PlutoniumKun, who as readers may recall follows Chinese social media and also has a keen interest in development economics, sent a new article by Jonathon P. Sine, a first part in a two-part series on the rise and fall of local government financing vehicles, the shadow banks behind China’s housing bubble. PlutoniumKun describes Sine as “one of the very few western based Chinese commentators who tries to stay above the ideological fray.” PlutoniumKun also reports that this article is garnering very keen interest on Chinese Twitter. That piece is so meaty, and intended to be a reference work, that we will turn to it in a later post.

But before we turn to this deep dive into LGFVs, which as of 2020 had liabilities of roughly 75% of China’s GDP, let’s first turn to Sine’s 2021 must-read piece, Financialization: Is it Worse in the PRC? Readers who have gotten a big dose of Michael Hudson describing how Chinese leadership has steered clear of the Anglopshere traps of neolibearlism and financialization will tend instictively to reject this claim.

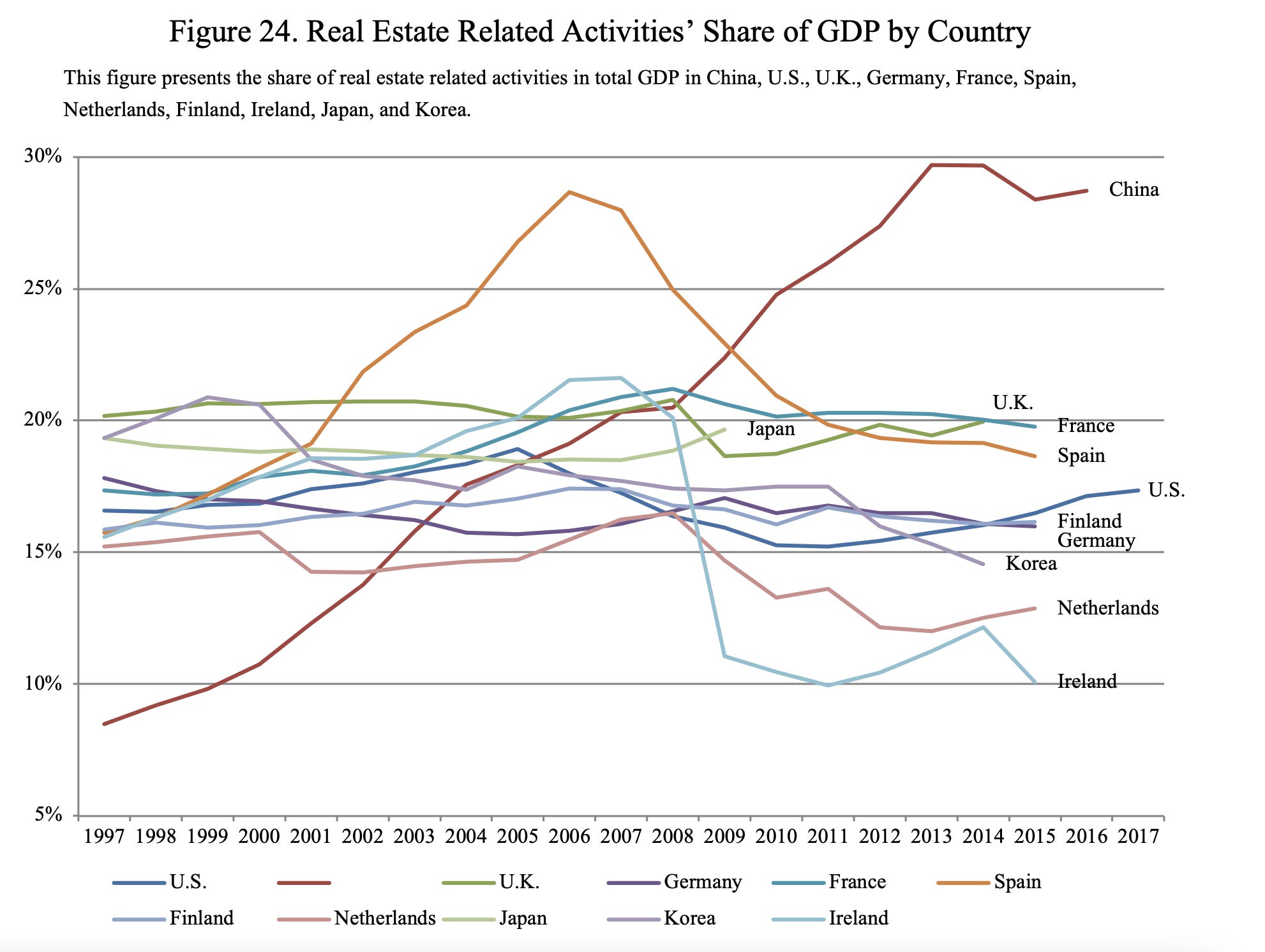

But what Sine presents, and many commentators fail to deliver, is data. Lots of it. From lots of angles. One you’ve read his piece in full, it is hard to dismiss his argument that China is pretty bloody financialized, and even more so on a relative basis than the US.

Skeptics might argue that if Sine is correct, why hasn’t the China-bashing media seized on his thesis? One possibility: depicting financialization, and in particular the level of US financialization, as bad is not something the Western business media is keen to promote. Even if the claims that China is cruising for a bruising include some financial metrics, like declining economic productivity of borrowing (how much incremental debt it now takes to generate a dollar more of GDP), debt levels, debt growth, real-estate related bankruptcies, the doubters tend to focus on the notion that China’s growth rate is flagging or overstated, and contend that that has knock-on effects, particularly making it difficult for China to deliver rising standards of living. They also point out the implications of China’s low birth rate.

And even though Hudson is a critic of financial capitalism, as opposed to industrial capitalism, he’s not alone in that view. None other than the IMF pointed out that financialization, once it passed a not-very-high level, is a negative for growth. From our 2015 post on their study:

Their conclusion was that the growth benefits of financial deepening were positive only up to a certain point, and after that point, increased depth became a drag. But what is most surprising about the IMF paper is that the growth benefit of more complex and extensive banking systems topped out at a comparatively low level of size and sophistication.

