mode to not unnerve the bond market further.

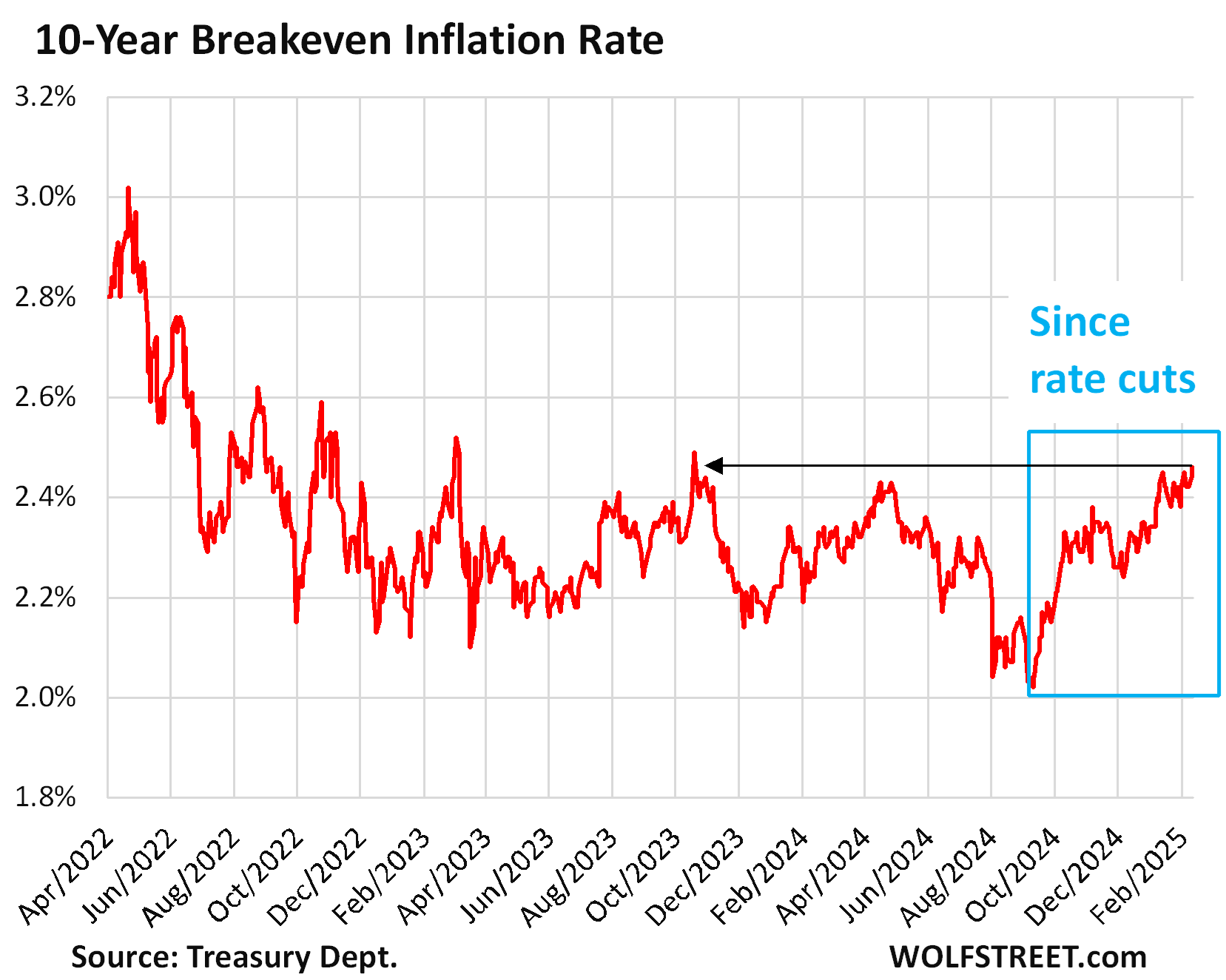

The 10-year breakeven inflation rate (10-year Treasury yield minus the 10-year Treasury Inflation Indexed Real Yield) is a little more sanguine but is also coming unanchored. This measure of what the bond market saw today as the average inflation rate over the next 10 years rose to 2.46%, the highest since October 19, 2023, and before that day the highest since March 2023. It shot up by 44 basis points since just before the Fed’s September rate cut.

The rate cuts unnerved the bond market. The bond market saw that inflation wasn’t quite done with yet when the Fed was cutting rates just as inflation was starting to re-accelerate. This infused the bond market – and not just the bond market – with concerns that the Fed would be more tolerant about inflation going forward, along with signs of fear that inflation would on average be higher over the next five years in particular.

This jump in inflation expectations by the markets, along with the surge of the 10-year yield following the rate cuts, likely triggered the energetic backpedaling by the Fed on further rate cuts. It is now in official wait-and-see mode. Powell and the other Fed governors now keep hammering home the point that they can be “patient” with their rate cuts.

The bias today is still for cuts, not hikes. Inflation would have to make larger and more sustained moves higher for the Fed to switch the bias to rate hikes.

But a bond market freakout over accelerating inflation and a lax Fed – resulting in higher long-term yields that really matter for the economy – would nudge the Fed to switch its bias to rate hikes again. To keep long-term yields from rising too much, the Fed will need to show the bond market that it’s serious about inflation, and that it will crack down again if inflation re-accelerates substantially.

That’s the irony: The Fed might have to hike short-term rates again to make sure long-term interest rates remain “moderate” – paying attention to the third part of its mandate, to conduct monetary policy “so as to promote effectively the goals of maximum employment, stable prices, and moderate long-term interest rates.” The mandate is silent about the Fed’s short-term policy rates. It’s “long-term interest rates” that are in the mandate, and the way to get there is to keep inflation in check.