By Lambert Strether of Corrente.

Readers will recall the previous two posts in what became this series: My Life So Far in Writing Tools, where tools were very analog printed books, like the OED, and My Life So Far in Type, where the type that conveyed the writings was first physical (typewriters), then analog (phototypesetters), and finally digital (the AM Varityper). The transition from analog to digital began at the keyboard and ended up inside the printer, culminating in a workflow that was bits (binary digits) from start to finish (except, of course, for the decimal digits of my hands). At the time, these phase transitions appeared as changes in the flow of my working day, as I hopped from job to job, like Eliza hopping across the Ohio River from ice floe to ice floe (embarassingly, whenever I “reach for” “Eliza” I always grasp Motown’s “Little Eva.” Bad Lambert’s associational memory). In retrospect, I was being borne along on the current of enormous changes, as entire industries dried up, and new industries — from Silicon Valley! — came into full spate.

After several stints as a production manager, still in the printing trades, I ended up in a Boston printshop as a part-time manual paste-up artist, because I felt I wanted to work on my writing. This once again came to nothing — my university friends had long since scattered — but for some reason I ended up at a trade show, where I saw a Macintosh. There were newsstands in those days — racks of printed magazines you could stand and read, without necessarily buying — and Cambridge (down, or up the Red Line from Boston proper) was famous for them. There I perused computer magazines, and noted with interest that there were now computers dedicated to doing whatever it was that the AM varityper did (there was no name for that at this point), but smaller, sleeker, and cheaper. Hmm….

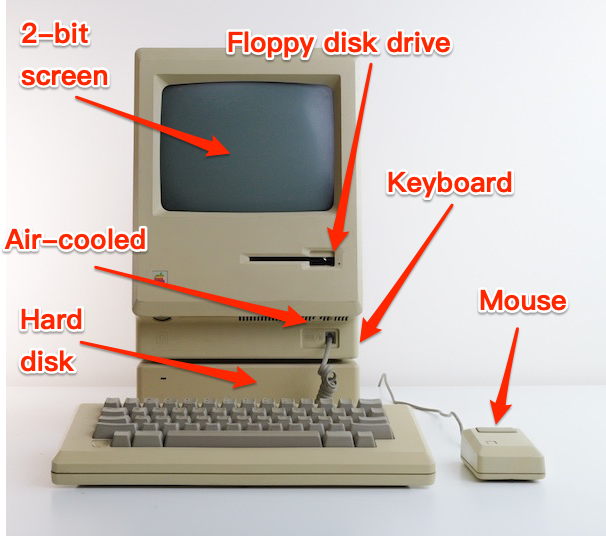

The Apple Macintosh (“Mac”) I saw was a whole new thing, different from the AM Varityper, though having all the same elements: Keyboard, monitor, disk drive, etc. It looked something like this:

There was the rainbow logo, which didn’t look corporate (the wintry whiteout of Apple’s later aesthetic had not yet made its appearance). Moreover, the Mac was clearly designed; the curvaceous yet cute “Hello” reminded my of my family’s friendly and reliable VW bug (and Mac users, for a long time, tended to salute each other in passing, much like VW drivers). For another, it had what I learned were called “applications” — MacPaint, a program that allowed you to draw bits on the screen to make art, was one such, but there was MacWrite, which allowed you to do a thing called “word processing.” Best of all, there were fonts, fonts that came in Roman, bold, italic, and bold italic (all bit maps on the screen, and jagged if you looked too closely). My newsstand reading, however told me that the floppy drive was insufficient to do real work: I discovered that there were actually “tips” — an ecosystem of printed magazines, funded by Apple advertising, was rapidly evolving — on the proper way to hold a new floppy disk so you could insert it rapidly when you ejected the old one. My AM Varityper disk was large, and the drive klunky, but I never had to do that! So I waited….

In the fullness of time, the Mac 512KE — so-called from its 512 kilobytes of RAM (my current Mac has 16 gigabytes) — came onto the market. Being still quite poor, I approached the ‘rents, and they unbelted (generously, considering my difficulties in school, and wisely, since the gift set me on the path to several real careers, including this one). I ended up with a machine that looked a lot like this (with some modifications):

I brought the boxes home to my Somerville apartment under cover of darkness, and set it up on a table I had built. Then I sat on my draftman’s stool and turned it on (“booted it”). Nothing. In fact, for two days nothing. And on the third day, I accidentally jostled the mouse — the AM Varityper had not had a mouse — and the screen sprang to life! I discovered that the machine had a version of Pong, controlled with the mouse, and for two days I did nothing but play Pong. Then I thought “Wait a minute,” stopped, and since then have never played a computer game (on my machine or any other).