The only way to keep a bigger financial system not to act as a drag is via strict regulation, something in absence these days.

Now to turn to the main event. There is so much compelling and carefully argued detail that it’s hard to know which bits to showcase. And I do strongly urge you to read it in full.

Sine starts with the attention-getter that China’s FIRE (finance, insurance, and real estate) sector was already a bigger proportion of GDP than that of the US as of the mid-teeens: 8.5% in the US in 2017 versus 9% in China in 2015, per the deputy director of the Finance and Economics Committee of the National People’s Congress. The official, Yin Zhongqing, recognized this was not a desirable development:

…with the fast expansion of the money supply, vast volumes of funds have cycled back into the financial system, vast amounts of liquidity have never entered the real economy…and ‘casting off the real for the empty’ [脱实向虚] has grown more intense.

This sounds an awful lot like the massive capital flows in Japan that Western bankers swooned over in the mid-later 1980s, and the 2006-2007 “wall of liquidity”. And he invokes that image:

Retirement savings collected from households by institutional investors (such as pension funds and other SPVs), trade surpluses and sovereign funds), surplus money resulting from recent quantitative easing policies and the rise in accumulated profits of transnational companies in tax havens have all created a wall of money that gradually pushed for the financialization of built environment.

In China, FIRE is nearly all real estate; even seemingly normal manufacturing companies are very often heavily involved in development projects (and not as builders). In a rare sour note, Sine depicts the driver as a savings glut, when that line of thinking comes out of the bogus loanable funds model, that loans come out of savings. In fact, it’s the reverse: banks lend out of thin air, creating deposits. So what Sine is really saying is there is more lending than productive outlets. That is also what we saw in Japan in the mid-1980s, when among other things, companies could (and did) borrow 100% of the fictive value of urban land (fictive because it virtually never traded; selling land was regarded as akin to selling your children, an admission of bankruptcy). Similarly, as we explained long form in ECONNED, the pre-global-financial-crisis wall of liquidity resulted from the massive gearing of heavily-synthetic subprime CDOs.

