Getty Images

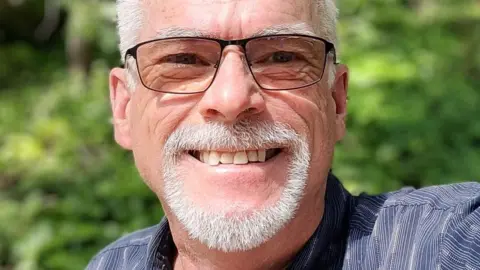

Getty ImagesRick Pero was working in southern Mexico when the evacuation alerts started going off on his phone.

A wildfire was threatening his California neighbourhood. Again.

Back home – roughly 2,800 miles (4,500km) away – a man at a popular swimming hole shoved a burning car down into a dry, grassy ravine. Almost instantly, the area ignited and those enjoying the summer day started to panic. The flames, about 15 miles (24km) from Mr Pero’s home, were spreading fast in the tinder dry brush.

“Uh oh, this is not looking good,” Mr Pero thought as he watched the blaze’s growth from his phone.

Within hours, the Park Fire had consumed more than 6,000 acres and residents in the area were forced to evacuate. With them, the suspected arsonist who police say blended into the worried crowd and fled the area.

Mr Pero, glued to his phone, packed his bags. He told his cat sitter to get his two felines and leave before it was too late. He knew the danger after surviving the deadliest and most destructive wildfire in California’s history in 2018 – which razed the town of Paradise and took 85 lives. His home was incinerated.

Mr Pero rebuilt his life in Forest Ranch, another small community about nine miles (14km) north of Paradise. He thought he was safe – his new “silver lining” home had stunning views and was much more fire resistant. But once again, a fire tore through his home and everything inside of it – possibly also stealing one of his cats that couldn’t be lured out of the house.

The metal disfigured shells of two vehicles remain where his garage once stood. Charred metal debris lay in piles. The foundations of the home aren’t even apparent anymore but some bricks from what appears to be a fireplace are stacked. The colourful sunset views over the wooded area behind his home now looks out on hundreds of scorched – and still smoking – pine trees.

“The big sadness is we have a very close-knit neighbourhood,” he said. “I’m again, so, so grateful that they were able to save all of my neighbours, almost all my neighbours, houses.”

Wildfires are becoming more intense and more frequent.

The Park Fire, which started 24 July in a park in Chico, grew to more than 71,000 acres in just 24 hours. It’s now the fourth largest wildfire in California history after tearing through more than 400,000 acres and like Paradise, it spread at a shockingly fast and hot pace.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesAbout 12 hours after the blaze started, the person authorities say is responsible was arrested. Police say Ronnie Dean Stout II was spotted starting the fire and blending into the crowd as people rushed to flee. Witnesses said he acted erratically and may have been intoxicated.

Authorities found him at a nearby mobile home park and charged him with arson. He has not entered a plea but reportedly told authorities his burning car rolled down the 60-foot embankment and it was an accident. He fled the area afterwards because he was afraid, Butte County District Attorney Michael Ramsey said.

The blaze has consumed land in four counties, scorching an area larger than the size of greater Los Angeles or London. Although most of the land is uninhabited by humans, hundreds of homes have been lost in the blaze and experts worry it could take months before it’s fully extinguished.

The area is a frequent target of destructive wildfires. The region in northern California “has had four of the largest 10 fires” in the state’s history, Cal Fire Incident Commander Billy See said at a news conference

Eight of the 10 largest wildfires in California history have happened in the last five years. Scientists say the impacts from wildfires and other extreme weather events have worsened due to climate change. And undoubtedly, this new fire will reinvigorate debates about where and how we live and rebuild in an increasingly hot and dry Western United States.

Escape from Paradise

Last time he evacuated, in 2018, Mr Pero was home with his wife in Paradise. They had just 20 minutes to flee – but it was enough time to grab their photo albums, phones, computers, cars and cats.

That fire ripped through Paradise at a truly unprecedented speed and heat – catching everyone off guard with its ferocity. Of the 85 people who perished, many died in their cars, trying to escape on the rural town’s windy, mountain roads.

Paradise Police Sgt Rob Nichols was one of the many quick-thinking heroes that day. As fire engulfed the town, propane tanks exploded and power lines and burned-out cars blocked the road. His wife and young children got out safely, but Sgt Nichols stayed to help.

Along with firefighters and volunteers, they smashed the windows of an empty building that had a large parking lot – a barrier that could prevent the building from burning – and hustled about 200 people inside as they watched in horror as their beloved mountain town burned. Sgt Nichols lost everything he owned.

He still works in Paradise but he resettled with his family in Chico, about a mile from where the Park Fire ignited. Chico was where many of the Paradise evacuees headed in 2018 – many sleeping in tents around a Walmart or in camper vans until they could resettle elsewhere.

Sgt Nichols was on vacation – 135 miles (217km) away in Lake Siskiyou – when he started hearing news that a wildfire was threatening his home. Again.

“On our last evening up there, we couldn’t rest not knowing what was going on and how close it was to the home,” he said. “So we came home.”

Sgt Nichols didn’t anticipate how scary it would be for his children, ages 12 and 13, as they arrived home and saw flames taking over an area on the ridge above their neighbourhood.

“That was kind of a big trigger for them,” he said.

Fortunately, their house was spared. The wind sent the blaze in the opposite direction.

But it was close. He sometimes thinks about moving to a less fire prone area.

“My wife has a lot of family here,” he said, noting the ties that have kept them in the area. “And, you know, we lost seven homes. Her family lost seven homes in the Camp Fire. And so we don’t want to go too far.”

Paradise is likely safer now than most places, he argues, because there just isn’t much left to burn. He’d like to rebuild there, but building costs have skyrocketed and insurance is prohibitively expensive due to wildfires.

Now Sgt Nichols is patrolling around Chico – on loan from Paradise police – to help deter looters or opportunists who attempt to raid communities after an evacuation order.

Fire resistant

Mr Pero saw his Forest Ranch house as a paradise away from Paradise because of its natural beauty and how close it kept him and his wife to the community they’d grown to love.

He became serious, maybe obsessed, about fire safety and was in charge of his neighbourhood’s fire mitigation. He says it’s “ironic” his home burned. He had about 50 yards of cleared space behind his house, a barrier he hoped would stop any potential blaze from continuing toward his oasis.

“It had 60,000-gallon water tanks. It also had fire hydrants on the street,” he said. “And the big part, it was also about a one-minute route to get evacuated out on Highway 32 versus nine hours in Paradise.”

Every year, they brought in hundreds of goats to clear brush, which can be like kindling for any fire, throughout the community. He urged his neighbours to make their homes fire safe by trimming trees and clearing brush.

He’s hoping his lost cat – a striped grey and black feline named CatMandu – made it out alive. Mr Pero has been leaving out food and searching for him around the wreckage.

But the charred remains of his home are still too toxic to walk around – he needs a special mask and suit to search for any sign of the cat or any belongings that survived the blaze.

“I tried to look from the edges,” he said. “Didn’t see anything.”

Three other homes on his street also burned to the ground. They were owned by Paradise fire survivors, he says.

He and his wife loved their time in Forest Ranch. But he doubts they will rebuild there. He says he doesn’t know if they can start over again in such a fire-prone area. They’re thinking maybe somewhere coastal – near water. Somewhere less dry. Somewhere safer.

He knows people who have relocated to the rain-prone state of Oregon and the often-rainy Ireland.

“We’re kind of wide open now.”