As for the naming of the parts: The legendary Steve Jobs apparently hated fans, and so the Mac, like our VW bug, was aircooled. The screen was two bits, one for black, one for white (zero and one in the machine’s RAM). Looked at closely, the entire screen image was an array of black and white dots, and — incredibly! — the dots (I read) were 1/72 of an inch, just like the divisions on my pica ruler. The floppy drive took bigger disks, but I also acquired a hard disk (I forget the brand, but it held an enormous quantity of data: 10 megabytes; enough for half a RAW file these days, but enough for a lot of word processing files, at least. The keyboard was extremely odd after the professional feel of the AM Varityper, and felt odd and klunky — like most Apple keyboards, if truth be known — but at least it wasn’t mushy. And then there was a Doug Engelbart-style mouse (from the tail-like cord, I suppose):

The mechanical mouse has a ball in its underbelly, and as you move the mouse, the ball rolls. Small rollers inside the mouse detect this movement and send signals to your computer, telling it how far and in which direction the mouse is moving. This information is then used to move the cursor on your screen accordingly

All well and good, except the ball (rubber, for this version) picked up whatever it rolled over, and so periodically, when the mouse movements began to hitch and get random, the rubber ball had to be cleaned, which had an enormous ick factor; I still shudder to think of it.

The fonts and the pica-friendliness of the screen led directly to what was called “desktop publishing,” where the Mac did did everything the Typesetting Department, the Art Room, and the Page Makeup Department did, inside the computer, in a single application (and if you already understood type, page geometry, and the language of publications generally, it was extraordinarily easy to become blazingly productive, which I did (thanks again to the generosity and wisdom of my parents; I didn’t need to ask again).

But this post is not about the desktop publishing branch on the path of my so-called career (even though I loved that work just as much as manual paste-up).

This post is about writing.

Having acquired a computer, I joined a computer user group and started going to meetings. The group was entirely run by volunteers (here we recall the recordists of the Macauley Library and correspondents of the OED). One thing volunteers did was write (meeting reports; reviews) and so I volunteered to do that.

My difficulty in writing, whether with pen on paper, or with a typewriter, a sort of rathole blockage. I would start with a fine rush of words, get a few paragraphs and then a few pages in, but I would always encounter a topic where I needed to dig deeper, and then deeper, and the deeper still, and there seemed to be no way to extricate myself from the rathole and go on, and so I stopped. I could never finish anything! I was too young to know about Vladimir Nabokov, who composed on index cards, or P.G. Wodehouse, who wrote on paper sheets, and attached them with clothespins to strings hung from the ceiling. Both techniques permitted re-arrangement, which I needed, but didn’t know that I needed — I blamed myself for unclear thinking — and didn’t even know was possible.

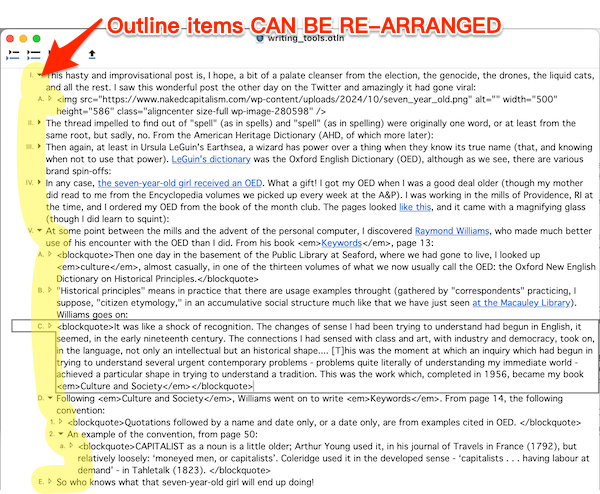

Then I discovered that there was a Mac Desk Accessory (a sort of widget) called Acta[1]. Acta was an outliner, and made outlines just as you were doubtless trained to do in school. Rather than explain what an outline is, I will present part of the outline for the first post in this series, My Life So Far in Writing Tools:

As you can see, the outline items are numbered Harvard-style (I., A., 1., a., and so forth), though I turn off the numbers (except when I want to count paragraphs), because the indentation is enough to show the structure.

The key point: The outline items can be rearranged. I could simply jot down text, in any order, as I pleased, and then polish and re-order until the work was done. That removed the rathole blockage. I could finish! The first time I used Acta, I finished a report. On the same day, I wrote a product review. The feeling was wonderful.

And so, to the extent that writing can be an art, and to the extent I have mastered it, I owe my mastery of the art to the Mac, to the author of Acta, to the digital transformation that brought both into being, and of course to many, many years of turning words into type before that[2]. I can finish!

READER NOTE

My identity is, at this point, pretty porous, now that I’ve gotten somewhat autobiographical. However, I would be grateful, dear readers, if you did not speculate on it in commments, or on the institutions and locations mentioned in these articles. There’s no point making life any easier for Google and than it already is. Thank you!

NOTES

[1] Desk Accessories went away when the Mac OS became Unix-based. The author of Acta, David Dunham, wrote the wonderfully simple Opal outliner, which is no longer maintained (and I dread the day that a so-called upgrade causes my one essential software application to fail). Microsoft essentially killed off the product category by incorporating a brutish and horrid outliner in its Microsoft Word bloatware. (I believe that in this post I am also correcting the record; neither this history of outliners, nor this one, mention Acta or Opal.

[2] Which is one reason I em use a Mac, besides the fact that the user interface and keyboard shortcuts are etched into my muscles, my nerves, and my brain.