This schematic shows how it works:

China has a savings rate of 50%, highest in the G-20, and mainly from households and non-financial companies. This lends some support to the complaint that China does not consume enough. Economic activity is sending more income and revenues to workers and their employers, but they aren’t plowing it back into the system by buying things, but by investing/speculating in real estate to an excessive degree.

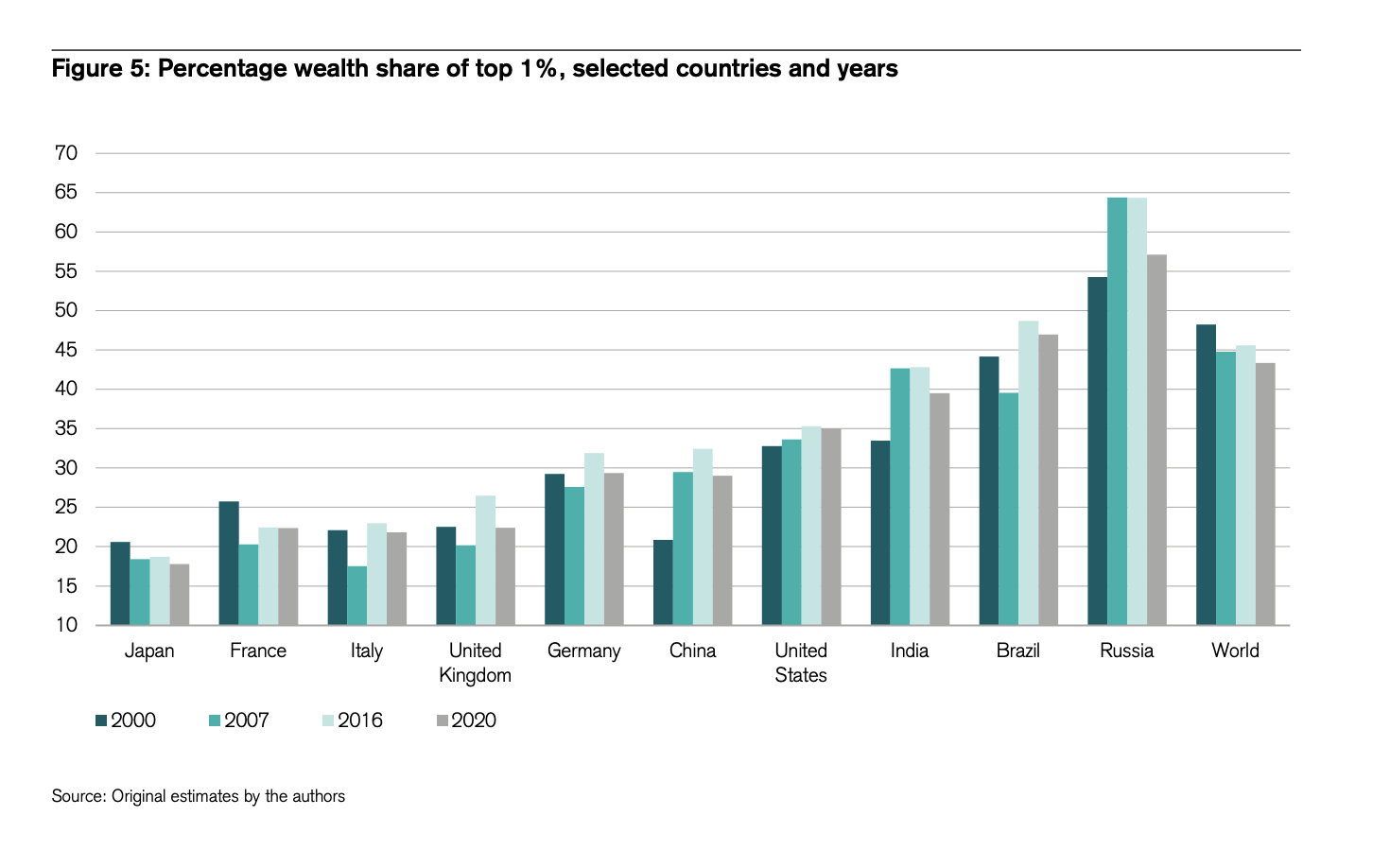

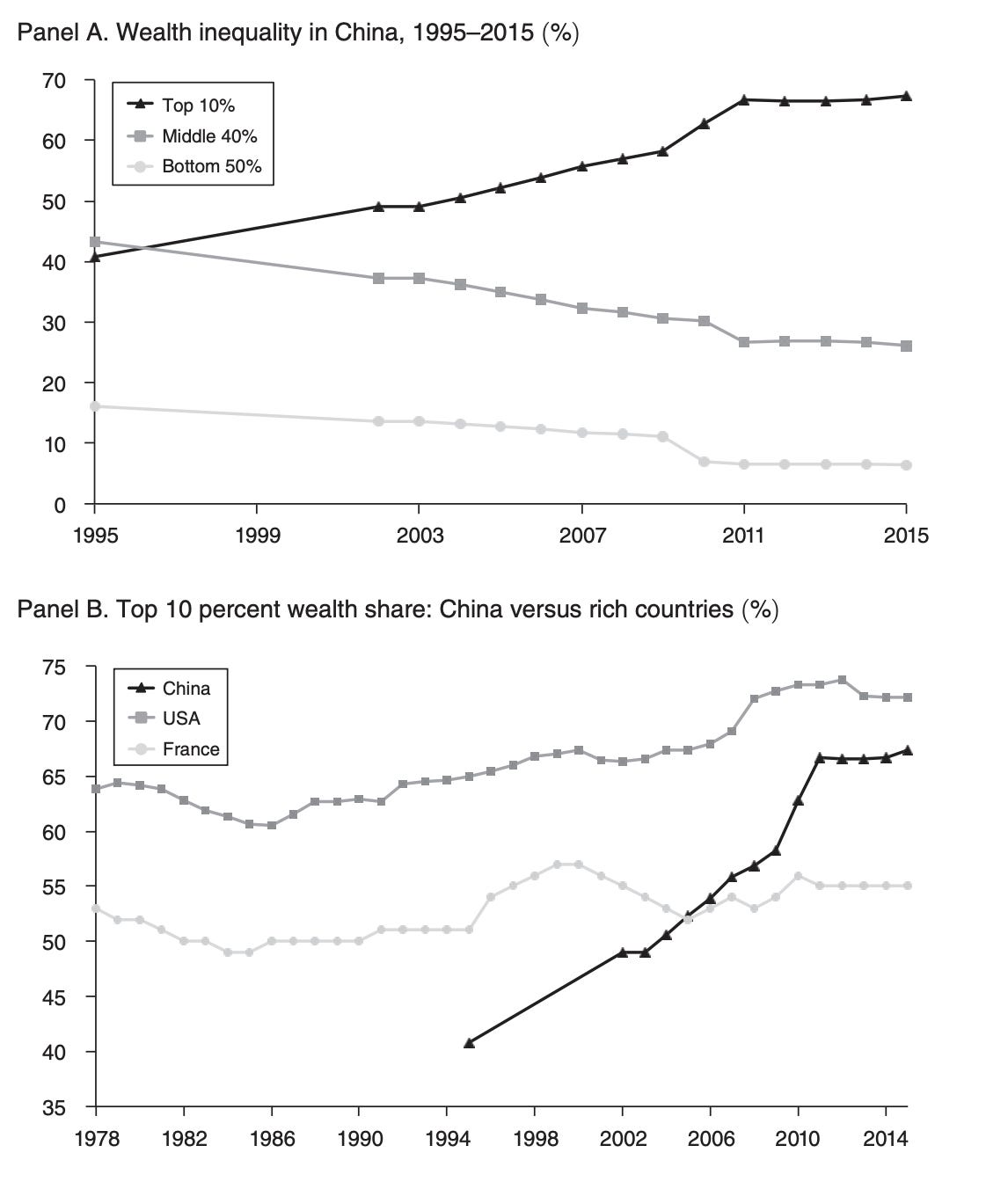

Another sign of financialization is the rise in wealth disparity, with China approaching US levels”

