The Issue:

One outcome of the COVID-19 pandemic was a significant rise in house prices. Prices rose by 13.5% from March 2020 to March 2021 and by an additional 20.6% from March 2021 to March 2022, as measured by the Case-Shiller U.S. national house price index. This has intensified the focus on the lack of affordable housing in the United States.

While there are numerous factors driving the rise in house prices, the increasing scarcity of housing units has risen to the top. This problem has been building (or not, as the case maybe) for decades. But the pandemic took it to a whole new level.

Rex Nutting: Home prices have risen 100 times faster than usual during the COVID-19 pandemic

The U.S. has been building fewer housing units relative to the number of households over the past three decades than historical trends.

Econofact.org

The Facts:

The United States faces a housing stock gap. While estimates of the shortfall vary, analysts agree that the available supply of housing in the United States has not been large enough to adequately meet existing demand. An analysis from Freddie Mac, for instance, estimated the housing stock gap to be 3.8 million units in 2020, up from 2.5 million units in 2018.

We have been building fewer units relative to the number of households over the past three decades than historical trends. The annualized number of housing starts per 1,000 households was 22.2 between 1960 and 1990, but it dropped to 12.2 housing starts per 1,000 households between 1990 and April 2022 (see chart). It is important to note that this drop predates the significant decline in housing starts during the Great Recession.

A key to understanding this housing supply shortage is the role of local zoning and land-use restrictions. Having ceded the control of zoning to local jurisdictions has meant that homeowners have been able to persuade their local officials to restrict the supply of housing.

This is particularly the case for the construction of lower-priced starter homes and multifamily housing in U.S. suburbs. The prevalence of this so-called “NIMBY (Not in My Backyard)” syndrome has led to a large increase in restrictive zoning that has limited the construction of new housing and raised prices.

For instance, the share of jurisdictions that limited the maximum number of dwelling units allowed in the highest residential zone to less than 8 per acre rose from 15.5% in 1994 to 16.0% in 2003 and to 22.4% in 2019 based on data from the National Longitudinal Land Use Survey (1994, 2003, 2019), for jurisdictions that responded to all three surveys.

Two land-use regulations have had a particularly significant effect on reducing the supply of housing: minimum lot-size restrictions and single-family-only zoning. If the minimum lot-size restriction (MLR) is one acre, then any new construction must be on a lot size of at least an acre. In research with Maurice Dalton, we find that increasing the size of the minimum lot required led to a large and significant rise in house prices using data for the Greater Boston Area.

The fact that single-family-only zoning has also limited housing supply has only recently become apparent and this has led cities like Minneapolis and states such as Oregon and California to prohibit single-family-only zoning.

There are other constraints on new housing supply that have been exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic and will take some time to resolve. New construction has been hampered by a shortage of construction workers.

The tightness in the supply of construction workers is illustrated by a significant rise in construction-sector job openings: Monthly construction sector job openings have risen from a low of 24,000 in 2009 to 434,000 in May 2022 (see here). And a 2020 survey by the Associated General Contractors of America found that 81% of construction firms reported having trouble filling positions, and 72% anticipated labor shortages to be the biggest hurdle in the next year.

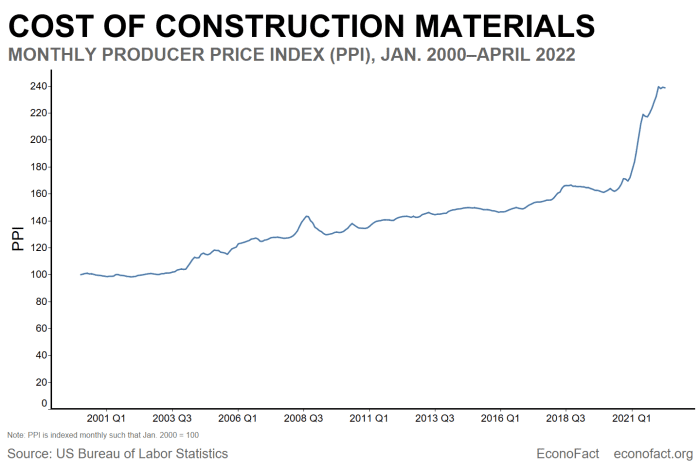

In addition to the worker shortage, there has been a dramatic rise in the cost of building materials since the beginning of the COVID-19 Pandemic (see chart below). It is very likely that the worker shortage will take longer to fix than the high materials costs. But the scarcity of workers and the high cost of inputs could already be putting a dent in construction: privately owned housing starts in May were 14.4% below the number in April.

Econofact.org

Are large-investor purchases also driving the rise in housing prices? The share of home purchases represented by large investors has been rising and reached a peak of 28% of all single-family homes purchased in February 2022. There is a view that these investors have squeezed out first-time home buyers through their purchases and by raising house prices.

The increase in large-investor purchases comes from investors who then rent out the units versus flip them, which is the focus of these concerns. However, the percent of first-time home buyers among all home buyers was 34% in 2021 and it has been at or close to this level since 2014 (it was around 40% prior to the Great Recession). There is no evidence (yet) that this recent rise in large investor purchases has increased house prices (it could be that the increase in large investors is a reaction to the large price increases versus the reverse).

And on a positive note, there is evidence that the increase in large investors helped support the recovery after the Great Recession through the purchase of real estate owned (REO) properties in distressed local housing markets (see here and here).

How the recent sharp rise in mortgage interest rates will impact the supply of housing is unclear. As the Federal Reserve began a series of increases in the discount rate in its efforts to rein in inflation, mortgage interest rates have seen one of the fastest increases in decades: the average 30-year fixed-rate mortgage went from 3.2% at the beginning of 2022 to 5.8% in mid-June. This is primarily a demand-side issue as it increases the cost of borrowing. The drop in demand from higher mortgage rates should reduce future house-price growth rate increases. But rental rates have also been rising so the alternative of renting versus owning (for first-time home buyers) is not great. How this will affect the supply side of the housing market is unclear.

What This Means:

In May, the Biden-Harris administration announced the housing supply action plan to address this housing shortage. The Biden-Harris plan includes policies to address restrictive zoning and provide additional financing for the construction of affordable housing. It proposes partnering with the private sector to address supply-chain disruptions for building materials, promoting manufactured housing and construction R&D, and recruiting more workers into good-paying construction jobs.

The plan also involves addressing the rise of large investors by taking steps to direct the purchase of houses to owner-occupants and nonprofits instead of large investors, but it is not clear how this would be achieved. The administration plan claims that the housing supply gap is 1.5 million units, well below the estimate of 3.8 million units from Freddie Mac and that its plan will close the housing supply gap in five years.

While the plan is comprehensive, it will likely take much longer to fully resolve our housing shortage, particularly since many of the programs the administration is pushing must go through Congress and almost all will take years to begin to show any significant results.

Jeffrey Zabel is a professor of economics at Tufts University. His research interests include housing economics, the valuation of environmental goods, the economics of brownfields, the economics of education, and welfare analysis.

More on housing

Jeffrey Zabel: Where are house prices rising the most? And why are they going up so fast?

Aarthi Swaminathan: Americans are growing ‘increasingly frustrated’ with the economy and gloomy about the housing market, Fannie Mae survey says

Katie Marriner: Here’s how much housing inventory has risen with higher rates. Our interactive map can help you track the number of homes available for sale near you.