Additional measures:

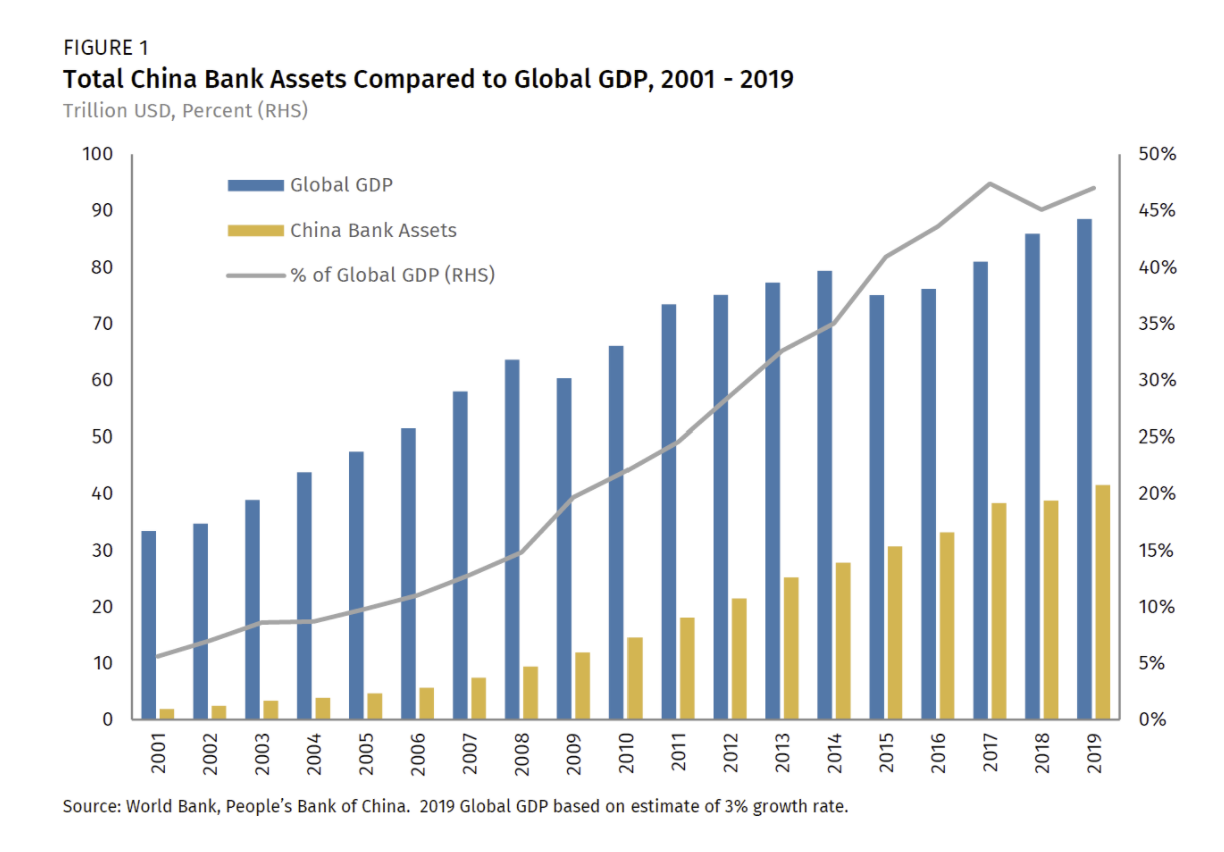

Sine then turns to loan and financial system growth, which if you were of the “loans create deposits” school of thought, you’d put first:

Logan Wright and Daniel Rosen have written extensively on the topic, and in a recent note in 2020 try to frame the stunning numbers in a comprehensible fashion. The PRC’s financial system

“has increased in size by 4.5 times since the global financial crisis, rising from 64.2 trillion yuan ($9.4 trillion) in assets as of the end of 2008 to 292.5 trillion yuan as of last month ($41.8 trillion). To put the current value in context, it represents about half of global GDP. In the same interval, China’s GDP roughly tripled in size, adding around $9 trillion in annual output.”

Here is the phenomena in graphic form:

The US banking system is $21 trillion. So, in terms of raw financial system size, that problem is worse in China.

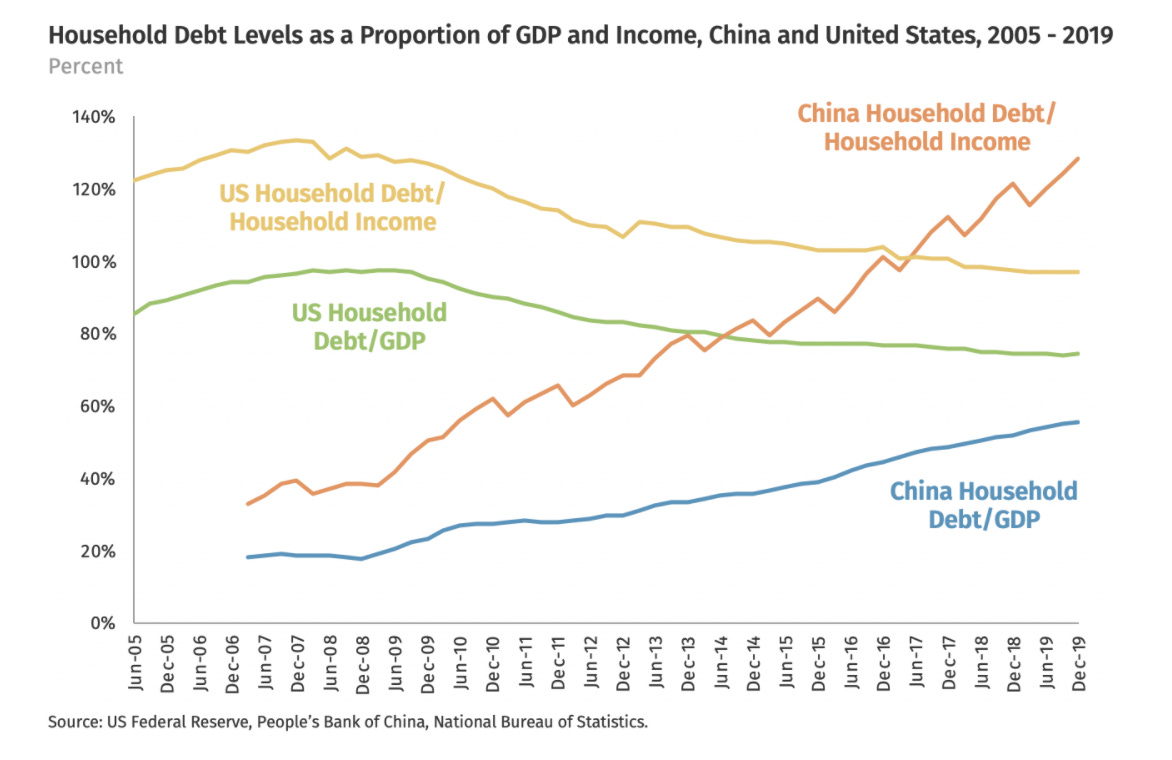

Household borrowing is also very high for a country that is only at best on the cusp of being an advanced economy:

Remember, China does not have America’s student debt overhang or much use of credit cards and therefore presumably only pretty trivial credit card debt. But apps hand out microloans like candy and young borrowers reportedly fall prey to them. They do finance car purchases, but not as frequently as in the US.

But all the household dough is going overwhelmingly to real estate, with it accounting for 80% of typical net worth, versus 35% in the US. That much money going into property has unbalanced the entire economy:

There’s even more evidence in this post, but the extended recap above will hopefully prove to be persuasive. We’ll stop here and again suggest you read it in its entirety.

And yes, the update via Sine’s deep dive into local government financial vehicles only adds more grist to this view. We hope to turn to that tomorrow.